Chapter 18. Social Movements and Social Change

Learning Objectives

- Describe different forms of collective behaviour: the crowd, the mass, the public, and the social movement.

- Differentiate between types of crowds: Casual, conventional, expressive and acting crowds.

- Review different explanations of collective behaviour: emergent norm, value-added, and assembling analyses.

- Review examples of social movements on local, regional, national, and global levels.

- Distinguish between different types of social movements: reform, revolutionary, redemptive, alternative, and resistance movements.

- Identify stages of social movements: preliminary, coalescence, institutionalization and decline stages.

- Explore theoretical perspectives on social movements: resource mobilization, framing, and new social movement theory.

- Summarize structural functionalist, critical and symbolic interactionist approaches to social movements.

- Explain how technology can bring about social change.

- Define technology and describe its evolution.

- Understand technological inequality and issues related to unequal access to technology.

- Describe the role of planned obsolescence in technological development.

Introduction to Social Movements and Social Change

One of modern life’s main characteristics is incessant change. As noted in Chapter 3. Culture and Chapter 4. Society and Modern Life , the cultural life of modernity can be described as a series of successive “nows” or “presents,” each of which defines what is modern, new or fashionable for a brief time before fading away into obscurity like the 78 rpm record, the 8 track tape and the CD. Marx and Engels summed up the culture of capitalist society in a phrase, “All that is solid melts into air…” (1977 (1848)). From the ghost towns that dot the Canadian landscape to the expectation of having a lifetime career, every element of modern social life seems “transient, fleeting and contingent,” as the poet Charles Baudelaire (1863) once put it. Everything in modernity moves or is in a state of movement. What accounts for social change and social movement?

Emile Durkheim (1937 (1895)) described the phenomena of social life as falling along a continuum from solid to fluid. Some things like geography, availability of natural resources, population density, buildings and roads, machinery and physical artifacts are relatively fixed and unchanging. Other things, like the formal norms and rules established by institutional life, are subject to periodic revision and change, but tend to last through time as they address enduring social concerns and needs (i.e.,social functions). Finally, Durkheim used an electrical metaphor to describe social currents, “great movements of enthusiasm, indignation, and pity” that “carry us away in spite of ourselves” (Durkheim, 1937). Social currents describe aspects of social life that change all the time. Similarly, a society’s collective representations — all “the ways in which the group conceives of itself in relation to objects which affect it” (Durkheim, 1937) — are much more susceptible to change, fads and flux than institutions and social infrastructure.

Thus Durkheim conceptualized a continuum of social phenomena from the most crystallized “morphological” features of social life, to the normative sphere where life becomes institutionalized and rule bound, to the least crystallized, most ephemeral phenomena of collective representations, social trends, fashion, temporary enthusiasms and fleeting products of collective imagination.

- Morphological qualities (substratum): population, territorial topography, divisions and resources, social infrastructure, material objects

- Institutions (normative sphere): (a) formal rules and norms, legal procedures, moral codes, religious dogmas, etc.; (b) informal customs, collective habits, social obligations

- Collective representations (symbolic sphere): (a) values, ideals, representations, language, stories, symbols; (b) free currents of social life: collective feelings, public opinion and trends, i.e.,social creation in the process of emerging and not yet caught in a definite mould (Thompson, 2002).

Durkheim sums up the idea of a continuum of social stability and variation by noting, “[t]here is thus a whole series of degrees without a break in continuity between the facts of the most articulated structure and those free currents of social life which are not yet definitely moulded. The differences between them are, therefore, only differences in the degree of consolidation they present. Both are simply life, more or less crystallized” (Durkheim, 1937). Social life is caught up in differing degrees of movement and consolidation. Some aspects move slowly and become contained and solidified; other aspects move quickly, caught up in the continuous variation of social currents.

For example, when something “trends” on social media, it becomes a social current in contemporary social life. It is not something that just one person or a few people notice and remark on; it becomes part of a collective awareness. Through likes and shares, people’s attention and feelings turn toward it and it becomes a focus of the collective consciousness, albeit usually temporarily. How would a Durkheimian sociologist analyze it?

Current events, major film releases, celebrity scandals, etc. are likely to trend on social media and then be forgotten almost immediately. They capture momentary enthusiasms and then disappear. However, other trends and social currents prove to be more enduring and find “legs” and purchase in society. The Black Lives Matter movement started as a viral hashtag #BlackLivesMatter when the killer of 17 year old Trayvor Martin was acquitted of murder in 2013 (Ransby, 2018). Similarly, the #metoo movement gained collective attention as a social media hashtag, initially in response to multiple accusations of sexual assault against American film producer Harvey Weinstein in 2017 (Rech, 2019). It invited women to share stories sexual assault and harassment and became a global social movement, involving demonstrations, community work, public debates, prosecutions and policy initiatives. The social media trend created broad social awareness of the issue that lead to a significant increase in the number of women coming forward to report of sexual abuse in Canada. It lead to reviews of workplace harassment policies and of police and prosecutor practices in processing sexual assaults. In both Black Lives Matter and Me Too, a potentially ephemeral social media trend “crystallized” and solidified to become the basis for social movements and institutional change.

Social currents can also crystallize into the most solid, morphological features of social life. Concerns and public opinion about discrimination against non-binary genders can lead to architectural changes, such as provisions for unisex washrooms. After the Great Depression of the 1930s and a period of declining birthrates, the post World War Two trend towards having larger numbers of children earlier in marriage lead to the collective phenomenon of the baby boom. The demographic effects of the baby boom had a profound impact on the built environment (the building of schools and community centers, the suburbanization of cities, the dependence on automobiles and automobile infrastructure), the creation of new social policy and planning as the baby boomers moved through their life cycle (education systems, employment insurance, public healthcare, senior care), and the youth orientation of popular culture (the birth of rock and roll, TV cartoons, youth subcultures, consumer society) (Foot and Cooper, 2013).

It is interesting that the invention of social media themselves constituted a new normative or institutional form of social interaction. Norms are built in to the software of the media platforms such as Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, Youtube, TikTok, etc. The software establishes the forms and networks of communication, including the social connection between users (networks), the contractual relationship between media companies and users, the format of expression (Facebook posts or Twitter’s 240 character limit, for eg.) and software functions such as “likes” and “shares,” which aid in the circulation and overall popularity of posts. They also establish a vast network of surveillance in which trillions of “data points” about individuals lives are accumulated by private corporations and used to sell advertising, suggest objects for attention, and “nudge” or influence behaviour. These factors define the norms of communication in the social media era. These norms are subject to revision and innovation, but also solidify to become habit forming and institutional.

Beneath the trends, software and norms of social media is the morphological infrastructure of digital technology. Fibre optic cables, satellite networks, smart phones and computer chips determine the structure of informational civilization. They have profound effects on the nature of personal privacy and public life, as well as who has access to digital information, where and with how much bandwidth.

The social media example illustrates two aspects of the sociology of social movements and social change discussed in this chapter. What accounts for social change and social movement? Social change can take place through the informal and spontaneous structures of collective behaviour and through the formal and organized structures of social movements. Media trends can become the basis of changes in collective behaviours and social movements when they become channeled and institutionalized. Social change can also be produced by technological innovations, which affect the morphological structure of society. The creation of an informational civilization is the product of the invention, circulation and integration of digital technologies into social life. Both aspects describe the way a society moves and changes.

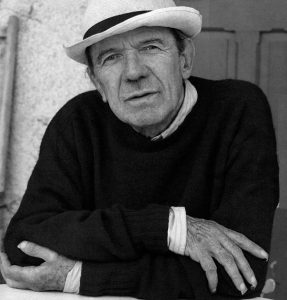

As the philosopher Gilles Deleuze says, what is most interesting about a society is what moves and what escapes its structures: “the movements of flight” which break from established norms, categories and patterns of behaviour (Deleuze and Parnet, 2007). These define the places where societies evolve and transform.

Media Attributions

- Figure 18.1 Protesters re-take Camp Land Back from RCMP at the Fairy Creek Blockade by Joshua Wright, via Wikimedia Commons, is used under a CC BY-SA 4.0 licence.

- Figure 18.2 It’s an 8-Track Tape Player, Baaabbby by Randy Robertson, via Flickr, is used under a CC BY 2.0 licence.

- Figure 18.3 Today’s Top Twitter Trending Worldwide topics in Cloud View by Trends 24, is used under Trends24 Terms and Conditions.

- Figure 18.4 A photograph of Gilles Deleuze by unknown photographer, via Wikimedia Commons, is used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 licence.