7.4. Formal Organizations

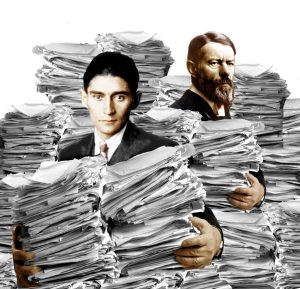

A complaint of modern life is that society is dominated by large and impersonal secondary organizations. The individual gets lost in the paper work and digital files through which modern society is administered. From universities to businesses to health care to government, these organizations are referred to as formal organizations.

A formal organization is a large secondary group deliberately organized to achieve its goals efficiently and effectively. Typically, formal organizations are highly bureaucratized. The term bureaucracy refers to what Max Weber termed “an ideal type” of formal organization (1922/1946). In its sociological usage, “ideal type” does not mean “best,” “good” or “perfect”; it refers to a general or typical model that can be used to describe a collection of characteristics, or a model that could describe most examples of the item under discussion.

For example, if a professor were to tell the class to picture a car in their minds, most students will picture a car that shares a set of characteristics: four wheels, a windshield, and so on. Everyone’s car will be somewhat different, however. Some might picture a two-door sports car while others might picture an SUV. Some might picture an electric car while others might picture a combustion car. It is possible for a car to have three wheels instead of four. However, the general idea of the car that everyone shares is the ideal type.

Corporate, state and other organizational bureaucracies are similar. While each bureaucracy has its own idiosyncratic features, the way each is deliberately organized to achieve its goals efficiently shares a certain consistency. In this sense bureaucracies are defined by an ideal type common to most large scale modern organizations.

Types of Formal Organizations

|

|

Sociologist Amitai Etzioni (1975) posited that formal organizations fall into three categories. Normative organizations, also called voluntary organizations, are based on shared interests. As the name suggests, joining them is voluntary and typically people join because they find membership rewarding intrinsically, or in an intangible way. Compliance to the group is maintained through compliance with shared norms or moral control. The Audubon Society or a ski club are examples of normative organizations.

Coercive organizations are groups that one must be coerced, or pushed, to join. These may include prison, the military, or a rehabilitation centre. Compliance is maintained through force and coercion. Goffman (1961) states that most coercive organizations are total institutions (see Chapter 5. Socialization). A total institution is one in which members are separated from the rest of society and live a fully controlled life to submit to a process of total resocialization.

The third type are utilitarian organizations, which, as the name suggests, are joined for instrumental purposes, as a means to an end. People enter them to pursue a specific credential or material reward. A high school or a workplace would fall into this category — one is joined in pursuit of a diploma, the other in order to make money. Compliance is maintained through remuneration and rewards.

As a result of these differences, the feelings of connectedness between members differs, from shared affinity and common interests in normative organizations, to coerced affinity and disciplinary confinement in coercive organizations, to pragmatic affinity or shared goals in utilitarian organizations.

| Normative or Voluntary | Coercive | Utilitarian | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benefit of Membership | Non-material benefit | Corrective or disciplinary benefit | Material benefit |

| Type of Membership | Volunteer basis | Obligatory basis | Contractual basis |

| Feeling of Connectedness | Shared affinity | Coerced affinity | Pragmatic affinity |

Bureaucracies

Bureaucracies can be described as an ideal type of formal organization. As noted above, this does not mean that they are perfect, or “ideal” in an ethical sense, but that the logic or relationship of their components can be laid out according to an idealized model. Not all formal organizations or bureaucracies will necessarily conform to the ideal type.

The sociologist Max Weber (1946 (1922)) influentially characterized the bureaucratic ideal type on the basis of five distinct features: hierarchy of authority, clear division of labour, explicit rules, impersonality and meritocracy. These were elements of the modern, rational, continuous, methodical, and disciplined organization known as bureaucracy — literally “rule by desks” or “rule by offices” — which proved superior in efficiency and effectiveness to previous, historical organizational forms. As he put it, bureaucracy ws discipline’s “most rational offspring” (Weber, 1946 (1922)).

Previously, rule was often personalized and rulers worked through “personal trustees, table companions, or court servants” on an ad hoc (as needed) basis rather than on a permanent basis. Bureaucracies introduced permanent organizational structures with fixed jurisdictions.

Yet even though Weber argued that bureaucracy had become a permanent structure in modern organizational life because of its rational organization and efficiency, people, both then and today, often complain about bureaucracies, declaring them to be slow, rule-bound, difficult to navigate, and unfriendly. Nevertheless, he argued that “the decisive reason for the advance of bureaucratic organization has always been its purely technical superiority over any other form of organization.” This formidable efficiency in turn means that bureaucracy is “a form of power relation…that is practically unshatterable” (Weber, 1946 (1922)). It is very difficult to imagine another form of social organization up to the task of ruling and coordinating activities on a large scale in modern complex societies. Are other alternatives to formal bureaucracy possible?

As Weber observed, the strength of bureaucratic discipline was that when an order was given it would be methodically executed by well trained functionaries regardless of their personal feelings on the matter. This was enabled by the five features of bureaucracy.

Hierarchy of authority refers to the aspect of bureaucracy that places one individual or office in charge of another, who in turn must answer to their own superiors. For example, if an employee at Walmart gets their tasks assigned by their shift manager. The shift manager answers to the store manager, who must answer to the regional manager, and so on in a clear, unambiguous chain of command up to the CEO, who must answer to the board members, who in turn answer to the stockholders. There is a clear chain of authority that enables each person to know who they are answerable to or responsible for, which is necessary for the organization to make and comply with decisions.

A clear division of labour refers to the fact that within a bureaucracy, each individual has a specialized task to perform. There are specified spheres of competence and responsibility within a systematic division of labour. For example, psychology professors teach psychology, but they do not attempt to provide students with financial aid forms. In this case, it is a clear and commonsensical division. But what about in a restaurant where food is backed up in the kitchen and a host is standing nearby texting on her phone? The host’s job is to seat customers, not to deliver food. Is this a commonsensical division of labour?

There is a continuous organization of official functions bound by explicit rules. Rules are explicitly stated, written down, and standardized. There is also written documentation of administrative acts, decisions, meetings and procedures so that a detailed institutional memory can be kept. For example, at a college or university, student guidelines governing numerous aspects of student life from class attendance, to illness, exam procedures and plagiarism are contained within the student calendar. Similarly, Ombudsperson Offices are becoming more common on campuses to deal violations of rules about racism, sexism, unfair treatment, and student rights. These processes of adjudicating fairness issues involve following explicit procedures of documentation, mediation and correction.

Bureaucracies are also characterized by impersonality, which is meant to take personal feelings out of professional situations and make the institution and institutional processes independent of particular functionaries and clients. Each office or position exists independently of its incumbent, meaning that positions are defined and continue through time regardless of the person occupying them. The business of the bureaucracy is also conducted impersonally, “without regard for persons” (Weber, 1946 (1922)). Each client and each worker receive equal treatment, regardless of who they are, their personal background, or their personal circumstances. This characteristic grew out of a desire to eliminate the potential for nepotism, discrimination, backroom deals, and other types of “irrational” favouritism. Impersonality is an attempt by large formal organizations to protect their members, clients and customers. However, the result is often that personal experience is disregarded. For example, a worker may be late for work because her car broke down, but the manager at Pizza Hut does not care why the worker is late, only that she is late. The rules apply whatever the specific circumstances.

Finally, bureaucracies are in principle meritocracies, meaning that hiring and promotion are based on proven and documented skills, rather than on nepotism, discrimination or random choice. In order to get into graduate school, one needs to have an impressive transcript. In order to become a lawyer and represent clients,one must graduate from law school and pass the provincial bar exam. These are documented credentials that can be weighed and compared in job or student competitions. Of course, there is a popular image of bureaucracies that they reward conformity and sycophancy rather than skill or merit. “One rises to one’s own level of incompetence.” How well do established meritocracies identify real talent though? Wealthy families hire tutors, interview coaches, test-prep services, and consultants to help their children get into the best schools. This starts as early as kindergarten in New York City, where competition for the most highly regarded schools is especially fierce. Are these schools, many of which have copious scholarship funds that are intended to make the school more democratic, really offering all applicants a fair shake?

Max Weber (1946 (1922)) summarizes the principle of bureaucracy:

Precision, speed, unambiguity, knowledge of the files, continuity, discretion, unity, strict subordination, reduction of friction and of material and personal costs — these are raised to the optimum point in the strictly bureaucratic administration … Bureaucratization offers above all the optimum possibility for carrying through the principle of specializing administrative functions according to purely objective considerations . . . The ‘objective’ discharge of business primarily means a discharge of business according to calculable rules and ‘without regard for persons.’

There are several positive aspects of bureaucracies. They are intended to improve efficiency, ensure equal opportunities, and increase effective delivery of services or products. There are times and circumstances when rigid hierarchies are needed. However, there is also a clear component of irrationality within the rational organization of bureaucracies. As a byproduct of rational organization, bureaucracies can be inefficient and ineffective in a number of ways.

Firstly, bureaucracies create conditions of bureaucratic alienation in which workers cannot find meaning in the repetitive, standardized nature of the tasks they are obliged to perform. As Max Weber put it, the “individual bureaucrat cannot squirm out of the apparatus in which he is harnessed… He is only a single cog in an ever‐moving mechanism which prescribes to him an essentially fixed route of march” (1946 (1922)). Secondly, bureaucratic procedures can lead to inefficiency and ritualism (red tape). They can focus on rule following and regulations to the point of undermining the organization’s goals and purpose. Thirdly, bureaucracies have a tendency toward inertia. Changing the direction of a bureaucratic organization in response to new goals, situations and circumstances can be like “trying to turn a tanker around mid-ocean.” Something large, cumbersome and set in its ways has difficulty changing directions. Inertia means bureaucracies focus on perpetuating themselves rather than responding to new needs or effectively accomplishing the tasks they were designed to achieve. Finally, as Robert Michels (1949 (1911)) argued, bureaucracies are characterized by the iron law of oligarchy in which the organization is ruled by a few elites. The organization serves to promote the self-interest of oligarchs and insulate them from worker input or the needs of the public or clients.

Bureaucracies grew large at the same time that modern institutions like the public school system, the industrial workplace, the hospital system and modern armies were developed. In the Fordist economic model of the first half of the 20th century, young workers were trained and organizations were built for mass production, assembly-line work, and factory jobs. In these scenarios, a clear chain of command was critical because of the large scale and centralized nature of production and the number of moving parts that needed coordinating. Now, in post-industrial, late capitalist societies, this kind of rigid training and adherence to protocol can actually decrease both productivity and efficiency.

Today’s workplace is based on flexible accumulation and just-in-time inventory systems (see Chapter 4. Society and Modern Life), which are argued to require a faster pace, more distributed problem solving, and a flexible approach to work. Smaller organizations are often more innovative and competitive because they have flatter hierarchies and more democratic decision making, which invites more communication, greater networking, and increased individual participation of members. These flexible systems are often based on precarious and uncertain work conditions, but too much adherence to hierarchical chains of command, inflexible rules and a division of labour can leave an organization behind. However, once established, bureaucratic structures can take on a life of their own. As Max Weber said, “Once it is established, bureaucracy is among those social structures which are the hardest to destroy” (1946 (1922)).

The McDonaldization of Society

The McDonaldization of society refers to the increasing presence of the fast-food business model in common social institutions (Ritzer, 2013). This business model is based on four principles: efficiency, predictability, calculability, and control (monitoring). For example, in the average chain grocery store every aspect of the organization is geared toward the minimization of time it takes for a customer to shop, for shelves to be restocked, and for checkout and payment to be made (efficiency). Whenever a person enters a store within that grocery chain, they receive the same type of goods, see the same floor organization, and find the same brands at the same prices (predictability). Prices are clearly marked and goods sold by the kilogram, so that customers can weigh their fruit and vegetable purchases rather than simply guessing at the price for that bag of onions. Employees often have a time card so their hours, work process, breaks and wages can be precisely quantified, measured and standardized (calculability). Finally, customers will notice that all store employees are wearing a uniform (and usually a name tag) so that they can be easily identified. Transactions between employees and customers are formalized with stock phrases or scripts and clear directives about how to perform tasks so that nobody has to think. Non-human technologies like self-scanning check-out items reduce human error and human interaction to streamline the shopping process. Surveillance systems and bar code data entry allows management to control consumer and work processes at a distance (control).

While McDonaldization has resulted in improved profits and an increased availability of standardized goods and services to more people worldwide, it has also reduced the variety of goods available in the marketplace while rendering available products uniform, generic, and bland. Think of the difference between a mass-produced shoe and one made by a local cobbler, between a free range chicken from a family-owned farm versus a corporate factory farmer, or a cup of coffee from the local roaster instead of one from a coffee-shop chain. Ritzer also notes that the rational systems, as efficient as they are, are irrational in that they become more important than the people working within them, or the clients being served by them. “Most specifically, irrationality means that rational systems are unreasonable systems. By that I mean that they deny the basic humanity, the human reason, of the people who work within or are served by them” (Ritzer, 2013).

Some contemporary trends can be referred to as “de-McDonaldization:” the resurgence of farmer’s markets, the 100 mile diet and slow-cooking movement, micro-breweries and shop-local campaigns. As a corporate model, Starbucks is often seen as an alternative chain that has abandoned the one-size-fits-all, standardized of service of McDonald’s in a way that is more suited to late modern sensibilities. Principally, it moved away from the mediocre or low quality products of fast food restaurants, refocused on providing comforts for consumers (over-stuffed couches, wooden furniture, wifi, artwork, popular music), branded itself as a kinder, gentler, and caring corporation (fair-trade coffee, calling employees “partners,” etc.) and created a “theatrics” that provides an “experience” of being in an old-fashioned, local coffee-shop (Ritzer, 2013). Nevertheless Starbucks still clearly fits, and operates in accordance with, the four McDonaldization principles of efficiency, predictability, calculability and control, while somehow convincing customers to pay $4 for a coffee. It is also famous for ruthlessly eliminating local competition. On the other hand, with its recent advertising campaigns, changes in menu, and products emphasizing individuality, even McDonald’s might be seen as de-McDonaldizing itself.

Making Connections: Sociological Research

Secrets of the McJob

People often talk about bureaucracies disparagingly, and no organizations have taken more heat than fast-food restaurants. The book and movie Fast Food Nation: The Dark Side of the All-American Meal by Eric Schossler (2001) paints an ugly picture of what goes in, what goes on, and what comes out of fast-food chains. From their environmental impact to their role in the North American obesity epidemic, fast-food chains are connected to numerous societal ills. Furthermore, working at a fast-food restaurant is often disparaged, and even referred to dismissively, as a McJob rather than a real job.

But business school professor Jerry Newman (2007) went undercover and worked behind the counter at seven fast-food restaurants to discover what really goes on there. His book, My Secret Life on the McJob, documents his experience. Newman found, unlike Schossler, that these restaurants have much good alongside the bad. Specifically, he asserted that the employees were honest and hard-working, the management was often impressive, and the jobs required a lot more skill and effort than most people imagined. In the book, Newman cites a pharmaceutical executive who states that a fast-food service job on an applicant’s résumé is a plus because it indicates the employee is reliable and can handle pressure.

The fast food sector is an important industry, employing 394,134 people or 3.7% of Canadians 2021 (Bush, 2023). 28.3% of Canadians have worked directly in the food service industry and almost half of the population have either worked in the industry themselves or someone in their family has or still does. Four out of five people see fast-food restaurants as an important first job source.

So what is the verdict? Are these McJobs and the organizations that offer them still serving a useful role in the economy and people’s careers? Or are they dead-end jobs that typify all that is negative about McDonaldization?

Media Attributions

- Figure 7.20 Bureaucracy illustration by Harald Groven, via Flickr, is used under a CC BY-SA 2.0 licence.

- Figure 7.21 (a) Brownie and Cub compare badges by Girl Guides of Canada, via Flickr, is used under CC BY 2.0 licence; (b) Alouette Correctional Centre by Province of British Columbia, via Flickr, is used under a CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 licence.

- Figure 7.22 McDonald’s in Luxor, Egypt by Sean Ellis, via Flickr, is used under CC BY 2.0 licence.

- Figure 7.23 Tim Hortons Breakfast BELT Bagel Sandwich by Calgary Reviews is used under a CC BY 2.0 licence.