3 Celebrating diversity: Focusing on inclusion

Lindy Abawi

So, what can we do as teachers to prepare ourselves to be social justice advocates and teachers whose inclusive classrooms embrace and honour diversity?

Key Learnings

- The Australian demographic has been changing dramatically resulting in an increasingly diverse population.

- Every individual is shaped and influenced by multiple factors which add to the rich tapestry of a school and community.

- Inclusion involves acceptance and catering for the needs of all learners.

- At the heart of any inclusive school is the creation of a culture where each individual is accepted and embraced for who and what they bring to the learning space.

Introduction

As teachers, we are privileged to have the opportunity to work in diverse contexts and with diverse groups and individuals. The richness and opportunities within today’s classrooms provide a wealth of opportunities to learn from, and with our students, parents, community and colleagues. By sharing perspectives and histories that may be unfamiliar to us and to others, opportunities are created that must be embraced in order to break down the many social injustices that still exist, and which limit the opportunities of students to fulfil their full potential.

In 2013, then 16 year old Pakistani activist, Malala Yousafzai spoke at an international assembly and said “ thousands of people have been killed by the terrorists and millions have been injured. I am just one of them. So here I stand, one girl among many. I speak not for myself, but for those without a voice that can be heard. Those who have fought for their rights. Their right to live in peace. Their right to be treated with dignity. Their right to equality of opportunity. The right to be educated” (Malala Yousafzai Quote, 2013). As teachers it is our moral obligation to do no less.

Many of our most marginalised students and families find it difficult to be heard and we can be their voice and advocate for inclusion and equity. The Melbourne Declaration on Educational Goals for Young Australians (2008) clearly states our moral and legal obligation to provide opportunities for all students to succeed, as do the various Australian state jurisdiction Anti-Discrimination Acts. As a consequence, teaching should, and can be an activist profession (Sachs, 2003) where we can seek to make a difference in the lives of the children and young people that we teach. To achieve this, educators must also be continual learners, seeking to know and understand their students and their education setting communities, in order to be able to provide targeted support, because “learning in schools occurs when meaning making takes place. A sociocultural approach to understanding how learning takes place is built on cognitively explicating the relationships between actions and understandings” (Abawi, 2013, p. 91).

In this chapter we seek to develop the reader’s understandings by exploring the concepts of diversity and inclusion in order to prepare ourselves for action, as teachers who are social justice advocates, and teachers whose inclusive classrooms embrace and honour diversity.

understanding diversity

A snapshot of our nation

There is an increasing emphasis in schools, on understanding and catering for the diversity of learners in our classrooms, and rightly so. Consequently, let’s examine what diversity looks like within a contemporary Australian landscape.

The demography of Australia has been changing dramatically, with increasing evidence of a nation rich in diversity. According to statistics from the 2016 Australian National Census, 33.3% of Australians were born overseas, and a further 34.4% of people had both parents born overseas (Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), 2018). In 2016, 82% of the overseas-born population lived in capital cities (refer to Table 3.1) (Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), 2018). Disturbingly, in 2012, 2.55 million people (13.9%) were living below the poverty line, after taking account of their housing costs, and 603, 000 children (17.7% of all children) were living below the poverty line (Australian Council of Social Service[ACOSS], 2012).

The 2016 National Census identified that the resident Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population of Australia was 649 171 people, 2.8% of the total Australian population counted, up from 2.5 per cent in 2011, and 2.3 per cent in 2006 (ABS, 2018). Of the Australian states and territories, the largest populations of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians live in New South Wales and Queensland. However, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians comprised 30% of the population of the Northern Territory, the highest proportion of any state or territory.

Between 2001 and 2011, the number of people reporting a non-Christian faith increased considerably, from around 0.9 million to 1.5 million, accounting for 7.2% of the total population in 2011 (up from 4.9% in 2001). The most common non-Christian religions in 2011 were Buddhism (accounting for 2.5% of the population), Islam (2.2%) and Hinduism (1.3%). Of these, Hinduism had experienced the fastest growth since 2001, increasing by 189% to 275,500, followed by Islam (increased by 69% to 476,300) and Buddhism (increased by 48% to 529,000 people) (ABS, 2011). The 2015 Survey of Disability, Ageing and Carers (SDAC) identified that almost one in five Australians reported living with disability (18.3% or 4.3 million people) (ABS, 2015).

As a result of the impact of the diversity on the Australian population, many educators struggle to meet the needs of learners within education settings composed of students from culturally, ethnically and linguistically diverse backgrounds, in addition to students with varying levels of ability, children raised in poverty and the dynamics of alternative family structures (Sands, Kozlwak & French, 2000).

Reflection

- What does an increased diversity of demographic mean for your classroom / education setting or organisation?

- What does this mean for your teaching practice?

- How well prepared are you for this level of diversity?

reframing diversity

What does the term diversity mean?

Certainly, these statistics are significant in understanding the diversity of our nation, but it is important to understand diversity, not just in terms of groups or labels but rather in terms of individuality. As we know each and everyone of us is unique and different in many varied ways, with our difference from each other influenced by a collection of diverse genetic and environmental factors (Ashman, 2015).

As such, the term diversity then includes more than socio-economic, cultural, ethnic and linguistic differences. It also includes differences arising from gender and sexual orientation, and includes differences in tastes, preferences and communication styles. Appropriately, the term diversity also includes the differences in the skills and capacities that learners bring to education settings (Sands et al., 2000). Consider also the diverse learning styles and preferences of students, and the role that motivation, cognitive load, and mental ability have on students, and how they also add to the diversity of any learning group.

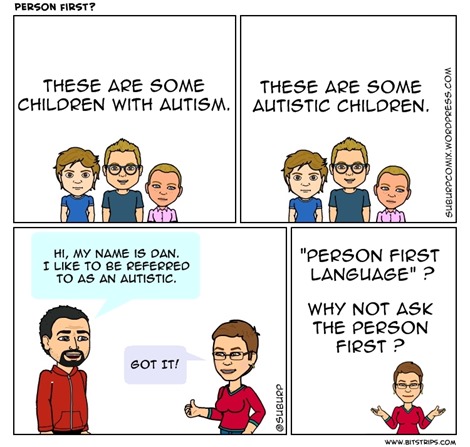

Often in education settings, we group students by labels. We talk about catering for gifted and talented learners or exceptional learners, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, students for whom English is an Additional Language or Dialect [EAL/D], autistic students, or even group a diverse range of disabilities and learning impairments into one group such as students with disabilities.

The danger with such groupings is that we may then think of each of these groups homogeneously with a ‘one size fits all’ mentality, and this impacts on how we plan the learning and cater for diversity in our classrooms. When individuals appear to have some similar characteristics, they tend to be labelled by others and themselves (Sands et al., 2000). For example, it is not uncommon to refer to the ‘nerds’ at school or the ‘sporty types’ as collective groups. Likewise, classifying is a common practice in health, education, and business. For example, in health, patients are categorised by conditions [heart, cancer etc.].

In education, and in life, we tend to label in multiple ways, and in doing so we sometimes risk assuming that individuals within a category have all the same needs and all learn the same way. This is not always the case. Such labelling can also result in deficit thinking, and in fact result in lower expectations and/or create stereotyping.

Consider the graphic representation in Figure 3.4.

It is these variables and varied factors that contribute to each of us as individuals, and are what we add to the rich tapestry of education setting and its community.

In our classrooms, we have young people who have similarities and differences in:

• Philosophy – points of view , perspective, religion and experiences.

• Physiology – genetics, cognitive and physical ability and mental, physical health and wellbeing.

• Identity- race, gender, ethnicity, nationality, age and family.

• Demographics – socio-economic, citizenship and location.

• Learning preferences – types of intelligences or visual, auditory or kinesthetic learning styles (VAK).

family diversity

One of the most powerful activities in getting to know your students is to ask them to draw a visual representation of their family. This will give you great insight into the diversity of family structures. These diverse structures challenge teachers to consider the fact that many children do not live in what is often described as the traditional family – Mum, Dad, children and the pets. Often in Western cultures, and portrayed this way in the media, this family is seen as the most desirable type of family. Given this, children who do not live in a family that fits this profile and promoted norm can grow up with a view that their family is not normal.

What is acceptable in one family and culture may not be in another. For example, in some cultures, polygamy is common. There are rules in some families, for example, where one member is considered the person in charge. In patriarchal families, the family is ruled by men – they make the important decisions – whereas the opposite is the case for matriarchal families. Families are also very fluid. Partners may change through death or divorce and be reconstituted with further marriage or relationships (Cohen et al., 2007).

So, let’s consider the types of diversity that can exist in learners’ lives.

• Organisational Diversity

Different kinds of family compositions – single parent, blended, reconstituted or fostered.

• Cultural Diversity

For example, the Kibbutz in Israel where families live together communally; arranged marriages in India; or stem families in China (three or more generations live together).

• Social Class Diversity

Different access to material and economic resources.

• Life Cycle Diversity

Different stages of development – a family in early stages of development would have young children (consider the fact that sleep may be interrupted on a regular basis).

• Cohort Diversity

Each period is likely to impact on families in different ways: for example, the radical social change that occurs as a result of war.

(Adapted from Cohen et al., 2007).

the cultural interface in an inclusive school

Considering the diverse cultural backgrounds of the students in our education settings and the families who support them, it is worth reflecting on ways to see if we can bridge gaps in understanding and knowledge, in areas where we, as educators, may be lacking. Nakata (2006) suggests that educators conceptualise the cross cultural space, not in terms of perceived opposites and differences, but in terms of knowledge systems composed of sets of complex, layered concepts, theories and meanings. Nakata’s work has been central to bringing non-Indigenous Australians and Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people toward a closer understanding, respect and appreciation of the richness and value in diversity. Too often within education settings, a dominant ‘white’ perspective on the world is most evident, and this can have ongoing consequences for children and young people who find it difficult to see themselves as having a valued place within a ‘Western’ education system.It is important then as teachers, especially for those of us who are non-Indigenous teachers, to carefully consider how we can be a part of the struggle to address the lies and omissions that shape Australian history. We must proactively work against racism in any form. To help us in this mission we need to construct counter-discourses and utilise ways of thinking and pedagogical practices that engage and challenge learners to think differently and to dig deeper into their own consciousness and experiences and embrace the diversity of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture and peoples.

The following statistics from the Closing the Gap, Prime Minister’s Report, 2015 were based on standardised proportions and indicated that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were: twice as likely as non-Indigenous people to have asthma (rate ratio of 1.9); more likely than non-Indigenous people to have diseases of the ear and/or hearing problems (rate ratio of 1.3); more likely than non-Indigenous people to have heart or circulatory diseases (rate ratio of 1.2); and three times as likely as non-Indigenous people to have diabetes/high sugar levels (rate ratio of 3.3). Similar statistics portray an equally negative discourse about educational outcomes. However, this type of deficit discourse presents one view only and has been criticised for the language, cultural overtones and assumptions made.

Click and explore the concepts of knowledge, power and voice, and whose voices are often silenced.

Watch

A role play filmed in 2017, conceptualised by USQ’s Indigenous Curriculum and Pedagogy Consultant, Megan Cooper, and enacted by a number of academics and friends of USQ, including Megan herself who introduces the scenario.

Reflection

As you engage with each segment ask yourself the following the questions:

• Whose points of view resonate with yours?

• Which are the dominant voices? Why? Should they be?

• How is ‘knowledge’ positioned within the meeting? Whose knowledge counts?

How would you explain the power relationships between the groups presented in the video? Consider the concepts of ‘Power over’, ‘Power with’ and ‘Power to’ and how a deficit discourse creates ongoing inequity resulting in low expectations and the framing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders as victims. What other sections of our society are being victimised? It is so simple to stereotype learners and make generalisations. Is there not also a similar deficit discourse about refugees and Muslims for example?

Indigenous Pedagogical Framework – 8 Ways Pedagogy

An Indigenous Pedagogical Framework originating from research with Australian Indigenous communities in Northern New South Wales, called the 8 Ways Pedagogy provides teachers, and others, with one set of culturally inclusive lenses with which to view the world and also to use when planning activities.

Australian Curriculum

Certainly there have been efforts made in recent times to ensure that Australian Indigenous peoples and their knowledge systems and beliefs are being valued within the Australian educational system. The most significant of these relates to the advent of the Australian Curriculum. The Australian Curriculum was introduced in 2008 with an aim to ensure an equal curriculum for all Australian students (Australian Government, 2008). A big plus for the curriculum is the inclusion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander histories and cultures as a cross-curriculum priority, meaning that the Indigenous perspective is embedded throughout the eight learning areas of the Australian Curriculum. ‘Country/place’, ‘culture’ and ‘people’ and ‘identity within the living community’ are embedded in the curriculum, as well as the “development of knowledge about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples’ law, languages, dialects and literacies” (Australian Curriculum Assessment and Reporting Authority [ACARA], 2018). Themes of celebration of strength and resilience “against the historic and contemporary impacts of colonisation” (ACARA, 2018) are explored.

The Australian curriculum also acknowledges that Indigenous students’ first language may be Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander dialect and literacy will therefore be more complex to learn. It recognises the diversity of sociocultural, linguistic and cultural factors of all Indigenous learners and the personalised learning needs they may require to meet the curriculum. Continuing to be critical about the curriculum is important to ensure anti-racism curriculum is implemented. The inclusion of Indigenous perspective in the Australian Curriculum was not difficult (Nakata, 2011). The Australian Curriculum developers ensured coherence with policies and practices at a system level (Schleicher, 2017), there was content rigour (Morris & Burgess, 2018) and curricula were developed with Indigenous authors (Parkinson & Jones, 2018). However, the education setting administration needs to be committed to implementation of the curriculum and teachers need to deliver content with an understanding of the dispossession and struggle experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders and the continuing effect of colonisation on their lives (Schleicher, 2017).

Leading a Culturally respectful school

Schleicher (2017) identified that in education settings where Indigenous students had high rates of achievement, the results of that success could be generally attributed to a highly effective and committed principal who exhibited a ‘do whatever it takes’ approach that ensured that Indigenous students attended school, engaged in learning and made good progress. Effective principals set high expectations for teachers and take responsibility for monitoring student performance.

Under such leadership, resources are provided to ensure culturally sensitive teaching . Extra support is provided to support individuals who require more help. Cultural competence training is delivered to assist educators to understand cultural perspectives of Indigenous peoples and to identify their own underlying bias (Riley & Pidgeon, 2018). Professional development to understand Aboriginal specific language development and cultural norms is provided to further assist educators’ understanding Indigenous learners (Schleicher, 2017). Approaches in such schools tend towards a ‘whole-of-child’ perspective that placed students’ overall wellbeing as a key priority, ensured indigenous students progressed academically, expected progress was met and that any necessary interventions were put in place in a timely manner (Schleicher, 2017).

Principals who are committed to developing best possible outcomes for Indigenous families, treat families with respect (Schleicher, 2017). They acknowledge and address the negative impact and trauma that Indigenous people will have experienced with education systems, which may cause Indigenous families to resist the traditional school culture. Culturally responsive content is addressed in a holistic manner and a sense of belonging is created so students want to attend school regularly (Bodkin-Andrews & Carlson, 2016).

Teacher perspectives

Many of the teachers who are delivering the Australian Curriculum, were exposed to only one side of the story in their own education (Gilbey, 2018). Teachers may be ignorant of the Indigenous perspective, have racist beliefs acquired from their own knowledge and upbringing or anti-racist and therefore struggle to support ideals striving to support all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders well-being and education (Gilbey, 2018). Teachers may not have had Indigenous perspective courses in their Higher Education courses, or may not have worked in schools with Indigenous students (Slee, 2011).

Developing a culture of inclusion for Indigenous students will only occur when the curriculum addresses the indigenous perspective, teachers create respectful trusting relationships with Indigenous students and have high expectations about Indigenous students (Riley & Pidgeon, 2018). According to Schleicher (2017) Indigenous learners said they felt supported when:

- their teachers took an interest in them;

- cared about them and who they were as Indigenous people;

- expected them to succeed in their learning; and

assisted them to learn about their cultures, histories and language/s.

The importance of Indigenous and non-Indigenous people working together to understand cultural bias in the curriculum has been espoused by Nakata (2011). Nakata argues non-indigenous people can never fully understand the dispossession, trauma and racism experienced by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders as a result of colonialism, but they can listen and understand the impact on their identity (Nakata, 2011). Using this knowledge, local community members can create partnerships with schools to ensure an anti-racist education is established and maintained.

Watch

Engaging the community within Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander early education

socio-economic diversity

There is a significant amount of literature, research and debate about the impact of socio-economic disadvantage on educational outcomes for children. The following factors are considered to contribute to socio-economic disadvantage and add to the diversity of individual, groups and communities.

1. Poverty

Measuring disadvantage in wealthy countries is calculated by considering the proportion of the population living below what is referred to as the ‘poverty line’. Poverty lines are mostly based on the after-tax income of households. According to the Australian Council of Social Service (ACOSS) Report on Poverty (2012), single parents, females, adults born in countries where English is not the main language, people with a disability, the unemployed, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are at higher risk of poverty and at greater risk of social security being the main source of income.

2. Deprivation

Another measure of disadvantage is ‘deprivation’. Deprivation is measured by the proportion of households lacking items which the majority consider as essential. Saunders and Wong (2012) identified that there were six key categories of essential needs:

1. the need for basic materials;

2. the need for good health;

3. the need for accommodation;

4. the need for social interaction and functioning;

5. the need for safety and reduced risk; and

6. the need for children’s needs to be met.

3. Social Exclusion

There are many definitions of social exclusion.

- Lack of connectedness.

- An inability to participate in key activities in the local community because of a lack of access to resources required.

- An inability to access institutions, services and social networks.

- Negative impact on quality of life and wellbeing.

However, it is important to note that individuals may experience social exclusion without necessarily living below the poverty line. Similarly, individuals may experience levels of deprivation and be above the poverty line.

There have been a number of studies linking persistent socioeconomic disadvantage to negative impact on educational and life outcomes. Feruson, Bovaird and Mueller (2007) describe four factors that impact on education and life: 1) social functioning; 2) academic functioning; 3) chronic physical health problems; and 4) psychiatric disorders which can also significantly affect the school readiness of young children. Similarly, a longitudinal study by Duncan (1993) found that family income and poverty status correlated strongly with the cognitive development and behaviour of children. Having said this, there are also studies that question the strength of this correlation. Rothman (2003) refers to data from the Longitudinal Surveys of Australian Youth which found a decrease in the relationships between socio economic status and academic achievement between 1975 and 1995, although this was less evident between 1995 and 1998. These surveys analysed reading comprehension and mathematics performance data.

Without a doubt though, students living with socioeconomic disadvantage can feel a sense of social exclusion in schools. The impact of not being able to afford equipment, attend excursions, buy school photos and more, contributes to disengagement and social exclusion. We should not, however, assume that all students who live in disadvantaged situations are disengaged and feel social exclusion in educational settings. If this is not understood then again stereo-typing occurs. Payne’s (1995), A Framework for Understanding Poverty, has been used in teacher training and professional development activities for years, particularly in the United States but also in other countries, such as Australia. Recently this work has come under intense academic scrutiny for exactly the reason mentioned above (Gorski, 2012). The reasons for this are that broader systemic issues are ignored and stereotyping and the deficit perspectives at play are in fact theoretically ungrounded.

According to Lee and Burkam (2003) as cited by Gorski (2012), students labelled ‘at-risk’ who attend schools that combine rigorous curricula with learner-centred teaching achieve at higher levels and are less likely to drop out than their peers who experience lower-order instruction. All learners, including those from low socio-economic backgrounds learn best in schools where there are very high academic expectations for all students. Standards should never be based on socioeconomic status, nor should they be lowered in response to the socio-economic background of learners (Gorski, 2012)which clearly resonates with Paulo Freiere’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed first published in 1968.

factors adding to group diversity

Learning Styles

Learning styles describe how we approach different tasks as well as our different individual preferences and strengths in learning. We all process information and learn different skills in a variety of different ways as our brains are complex, and can make use of visual (seeing), auditory (hearing), kinesthetic (touching) and reflective (thinking) processes. As a consequence, learning styles also contribute to the diversity of a learning group, with a variety of preferences for learning evident in any one class group.

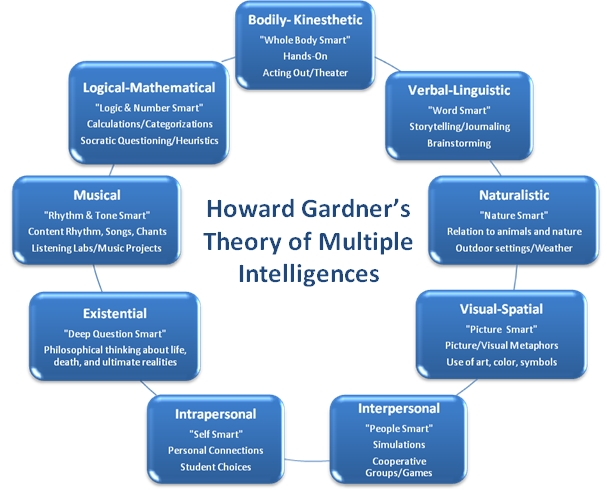

The Theory of Multiple Intelligences, developed by Howard Gardner (2006), proposed that individuals possess a number of autonomous intelligences, which individuals regularly draw on both individually and collectively, to create and solve problems that are relevant to the societies in which they live (Davis, Christodoulou, Seider & Gardner, 2011). The intelligences include: visual intelligence, linguistic (verbal) intelligence, logical-mathematical intelligence, spatial intelligence, interpersonal intelligence, intrapersonal intelligence, naturalistic intelligence, bodily-kinaesthetic intelligence, and musical intelligence. Over time Gardner built on these and added spiritual/existential and moral intelligences (refer to Figure 3.7).

Others question the validity of different learning styles theory and argue that the theory is a culturally biased way of understanding the varied ways in which learners learn (Peariso, 2008). Many critics describe the theory as being moralistic and overly focused on delivering a highly individualised child centred pedagogy rather than pedagogy that nurtures a broader, set of human attributes (Peariso, 2008).

Despite such criticisms, educators consider Howard Gardner’s (2006) Theory of Multiple Intelligences (Figure 3.7) and other learning styles theories to be useful ways of considering the diversity of learners in our classrooms. The important message to retain from any theory is that learners do learn differently and may well have very different learning preferences. Therefore, as teachers it is incumbent upon us to ensure that varied ways of learning and assessment of learning should be provided to students. Such activities need to be consciously chosen so as to cater to a student’s strengths whilst at other times building and consolidating areas that are challenging for them.

The Domains of Learning

Using labels, particularly for students with disabilities, does not always help teachers to plan effectively, make adjustments and select the most appropriate learning activities, and can sometimes result in, unintentionally, stereotyping a student. However, naming groups does serve a purpose when trying to pinpoint specialised needs. Anderson and Krathwohl’s (2001) revised work on Bloom’s Taxonomies devised four domains of learning that assist in understanding the needs of each learner: 1)the cognitive, 2) affective, 3) sensorimotor and 4)social domain.

In psychology, these concepts are often referred to as:

- the cognitive domain (knowledge);

- the psychomotor domain (skills);

- the affective domain (attitudes); and

- the psychosocial domain (social skills) (Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2016).

Sands et al., ( 2000) suggest that these domains do not stand alone, and instead are complex, interactive components of the whole person. Using the four domains of learning can assist in understanding the needs and characteristics of individuals and groups of learners.

understanding the individual

If we then consider an individual in terms of the four domains and varied learner preferences, then layer that with a person’s culture, ethnicity, gender, and socio-economic status, we have a better understanding of diversity. Diversity is something that all children, young people and adults have in common, both within individuals and across groups. In response to such diversity, it then becomes an essential responsibility of all educators and all those who support educators, that each and every individual’s diversity is built upon, that a belief is held that all individuals have the capacity to learn, and that educators uphold all individuals’ right to learn (Peters, 2007).

The Neurodiversity – each of us is special

The National Symposium on Neurodiversity (2011) proposed that Neurodiversity should be recognised and respected the same as any other human variation. Neurodiversity includes neurological difference such as Dyspraxia, Dyslexia, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, Dyscalculia, Autistic Spectrum, Tourette Syndrome. Listen to this simple explanation of Neurodiversity and then watch this brilliant young man explain the same thing in pictures – in Ryan’s Book of Brains.

accountability

As you would be aware it is important that teachers have knowledge of the relevant legislation that impacts on their legal and professional accountabilities. Diverse learners are protected by a suite of federal and state Acts which focus predominantly on age, gender, human rights, race and disability an include the following:

- Commonwealth Age Discrimination Act 2004. https://www.comlaw.gov.au/Series/C2004A01302

- Commonwealth Racial Discrimination Act 1975. https://www.comlaw.gov.au/Details/C2014C00014

- Commonwealth Sex Discrimination Act 1984. https://www.comlaw.gov.au/Series/C2004A02868

- Queensland Consolidated Acts: Anti-Discrimination Act 1991. http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/qld/consol_act/aa1991204/s7.html

- Commonwealth Disability Discrimination Act 1992. https://www.comlaw.gov.au/Series/C2004A04426

- Disability Standards for Education 2005.https://www.comlaw.gov.au/Details/F2005L00767/Download

Coupled with legislation, policy and procedure underpin the functioning of schools both state and non-state. For example, in Queensland’s Department of Education and Training (DET), there are a raft of policies/frameworks that relate to diversity and inclusion including:

- Inclusive Education Policy Statement

- Disability Policy

- Supporting Student Health and Wellbeing policy

- Students in Out-of-home Care Policy

- English as and Additional Language or Dialect Policy

- Capability Framework: Teaching Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander EAL/D Learners

- Learning and Wellbeing Framework

things to remember about diversity

It is important to remember that even though the research might indicate, for example, that Aboriginal students often work best in group work, we should never stereotype an individual and assume a ‘one size fits all’ mentality – after all group work is best for many different learners. Above all, we need to know our learners. For example, it is important to understand the ways of learning that work best for gifted students but be very careful not to assume that every gifted learner will learn that way because we need to consider other factors in their life, such as ethnicity, gender, health and family. We must also not assume that skills in one area are automatically translated into another.

understanding inclusion

definitions of inclusion

The Melbourne Declaration on Education Goals for Young Australians (Ministerial Council on Education, Employment, Training and Youth Affairs [MCEETYA], 2008) declared that “all Australian governments and all school sectors must provide all students with access to high-quality schooling that is free from discrimination based on gender, language, sexual orientation, pregnancy, culture, ethnicity, religion, health or disability, socioeconomic background or geographic location” (MCEETYA, 2008, p.7). Inclusion is therefore not a choice but an obligation.

What does the word inclusion mean?

There are numerous definitions of inclusion and inclusive education. Let’s consider some of the definitions and considerations. Ashman (2015) defines inclusion in terms of ‘acceptance’ and catering for the needs of all learners by making appropriate adjustments. The term inclusion describes the act of accepting a student completely – regardless of any difference, their impairments or their disability, within a regular class, with adjustments made to the learning program to ensure that every learner is fully engaged in all class activities (Ashman, 2015).

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation [UNESCO] Policy Guidelines on Inclusion in Education (2009), describes inclusion holistically by referring to inclusive education as a ‘process’ where by it is the system that needs to be inclusive: “Inclusive education is a process of strengthening the capacity of the education system to reach out to all learners, and can thus be understood as a key strategy to achieve (education for all)” (UNESCO, 2009, p. 8). The UNESCO guidelines also consider inclusion not only in terms of the right to participate in learning but also in terms of social acceptance so that children actually feel included, as do their families, in every relevant aspect of school life.

According to Hyde (2010), inclusion is about learning, social participation and enduring well-being, and is directly influenced by an individual’s ability to successfully access and engage in quality educational and social experiences. Hyde (2010) also refers to the importance of engagement when considering inclusion where engagement is the degree to which the student is attached emotionally, socially, cognitively and academically to the school.

Carter and Abawi (2018) developed the following definition “inclusion is defined as successfully meeting student learning needs regardless of culture, language, cognition, gender, gifts and talents, ability, or background” (p.2). They go on to say that “within the literature, definitions are blurred and ‘special needs’ are often referred to when exploring inclusion. ‘Special needs’ has been linked to disadvantage and disability, but we define special needs more broadly as the individual requirements of a person, and the provision for these specific differences can be considered as catering for special needs” (p. 2). What does inclusion mean to you?

segregation to inclusion – a brief history

Figure 3.9: Segregation to Inclusion

Figure 3.9: Segregation to Inclusion

Chronology of historical educational practice in Australia

The following chronology of education in Australia provides an outline of the major milestones and trends in the development of educational practices and the movement from segregation to inclusion.

1850’s

• During this period education few children from the working classes and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children engaged in education.

1860s and 70s

• Education Acts placed all primary education under one general and comprehensive system controlled by Boards of General Education.

1880s and 90s

• Free, secular and compulsory education in State schools .

• The ‘Blind, Deaf and Dumb’ became a focus with schools established to cater for vision and hearing impaired students.

1900s and 1910s

• Arguments proposed for universal secondary education.

1920s and 30s

• Rise of technical and domestic schools for the working class in order to meet the needs of a growing economy post World War 1.

• The first special classes were provided for ‘handicapped’ children.

• Classes for ‘backward’ children became ‘Opportunity Classes’.

• Education becomes compulsory for vision and hearing impaired children through the Blind, Deaf and Dumb Children Instruction Bill of 1924.

1950s

• The State Schools for ‘Spastic Children’ open.

• Separate schools were established for students with mild intellectual disabilities.

1960s

• Establishment of comprehensive high schools.

• Differentiation between government and non-government.

• Streaming between academic and vocational.

• Integration started to gain traction in some schools, although the prevalence of institutions and special schools continued.

• Opportunity schools contained large numbers of students with 2000 students placed in Queensland Opportunity schools in the 1960s.

1970s

• The Karmel Report had impact with a focus on educational inequality.

1980s

• Parental choice and diversity of schooling emerged.

• Compensatory funding for identified/targeted groups began to get traction.

• A growing culture of expectations of school and student performance.

1990s

• Education department policies began to focus on accommodating the diverse needs of students.

• A stronger focus on discrimination legislation emerged.

2000s –

• Schools viewed as corporate models with targets and performance indicators.

• Disability Standards for Education with a focus on inclusive school cultures.

What would you expect to see in an inclusive school?

• The student is part of the community.

• Schools make adjustments to fit the students.

• Acceptance.

• Fair treatment.

Unfortunately, some schools are less than inclusive. Right from the point when parents ask questions around enrolment and the first interview with the school Principal or Deputy takes place problems can start to arise. In the words of a District Support Officer:

Our schools [State Schools] can’t say no, but some make things seem very challenging … “oh … your child will be the only child like this in Year 3 so we don’t really have a structure where we could pull them out to do this, that or the other, so this is all we can do for them. (Abawi, 2015)

Although no student can be explicitly turned away from a school, it is certainly not unknown for the leadership team to suggest that a child with a particular need would be better catered for at another school. Parents feel that their child is unwelcome and rather than debate the issue they leave and try again. Not only is the child ‘excluded’ but so are the parents.

characteristics of inclusive schools

At the heart of any inclusive school is the creation of a culture where each individual is accepted and embraced for who and what they bring to the learning space. It is also about social justice and about enabling each individual to reach their full potential. In order to do this, we may have to set aside our pre-conceived norms and assumptions about a student’s ability, and build learning opportunities to challenge and extend by enabling engagement at every level.

Inclusive practice can be described as any type of practice or efforts made by educational settings where students and their parents and care givers are made to feel welcomed and valued. Within this practice it is implied that if a student’s participation becomes as issue as a result of disability, gender, behaviour, poverty, culture, refugee status or any other reason, then ever effort will be made not to establish special programs for individuals or groups, but instead to expand mainstream thinking, structures and practices so that all students are accommodated within the setting (Shaddock, Giorcelli & Smith , 2007).

Inclusive school communities:

- Uphold the rights of students.

- Value diversity.

- Ensure access and participation.

- Match pedagogy to student need.

- Share responsibility.

- Share decision making.

- Value parents/carers as partners.

However, Sands et al. (2000) note that creating an inclusive culture is not a simple task. Building and sustaining an inclusive culture requires the development of a sense of belonging, opportunities for meaningful participation, the fostering of positive alliances and affiliations, opportunities for collaboration and the provision of emotional and technical support for all members of the community.

Quality relationships – belonging and participation

Human beings have a fundamental need to belong and be accepted. Loneliness and isolation deeply affect many people at some stage in their lives. It was not all that long ago that segregation of diverse learners was evident in schools. For example, for many years special education services were provided to identified students in a ‘special education unit’, often an isolated place with minimal social and academic interaction with other students in the school. Although no malice was intended, students with disabilities were often systematically excluded from many educational settings and from many interactions that their peers would have typically experienced (Sands et al., 2000).

Every student in every classroom wants to belong and be accepted by others. Relationships matter in the classroom, between students and between students and their teachers. Learners very quickly pick up whether their teacher cares about them as an individual. Glasser (1998) talks about the need to put emotional deposits into the relationship bank so that these can be drawn upon when needed. If a learner has gained respect and built a relationship with their teacher they are much more likely to develop the resilience to be able to cope with tough conversations and disciplinary measures.

Alliances and affiliations

There are many additional relationships within a education setting that support diverse learners. There are often well-established alliances and affiliations; support networks and varied collaborations. Classrooms are complex and challenging learning environments, and catering for the range of students is a challenging. yet rewarding part of teaching. Unfortunately, all too often the relationship between an education setting and its community can easily become unwelcoming and inaccessible (Groundwater-Smith, Ewing & Le Cornu, 2014).

It then becomes important that school community members form strong alliances to support learners. In schools, where professionals and families work in a strong alliance to support a student, an increased prevalence of inclusive practices is evident. For example, consider a year five teacher who has 25 students in the class, seven are refugee migrants classified as EALD [English as an Additional language or Dialect], and two have Down Syndrome. This teacher needs the support and advice of EALD specialists in the field and support from external advisory staff. Meaningful contributions by the parents/carers [with the support of an interpreter where needed], medical professionals, fellow staff and school leaders. A school wide approach is essential so that effective support is not only provided in the year 5 teacher’s classroom but also in the playground, and as these children move in and out of other classroom contexts.

Mutual emotional and technical support

Sometimes teachers are their own worst enemies. Too often, teachers operate behind closed doors with high levels of stress because of an overwhelming sense of inadequacy at the enormity of their task. Stress levels in teachers can be traced to professional isolation and increasing complex classroom environments associated with increased student diversity, expanding levels of intensity of students’ needs, and larger class sizes, all of which contribute to a progressively more challenging work environment (Sands, et al., 2000).

Teachers need to support each other, share their expertise and have frequent access to support personnel who have some expertise in particular fields. No one teacher can be expected to be an expert on the various needs of all the students in their classroom. An open sharing culture must be established where school basic norms and assumptions (Schein, 1992) include the belief that every child is every person’s responsibility and that there is no shame or blame attached to admitting difficulties in meeting student needs and asking for support and advice (Carter & Abawi, 2018).

Building professional teams is important and can work well even across-school contexts. Teachers need the support and advice from others in the field, experts, paraprofessionals, parents/carers. In schools there are a number of resident and visiting specialists (guidance officers, speech language therapists, psychologists, youth workers) who can support a classroom teacher. Sands et al., (2000) refer to the importance of ‘transdisciplinary teams’ that made up of a team of individuals who work together to support the needs of a student where expertise and ideas are shared in order to support a learner ‘s needs and build a sense of community, connectedness, belonging, affiliation and mutual support.

Characteristics of collaboration

For transdisciplinary teams to work effectively, there must be a spirit of collaboration. Collaborative individualism first conceptualised by Limerick and Cunnington (1993), is now becoming regular practice in many schools. When working collaboratively, members share responsibility, accountability and decision making, respect others’ opinions, and build trust and mutual support. Productive partnerships in schools enable inclusive school practices to thrive, and can be applied to partnerships in transdisciplinary teams and partnerships with families.

Characteristics of supportive and effective partnerships

• Opportunities are created for authentic dialogue and reflection.

• Trust of, and respect for each other is established.

• Each other’s knowledge is valued.

• Clear structures and focus are identified and used.

• Roles within the group within the group are identified and defined.

• Roles in observing and teaching are shared (Saggers, Macartney & Guerin, 2012).

Potential obstacles to effective partnerships

• Policies promoting partnership are not realized in practice.

• The school is a hostile environment where the physical and emotional environment and school practices become intimidating.

• Educators assume they alone know what is best for a child.

• The student is not respected, not included in decisions about their program and their input is not valued.

• Parents are directed as to what to do.

• Parents are treated as having a disability and seen as part of the problem rather than part of the solution(Saggers, Macartney & Guerin, 2012).

characteristics of inclusive classrooms

Ashman (2015) describes six enabling characteristics essential to the creation of inclusive classrooms.

1. Independent access

Learners are able to physically access facilities, venues and learning activities safely and independently.

2. Prerequisite skills required for a learning task

Learners are provided with opportunities to develop and perform the prerequisite functions and skills of the learning task.

3. Adequate social skill levels

Learners have appropriate social skills that enable them to participate effectively in the learning task.

4. The presence of social networks

Learners have the ability to develop personal friendships.

5. Valued membership

All learners are valued members of the education setting.

6. Active involvement

All learners are actively involved in the design and organisation of their own learning.

But how easy is this to achieve? Where do we start? We can begin with a change of mindset which is reflected in the language that is used within the classroom and across a school.

CHARACTERISTICS OF INCLUSIVE LANGUAGE

What is inclusive language?

Inclusive language is language that is free from words, phrases or tones that reflect prejudiced, stereotyped or discriminatory views of particular people or groups. It is also language that doesn’t deliberately or inadvertently exclude people from being seen as part of a group. Inclusive language is sometimes called non-discriminatory language. (Department of Education Tasmania, 2012, p. 2)

Because language is our main form of communication, using non-discriminatory language avoids false assumptions, stereotyping and exclusion and promotes respectful productive relationships. Indeed research has shown that there is a symbiotic relationship between language used within a education setting context and the characteristics of the education setting culture that exists (Abawi, 2013), so evidence of an inclusive education setting culture can be heard in classrooms, playgrounds, and staffrooms.

Throughout 2017 and 2018, a number of the authors of this textbook have been conducting a research project within 6 schools spread across one broad region of Queensland. As data has been analysed researchers have discussed the preliminary findings and concluded that in three of the six schools involved in the research, there is clear evidence that inclusive language and practice is embedded within every aspect of school life, whilst in the other schools although there is a willingness and a desire to be inclusive there is still work to be done. The extract below is taken from a transcript of the researchers’ conversation as they unpacked the recorded conversations with a range of school Principals, Deputy Principals, teachers, teacher aides, and Heads of Special Education Programs.

It’s that feeling of personal connection that comes through – at some of the other schools there just does not seem to be a true connection to the kids. It was more of an intellectual exercise with strategies rather than heart. There needs to be that moral imperative and a passion… Rhetoric and process cannot make up for passion to make a difference in a child’s/young person’s life… It’s the ‘how’ in the schools where inclusion is effective it’s not the fine grained ‘what’ but the how and the holistic view… It’s powerful the language that is used – they talk strategies broadly but then they talk about how they evidence that so that you can actually see that student has improved… Data use and the pedagogy of inclusion is differentiated for students and for teachers – they clearly acknowledge that. The way they talk about each other and the way they talk about staff is always positive – you don’t hear negativity… there is a shared language and meaning – so there is a repertoire of strategies being used and they know them.(L. Abawai, C. Andersen, C. Brownlow, S. Carter, R. Desmarchelier, T. Leach, J. Lawrence & M. Turner [personal communication, 2018]).

family partnerships in inclusive schools

In some schools, family involvement is sometimes limited to formalised parent/teacher interviews and attendance at key functions. In others, where there is an embedded culture of families as equal partners, families are respected as active decision makers about their child’s educational and co-curricular programs. They are also very involved with the strategic planning and direction of the school, actively participating in School Councils Boards, committees and taskforces.

The level of family involvement in education settings varies from family to family, teacher to parent and education setting to education setting. Yet as Bottrell and Goodwin (2011) noted, relationships between education settings, families and communities are recognised as important to children and young people’s wellbeing and learning, from early childhood through primary and secondary education. Although some parents have had negative experiences in their own lives of education, and do not always have the confidence or are sometimes less likely to want to be involved, it is important that educators and education settings reach out and try and remove these barriers. Establishing productive and positive partnerships with families is critical in creating inclusive classrooms and settings .

Recognising and respecting diversity in families

In building productive partnerships with families, it is important that teachers consider the following:

- Accept of the composition of the family.

- Respect for the ways in which families function and make decisions.

- Shift away from thinking that the educator is the sole ‘expert’.

- Be mindful of one’s own beliefs and values that are shaped by personal history, life experience and education and how these influences the decisions.

- Be cautious of judgements that can be made about students and their families.

- Have an awareness of the cultural, ethnic and linguistic heritage of students.

- Avoid generalising or stereotyping.

- Learn about the cultures represented in the education setting.

- Be aware of the communication styles or level of context that families use.

(Sands et al., 2000)

Watch

Working with parents and the issues facing families (17.00 minutes)

summary

Teachers can make a significant difference to the learning outcomes of students by:

- having high expectations as the norm;

- using a strength based approach to learning;

- using a rigorous curriculum that develops higher order thinking skills;

- using learning and assessment tailored for individual need;

- using sensitive ways to support students to not feel excluded (for whatever reason) from school events therefore ensure principle led decision-making regarding curricular and co-curricular activities;

- building quality relationships and partnerships with students and their families/carers built on trust, discretion, non-antagonist approaches to poor behaviour and disengagement;

- avoiding stereotyping or judgmental thinking regarding students and their families and/or carers;

- analysing materials for cultural bias;

- promoting literacy enjoyment and critical literacy skills; and

- forming broad support teams, interventions and programs.

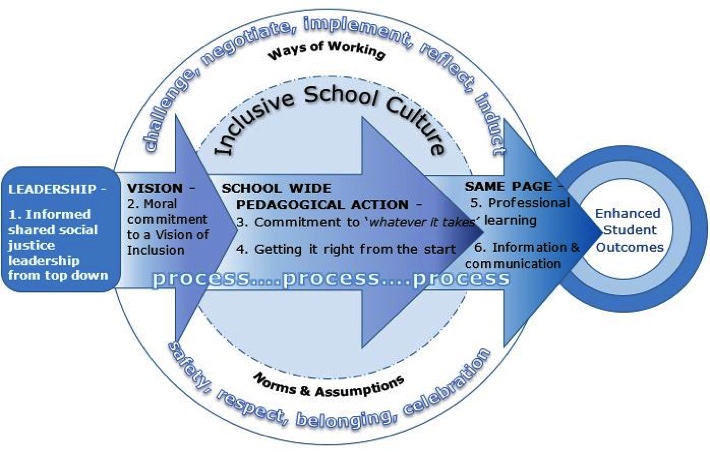

Schools can make a significant difference in the educational outcomes of students by creating an inclusive school culture through the alignment of inclusive practices. [School culture is conceptualised in terms of the seminal work of Schein (1992) regarding organisational culture.] In the Openaccess book entitled New Pedagogical Challenges in the 21st Century, in Chapter 3 Inclusive Schoolwide Pedagogical Principles: Cultural Indicators in Action, Abawi, Carter, Andrews and Conway (2018) highlight the following themes as being key indicators of an inclusive school.

- Organisation and structures that are strongly student centred and inclusive.

- Best fit choices are made for students, teachers, teacher aides, resources and environment.

- Explicit teaching of social skills and the valuing of diversity.

- Clear communication, shared language and shared expectations.

- Positive relationships building between staff, students, parents and community.

- A strong sense of safety, family and wrap around support.

- Transitions into and out of school are prioritised.

- Teachers use information and data to plan adjustments and engage learners.

- Differentiation and inclusive pedagogies are articulated negotiated and actioned.

- Professional learning and sharing occurs between staff members.

- Evidence of strong ethical and moral Principal leadership.

- Targeted informed leadership evident at all levels of the school.

These various factors are captured in Figure 3.13 below:

Consider your context – how inclusive is it? Is diversity truly celebrated and embraced for the richness it brings? If not what could you do to start the discussion?

references

Abawi, L. (2013). School meaning systems: the symbiotic nature of culture and ‘language-in-use’. Improving Schools, 16(2), 89-106.

Abawi, L. (2015). Inclusion from the gate in: wrapping students with personalised support. International Journal of Pedagogies and Learning, 10(1), 47-61.

Abawi, L., Andersen, C., Brownlow, C., Carter, S., Desmarchelier, R., Leach, T., Lawrence, J. & Turner, M., (2018). Personal Communication – unpacking research data and meaning. Previously unpublished.

Abawi, L., Carter, S., Andrews, D. & Conway, J. (2018). Inclusive schoolwide pedagogical principles: cultural indicators in action. In O. Bernad-Cavero & N. Llevot-Calvet’s (Eds.), New pedagogical challenges in the 21stCentury. Intechopen. Retrieved from https://www.intechopen.com/books/new-pedagogical-challenges-in-the-21st-century-contributions-of-research-in-education

Anderson, L., Krathwohl, D. A. & Bloom, B. S. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessment: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. London, England: Pearson Longman.

Ashman, A. (2015). Education for inclusion and diversity. Melbourne, Australia: Pearson.

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2018). 2016 Census findings. Retrieved from http://www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/D3310114.nsf/home/Home

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2015). Disability, ageing and carers, Australia: Summary of

findings, 2015. Retrieved from http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/mf/4430.0

Australian Council of Social Service (ACOSS). (2012) Poverty in Australia, 3rd edition. Retrieved November 16, 2015 from http://acoss.org.au/images/uploads/Poverty_Report_2013_FINAL.pdf.

Australian Government Australian Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. (2015). Closing the

Gap : Prime Minister’s Report. Retrieved from

http://www.dpmc.gov.au/sites/default/files/publications/Closing_the_Gap_2015_Report_0.pdf

Australian Government. (2008). Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority Act 2008: Act No. 136 of 2008. Retrieved from https://www.comlaw.gov.au/Details/C2014C00108

Bodkin-Andrews, G., & Carlson, B. (2016) The legacy of racism and Indigenous Australian identity within education, Race Ethnicity and Education, 19(4), 784-807. doi: 10.1080/13613324.2014.969224 .

Bottrell, D., & Goodwin, S. (2011). Schools, communities and social inclusion. South Yarra, Australia: Palgrave Macmillan.

Carter, S. & Abawi, L. (2018). Leadership, inclusion, and quality education for all. Australasian Journal of Special and Inclusive Education, 42(1), 49-64. doi: 10.1017/jsi.2018.5.

Cohen, S., Crawford, K., Giullari, S., Michailidou, M., Mouriki, A., Spyrou, S. & Walker, J. (2007). Family diversity: A guide for teachers (A project under the second transnational exchange programme). Retrieved from http://www.csca.org.cy/doc/Family Diversity Guide, English.pdf

Davis, K., Christodoulou, J. Seider, S. & Gardner, H. (2011). The theory of multiple intelligences. In R.J. Sternberg & S.B. Kaufman (Eds.), Cambridge Handbook of Intelligence(pp. 485-503). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Department of Education Tasmania (2012). Guidelines for inclusive language. Hobart, Australia: Tasmanian Department of Education. Retrieved from https://documentcentre.education.tas.gov.au/Documents/Guidelines-for-Inclusive-Language.pdf

Duncan, G.J. (1993). Economic Deprivation and Early-Childhood Development. Paper presented at the Biennial Meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development. New Orleans, United States of America.

Ferguson, H.B., Bovaird, S., & Mueller, M.P. (2007). The impact of poverty on educational outcomes for children. Journal of the Canadian Paediatric Society. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2528798/

Freiere, P. (1968). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York, NY: Seabury Press.

Gardner, H. (2006). Multiple intelligences: New horizons. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Gilbey, K., (2018). StaffEd [Presentation]. Springfield, Australia: University of Southern Queensland.

Glasser, W. (1998). Choice theory: A new psychology of personal freedom.New York, NY: Harper.

Gorski, P.C. (2012). Perceiving the problem of poverty and schooling: Deconstructing the class stereotypes that mis-shape education practice and policy. Equity and excellence in education, 45(2)302-319. doi: 45:2, 302-319.

Groundwater-Smith, S., Ewing, Le Cornu, R. (2014). Teaching challenges and dilemmas.Melbourne, Australia: Cengage Learning Australia.

Hyde, M. (2010). Diversity and inclusion in Australian schools. Melbourne, Australia: Oxford University Press.

Limmerick, D. & Cunningham, B. (1993). Managing the new organisation: A blueprint for networks and strategic alliances.Chatswood, Australia: Business and Professional Publishing.

Malala Yousafzai Quote (2013). Retrieved July 23, 2019, from Wiki quotes:

https://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/Malala_Yousafzai

Ministerial Council on Education, Employment, Training and Youth Affairs (MCEETYA)

(2008). Melbourne declaration on educational goals for young Australians. Retrieved from http://www.curriculum.edu.au/verve/_resources/National_Declaration_on_the_Educational_Goals_for_Young_Australians.pdf

Morris, A. & Burgess, C. (2018) The intellectual quality and inclusivity of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander content in the NSW Stage 5 History syllabus. Curriculum Perspectives, 38(2),107-116. Retrieved from https://www.erudit.org/en/journals/mje/2013-v48-n2-mje01045/1020974ar/abstract/

Nakata, M. (2006). Australian Indigenous studies: A question of discipline. Canberra, Australia: Aboriginal Studies Press.

Nakata, M. (2011). Pathways for indigenous education in the Australian curriculum framework. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 40, 1-8. doi:10.1375/ajie.40.1.

National Neurodiversity Symposium Syracuse (2011). What is Neurodiversity? Retrieved from

https://neurodiversitysymposium.wordpress.com/what-is-neurodiversity/

Parkinson, C., & Jones, T. (2019) Aboriginal people’s aspirations and the Australian Curriculum: a critical analysis. Educational Research for Policy and Practice 18,(1)75-97.

Payne, R. K. (1995). A framework : understanding and working with students and adults from poverty.

Baytown, TX: RFT Pub.

Peariso, J.F. (2008). Multiple intelligences or multiply misleading: The critic’s view of the multiple intelligences theory.Doctoral dissertation, Liberty University. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED500515.pdf

Peters, S. (2007). Inclusion as a strategy for achieving education for all. In L. Florian (Ed.), The SAGE handbook of special education,(pp. 118-132). London, England : SAGE Publications Ltd. doi:10.4135/9781848607989.n10.

Riley, T., & Pidgeon, M. (2018). Australian teachers voice their perceptions of the influence s of stereotypes , mindsets and school structures on teachers’ expectations of indigenous students. Teaching Education, 0:0, 1-22.

Rothman, S. (2003). The changing influence of socioeconomic status on student achievement: Recent evidence from Australia. Retrieved from: http://research.acer.edu.au/Isay-confernece/3

Royal College of Psychiatrists (2016). Useful resources. Retrieved from https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/

Queensland Department of Education. (2016). Engaging the community within Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander early education. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oLgT2qutf_A

Sachs, J. (2003).The activist teaching profession. Philadelphia, PA: Open University Press.

Saggers, B., Macartney, B., & Guerin, A. (2012). Developing relationships that support learning and participation. In S. Carrington & J. Macarthur (Eds.), Teaching in inclusive school communities. Melbourne, Australia: John Wiley & Sons.

Sands, D.J., Kozlwak, E.B. & French, NK. (2000. Inclusive education for the 21st century: A new introduction to special education. Colorado, CO: Wadsworth.

Saunders, P., & Wong, M. (2012). Promoting inclusion and combating deprivation: Recent changes in social disadvantage in Australia (research report).Retrieved from https://www.sprc.unsw.edu.au/media/SPRCFile/2012_12_FINAL_REPORT.pdf

Schein, E. H. (1992). Organisational Culture and Leadership (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Schleicher, A., (2017). Better education outcomes for Indigenous students. Teacher Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.teachermagazine.com.au/articles/better-education-outcomes-for-indigenous-students

Shaddock, A.J., Giorcelli, L. & Smith, S. (2007). Students with disabilities in mainstream classrooms: A resource for teachers. Canberra, Australia: Department of Education, Science and Training.

Slee, J., (2011). Addressing systemic neglect of young indigenous children’s rights to attend school in the Northern Territory, Australia. Child Abuse Review, 21(2),99-113. Retrieved from https://doi-org.ezproxy.usq.edu.au/10.1002/car.1166

TEDx Talks. (2015, Sep 1). The truth about growing up disabled [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tvNOzJ7x8qQ

TEDx Talks. (2016, Dec 20). Inclusive education: A way to think differently about difference [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FolCetXtYG0

TEDx Talks. (2017, Jul 6). Invisible diversity: A story of undiagnosed autism [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cF2dhWWUyQ4

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) (2009). Policy Guidelines on Inclusion in Education. Retrieved from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0017/001778/177849e.pdf