3 Chapter 3. Culture

Learning Objectives

- Differentiate between culture and society.

- Distinguish between biological and cultural explanations of human behaviour.

- Compare and contrast cultural universalism, cultural relativism, ethnocentrism, and androcentrism.

- Examine the policy of multiculturalism as a solution to the problem of diversity.

- Understand the basic elements of culture: values, beliefs, and norms.

- Explain the significance of symbols and language to a culture.

- Describe the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis.

- Distinguish material and nonmaterial culture.

3.3. Culture as Innovation: Pop Culture, Subculture, and Global Culture

- Distinguish two modes of culture: innovation and restriction.

- Discuss the distinction between high culture, pop culture, and postmodern culture.

- Differentiate between subculture and counterculture.

- Understand the role of globalization in cultural change and local lived experience.

3.4. Culture as Restriction: Rationalization and Commodification

- Describe culture as a form of restriction on social life.

- Explain the implications of rationalization and consumerism.

3.5. Theoretical Perspectives on Culture

- Discuss the major theoretical approaches to cultural interpretation.

Introduction to Culture

Are there rules for eating at McDonald’s? Generally, we do not think about rules in a fast food restaurant because they are designed to be casual, quick, and convenient. But if you look around one on a typical weekday, you will see people acting as if they were trained for the role of fast food customer. They stand in line, pick their items from overhead menus before they order, swipe debit cards to pay, and stand to one side to collect trays of food. After a quick meal, customers wad up their paper wrappers and toss them into garbage cans. This is a food system that has become highly rationalized in Max Weber’s terms. Customers’ movement through this fast food routine is orderly and predictable, even if no rules are posted and no officials direct the process.

If you want more insight into these unwritten rules, think about what would happen if you behaved according to some other standards. (You would be doing what sociologists call a “breaching experiment” in ethnomethodology: deliberately disrupting social norms in order to learn about them.) For example: call ahead for reservations; ask the cashier detailed questions about the food’s ingredients or how it is prepared; barter over the price of the burgers; ask to have your meal served to you at your table; or throw your trash on the ground as you leave. Chances are you will elicit hostile responses from the restaurant employees and your fellow customers. Although the rules are not written down, you will have violated deep seated tacit norms that govern behaviour in fast food restaurants.

This example reflects a broader theme in the culture of food and diet. What are the rules that govern what, when, and how we eat? Michael Pollan (b. 1955), for example, contrasts the North American culture of fast food with the intact traditions of eating sit-down, family meals that still dominate in France and other European nations (2006). Despite eating foods that many North Americans think of as unhealthy — butter, wheat, triple-cream cheese, foie gras, wine, etc. — the French, as a whole, remain healthier and thinner than North Americans.

The French eat all sorts of supposedly unhealthy foods, but they do it according to a strict and stable set of rules: They eat small portions and don’t go back for seconds; they don’t snack; they seldom eat alone; and communal meals are long, leisurely affairs. (Pollan, 2006)

Their cultural rules fix and constrain what people consider as food and how people consume food. The national cuisine and eating habits of France are well established, oriented to pleasure and tradition, and as Pollan argues, well integrated into French cultural life as a whole.

In North America, on the other hand, fast food is just the tip of an iceberg with respect to a larger crisis of diet in which increasing levels of obesity and eating disorders are coupled with an increasing profusion of health diets, weight reducing diets, and food fads. While an alarming number of North American meals are eaten in cars (19 percent, according to Pollan), the counter-trend is the obsession with nutritional science. Instead of an orientation to food based on cultural tradition and pleasure, people are oriented to food in terms of its biochemical constituents (calories, proteins, carbohydrates, vitamins, omega fatty acids, saturated and unsaturated fats, etc.). There are Atkins diets, zone diets, Mediterranean diets, paleolithic diets, vegan diets, gluten free diets, Weight Watchers diets, raw food diets, etc.; an endless proliferation that Pollan attributes to a fundamental anxiety that North Americans have about food and health. While each type of diet claims scientific evidence to support its health and other claims, evidence which is disturbingly contradictory, essentially the choice of diet revolves around the cultural meanings attributed to food and its nutritional components:

that taste is not a true guide to what should be eaten; that one should not simply eat what one enjoys; that the important components of food cannot be seen or tasted, but are discernible only in scientific laboratories; and that experimental science has produced rules of nutrition that will prevent illness and encourage longevity. (Levenstein as cited in Pollan, 2006)

It is important to note that food culture and diet are not infinitely malleable, however. There is an underlying biological reality of nutrition that defines the parameters of dietary choice. In his documentary Super Size Me (2004), Morgan Spurlock conducted a version of the sociological participant observation study by committing himself to eating only McDonald’s food for 30 days. As a result, he gained 24 pounds, increased his cholesterol and fat accumulation in his liver, and experienced mood swings and sexual dysfunction. It is clear that one cannot survive on fast food alone; although many teenagers and university students have been known to try.

Sociologists would argue, therefore, that everything about fast food restaurants, choice of diet, and habits of food consumption reflects culture, the beliefs and behaviours that a social group shares. Diet is a product of culture. It is a product of the different meanings we attribute to food and to the relationship we have with our bodies. The significant point is that while diet is a response to the fundamental conditions of biological life, diet is also a tremendous site of innovation and diversity. Culture in general is a site of two opposing tendencies: one is the way that cultures around the world lay down sets of rules or norms which constrain, restrict, habitualize, and fix forms of life; the other is the way that cultures produce endlessly innovative and diverse solutions to problems like nutrition. Cultures both constrain and continually go beyond constraints.

This raises the distinction between the terms “culture” and “society” and how sociologists conceptualize the relationship between them. In everyday conversation, people rarely distinguish between these terms, but they have slightly different meanings, and the distinction is important to how sociologists examine culture. If culture refers to the beliefs, artifacts, and ways of life that a social group shares, a society is a group that interacts within a common bounded territory or region. To clarify, a culture represents the beliefs, practices, and material artifacts of a group, while a society represents the social structures, processes, and organization of the people who share those beliefs, practices, and material artifacts. Neither society nor culture could exist without the other, but we can separate them analytically.

In this chapter, we examine the relationship between culture and society in greater detail, paying special attention to the elements and forces that shape culture, including diversity and cultural changes. A final discussion touches on the different theoretical perspectives from which sociologists research culture.

3.1. What Is Culture?

Humans are social creatures. Since the dawn of Homo sapiens, nearly 200,000 years ago, people have grouped together into communities in order to survive. Living together, people developed forms of cooperation which created the common habits, behaviours, and ways of life known as culture — from specific methods of childrearing to preferred techniques for obtaining food. Peter Berger (b. 1929) argued that this is the result of a fundamental human predicament (1967). Unlike other animals, humans lack the biological programming to live on their own. They require an extended period of dependency in order to survive in the environment. The creation of culture makes this possible by providing a protective shield against the harsh impositions of nature. Culture provides the ongoing stability that enables human existence. This means, however, that the human environment is not nature per se but culture itself.

Over the history of humanity, this has lead to an incredible diversity in how humans have imagined and lived life on Earth, the sum total of which Wade Davis (b. 1953) has called the ethnosphere. The ethnosphere is the entirety of all cultures’ “ways of thinking, ways of being, and ways of orienting oneself on the Earth” (Davis, 2007). It is our collective cultural heritage as a species. A single culture, as the sphere of meanings shared by a single social group, is the means by which that group makes sense of the world and of each other. But there are many cultures and many ways of making sense of the world. Through a multiplicity of cultural inventions, human societies have adapted to the environmental and biological conditions of human existence in many different ways. What do we learn from this?

Firstly, almost every human behaviour, from shopping to marriage to expressions of feelings, is learned. In Canada, people tend to view marriage as a choice between two people based on mutual feelings of love. In other nations and in other times, marriages have been arranged through an intricate process of interviews and negotiations between entire families, or in other cases, through a direct system such as a mail-order bride. To someone raised in Winnipeg, the marriage customs of a family from Nigeria may seem strange or even wrong. Conversely, someone from a traditional Kolkata family might be perplexed with the idea of romantic love as the foundation for the lifelong commitment of marriage. In other words, the way in which people view marriage depends largely on what they have been taught. Being familiar with these written and unwritten rules of culture helps people feel secure and “normal.” Most people want to live their daily lives confident that their behaviours will not be challenged or disrupted. Behaviour based on learned customs is, therefore, not a bad thing, but it does raise the problem of how to respond to cultural differences.

Secondly, culture is innovative. The existence of different cultural practices reveals the way in which societies find different solutions to real life problems. The different forms of marriage are various solutions to a common problem, the problem of organizing families in order to raise children and reproduce the species. The basic problem is shared by the different societies, but the solutions are different. This illustrates the point that culture in general is a means of solving problems. It is a tool composed of the capacity to abstract and conceptualize, to cooperate and coordinate complex collective endeavours, and to modify and construct the world to suit human purposes. It is the repository of creative solutions, techniques, and technologies humans draw on when confronting the basic shared problems of human existence. Culture is, therefore, key to the way humans, as a species, have successfully adapted to the environment. The existence of different cultures refers to the different means by which humans use innovation to free themselves from biological and environmental constraints.

Thirdly, culture is also restraining. Cultures retain their distinctive patterns through time. In global capitalism, although Canadian culture, French culture, Malaysian culture and Kazakhstani culture will share certain features like rationalization and commodification, they also differ in terms of languages, beliefs, dietary practices, and other ways of life. They adapt and respond to capitalism in unique manners according to their specific shared heritages. Local cultural forms have the capacity to restrain the changes produced by globalization. On the other hand, the diversity of local cultures is increasingly limited by the homogenizing pressures of globalization. Economic practices that prove inefficient or uncompetitive in the global market disappear. The meanings of cultural practices and knowledges change as they are turned into commodities for tourist consumption or are patented by pharmaceutical companies. Globalization increasingly restrains cultural forms, practices, and possibilities.

There is a dynamic within culture of innovation and restriction. The cultural fabric of shared meanings and orientations that allows individuals to make sense of the world and their place within it can either change with contact with other cultures or with changes in the socioeconomic formation, allowing people to reinvision and reinvent themselves, or it can remain rigid and restrict change. Many contemporary issues to do with identity and belonging, from multiculturalism and hybrid identities to religious fundamentalism, can be understood within this dynamic of innovation and restriction. Similarly, the effects of social change on ways of life, from the new modes of electronic communication to failures to respond to climate change, involve a tension between innovation and restriction.

Making Connections: Sociological Concepts

“Yes, but what does it mean?”

The premise we will be exploring in this chapter is that the human world, unlike the natural world, cannot be understood unless its meaningfulness is taken into account. Human experience is essentially meaningful, and culture is the source of the meanings that humans share. What are the consequences of this emphasis on the meaningfulness of human experience? What elements of social life become visible if we focus on the social processes whereby meanings are produced and circulated?

Culture is the term used to describe this dimension of meaningful collective existence. Culture refers to the shared symbols that people create to solve real-life problems. What this perspective entails is that human experience is essentially meaningful or cultural. Human social life is necessarily conducted through the meanings humans attribute to things, actions, others, and themselves. In a sense, people do not live in direct, immediate contact with the world and each other; instead, they live only indirectly through the medium of the shared meanings provided by culture. This mediated experience is the experience of culture. As the philosopher Martin Heidegger put it, humans live in an “openness” granted by language and by their ability to respond to the meaningfulness of things in a way that other living beings do not. The sociology of culture is, therefore, concerned with the study of how things and actions assume meanings, how these meanings orient human behaviour, and how social life is organized around and through meaning.

What is the “meaning of meaning” in social life, therefore? Max Weber notes that it is possible to imagine situations in which human experience appears direct and unmediated; for example, someone taps your knee and your leg jerks forward, or you are riding your bike and get hit by a car (1968, pp. 94–96). In these situations, experience seems purely physical, unmediated. Yet when we assimilate these experiences into our lives, we do so by making them meaningful events. By tapping your knee, the doctor is looking for signs that indicate the functioning of your nervous system. She or he is literally reading the reactions as symbolic events and assigning them meaning within the context of an elaborate cultural map of meaning: the modern biomedical understanding of the body. It is quite possible that if you were flying through the air after being hit by a car, you would not be thinking or attributing meaning to the event. You would be simply a physical projectile. But afterwards, when you reconstruct the story for your friends, the police, or the insurance company, the event would become part of your life through this narration of what happened.

Equally important to note here is that the meaning of these events changes depending on the cultural context. A doctor of traditional Chinese medicine would read the knee reflex differently than a graduate of the UBC medical program. The story and meaning of the car accident changes if it is told to a friend as opposed to a policeman or an insurance adjuster.

The problem of meaning in sociological analysis, then, is to determine how events or things acquire meaning (e.g., through the reading of symptoms or the telling of stories); how the true or right meanings are determined (e.g., through biomedically-based diagnoses or juridical procedures of determining responsibility); how meaning works in the organization of social life (e.g., through the medicalized relation to our bodies or the norms of traffic circulation); and how humans gain the capacity to interpret and share meanings in the first place (e.g., through the process of socialization into medical, legal, insurance, and traffic systems). Sociological research into culture studies all of these problems of meaning.

Culture and Biology

The central argument put forward in this chapter is that human social life is essentially meaningful and, therefore, has to be understood first through an analysis of the cultural practices and institutions that produce meaning. Nevertheless, a fascination in contemporary culture persists for finding biological or genetic explanations for complex human behaviours that would seem to contradict the emphasis on culture.

In one study, Swiss researchers had a group of women smell unwashed T-shirts worn by different men. The researchers argued that sexual attraction had a biochemical basis in the histo-compatibility signature that the women detected in the male pheromones left behind on the T-shirts. Women were attracted to the T-shirts of the men whose immune systems differed from their own (Wedekind et al., 1995). In another study, Dean Hamer (b. 1951) and his colleagues discovered that some homosexual men possessed the same region of DNA on their X chromosome, which led them to argue that homosexuality was determined genetically by a “gay gene” (Hamer et al., 1993). Another study found that the corpus callosum, the region of nerve fibres that connect the left and right brain hemispheres, was larger in women’s brains than in men’s (De Lacoste-Utamsing & Holloway, 1982). Therefore, women were thought to be able to use both sides of their brains simultaneously when processing visuo-spatial information, whereas men used only their left hemisphere. This finding was said to account for gender differences that ranged from women’s supposedly greater emotional intuition to men’s supposedly greater abilities in math, science, and parallel parking. In each of these three cases, the authors reduced a complex cultural behaviour — sexual attraction, homosexuality, cognitive ability — to a simple biological determination.

In each of these studies, the scientists’ claims were quite narrow and restricted in comparison to the conclusions drawn from them in the popular media. Nevertheless, they follow a logic of explanation known as biological determinism, which argues that the forms of human society and human behaviour are determined by biological mechanisms like genetics, instinctual behaviours, or evolutionary advantages. Within sociology, this type of framework underlies the paradigm of sociobiology, which provides biological explanations for the evolution of human behaviour and social organization.

Sociobiological propositions are constructed in three steps (Lewontin, 1991). First they identify an aspect of human behaviour which appears to be universal, common to all people in all times and places. In all cultures the laws of sexual attraction — who is attracted to whom — are mysterious, for example. Second, they assume that this universal trait must be coded in the DNA of the species. There is a gene for detecting histo-compatibility that leads instinctively to mate selection. Third, they make an argument for why this behaviour or characteristic increases the chances of survival for individuals and, therefore, creates reproductive advantage. Mating with partners whose immune systems complement your own leads to healthier offspring who survive to reproduce your genes. The implication of the sociobiological analysis is that these traits and behaviours are fixed or “hard wired” into the biological structure of the species and are, therefore, very difficult to change. People will continue to be attracted to people who are not “right” for them in all the ways we would deem culturally appropriate — psychologically, emotionally, socially compatible, etc. — because they are biologically compatible.

Despite the popularity of this sort of reason, it is misguided from a sociological perspective for a number of reasons. For example, Konrad Lorenz’s (1903-1989) arguments that human males have an innate biological aggressive tendency to fight for scarce resources and protect territories were very popular in the 1960s (1966). The dilemma he posed was that males’ innate tendency towards aggression as a response to external threats might be a useful trait on an evolutionary scale, but in a contemporary society that includes the development of weapons of mass destruction, it is a threat to human survival. Another implication of his argument was that if aggression is instinctual, then the idea that individuals, militant groups, or states could be held responsible for acts of violence or war loses its validity. (Note here that Lorenz’s basic claim about aggression runs counter to the stronger argument that, if anything, the tendency toward co-operation has been central to the survival of human social life from its origins to the present).

However, a central problem of sociobiology as a type of sociological explanation is that while human biology does not vary greatly throughout history or between cultures, the forms of human association do vary extensively. It is difficult to account for the variability of social phenomena by using a universal biological mechanism to explain them. Even something like the aggressive tendency in males, which on the surface has an intuitive appeal, does not account for the multitude of different forms and practices of aggression, let alone the different social circumstances in which aggression is manifested or provoked. It does not account for why some men are aggressive sometimes and not at other times, or why some men are not aggressive at all. It does not account for women’s aggression and the forms in which this typically manifests. If testosterone is the key mechanism of male aggression, it does not account for the fact that both men and women generate testosterone in more or less equal quantities. Nor does it explain the universal tendencies of all societies to develop sanctions and norms to curtail violence. To suggest that aggression is an innate biological characteristic means that it does not vary greatly throughout history, nor between cultures, and is impervious to the social rules that restrict it in all societies. Ultimately, this means that there is no point in trying change it despite the evidence that aggression in individuals and societies can be changed.

The main consideration to make here is not that biology has no impact on human behaviour, but that the biological explanation is limited with respect to what it can explain about complex cultural behaviours and practices. For example, research has shown that newborns and fetuses as young as 26 weeks have a simple smile: “the face relaxes while the sides of the mouth stretch outward and up” (Fausto-Sterling, 2000). This observation about a seemingly straightforward biological behaviour suggests that smiling is inborn, a muscular reflex based on neurological connections. However, the smile of the newborn is not used to convey emotions. It occurs spontaneously during rapid eye movement (REM) sleep. Only when the baby matures and begins to interact with his or her environment and caretakers does the smile begin to represent a response to external stimuli. By age one, the baby’s smile conveys a variety of meanings, depending on the social context, including flirting and mischief. Moreover, from the age of 6 months to 2 years, the smile itself changes physically: Different muscle groups are used, and different facial expressions are blended with it (surprise, anger, excitement). The smile becomes more complex and individualized. The point here, as Anne Fausto-Sterling points out, is that “the child uses smiling as part of a complex system of communication” (2000). Not only is the meaning of the smile defined in interaction with the social context, but the physiological components of smiling (the nerves, muscles, and stimuli) also are modified and “socialized” according to culture.

Therefore, social scientists see explanations of human behaviour based on biological determinants as extremely limited in scope and value. The physiological “human package” — bipedalism, omnivorous diet, language ability, brain size, capacity for empathy, lack of an estrous cycle (Naiman, 2012) — is more or less constant across cultures; whereas, the range of cultural behaviours and beliefs is extremely broad. These sometimes radical differences between cultures have to be accounted for instead by their distinct processes of socialization through which individuals learn how to participate in their societies. From this point of view, as the anthropologist Margaret Mead (1901-1978) put it:

We are forced to conclude that human nature is almost unbelievably malleable, responding accurately and contrastingly to contrasting cultural conditions. The differences between individuals who are members of different cultures, like the differences between individuals within a culture, are almost entirely to be laid to differences in conditioning, especially during early childhood, and the form of this conditioning is culturally determined (1935).

Aside from the explanatory problems of biological determinism, it is important to bear in mind the social consequences of biological determinism, as these ideas have been used to support rigid cultural ideas concerning race, gender, disabilities, etc. that have their legacy in slavery, racism, gender inequality, eugenics programs, and the sterilization of “the unfit.” Eugenics, meaning “well born” in ancient Greek, was a social movement that sought to improve the human “stock” through selective breeding and sterilization. Its founder, Francis Galton (1822-1911) defined eugenics in 1883 as “the study of the agencies under social control that may improve or impair the racial qualities of future generations, either physically or mentally” (Galton as cited in McLaren, 1990). In Canada, eugenics boards were established by the governments of Alberta and British Columbia to enable the sterilization of the “feeble-minded.” Based on a rigid cultural concept of what a proper human was, and grounded in the biological determinist framework of evolutionary science, 4,725 individuals were proposed for sterilization in Alberta and 2,822 of them were sterilized between 1928 and 1971. The racial component of the program is evident in the fact that while First Nations and Métis peoples made up only 2.5% of the population of Alberta, they accounted for 25% of the sterilizations. Several hundred individuals were also sterilized in British Columbia between 1933 and 1979 (McLaren, 1990).

The interesting question that these biological explanations of complex human behaviour raise is: Why are they so popular? What is it about our culture that makes the biological explanation of behaviours or experiences like sexual attraction, which we know from personal experience to be extremely complicated and nuanced, so appealing? As micro-biological technologies like genetic engineering and neuro-pharmaceuticals advance, the very real prospect of altering the human body at a fundamental level to produce culturally desirable qualities (health, ability, intelligence, beauty, etc.) becomes possible, and, therefore, these questions become more urgent.

Making Connections: Sociology in the Real World

The Pop Gene

The concept of the gene and the idea of genetic engineering have entered into popular consciousness in a number of strange and interesting ways, which speak to our enduring fascination with biological explanations of human behaviour. Some sociologists have begun to speak of a new eugenics movement in reference to the way the mapping and testing of the genome makes it possible, as a matter of consumer choice, to manipulate the genes of a foetus or an egg to eliminate what are considered birth “defects” or to produce what are considered desired qualities in a child. If the old eugenics movement promoted selective breeding and forced sterilization in order to improve the biological qualities and, in particular, the racial qualities of whole populations, the new eugenics is focused on calculations of individual risk or individual self-improvement and self-realization. In the new eugenics, individuals choose to act upon the genetic information provided by doctors, geneticists, and counsellors to make decisions for their children or themselves (Rose, 2007).

This movement is based both on the commercial aspirations of biotechnology companies and the logic of a new biological determinism or geneticism, which suggests that the qualities of human life are caused by genes (Rose, 2007). The concept of the gene is a relatively recent addition to the way in which people begin to think about themselves in relationship to their bodies. The German historians Barbara Duden and Silja Samerski argue that the gene has become a kind of primordial reference point for the fundamental questions people ask about themselves (2007): Where do I come from; who am I; and what will happen to me in the future? The gene has shifted from its specific place within the parameters of medical science to become a source of popular understanding and speculation: a “pop gene.” Most tellingly, the gene has become a Trojan horse through which “risk consciousness” is implanted in people’s bodies. The popularization of the idea of the gene entails the development of a new relationship to the human body, health, and the genetic predispositions to health risks as we age.

In 2013, the movie star Angelina Jolie underwent a double mastectomy, not because she had breast cancer but because doctors estimated she had an 87 percent chance of developing breast cancer due to a mutation in the BRCA1 gene (Jolie, 2013). On the basis of what might happen to her based on probabilities of risk from genetic models she decided to take drastic measures to avoid the breast cancer that her mother died of. Her very public stance on her surgery was to raise public awareness of the genetic risks of cancers that run in families and to normalize a medical procedure that many would be hesitant to take. At the same time she further implanted a notion of the gene as a site of invisible risk in peoples lives, encouraging more people to think about themselves in terms of their hidden dispositions to genetically programmed diseases.

Many misconceptions exist in popular culture about what a gene actually is or what it can do. Some of these misconceptions are funny — Duden and Samerski cite a hairdresser they interviewed as saying that her nail biting habit was part of the nature she was born with — but some of them have serious consequences that can lead to the impossible decisions some individuals, including couples who are having a child, are forced to make. Informed decision making in genetic counselling often works with statistical probabilities of “defects” based on population data (e.g., “With your family history, you have a 1 in 10 chance of having a child with the genetic mutation for Down’s syndrome”), but what does this mean to a particular individual? The actual causal mechanism for that particular individual is unknown (i.e., it is unlikely that they will actually have 10 children, one of whom might have Down’s syndrome); therefore, what does this probability figure mean to someone who is pregnant? In this sense, the gene defines a set of cultural parameters by which people in the age of genetics make sense of themselves in relationship to their bodies. Like biological determinism in general, the gene introduces a kind of fatalism into the understanding of human life and human possibility.

Cultural Universals

Often, a comparison of one culture to another will reveal obvious differences. But all cultures share common elements. Cultural universals are patterns or traits that are globally common to all societies. One example of a cultural universal is the family unit: Every human society recognizes a family structure that regulates sexual reproduction and the care of children. Even so, how that family unit is defined and how it functions vary. In many Asian cultures, for example, family members from all generations commonly live together in one household. In these cultures, young adults will continue to live in the extended household family structure until they marry and join their spouse’s household, or they may remain and raise their nuclear family within the extended family’s homestead. In Canada, by contrast, individuals are expected to leave home and live independently for a period before forming a family unit consisting of parents and their offspring.

Anthropologist George Murdock (1897-1985) first recognized the existence of cultural universals while studying systems of kinship around the world. Murdock found that cultural universals often revolve around basic human survival, such as finding food, clothing, and shelter, or around shared human experiences, such as birth and death, or illness and healing. Through his research, Murdock identified other universals including language, the concept of personal names, and, interestingly, jokes. Humour seems to be a universal way to release tensions and create a sense of unity among people (Murdock, 1949). Sociologists consider humour necessary to human interaction because it helps individuals navigate otherwise tense situations.

Making Connections: Sociological Research

Is Music a Cultural Universal?

Imagine that you are sitting in a theatre, watching a film. The movie opens with the hero sitting on a park bench with a grim expression on her face. Cue the music. The first slow and mournful notes are played in a minor key. As the melody continues, the hero turns her head and sees a man walking toward her. The music slowly gets louder, and the dissonance of the chords sends a prickle of fear running down your spine. You sense that she is in danger.

Now imagine that you are watching the same movie, but with a different soundtrack. As the scene opens, the music is soft and soothing with a hint of sadness. You see the hero sitting on the park bench and sense her loneliness. Suddenly, the music swells. The woman looks up and sees a man walking toward her. The music grows fuller, and the pace picks up. You feel your heart rise in your chest. This is a happy moment.

Music has the ability to evoke emotional responses. In television shows, movies, and even commercials, music elicits laughter, sadness, or fear. Are these types of musical cues cultural universals?

In 2009, a team of psychologists, led by Thomas Fritz of the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences in Leipzig, Germany, studied people’s reactions to music they’d never heard (Fritz et al., 2009). The research team travelled to Cameroon, Africa, and asked Mafa tribal members to listen to Western music. The tribe, isolated from Western culture, had never been exposed to Western culture and had no context or experience within which to interpret its music. Even so, as the tribal members listened to a Western piano piece, they were able to recognize three basic emotions: happiness, sadness, and fear. Music, it turns out, is a sort of universal language.

Researchers also found that music can foster a sense of wholeness within a group. In fact, scientists who study the evolution of language have concluded that originally language (an established component of group identity) and music were one (Darwin, 1871). Additionally, since music is largely nonverbal, the sounds of music can cross societal boundaries more easily than words. Music allows people to make connections where language might be a more difficult barricade. As Fritz and his team found, music and the emotions it conveys can be cultural universals.

Ethnocentrism and Cultural Relativism

Despite how much humans have in common, cultural differences are far more prevalent than cultural universals. For example, while all cultures have language, analysis of particular language structures and conversational etiquette reveals tremendous differences. In some Middle Eastern cultures, it is common to stand close to others in conversation. North Americans keep more distance, maintaining a large personal space. Even something as simple as eating and drinking varies greatly from culture to culture. If your professor comes into an early morning class holding a mug of liquid, what do you assume she is drinking? In Canada, it’s most likely filled with coffee, not Earl Grey tea, a favourite in England, or yak butter tea, a staple in Tibet.

The way cuisines vary across cultures fascinates many people. Some travellers, like celebrated food writer Anthony Bourdain, pride themselves on their willingness to try unfamiliar foods, while others return home expressing gratitude for their native culture’s fare. Canadians might express disgust at other cultures’ cuisine, thinking it is gross to eat meat from a dog or guinea pig for example, while they do not question their own habit of eating cows or pigs. Such attitudes are an example of ethnocentrism, or evaluating and judging another culture based on how it compares to one’s own cultural norms. Ethnocentrism, as sociologist William Graham Sumner (1840-1910) described the term, involves a belief or attitude that one’s own culture is better than all others (1906). Almost everyone is a little bit ethnocentric. For example, Canadians tend to say that people from England drive on the “wrong” side of the road, rather than the “other” side. Someone from a country where dogs are considered dirty and unhygienic might find it off-putting to see a dog in a French restaurant.

A high level of appreciation for one’s own culture can be healthy; a shared sense of community pride, for example, connects people in a society. But ethnocentrism can lead to disdain or dislike for other cultures, causing misunderstanding and conflict. People with the best intentions sometimes travel to a society to “help” its people, seeing them as uneducated or backward, essentially inferior. In reality, these travellers are guilty of cultural imperialism — the deliberate imposition of one’s own cultural values on another culture. Europe’s colonial expansion, begun in the 16th century, was often accompanied by a severe cultural imperialism. European colonizers often viewed the people in the lands they colonized as uncultured savages who were in need of European governance, dress, religion, and other cultural practices. On the West Coast of Canada, the Aboriginal potlatch (gift-giving) ceremony was made illegal in 1885 because it was thought to prevent Aboriginal peoples from acquiring the proper industriousness and respect for material goods required by civilization. A more modern example of cultural imperialism may include the work of international aid agencies who introduce modern technological agricultural methods and plant species from developed countries while overlooking indigenous varieties and agricultural approaches that are better suited to the particular region.

Ethnocentrism can be so strong that when confronted with all the differences of a new culture, one may experience disorientation and frustration. In sociology, we call this culture shock. A traveller from Toronto might find the nightly silence of rural Alberta unsettling, not peaceful. An exchange student from China might be annoyed by the constant interruptions in class as other students ask questions — a practice that is considered rude in China. Perhaps the Toronto traveller was initially captivated with Alberta’s quiet beauty, and the Chinese student was originally excited to see an Canadian-style classroom firsthand. But as they experience unanticipated differences from their own culture, their excitement gives way to discomfort and doubts about how to behave appropriately in the new situation. Eventually, as people learn more about a culture, they recover from culture shock.

Culture shock may appear because people are not always expecting cultural differences. Anthropologist Ken Barger discovered this when conducting participatory observation in an Inuit community in the Canadian Arctic (1971). Originally from Indiana, Barger hesitated when invited to join a local snowshoe race. He knew he’d never hold his own against these experts. Sure enough, he finished last, to his mortification. But the tribal members congratulated him, saying, “You really tried!” In Barger’s own culture, he had learned to value victory. To the Inuit people winning was enjoyable, but their culture valued survival skills essential to their environment: How hard someone tried could mean the difference between life and death. Over the course of his stay, Barger participated in caribou hunts, learned how to take shelter in winter storms, and sometimes went days with little or no food to share among tribal members. Trying hard and working together, two nonmaterial values, were indeed much more important than winning.

During his time with the Inuit, Barger learned to engage in cultural relativism. Cultural relativism is the practice of assessing a culture by its own standards rather than viewing it through the lens of one’s own culture. The anthropologist Ruth Benedict (1887–1948) argued that each culture has an internally consistent pattern of thought and action, which alone could be the basis for judging the merits and morality of the culture’s practices. Cultural relativism requires an open mind and a willingness to consider, and even adapt to, new values and norms. The logic of cultural relativism is at the basis of contemporary policies of multiculturalism. However, indiscriminately embracing everything about a new culture is not always possible. Even the most culturally relativist people from egalitarian societies, such as Canada — societies in which women have political rights and control over their own bodies — would question whether the widespread practice of female genital circumcision in countries such as Ethiopia and Sudan should be accepted as a part of a cultural tradition.

Sociologists attempting to engage in cultural relativism may struggle to reconcile aspects of their own culture with aspects of a culture they are studying. Pride in one’s own culture does not have to lead to imposing its values on others. Nor does an appreciation for another culture preclude individuals from studying it with a critical eye. In the case of female genital circumcision, a universal right to life and liberty of the person conflicts with the neutral stance of cultural relativism. It is not necessarily ethnocentric to be critical of practices that violate universal standards of human dignity that are contained in the cultural codes of all cultures, (while not necessarily followed in practice). Not every practice can be regarded as culturally relative. Cultural traditions are not immune from power imbalances and liberation movements that seek to correct them.

Feminist sociology is particularly attuned to the way that most cultures present a male-dominated view of the world as if it were simply the view of the world. Androcentricism is a perspective in which male concerns, male attitudes, and male practices are presented as “normal” or define what is significant and valued in a culture. Women’s experiences, activities, and contributions to society and history are ignored, devalued, or marginalized.

As a result the perspectives, concerns, and interests of only one sex and class are represented as general. Only one sex and class are directly and actively involved in producing, debating, and developing its ideas, in creating its art, in forming its medical and psychological conceptions, in framing its laws, its political principles, its educational values and objectives. Thus a one-sided standpoint comes to be seen as natural, obvious, and general, and a one-sided set of interests preoccupy intellectual and creative work. (Smith, 1987)

In part this is simply a question of the bias of those who have the power to define cultural values, and in part it is the result of a process in which women have been actively excluded from the culture-creating process. It is still common, for example, to read writing that uses the personal pronoun “he” or the word “man” to represent people in general or humanity. The overall effect is to establish masculine values and imagery as normal. A “policeman” brings to mind a man who is doing a “man’s job”, when in fact women have been involved in policing for several decades now.

Making Connections: Social Policy and Debate

Multiculturalism in Canada

One prominent aspect of contemporary Canadian cultural identity is the idea of multiculturalism. Canada was the first officially declared multicultural society in which, as Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau declared in 1971, no culture would take precedence over any other. Multiculturalism refers to both the fact of the existence of a diversity of cultures within one territory and to a way of conceptualizing and managing cultural diversity. As a policy, multiculturalism seeks to both promote and recognize cultural differences while addressing the inevitability of cultural tensions. In the 1988 Multiculturalism Act, the federal government officially acknowledged its role “in bringing about equal access and participation for all Canadians in the economic, social, cultural, and political life of the nation” (Government of Canada, as cited in Angelini & Broderick, 2012).

However, the focus on multiculturalism and culture per se has not always been so central to Canadian public discourse. Multiculturalism represents a relatively recent cultural development. Prior to the end of World War II, Canadian authorities used the concept of biological race to differentiate the various types of immigrants and Aboriginal peoples in Canada. This focus on biology led to corresponding fears about the quality of immigrant “stock” and the problems of how to manage the mixture of races. In this context, three different models for how to manage diversity were in contention: (1) the American “melting pot” paradigm in which the mingling of races was thought to be able to produce a super race with the best qualities of all races intermingled, (2) strict exclusion or deportation of races seen to be “unsuited” to Canadian social and environmental conditions, or (3) the Canadian “mosaic” that advocated for the separation and compartmentalization of races (Day, 2000).

After World War II, the category of race was replaced by culture and ethnicity in the public discourse, but the mosaic model was retained. Culture came to be understood in terms of the new anthropological definitions of culture as a deep-seated emotional-psychological phenomenon. In this conceptualization, to be deprived of culture through coercive assimilation would be a type of cultural genocide. As a result, alternatives to cultural assimilation into the dominant Anglo-Saxon culture were debated, and the Canadian mosaic model for managing a diverse population was redefined as multiculturalism. Based on a new appreciation of culture, and with increased immigration from non-European countries, Canadian identity was re-imagined in the 1960s and 1970s as a happy cohabitation of cultures, each of which was encouraged to maintain their cultural distinctiveness. So while the cultural identity of Canadians is diverse, the cultural paradigm in which their coexistence is conceptualized — multiculturalism — has come to be equated with Canadian cultural identity.

However, these developments have not alleviated the problems of cultural difference with which sociologists are concerned. Multicultural policy has sparked numerous, remarkably contentious issues ranging from whether Sikh RCMP officers can wear turbans to whether Mormon sects can have legal polygamous marriages. In 2014, the Parti Québécois in Quebec proposed a controversial Charter of Quebec Values that would, to reinforce the neutrality of the state, ban public employees from wearing “overt and conspicuous” religious symbols and headgear. This position represented a unique Quebec-based concept of multiculturalism known as interculturalism. Whereas multiculturalism begins with the premise that there is no dominant culture in Canada, interculturalism begins with the premise that in Quebec francophone culture is dominant but also precarious in the North American context. It cannot risk further fragmentation. Therefore the intercultural model of managing diversity is to recognize and respect the diversity of immigrants who seek to integrate into Quebec society but also to make clear to immigrants that they must recognize and respect Quebec’s common or “fundamental” values.

Critics of multiculturalism identify four related problems:

- Multiculturalism only superficially accepts the equality of all cultures while continuing to limit and prohibit actual equality, participation, and cultural expression. One key element of this criticism is that there are only two official languages in Canada — English and French — which limits the full participation of non-anglophone/francophone groups.

- Multiculturalism obliges minority individuals to assume the limited cultural identities of their ethnic group of origin, which leads to stereotyping minority groups, ghettoization, and feeling isolated from the national culture.

- Multiculturalism causes fragmentation and disunity in Canadian society. Minorities do not integrate into existing Canadian society but demand that Canadians adopt or accommodate their way of life, even when they espouse controversial values, laws, and customs (like polygamy or sharia law).

- Multiculturalism is based on recognizing group rights which undermines constitutional protections of individual rights.

On the other hand, proponents of multiculturalism like Will Kymlicka describe the Canadian experience with multiculturalism as a success story. Kymlicka argues that the evidence shows:

“Immigrants in Canada are more likely to become citizens, to vote and to run for office, and to be elected to office than immigrants in other Western democracies, in part because voters in Canada do not discriminate against such candidates. Compared to their counterparts in other Western democracies, the children of immigrants have better educational outcomes, and while immigrants in all Western societies suffer from an “ethnic penalty” in translating their skills into jobs, the size of this ethnic penalty is lowest in Canada. Compared to residents of other Western democracies, Canadians are more likely to say that immigration is beneficial and less likely to have prejudiced views of Muslims. And whereas ethnic diversity has been shown to erode levels of trust and social capital in other countries, there appears to be a “Canadian exceptionalism” in this regard.”(2012)

3.2. Elements of Culture

Values and Beliefs

The first two elements of culture we will discuss, and perhaps the most crucial, are values and beliefs. Values are a culture’s standard for discerning desirable states in society (what is true, good, just, or beautiful). Values are deeply embedded and critical for transmitting and teaching a culture’s beliefs. Beliefs are the tenets or convictions that people hold to be true. Individuals in a society have specific beliefs, but they also share collective values. To illustrate the difference, North Americans commonly believe that anyone who works hard enough will be successful and wealthy. Underlying this belief is the value that wealth is good and desirable.

Values help shape a society by suggesting what is good and bad, beautiful and ugly, and what should be sought or avoided. Consider the value that North American culture places upon youth. Children represent innocence and purity, while a youthful adult appearance signifies sexuality. Shaped by this value, North Americans spend millions of dollars each year on cosmetic products and surgeries to look young and beautiful.

Sometimes the values of Canada and the United States are contrasted. Americans are said to have an individualistic culture, meaning people place a high value on individuality and independence. In contrast, Canadian culture is said to be more collectivist, meaning the welfare of the group and group relationships are primary values. As we will see below, Seymour Martin Lipset used these contrasts of values to explain why the two societies, which have common roots as British colonies, developed such different political institutions and cultures (Lipset, 1990).

Living up to a culture’s values can be difficult. It’s easy to value good health, but it’s hard to quit smoking. Marital monogamy is valued, but many spouses engage in infidelity. Cultural diversity and equal opportunities for all people are valued in Canada, yet the country’s highest political offices have been dominated by white men.

Values often suggest how people should behave, but they do not accurately reflect how people do behave. As we saw in Chapter 2, the classical sociologist Harriet Martineau made a basic distinction between what people say they believe and what they actually do, which are often at odds. Values portray an ideal culture, the standards society would like to embrace and live up to. But ideal culture differs from real culture, the way society actually is, based on what occurs and exists. In an ideal culture, there would be no traffic accidents, murders, poverty, or racial tension. But in real culture, police officers, lawmakers, educators, and social workers constantly strive to prevent or repair those accidents, crimes, and injustices. Teenagers are encouraged to value celibacy. However, the number of unplanned pregnancies among teens reveals that not only is the ideal hard to live up to, but that the value alone is not enough to spare teenagers from the potential consequences of having sex.

One way societies strive to put values into action is through rewards, sanctions, and punishments. When people observe the norms of society and uphold its values, they are often rewarded. A boy who helps an elderly woman board a bus may receive a smile and a “thank you.” A business manager who raises profit margins may receive a quarterly bonus. People sanction certain behaviours by giving their support, approval, or permission, or by instilling formal actions of disapproval and non-support. Sanctions are a form of social control, a way to encourage conformity to cultural norms. Sometimes people conform to norms in anticipation or expectation of positive sanctions: Good grades, for instance, may mean praise from parents and teachers.

When people go against a society’s values, they are punished. A boy who shoves an elderly woman aside to board the bus first may receive frowns or even a scolding from other passengers. A business manager who drives away customers will likely be fired. Breaking norms and rejecting values can lead to cultural sanctions such as earning a negative label — lazy, no-good bum — or to legal sanctions such as traffic tickets, fines, or imprisonment.

Values are not static; they vary across time and between groups as people evaluate, debate, and change collective societal beliefs. Values also vary from culture to culture. For example, cultures differ in their values about what kinds of physical closeness are appropriate in public. It is rare to see two male friends or coworkers holding hands in Canada where that behaviour often symbolizes romantic feelings. But in many nations, masculine physical intimacy is considered natural in public. A simple gesture, such as hand-holding, carries great symbolic differences across cultures.

Norms

So far, the examples in this chapter have often described how people are expected to behave in certain situations — for example, when buying food or boarding a bus. These examples describe the visible and invisible rules of conduct through which societies are structured, or what sociologists call norms. As opposed to values and beliefs which identify desirable states and convictions about how things are, a norm is a generally accepted way of doing things. Norms define how to behave in accordance with what a society has defined as good, right, and important, and most members of the society adhere to them because their violation invokes some degree of sanction. They define the rules that govern behaviour.

Formal norms are established, written rules. They are behaviours worked out and agreed upon in order to suit and serve most people. Laws are formal norms, but so are employee manuals, college entrance exam requirements, and no running at swimming pools. Formal norms are the most specific and clearly stated of the various types of norms, and the most strictly enforced. But even formal norms are enforced to varying degrees, reflected in cultural values.

For example, money is highly valued in North America, so monetary crimes are punished. It is against the law to rob a bank, and banks go to great lengths to prevent such crimes. People safeguard valuable possessions and install anti-theft devices to protect homes and cars. Until recently, a less strictly enforced social norm was driving while intoxicated. While it is against the law to drive drunk, drinking is for the most part an acceptable social behaviour. Though there have been laws in Canada to punish drunk driving since 1921, there were few systems in place to prevent the crime until quite recently. These examples show a range of enforcement in formal norms.

There are plenty of formal norms, but the list of informal norms — casual behaviours that are generally and widely conformed to — is longer. People learn informal norms by observation, imitation, and general socialization. Some informal norms are taught directly — “kiss your Aunt Edna” or “use your napkin” — while others are learned by observation, including observations of the consequences when someone else violates a norm. Children learn quickly that picking your nose is subject to ridicule when they see someone shamed for it by other children. Although informal norms define personal interactions, they extend into other systems as well. Think back to the discussion of fast food restaurants at the beginning of this chapter. In Canada, there are informal norms regarding behaviour at these restaurants. Customers line up to order their food, and leave when they are done. They do not sit down at a table with strangers, sing loudly as they prepare their condiments, or nap in a booth. Most people do not commit even benign breaches of informal norms. Informal norms dictate appropriate behaviours without the need of written rules.

Making Connections: Sociological Research

Breaching Experiments

Sociologist Harold Garfinkel (1917-2011) studied people’s customs in order to find out how tacit and often unconscious societal rules and norms not only influenced behaviour but enabled the social order to exist (Weber, 2011). Like the symbolic interactionists, he believed that members of society together create a social order. He noted, however, that people often draw on inferred knowledge and unspoken agreements to do so. His resulting book, Studies in Ethnomethodology (1967), discusses the underlying assumptions that people use to create “accounts” or stories that enable them to make sense of the world.

One of his research methods was known as a breaching experiment. His breaching experiments tested sociological concepts of social norms and conformity. In a breaching experiment, the researcher purposely breaks a social norm or behaves in a socially awkward manner. The participants are not aware an experiment is in progress. If the breach is successful, however, these innocent bystanders will respond in some way. For example, he had his students go into local shops and begin to barter with the sales clerks for fixed price goods. “This says $14.99, but I’ll give you $10 for it.” Often the clerks were shocked or flustered. This breach reveals the unspoken convention in North America that the amount given on the price tag is the price. It also breaks a number of other conventions which seek to make commercial transactions as efficient and impersonal as possible. In another example, he had his students respond to the casual greeting, “How are you?” with a detailed and elaborate description of their state of health and well-being. The point of the experiments was not that the experimenter would simply act obnoxiously or weird in public. Rather, the point is to deviate from a specific social norm in a small way, to subtly break some form of social etiquette, and see what happens.

To conduct his ethnomethodology, Garfinkel deliberately imposed strange behaviours on unknowing people. Then he would observe their responses. He suspected that odd behaviours would shatter conventional expectations, but he was not sure how. He set up, for example, a simple game of tic-tac-toe. One player was asked beforehand not to mark Xs and Os in the boxes but on the lines dividing the spaces instead. The other player, in the dark about the study, was flabbergasted and did not know how to continue. The reactions of outrage, anger, puzzlement, or other emotions illustrated the deep level at which unspoken social norms constitute social life.

There are many rules about speaking with strangers in public. It is okay to tell a woman you like her shoes. It is not okay to ask if you can try them on. It is okay to stand in line behind someone at the ATM. It is not okay to look over their shoulder as they make the transaction. It is okay to sit beside someone on a crowded bus. It is weird to sit beside a stranger in a half-empty bus.

For some breaches, the researcher directly engages with innocent bystanders. An experimenter might strike up a conversation in a public bathroom, where it’s common to respect each other’s privacy so fiercely as to ignore other people’s presence. In a grocery store, an experimenter might take a food item out of another person’s grocery cart, saying, “That looks good! I think I’ll try it.” An experimenter might sit down at a table with others in a fast food restaurant, or follow someone around a museum, studying the same paintings. In those cases, the bystanders are pressured to respond, and their discomfort illustrates how much we depend on social norms. These cultural norms play an important role. They let us know how to behave around each other and how to feel comfortable in our community, but they are not necessarily rational. Why should we not talk to someone in a public bathroom, or haggle over the price of a good in a store? Breaching experiments uncover and explore the many unwritten social rules we live by. They indicate the degree to which the world we live in is fragile, arbitrary and ritualistic; socially structured by deep, silent, tacit agreements with others of which we are frequently only dimly aware.

Folkways, Mores, and Taboos

Norms may be further classified as mores, folkways, or taboos. Mores (pronounced mor–ays) are norms that embody the moral views and principles of a group. They are based on social requirements. Violating them can have serious consequences. The strongest mores are legally protected with laws or other formal norms. In Canada, for instance, murder is considered immoral, and it is punishable by law (a formal norm). More often, mores are judged and guarded by public sentiment (an informal norm). People who violate mores are seen as shameful. They can even be shunned or banned from some groups. The mores of the Canadian school system require that a student’s writing be in the student’s own words or else the student should use special stylistic forms such as quotation marks and a system of citation, like MLA (Modern Language Association) style, for crediting the words to other writers. Writing another person’s words as if they are one’s own has a name: plagiarism. The consequences for violating this norm are severe, and can even result in expulsion.

Unlike mores, folkways are norms without any moral underpinnings. They are based on social preferences. Folkways direct appropriate behaviour in the day-to-day practices and expressions of a culture. Folkways indicate whether to shake hands or kiss on the cheek when greeting another person. They specify whether to wear a tie and a blazer or a T-shirt and sandals to an event. In Canada, women can smile and say hello to men on the street. In Egypt, it is not acceptable. In northern Europe, it is fine for people to go into a sauna or hot tub naked. Often in North America, it is not. An opinion poll that asked Canadian women what they felt would end a relationship after a first date showed that women in British Columbia were pickier than women in the rest of the country (Times Colonist, 2014). First date deal breakers included poor hygiene (82 percent), being distracted by a mobile device (74 percent), talking about sexual history and being rude to waiters (72 percent), and eating with one’s mouth open (60 percent). All of these examples illustrate breaking informal rules, which are not serious enough to be called mores, but are serious enough to terminate a relationship before it has begun. Folkways might be small manners, but they are by no means trivial.

Taboos refer to actions which are strongly forbidden by deeply held sacred or moral beliefs. They are the strongest and most deeply held norms. Their transgression evokes revulsion and severe punishment. In its original use taboo referred to being “consecrated, inviolable, forbidden, unclean, or cursed” (Cook & King, 1784). There was a clear supernatural context for the prohibition; the act offended the gods or ancestors, and evoked their retribution. In secular contexts, taboos refer to powerful moral prohibitions that protect what are regarded as inviolable bonds between people. Incest, pedophilia, and patricide or matricide are taboos.

Many mores, folkways, and taboos are taken for granted in everyday life. People need to act without thinking to get seamlessly through daily routines; we can not stop and analyze every action (Sumner, 1906). The different levels of norm enable the “ongoing concerting and coordinating of individuals’ activities” as Dorothy Smith put it (1999). These different levels of norm help people negotiate their daily life within a given culture and as such their study is crucial for understanding the distinctions between different cultures.

Symbols and Language

Humans, consciously and subconsciously, are always striving to make sense of their surrounding world. Symbols — such as gestures, signs, objects, signals, and words — are tangible marks that stand in for or represent something else. Symbols provide clues to understanding the underlying experiences, statuses, states, and ideas they express. They convey recognizable meanings that are shared by societies. In the words of George Herbert Mead:

Our symbols are universal. You cannot say anything that is absolutely particular, anything you say that has any meaning at all is universal. (Mind, Self and Society, 1934)

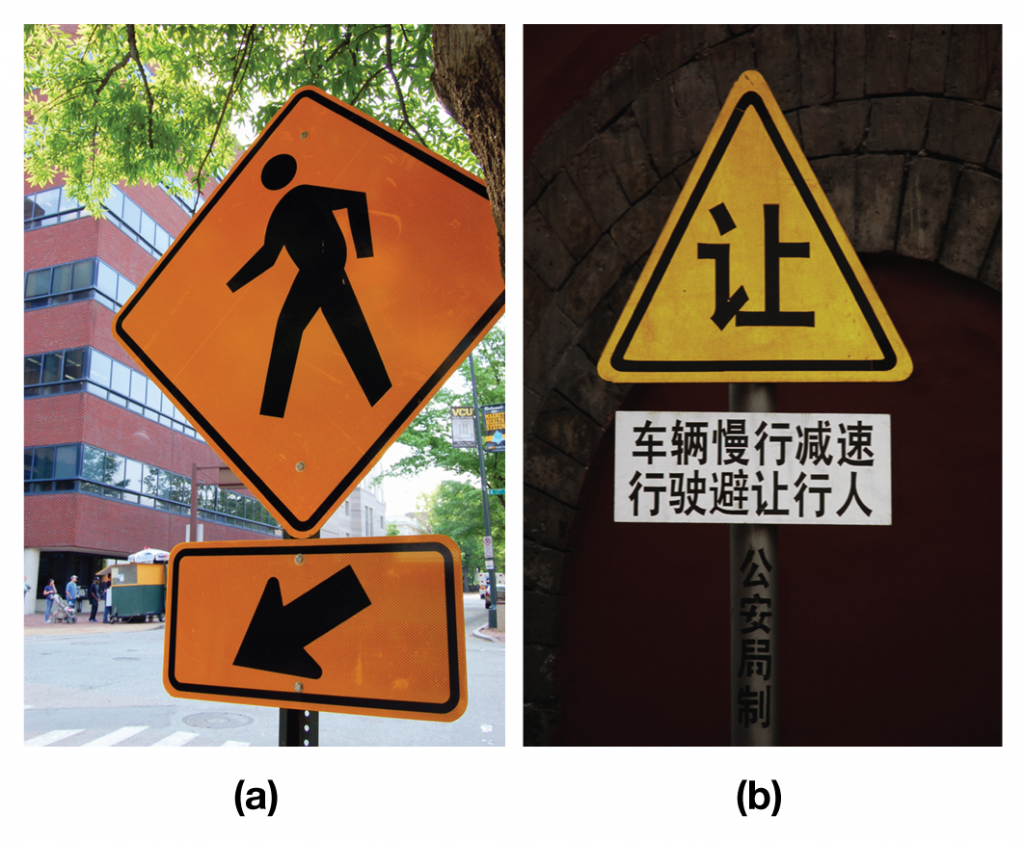

The world is filled with symbols. Sports uniforms, company logos, and traffic signs are symbols. In some cultures, a gold ring is a symbol of marriage. Some symbols are highly functional; stop signs, for instance, provide useful instruction. As physical objects they belong to material culture, but because they function as symbols, they also convey nonmaterial cultural meanings. Some symbols are only valuable in what they represent. Trophies, blue ribbons, or gold medals, for example, serve no purpose other than to represent accomplishments. Many objects have both material and nonmaterial symbolic value.

A police officer’s badge and uniform are symbols of authority and law enforcement. The sight of a police officer in uniform or in a police car triggers reassurance in some citizens but annoyance, fear, or anger in others.

It’s easy to take symbols for granted. Few people challenge or even think about the signs on the doors of public restrooms, but the figures on the signs are more than just symbols that tell men and women which restroom to use. They also uphold the value, in North America, that public restrooms should be gender exclusive. Even though stalls are relatively private, it is still somewhat uncommon to encounter unisex bathrooms.

Symbols often get noticed when they are used out of context. Used unconventionally, symbols convey strong messages. A stop sign on the door of a corporation makes a political statement, as does a camouflage military jacket worn in an antiwar protest. Together, the semaphore signals for “N” and “D” represent nuclear disarmament and form the well-known peace sign (Westcott, 2008). Internet memes — images that spread from person to person through reposting — often adopt the tactics of detournement or misappropriation used by the French Situationists of the 1950s and 1960s. The Situationists sought to subvert media and political messages by altering them slightly — “detouring” or hijacking them — in order to defamiliarize familiar messages, signs, and symbols. An ordinary image of a cat combined with the grammatically-challenged caption “I Can Has Cheezburger?” spawned the internet phenomenon lolcats because of the funny, nonsensical nature of its non sequitur message. An image of former Prime Minister Stephen Harper in a folksy sweater holding a cute cat was altered to show him holding an oily duck instead; this is a detournement with a political message.

Even the destruction of symbols is symbolic. Effigies representing public figures are beaten to demonstrate anger at certain leaders. In 1989, crowds tore down the Berlin Wall, a decades-old symbol of the division between East and West Germany, or between communism and capitalism.

While different cultures have varying systems of symbols, there is one that is common to all: the use of language. Language is a symbolic system through which people communicate and through which culture is transmitted. Some languages contain a system of symbols used for written communication, while others rely only on spoken communication and nonverbal actions.

Societies often share a single language, and many languages contain the same basic elements. An alphabet is a written system made of symbolic shapes that refer to spoken sounds. Taken together, these symbols convey specific meanings. The English alphabet uses a combination of 26 letters to create words; these 26 letters make up over 600,000 recognized English words (Oxford English Dictionary, 2011).

Rules for speaking and writing vary even within cultures, most notably by region. Do you refer to a can of carbonated liquid as a soda, pop, or soft drink? Is a household entertainment room a family room, rec room, or den? When leaving a restaurant, do you ask your server for the cheque, the ticket, l’addition, or the bill?

Language is constantly evolving as societies create new ideas. In this age of technology, people have adapted almost instantly to new nouns such as email and internet, and verbs such as download, text, and blog. Twenty years ago, the general public would have considered these nonsense words.

Even while it constantly evolves, language continues to shape our reality. This insight was established in the 1920s by two linguists, Edward Sapir and Benjamin Whorf. They believed that reality is culturally determined, and that any interpretation of reality is based on a society’s language. To prove this point, the sociologists argued that every language has words or expressions specific to that language. In Canada, for example, the number 13 is associated with bad luck. In Japan, however, the number four is considered unlucky, since it is pronounced similarly to the Japanese word for death.

The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis is based on the idea that people experience their world through their language and that they, therefore, understand the world through the culture embedded in their language. The hypothesis, which has also been called linguistic relativity, states that we initially develop language to express concepts that emerge from our experience of the world, but afterwards language comes back to shape our experience of the world (Swoyer, 2003). Studies have shown, for instance, that unless people have access to the word “ambivalent,” they do not recognize an experience of uncertainty due to conflicting positive and negative feelings about one issue. If a person cannot describe the experience, the person cannot have the experience.

Similarly, in Wade Davis’ (2007) discussion about the ethnosphere — the sum total of “ways of thinking, ways of being, and ways of orienting oneself on the earth” — that we began the chapter with, each language is understood to be more than just a set of symbols and linguistic rules. Each language is an archive of a culture’s unique cosmology, wisdom, ecological knowledge, rituals, beliefs and norms. Each contributes its unique solution to the question of what it means to be human to the ethnosphere. The compilers of Ethnologue estimate that currently 7,105 languages are used in the world (Lewis et al., 2013). This would suggest that there are at least 7,105 distinct cultural contexts through which humans interpret and experience the world. The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis would suggest that their worlds differ to the degree that their languages differ. However Davis notes that today half of the world’s languages are no longer being passed down to children. When languages die out or fail to be passed on to subsequent generations, whole ways of knowing and being in the world die out with them and the ethnosphere is diminished.

Making Connections: Sociology in the Real World

Is Canada Bilingual?

In the 1960s it became clear that the federal government needed to develop a bilingual language policy to integrate French Canadians into the national identity and prevent their further alienation. The Royal Commission on Bilingualism and Biculturalism (1965) recommended establishing official bilingualism within the federal government. As a result, the Official Languages Act became law in 1969 and established both English and French as the official languages of the federal government and federal institutions such as the courts. Pierre Elliott Trudeau’s governments of the late 1960s and early 1970s had an even broader ambition: to make Canada itself bilingual. Not only would Canadians be able to access government services in either French or English, no matter where they were in the country, but also receive French or English education. The entire country would be home for both French or English speakers (McRoberts, 1997).

However, in the 1971 census 67 percent of Canadians spoke English most often at home, while only 26 percent spoke French at home and most of these were in Quebec. Approximately 13 percent of Canadians could maintain a conversation in both languages (Statistics Canada, 2007). Outside Quebec, the province with the highest proportion of people who spoke French at home was New Brunswick at 31.4 percent. The next highest were Ontario at 4.6 percent and Manitoba at 4 percent. In British Columbia, only 0.5 percent of the population spoke French at home. French speakers had widely settled Canada, but French speaking outside Quebec had lost ground since Confederation because of the higher rates of anglophone immigrants, the assimilation of francophones, and the lack of French-speaking institutions outside Quebec (McRoberts, 1997). It seemed even in 1971 that the ideal of creating a bilingual nation was unlikely and unrealistic.

What has happened to the concept of bilingualism over the last 40 years? According to the 2011 census, 58 percent of the Canadian population spoke English at home, while only 18.2 percent spoke French at home. Proportionately the number of both English and French speakers has actually decreased since the introduction of the Official Languages Act in 1969. On the other hand, the number of people who can maintain a conversation in both official languages has increased to 17.5 percent from 13 percent (Statistics Canada, 2007). However, the most significant linguistic change in Canada has not been French-English bilingualism, but the growth in the use of languages other than French and English. In a sense, what has happened is that the shifting cultural composition of Canada has rendered the goal of a bilingual nation anachronistic.

Today it would be more accurate to speak of Canada as a multilingual nation. One-fifth of Canadians speak a language other than French or English at home; 11.5 percent report speaking English and a language other than French, and 1.3 percent report speaking French and a language other than English. In Toronto, 32.2 percent of the population speak a language other than French and English at home: 8.8 percent speak Cantonese, 8 percent speak Punjabi, 7 percent speak an unspecified dialect of Chinese, 5.9 percent speak Urdu, and 5.7 percent speak Tamil. In Greater Vancouver, 31 percent of the population speak a language other than French and English at home: 17.7 percent of whom speak Punjabi, followed by 16.0 percent who speak Cantonese, 12.2 percent who speak an unspecified dialect of Chinese, 11.8 percent who speak Mandarin, and 6.7 percent who speak Philippine Tagalog.