Chapter 16. Media and Popular Culture

Learning Objectives

- Define the “bias of communication” and its impact on society.

- Distinguish between mass media and digital media and their impact on society.

- Describe the evolution and current role of different media, like newspapers, television, and new media.

16.2 Sociological Frameworks for Understanding Media

- Contrast positivist, critical, and interpretive approaches to media.

- Examine violence in the media as an example of a media effect.

- Isolate five different social functions of the media.

- Examine ideology, stereotyping, and gatekeeping as exercises of power through the media.

- Describe the concentration of corporate ownership of media in Canada and its impact on traditional mass media and new digital media.

- Analyze the propaganda model of media bias.

- Describe the circuit of meaning construction in the media — from media encoding to audience to coding.

- Describe three general frameworks in which audiences interpret media representations.

16.3 Media and Postmodern Culture

- Explain the advantages and concerns of media globalization.

- Understand the globalization of technology.

Introduction to Media and Mediated Life

A medium is a means or channel of communication. In large modern societies, the mass media — newspapers, radio, television, social media platforms, etc. — are central agencies for the circulation of information or “messages.” This is interesting to sociologists for a variety of reasons, but top of the list has to be the way in which contemporary life has become thoroughly mediated. Instead of face-to-face communication and traditions of oral story telling, people’s experience of the world is largely through the media.

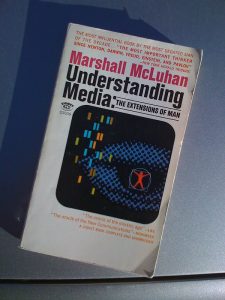

One way of thinking about this is to consider the impact of different types of media on society. As Canadian media theorist Marshall McLuhan put it in 1964, “the medium is the message,” meaning that the specific contents (or messages) presented by the media are less important than the technological form in which they are presented (McLuhan, 1964). McLuhan saw technologies as extensions of various human capacities, and media therefore as an extension of human perception.

McLuhan was especially interested in the social and cultural implications of the transition from print media to electronic media as the dominant source of information in the mid 20th century. Whereas print media were “extensions of the eye” — distancing the reader from what they read, arranging information in linear sequences on the page, lending themselves to categorizing, compartmentalizing and critical analysis — the electronic media like television and radio were “extensions of the human nervous system.” Rather than separating people from the world, the electronic media created an immersive mediascape in which people directly “sensed into” or “felt” the world. Rather than distancing, they were involving. For McLuhan, this described a new mediated relationship of the individual to an increasingly available, global society, one of “total social involvement instead of individual separateness or points of view” (McLuhan, 1964).

For McLuhan, media are literally human prosthetics (like artificial limbs) that extend people’s abilities while altering the organization of their senses. Print media privilege seeing, the objectifying gaze of the eye; electronic media privilege feeling, the “instant, total field-awareness” of the extended nervous system. The type of media shapes the way people connect to the world and structures the nature of their emotional, affectual existence. The media create a sensual environment in which the world is experienced.

“All media work us over completely. They are so pervasive in their personal, political, economic, aesthetic, psychological, moral, ethical, and social consequences that they leave no part of us untouched, unaffected, unaltered” (McLuhan and Fiore, 1967).

Media Representations

It is not necessary to go as far as McLuhan to get a sense of how profoundly the media affect people’s sense of the world and their place within it. Another way of thinking about mediated life is the degree to which people access the world through representations, the use of signs and symbols that stand in for directly lived experiences or referents (Hall, 1997). As the term suggests, much of the world that people interact with on a daily basis is not immediately present or directly experienced, but rather re-presented through images, texts, and narratives, etc. circulated through the media.

The media continually re-present people to themselves; define a society’s collective memory, its present, and its future; name people’s fears, joys, desires, and aspirations; stage what is visible and invisible, what is happening and what is forgotten. They transform the immediacy of life into mediacy by translating real-life events into media “texts” (images, books, films, newspaper articles, television shows, tweets, internet memes), which can be distributed anywhere.

The media are also a communications industry. As a byproduct of the entertainment, news, and information products they sell, they produce mediated forms of proximity and intimacy. They bring people together virtually. Virtuality is the quality of having the attributes of something without sharing its real or imagined physical form. But virtual proximity and intimacy are still real in their effects on people’s lives and social reality. Hatsune Miku is a real virtual idol who motivates people to go out to “see her live” and participate with others in complicated choreographed dance moves.

What are the consequences for social life and social organization when communication moves from the direct face-to-face communications engaged in by humanity for millennia to communications that are mediated by various communications technologies like newspapers and TV, or texting or tweeting? What happens to human proximity and intimacy when communications are sold as commodities in the competitive marketplace, used as “data points” in the collection of personal information, or promoted like in advertising or political messaging?

Questions about media and mediated society can be examined from different sociological perspectives. Positivist approaches tend to discuss media effects — what effects or impacts do media have on audiences? For example, does violence in the media have a measurable effect on audiences? Can McLuhan’s argument about the effects of the shift from print media to electronic media be empirically proven? Positivists who focus on the social functions of media in society would ask: what functions do different media perform in society — social solidarity, social coordination, entertainment, socialization, or social control? Interpretive approaches tend to focus on the construction of meaning in the media and the processes whereby audiences interpret or receive those meanings. For example, interpretive sociologists would examine the codes that operate in media representations, since these codes often are the means by which racial and gender stereotypes, ideologies, or commercial messages are transmitted in the guise of news, information, or entertainment. Critical sociological approaches examine the exercise of power through the media. For example, the sociological focus on media concentration and corporate ownership of the media is a question concerning whose ideas or codes are being transmitted and whose are not.

Media Attributions

- Figure 16.1 DSC03643 by Keripo, via Flickr, is used under a CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 licence.

- Figure 16.2 McLuhan on a dime by Alan Levine, via Flickr, is in the public domain.