8 Opening eyes to vision impairment: Inclusion is just another way of seeing

Melissa Cain

How can teachers best support students who can’t access the curriculum and content through their vision?

Key Learnings

- Vision impairment can be classified as damage or disease to the eye or visual system and is considered a disability when it cannot be corrected with the use of glasses or medication.

- There are visual behaviours that may alert teachers to undiagnosed vision impairment.

- Students with vision impairment should have the same access to quality education as their peers, but may experience physical, social, emotional, and academic barriers to education.

- Positive teacher attitudes and perceptions about disabilities are important in creating an inclusive culture.

- There are many visual images and representations used in the curriculum, therefore, students with vision impairment require adaptions or alternative technologies to access information.

- Students with severe vision impairments or who are blind need an Expanded Core Curriculum to teach compensatory skills, including working with the latest digital technologies and developing social skills.

INTRODUCTION

For students with vision impairments, access and inclusion in education settings can be overlooked as facilities are generally set up for those who can see. Many elements that help to create an inclusive and safe learning environment such as the school culture, behaviour management, and curriculum are displayed in visual format. Think about your journey into a school, through the office, into the classroom and around the school grounds, and the incidental learning you acquire through visual means.

This chapter examines the educational, physical, and social impact of vision impairment and the development of a mindset supportive of designing curriculum opportunities to overcome barriers encountered by students with vision impairment. It investigates the implications of adjustments to curriculum, assessment, and pedagogy, as well as a student’s ability to move independently and confidently within and between classrooms and throughout the school. This chapter suggests ways for enhancing the social competence of students with vision impairment who may find it difficult to interact with their peers due to missing the sighted cues implicit in social norms which are most often shared through non-verbal communication (Wolffe, 2012). It also addresses ways to raise the awareness of those without vision impairment to the realities and complexities for those whose eyesight is impaired.

An important part of learning about the realities of teaching students with vision impairments is hearing the voices of those who appreciate the complexities, or have experienced vision impairment in their lives. In this chapter, we present three narratives which provide points of view or ‘lenses’ through which you can experience what schooling might be like for a student with a vision impairment. The student lens serves to demonstrate the importance of resilience, advocacy, and access. The parent lens highlights the importance of physical and social inclusion for students with vision impairment and the role of support services in assisting the family, and the educator lens highlights the necessity of modifications to ensure students have equitable access to the curriculum. You will be asked to make links between the theoretical content presented and these stories to gain a holistic understanding of the impacts of vision impairment in schools and to discover that inclusion is just a different way of seeing.

UNDERSTANDING VISION IMPAIRMENT

Vision is a sense that allows students to learn incidentally, synthesise information, and respond to the environment. Vision motivates movement by providing information and stimulation, integrates and organises information in the brain, and encourages social interaction (Gentle, Silveira, & Gallimore, 2016). In classrooms, barriers can exist for students with vision impairment as the curriculum, the way it is delivered, and common assessment methods in the mainstream classroom are designed for those who can see (Morris & Sharma, 2011).

Students with vision impairment may have difficulty understanding where objects are in the environment and may need to use a white cane to travel independently. In addition, students with vision impairment are often unable to collect information from visual cues. Being able to interact confidently and in culturally appropriate ways is important for social inclusion and a sense of belonging, however, the vast majority of communication occurs through non-verbal means such as body posture, arm and hand gestures, and facial expressions , all of which students with a vision impairment may not be aware.

Learning Objectives

It is anticipated that upon completion of the chapter you will have:

-

An understanding of vision impairment and how vision impairment impacts students socially, physically, emotionally and academically in education.

-

An understanding of the legal and ethical requirements for educators to demonstrate the core tenets of the inclusive education agenda, and the difference that can be made by creating a culture of inclusion.

-

A range of strategies to assist students with vision impairment or blindness including Universal Design and the Expanded Core Curriculum.

DEFINING VISION IMPAIRMENT

We define vision impairment as a limitation in the eye or visual system which results in vision loss.

One image shows a blurred image as seen by a person with a moderate near vision impairment. The faces are blurred, which means the person with vision impairment, would not be able to see any details such as eye colour, or facial expressions.

The International Classification of Diseases 11 (World Health Organisation [WHO], 2018) defines vision impairment as:

- Mild –visual acuity worse than 6/12

- Moderate –visual acuity worse than 6/18

- Severe –visual acuity worse than 6/60

- Blindness –visual acuity worse than 3/60

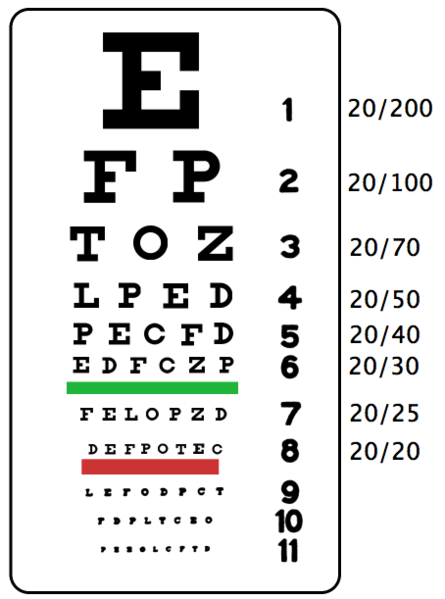

For school aged children, visual acuity is usually measured on a Snellen Vision Chart (Sue, 2007) (Figure 3). A person with perfect vision should be able to read the bottom line of the Snellan Vision Chart at six metres. This is recorded as 6/6 or 20/20 vision, which refers to the imperial measurement in feet. A child with a visual acuity of 6/12 has a mild vision loss, meaning they can see at six metres what a person with perfect vision could see at 12 metres. A severe vision impairment of 6/60 or more is considered legally blind (Vision Australia, 2018).

The image shows a Snellen Vision Chart which has the letters starting large at the top and small at the bottom.

Causes of vision impairment

Damage or disease to any part of eye or the structure can cause impaired vision. The visual system is very vulnerable (Deloitte, 2016) and if left untreated, abnormalities in vision can become permanent. Vision impairment is heterogeneous due to the complex nature of the visual system (Kelley, Gale & Blatch, 1998). The vast array of causes of vision impairment means that each child has their own particular educational needs and adjustments.

Childhood severe vision impairment or blindness can be caused by:

- Hereditary conditions such as genetic disorders;

- Intrauterine trauma such as Rubella or Foetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder [FASD];

- Perinatal conditions from prematurity or brain injury; and

- Acquired impairment due to untreated conditions and accidents, trauma, or cancers.

(Gilbert & Foster, 2011)

Incidence of Vision Impairment

Although some children with vision impairment may have other disabilities and attend special education units, the majority of students with vision impairment attend mainstream schools throughout all geographical areas of Australia (Media Access Australia, 2013). In Australia, it is estimated that there are 3,000 children with a vision impairment (Morris & Sharma, 2011). Indigenous Australians are three times more likely to have a vision impairment due to the high incidence of uncorrected or undiagnosed refractive errors (Foreman et.al., 2016), and children in low socio-economic areas are more likely to have vision impairments due to undiagnosed refractive errors, low take up or follow up of infant eye screening, intrauterine malformations, or decreased perinatal health (Deloitte, 2016). Due to the low incidence of severe vision impairment and blindness, it may be unlikely for you to come across a student with very low vision. In fact, less than 320 students in Australia have been identified as having a severe vision impairment or blindness (Deloitte, 2016).

Effect of Vision on Development

Vision is known as the co-ordinating sense which combines information gathered from all the senses to construct concepts about the environment. For sighted people, most learning opportunities are obtained incidentally from visual information (Ferrell, 2016). Vision provides incentive to the child to interact with their environment and engage with others.

A vision impairment impacts:

- Motor development (reaching, crawling, walking);

- Cognitive development (incidental learning of the world through sight);

- Social development (visual cues and facial expression, as well as social interactions).

Although babies with vision impairment develop through similar stages (Geld, 2014), they require direct, planned, and repetitive contextual experiences, providing auditory information to assist concept development (Ferrell, 2011). Early intervention is important to be able to access support and services and achieve full developmental potential (Lueck, Erin, Corn & Sacks, 2010).

Individual Characteristics

The cause and severity of vision impairment will be different and unique for every child. How a vision impairment impacts on a child’s development, will depend on:

- the degree and type of impairment;

- the age at the time of impairment;

- the presence of other developmental or learning needs;

- the child’s personality and abilities;

- fluctuations in time of day or eye fatigue;

- family environment and support; and

- access to early diagnosis intervention, support, and engagement.

(Royal Institute for Deaf and Blind Children [RIDBC], 2016).

Functional vision is the term given to how students use their vision and other sensory information to interact in the environment (Telec, Boyd & King, 1997) ). Functional vision can be increased by teaching students multiple ways to access information and through a positive mindset.

It has been well documented that certain personality traits, such as self-determination, creative and divergent thinking, being goal directed, and striving for accuracy create successful learners (Australian Council on Education Employment Training and Youth Affairs, 2008; Mindful by Design, 2013). In the article The Skills of Blindness: What Should Students Know and When Should They Know It, Wright (2007) argues that advocating for one’s own learning is also a useful tool for students and helps them develop skills for advocating for themselves in the workforce. Self-advocacy is reliant on the child’s personality and the classroom culture. Providing a safe and encouraging learning environment will encourage students with vision impairment to speak out when they cannot see information or when need additional assistance.

Bishop and Rhind’s (2011) research of students in tertiary education with vision impairment highlights that the success of a student is socially determined by the student’s self-identity. They also found that the attitudes of the child’s parents, as the first teachers, and their peers through acceptance and social interaction, assist students with vision impairment to develop a positive self-concept.

Watch this video of Kirsten to see how vision impairment affects her everyday life and how she has found ways to negotiate her environment, be successful in school, and advocate for her own wellbeing. Getting to know all your students, their learning preferences, and finding ways for them to participate and best demonstrate their understanding is key for good teaching practice (Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership [AITSL], 2018).

Watch

Kirsten’s Video ‘Disability and Development’ 10:04 min

Undiagnosed Vision Impairments

In Australia, developmental checks are performed at certain times throughout a child’s development and if there are any concerns, children are referred for specialist assistance (Deloitte, 2016). According to the Australian Register of Vision Impairment, (RIDBC, 2014) only 72% of vision impairments are diagnosed in the child’s first year. Therefore, it is possible that teachers may be the first one to notice the effects of vision loss and recommend that the child sees a specialist for an assessment.

Thurston (2014) notes there could be up to one in five students in early years classrooms with undiagnosed and correctable vision impairments. Refractive errors causing difficulty in reading and attaining satisfactory literacy levels have a major impact on academic achievement. Such vision problems could usually be addressed with corrective glasses and/or minor modifications in the classroom.

There have also been concerns that as access to digital technologies and screen time increases, so does the potential for vision problems (Rosenfield, 2016). Visual fatigue occurs when eye muscles tighten during visually intense tasks which causes the muscles to become uncomfortable, dry, and irritated (Sheppard & Wolffsohn, 2018). In the last four decades, the time spent on laptops, mobile phones, tablets, and other devices has increased rapidly, with children now spending more than two hours of screen time a day (Vision Council, 2016). Smaller, portable screens mean closer viewing distances, which increases the demand on the eye to accommodate the image (Sheppard & Wolffsohn, 2018). Studies have shown an increased risk of dry eye disease in children, affecting the long-term health of their eyes (Moon, Lee, & Moon, 2014). Ocular migraines have also been associated with digital screen time, due to glaring or flickering lights and/or strain on the eyes (Sheppard & Wolffsohn, 2018).

As a teacher there are certain behaviours or characteristics that might alert you to the fact that a student may have vision impairment. Telec, (2009) suggest these may include:

- appearance of eyes – turned, red, teary, or student blinks excessively;

- complaints – headaches, dizziness, blurry, watery eyes, or light sensitivity;

- behavioural – head turning across the page, head tilted to one side, holds books very close to the face, rubs eyes frequently, becomes irritated when completing written work;

- eye movement – loses place when reading, uses finger to track the words, omits small words, writes up or down on the paper;

- eye teaming abilities – seeing double, repeats letters, misaligns digits, squints, tilts head, postural deviations, eyes shake;

- eye-hand coordination – feels objects, poor hand–eye coordination; and

- refractive – difficulty copying from board to paper.

A timely diagnosis by medical experts and referral to intervention is essential to allow children with vision impairment access to services to support physical, academic and social requirements of school (Anthony, 2014; Janus, 2011). In some states in Australia such as Queensland, important support is provided for classroom teachers by specialist Advisory Visiting Teachers [AVTs] who visit the school and make recommendations for modifications in the classroom. The work of AVTs is to “support the access, participation, and achievement of students with a disability” (Queensland Government, 2018).

In the following video, Dr Michelle Turner interviews Melissa Fanshawe on how to recognise and support vision impairment in the classroom.

Watch

Inclusion and Diversity: Diagnosing Vision Impairment video 19:20 min

Reflection

- Have you met a person with a vision impairment?

- If so, what did you notice about the way they negotiated their environment and written information?

- How might you feel if one day you began losing your vision?

- What services in your local community might you access to assist you in teaching a student with vision impairment?

attitudes and teacher perceptions

the role of teacher perception AND ATTITUDES

Helen Keller said “not blindness, but the attitude of the seeing to the blind is the hardest burden to bear”. People have been known to speak louder to someone with vision impairment and change conversational words to avoid using ‘seeing’ or ‘looking’.

As vision impairment is a low incidence disability, many teachers may not have interacted with a person with severe vision impairment or blindness and feel underprepared and nervous about catering for their needs in the classroom (Brown, Packer, & Passmore, 2012). ‘Lack-of-knowledge’ theory purports that the lack of information about a topic or proposition confirms that the proposition is false. Hollins (1989) notes that lack-of-knowledge theory can be applied to issues of vision impairment, and asserts that many people have not had any prior experience with people who are blind and therefore don’t have prior knowledge to base their opinions. They therefore rely on their own assumptions, which results in a misalignment between expectations and solutions. This can also lead to a deficit view (seeing the disability as a hindrance and that students lack the ability to achieve) rather than focusing on the many abilities and strengths of the student. Making connections a person with a vision impairment or blindness is the most effective way to gain insight into, and a foundation of knowledge about the range of challenges, abilities, and successes.

Watch the video Don’t Dis my ABILITY which shows the daily activities of Graham Hinds, a person who is blind. In this video, Graham demonstrates how people with vision impairment are independent and capable and provides some tips on interacting with people who are blind. The video is ‘Audio Described’ so that it is accessible to people with low vision.

High Expectations: academically, socially, and behaviourally

It is well argued that students who have a vision impairment should be held to the same academic, social, and behavioural standards as students who are sighted (Rosenblum, 2006; Tuttle & Tuttle, 2004; Wolffe, 2012). Holbrook and Koenig (2000) believe that students who have a vision impairment need to be given the same accessible content to ensure that (i) students acquire what is needed in that subject, (ii) do not have diminished expectations from their peers, and (iii) are prepared for adulthood when they will be judged equally in competitive employment markets. Social skills are equally important as behavior influences the attitudes of others as the basis for employment, social participation, and community and reflects on their self-concept and self-esteem (DeCarlo, McGwin, Bixler, Wallander & Owsley, 2012; Wolffe, 1999).

Developing a Culture of Inclusion

Opportunity, participation, and a sense of belonging in the school setting are paramount to positive social and cognitive development for students with vision impairment (DeCarlo, et al., 2012). It is important to create learning environments that allow for independence and provide age appropriate activities in a manner that can be achieved successfully (Beardslee, Watson Avery, Ayoub, Watts & Lester, 2010). Olmstead (2005) believes that success for students with disabilities comes in part from the “schools’ commitment to inclusion” in practice (Olmstead, 2005 p. 65) Abawi, Fanshawe, Gilbey, Andersen and Rogers share more information in Chapter 3 of this text, Celebrating Diversity: Focusing on Inclusion.

Our legal responsibilities as teachers

Creating a culture of inclusive, safe, and supportive environments is not just best practice, it is an ethical and legal requirement for all educational contexts in Australia. Australia hasn’t always supported inclusive education in mainstream schools for students with a disability, and for many years exclusion or integration was the norm. The 1990s saw a strong push towards inclusive education for all students with several key policies and statements being instituted (Foreman & Arthur-Kelly, 2014). Perhaps most importantly, Australia became a signatory to the Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education in 1994 (The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization [UNESCO], 1994). Other documents that will guide your work as educators and with which you should become familiar include the Disability Discrimination Act (1992), the Disability Standards for Education (2005), the Melbourne Declaration on Educational Goals for Young Australians (2008), and the Professional Standards for Teachers (AITSL, 2012). The Disability Standards for Education (2005) mandate that we as educators “make reasonable adjustments to assist a student with disability to participate in learning, and to demonstrate knowledge and understanding” (Department of Education, Training and Employment, n.d., p. 1). Refer to chapter 3 for further information about teachers’ legal and ethical responsibilities regarding diversity and inclusion.

THE IMPACTS OF VISION IMPAIRMENT ON EDUCATION

Vision impairment can impact physical, social, emotional, and academic participation in education.

Physical impacts of vision impairment on education

Motor skills, development, speech and vestibular development can be delayed with congenital vision loss (Telec, Boyd, & King, 1997). Neck posture and gait may also be affected by students as they accommodate their body to visual field loss. For students with decreased vision in one eye, lack of depth perception creates greater perceptual uncertainty, affects hand-eye coordination and balance required for daily routines, sports, and hobbies (Ekberg, Rosander, von Hofsten, Olsson, Soska, & Adolph, 2013).

For students with vision impairment, moving through the school can be difficult due to reduced sight to navigate through spaces. The general layout of the school will impact mobility as gauging the depth of steps, positioning of playground equipment, and changes in gradient are difficult. As you heard in Kirsten’s story, the time of day, glare, and number of people around can impact on accessibility. Effective mobility skills and spatial awareness are important to confidently navigate the school environment.

Depending on their level of vision and their location within the classroom, students with vision impairments may find it difficult to see the whiteboard, or continuously copy from the board to their books. Glare from the windows may impact their viewing of books, computers, or the whiteboard. Trip hazards may exist with chairs and bags that are in pathways and can’t be seen.

In a study of students with vision impairments aged 10-12, Stuart and Lieberman (2006) found that physical activity of children with a vision impairment was significantly less than their fully sighted peers, and levels for physical activity decreased relative to the levels of vision. Physical education classes may be difficult to access due to equipment, programming and instruction, however, the many benefits of physical activity and social inclusion in sport, particularly team sports, means it is essential for teachers to find ways to overcome these barriers for full participation (Lieberman, Haegele, Columna & Conroy, 2014).

Watch this video about Goalball, a Paralympic team sport and the only one designed specifically for people with a vison impairment or blindness. Goalball is fast paced, requiring excellent aural attention and spatial awareness.

Watch

‘Goalball’ 01:13 min

Social impacts of vision impairment on education

Acceptance by peers is important to develop a sense of belonging and positive self-concept. Self-concept is developed by feelings of acceptance and a person’s perception of how others view them (Rosenblum, 2006). Students who are blind or have severe vision impairment often lack social competence which can affect their ability to bond with other students (Rosenblum, 2006). They may lack the ability to recognise faces or to initiate conversations, and may not gather intricate social cues such as facial expressions and body gestures (Fanshawe, 2015). Many students with low vision may have socially inappropriate behaviours, such as not respecting personal space, as they are unable to see correct behaviours modelled.

Emotional impacts of vision impairment on education

A student’s personality and a positive mindset to overcome challenges will also impact their ability to cope with vision impairment (Fanshawe, 2015). Research in several Western countries has revealed that students with vision impairments often feel lonely and isolated from their peers (George & Duquette, 2006). Students do not like to perceive themselves as different, particularly in the teenage years (Ihrig, 2013), and using white canes or reading Braille highlights such differences. Feelings of, and inadequacy and anxiety about their ability to cope with the academic workload have also been reported (Ihrig, 2013).

Whether the vision impairment was congenital or acquired will impact psychosocial adjustment (Tuttle & Tuttle, 2004; Welsh, 2010). An acquired loss of vision will be more difficult to adjust to, particularly if students have lost the ability to work or participate in sports and hobbies they once enjoyed (Ihrig, 2013).

Academic impacts of vision impairment

Vision impairments create a particular challenge in the Australian mainstream classroom, as the content and the assessment of the curriculum is designed for those who can see (Telec, 2009). Visual images are throughout classrooms and schools in the form of posters, signs, and displays. Multimedia is embedded throughout the national curriculum with many visual images and videos, models, and symbols for students to decode. Subjects such as Science, Mathematics, Geography, History, and Visual Art have proved infinitely more difficult to access by students with low vision (Rule et.al., 2011). These subjects contain a high number of graphical representations, diagrams, graphs, tables, and pictorial representation of data. Students with vision impairments studying these subjects cannot see important information and often rely on working memory to access this information (Rokem & Ahissar, 2009) which can result in increased cognitive load.

Reflection

Take time now to read the three lenses of vision impairment; a child, a parent, and a teacher

- Are there any common themes?

- How does seeing the different viewpoints help you to understand the impact of vision impairment?

- What physical, social, emotional, and academic impacts can you identify in these narratives?

- How might you respond if you were Oska’s teacher?

- How does reading the parent’s story help you to understand the emotional impact on the parent?

three lenses of perspective: child, parent and teacher

The following three narratives provide authentic perspectives on how vision impairment effects education. We hear firstly from Oska, a primary student about what he encounters on a day-to-day basis in his school. Next, we hear from a parent of another child with vision impairment and the effects on family, accessing services, and expectations for inclusive education for her son Mika. Finally, we hear from a teacher who without experience or training managed to successfully negotiate teaching a student with vison impairment, Katie, and the wealth of learning opportunities that presented.

Child’s lens: Oska’s story. Listen to the audio of Oska 05:03 min (Transcript – Appendix 1).

Parent’s lens: Mika’s story. Listen to the audio of Mika’s mother 08:21 min (Transcript – Appendix 2).

Teacher’s lens: Katie’s story. Listen to the audio of Katie’s teacher 04:43 min (Transcript – Appendix 3).

SUPPORTING INCLUSION OF STUDENTS WITH VISION IMPAIRMENT IN MAINSTREAM CLASSROOMS

Family, Culture and Community

Long before a student enters your classroom, their parents, carers, family and early intervention specialists have been developing the child’s skills to orientate themselves in space and move safely around their environment. It is important for you to be aware that having a child with a disability is a major emotional journey for parents (Davis & Day, 2010; Tanni, 2014). Prior knowledge, cultural, and religious beliefs towards disabilities will impact how a family provides support for their child (Chen, 2009, Waldron, 2006). It is important that educators are respectful of the decisions and choices parents have made in the child’s interests and work together to ensure maximum participation in the educational settings. If it is recommended that a student has an Individual Education Plan [IEP], this must be completed with the knowledge of the teacher and the approval of the parent or carer. In most States students with a vision impairment will have their disability verified attracting government funding. This will assist the teacher and school to apply the recommended adjustments in the IEP possible.

Universal Design: Considerations of vision in the learning environment for all students

As mentioned in Chapter 3, a culture of inclusion needs to be created throughout the school to ensure students have a sense of belonging (Abawi, Fanshawe, Gilbey, Andersen, & Rogers, 2018). This includes not just school staff and students but also the school community in a systemic manner. Inclusive culture aims to create a school environment that is designed for the universal needs of all the students within the school so that low vision does not impair a person’s participation. Adjustments, accommodations, and differentiation are all used interchangeably throughout this chapter to refer to any “measure or action taken to assist a student with disability to participate in education on the same basis as other students” (Australian Government Attorney General’s Department, 2005, p. 10). Universal design for learning means creating a learning environment which promotes access to the curriculum, learning and teaching for all learners.

Access to information

Writing

- Ensure contrast, font, size, clutter, and line spacing is legible.

- Minimise unnecessary copying of tasks.

- Use 2B pencils or black marker pens for recording.

- Use large font on the board or interactive whiteboard.

- Place posters and other visual prompts around room within visual fields.

Technology

- Allow activities and testing to be completed on a computer.

- Promote inbuilt accessibility options or preferred settings to enlarge font.

- Train students in ‘shortcuts’ for quick access to system commands.

- Develop keyboarding skills and touch typing to allow for typed responses.

Textbooks

• The Marrakesh Treaty set in June 2013 (World Intellectual Property Organisation 2013), allows a relaxation on copyright laws for people with a print disability, which allows all materials from textbooks to be provided by the publisher in electronic format, allowing them to be enlarged.

Digital media

• Ensure font is large, use a contrasting colour and avoid clutter.

Auditory skills

- Provide different ways for students to accurately express their knowledge.

- Provide timely and constructive feedback in a students preferred style: written, typed, auditory.

Visual fatigue

- The 20-20-20 rule is suggested to maintain eye health; after 20 minutes of screen time, you should look for 20 seconds at something 20 feet away (6 metres) (Rosenfield, 2016).

- Provide ways to reduce cognitive load and assign realistic workloads and homework tasks.

Organisation

- Plan ahead to have materials prepared or emailed for accessibility.

- Teach students how to organise materials within their ‘tidy tray’ for quick access.

- Teach students how to use files on the computer to store information.

Environment

School Culture

- Ensure achievable expectations of academic curriculum.

- Foster a safe, supportive and inclusive environment and promote independence.

- Encourage students to advocate for the ways they learn best.;

- Support students to develop social inclusion through positive friendships and a sense of belonging.

School grounds

- Highlight any hazards in the environment such as steps by using yellow strips.

- Cover drains and other trip hazards.

Classroom Organisation

- Organise the classroom to allow sufficient space for ease of access.

- Consider lighting that is bright enough but does not produce glare.

- Plan the layout of desks to ensure all students have good access to the board.

Pedagogy

- Use explicit verbal instructions so students are aware of what is happening and when.

- Verbalise writing as you put it on the board.

- Ensure examples are modelled and scaffolded.

- Equitable learning experiences for all students.

Modifications for Severe Vision Impairment

Holbrook and Koenig (2000) believe students should have a variety of tools that they can use to access the curriculum as independently as possible. Students with severe vision impairment can use a combination of auditory and tactile technologies to assist them accessing the curriculum such as screen readers, touch typing, Braille, and auditory recordings. This toolbox of different technologies allows students to participate in the classroom through the independence to choose which tool will assist them to access the curriculum and engage in the learning environment.

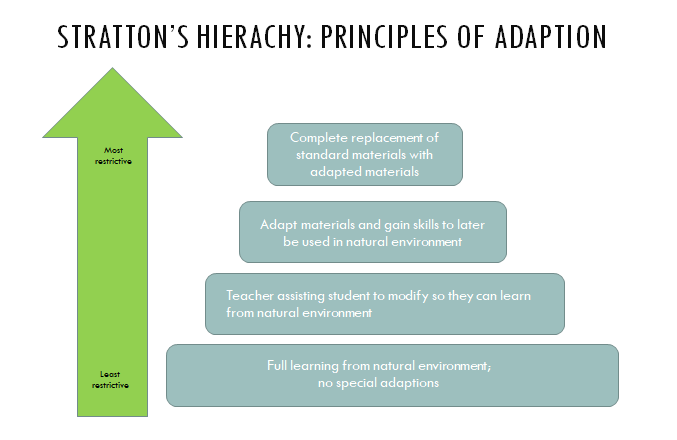

Stratton’s (1990) Principles of Adaption, proposes a hierarchy to assist educators when making adjustments to the core curriculum. The model recognises the importance of modifying the curriculum based on the student’s individual set of needs. It proposes the use of the least restrictive methods at all times, so the students can connect and interact with their environment as much as possible (Stratton, 1990). Stratton proposes four levels of adjustments in his model (Figure 8.5).

The least restrictive method (bottom layer of Figure 8.5) is when the theory of Universal Design for Learning (Rose, 2000) is used, in which, curriculum design provides multiple means of representation, expression, and engagement to suit the needs of all learners. The second level, is the teacher providing modifications so the student can learn in the classroom. This may be in terms of larger print, enlarged diagrams, or printed Braille. The third level requires some modifications to be made to curriculum and assessment to meet academic demands. This may be necessary when the materials contain complex visual images, such as cartoons, videos, learning objects, diagrams, and maps. If this still does not allow access to the learning activity at the same level as their peers, educators need to look at entirely different ways to ensure the student is able to participate in the learning.

Expanded Core Curriculum

Inclusion in the classroom is facilitated by allowing students to independently access the academic and social curriculum in the classroom. To fully participate in education The South Pacific Educators of Students with Vision Impairment (2004), believe that students need to be exposed to an Expanded Core Curriculum (ECC). The ECC comprises of nine areas that require explicit teaching to students with vision impairment to compensate for skills sighted peers gain incidentally by observing others.

Assistive Technology

Assistive technology includes specific tools that enable students to access information. It can include Braille machines, screen reading software, mobile phones, iPads, and magnifiers.

Career Education

Career education provides students with vision impairment an opportunity to be exposed to the jobs that they may not be aware of without the ability to observe people working. It includes understanding the student’s strengths to make decisions about suitable careers.

Compensatory Skills

Compensatory skills are the skills necessary for accessing the core curriculum. This can include study skills, access to enlarged print, tactile graphics, and Braille.

Independent Living Skills

Independent living skills include the tasks required in everyday life, hygiene, dressing, cooking, eating, and chores to increase independence.

Orientation and Mobility

Orientation and mobility (O & M) instruction helps students to become aware of where their body is in space and how to travel safely. It may include cane training, travelling in the school of community, and using public transport.

Recreation and Leisure

Recreation and leisure is important for belonging and participation. Assistance in becoming aware of many physical and leisure activities allows social interaction and is good for well-being.

Self-Determination

Self-determination includes making decisions, solving problems, and advocating for oneself. Students who know about themselves as learners and advocate for what they need will be able to be more successful.

Sensory Efficiency

Sensory efficiency incudes using other senses and systems (proprioceptive, kinaesthetic, and vestibular systems) to be able to access and participate in their environments.

Social Interaction Skills

Social interaction skills explicitly teach social skills and promote awareness about facial expressions, body language, and interpersonal relationships that cannot be learned by visually observing people.

conclusion

Vision is the sense that provides information about the environment and as such, students with severe vision impairment may miss incidental information and important social cues. Vision impairment is a low incidence disability that can impact physical, social, emotional, and academic engagement within a school if modifications are not made to promote inclusion.

Academic and social inclusion in schools is important to model the diversity of the community. Being inclusive of students with disabilities in the classroom, helps all students develop empathy and understanding for their peers (Rosenblum, 2006). It is important to note that designing learning activities for all students does not mean designing for the average student. In fact, studies demonstrate that when you design for the average, the outcomes usually suits no-one (Rose, 2016). Classrooms can be designed to suit the individual needs of all students which will encourage active participation for students with vision impairment. Students should be provided a toolbox of technologies both digital and traditional, which can help then access the curriculum. The Expanded Core Curriculum is therefore important for students with severe vision impairment and blindness to access knowledge and skills that will help compensate for their vision loss. It is likely that you will have children with mild or moderate vision impairments in your classroom. It is also possible that you may identify issues with students’ vision within your classroom. Armed with the knowledge from this chapter, it is hoped that you can modify content in the least restrictive manner and use pedagogies that create an inclusive culture and promote active participation of all students in the classroom.

Meaning Making

- How would access to information be different for student with vision impairment?

- Why is it important to promote social inclusion in the classroom?

- What behaviors could be evident if a child could not access information easily or effectively?

Reflection

- How can you provide information home to parents that may have vision impairments?

- How can parents/ grandparents with vision impairment be included in parent/teacher/student school activities?

- What else can cause problems for an individual with vision impairment in a school? (e.g. people walking around on iPhone not looking).

- How can teachers manage their own visual fatigue?

references

Abawi, L., Andersen, C., Famshaw, M, Gilbey, K. & Rogers., C. (2018). Chapter 3 :Celebrating Diversity: Focusing on Inclusion. Toowoomba, Australia: University of Southern Queensland Open Access Text.

Allman, C.B., Lewis, S., & Spungin, S.J. (Eds.). (2014). ECC essentials: Teaching the expanded core curriculum to students with visual impairments. New York, N.Y: AFB Press.

American Academy of Ophthalmology (2002).Computers, devices and eye strain. Retrieved from https://www.aao.org/eye-health/tips-prevention/computer-usage

Anthony, T. (2014). Family support and early intervention services for the youngest children with visual impairments. Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness, 108(6), 514-519.

Australian Council on Education Employment Training and Youth Affairs. (2008). Melbourne Declaration on Educational Goals for Young Australians. Retrieved from www.mceetya.edu.au

Australian Government Attorney General’s Department. (1992). Disability Discrimination Act 1992.Retrieved from http://www.comlaw.gov.au/Details/C2010C00023.

Australian Government Attorney General’s Department. (2005). Disability Standards for Education. Retrieved from http://www.ag.gov.au/www/agd/agd.nsf/Page/Humanrightsandanti-discrimination_DisabilityStandardsforEducation

Australian Government Department of Education and Training. (2016). Disability Standards for Education 2005. Retrieved from https://www.education.gov.au/disability-standards-education.

Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership [AITSL]. (2012). The Australian Professional Standards for Teachers. Retrieved from https://www.aitsl.edu.au/

Australian Paralympic Team. (2013, Aug 25). Goalball [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rUYL0TUNEcM&feature=youtu.be

Beardslee, W., Watson Avery, M., Ayoub, C., Watts., Lester, P. (2010). Building resilience: The power to cope with adversity. Retrieved from https://vawnet.org/material/building-resilience-power-cope-adversity

Bishop, D., & Rhind, D. J. A. (2011). Barriers and enablers for visually impaired students at a UK Higher Education Institution. British Journal of Visual Impairment, 29(3), 177 -195.

Brown, C. M., Packer, T. L., & Passmore, A. (2013). Adequacy of the regular early education classroom environment for students with visual impairment. The Journal of Special Education, 46(4), 223-232. doi:10.1177/0022466910397374.

Chen, D. (2004). Considerations for working with families of differing cultural and linguistic backgrounds. In D. Gold & A. Tait (Eds.), A strong beginning: a sourcebook for health and education professionals working with young children who are visually impaired or blind (pp. 187-207). Toronto, ON: Canadian National Institute for the Blind.

Corn, A.L., & Erin, J.N. (Eds.). (2010). Foundations of low vision: Clinical and functional perspectives (2nd ed.). New York, NY: AFB Press, American Foundation for the Blind.

Davis, H., & Day, C. (2010). Working in partnership: the family partnership model. London, England: Pearson Education.

DeCarlo, D., McGwin, G.,Bixler. M., Wallander, J., Owsley, C. (2012). Impact of paediatric vision impairment on daily life: Results of focus groups. Optometry and vision science: official publication of the American Academy of Optometry, 89 (9), 1409 – 1416.

Deloitte (2016).Socioeconomic impact of low vision and blindness from paediatric eye disease in Australia. Retrieved from https://www2.deloitte.com/au/en/pages/economics/articles/socioeconomic-impact-low-vision-blindness-paediatric-eye-disease-australia.html

dontdismyability. (2015, Nov 16). Don’t Dis my ABILITY: Day in the life (Audio description included)[Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KE0eG9qphlE

Ekberg, T., Rosander, K., von Hofsten, C., Olsson, U., Soska, K., & Adolph, K. (2013). Dynamic reaching in infants during binocular and monocular viewing. Experimental brain research 229. Retrieved from https://psych.nyu.edu/adolph/publications/Ekberg%20Rosander%20von%20Hofsten%20Olsson%20Soska%20Adoph%202013%20Dynamic%20reaching%20in%20infants%20during%20binocular.pdf

Fanshawe, M., (2015). The implications of monocular vision on orientation and mobility. Journal of the South Pacific Educators in Vision Impairment 8(1), 77-86.

Ferrell, K. (2011). Reach out and teach: Helping your child who is visually impaired to learn and grow.New York, NY: AFB Press.

Foreman, J., Keel, S., Xie, J van Wijngaarden, P., Cowston, H., Taylor, H., & Dirani, M., (2016). National eye health survey 2016. Retrieved from http://www.vision2020australia.org.au/uploads/resource/250/National-Eye-Health-Survey_Summary-Report_FINAL.pdf

Foreman, P., & Arthur-Kelly, M. (Eds.). (2014). Inclusion in action (4th ed.). South Melbourne, Australia: Cengage Learning.

Geld, R. (2014). Investigating meaning construal in the language of the blind: a cognitive linguistic perspective. Istraživanje konstruiranja značenja u jeziku slijepih: kognitivnolingvistička perspektiva, 40(77), 27-59.

Gentle, F., Silveira, S., & Gallimore, D. (2016). Vision impairment, educational principles and practice: Some Fundamentals. Sydney, Australia: RIDBC.

George, A., & Duquette, C., (2006). The Psychosocial experience of a student with low vision. Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness, 199(3),152-163.

Gilbert, C., Foster, A. (2001) Childhood blindness in the context of VISION 2020 – the right to sight. Bulletin of the World Health Organization (79)3, 227-32.

Holbrook, M. C., & Koenig, A. (2000). Basic techniques for modifying instruction. In M. C. Holbrook & A. Koenig (Eds.), Instructional strategies for teaching children and youths with vision impairment2, 173 – 193. New York NY: AFB Press.

Hollins, M., (1989). Understanding blindness. Hillsdale. NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Association.

Ihrig, C. (2013). Clinical pearls. Optometry & Vision Science, 90(3), 302-303.

Janus, M. (2011). Impact of impairment on children with special needs at school entry: Comparison of school readiness outcomes in Canada, Australia and Mexico. Exceptionality Education International, 21(2), 29-44.

Katie’s story [Audio recording]. (2018). Toowoomba, Australia, University of Southern Queensland.

Keeffe, J. (2005). Psychosocial impact of vision impairment. International Congress Series, 1282,167-173. doi: 10.1016/j.ics.2005.06.005.

Kelley, P., Gale, G., & Blatch, P., (1998). Theoretical Framework. In P. Kelley and G. Gale (Eds.), Towards excellence: Effective education for students with vision impairments (pp. 33-40). Sydney, Australia: North Rocks Press.

Lueck, A. H., Erin, J. N., Corn, A. L., & Sacks, S. Z. (2011). Facilitating visual efficiency and access to learning in student with low vision.Paper presented at the Division on Visual Impairments, Arlington, VA.

Lieberman, L., Haegele, J., Columna, L. and Conroy, P. (2014). How students with visual impairments can learn components of the expanded core curriculum through physical education. Journal of Visual Impairment and Blindness, 108(3), 239-251.

Lieberman, L., Houston-Wilson., Kozub, F., (2002). Perceived barriers to including students with visual impairments. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 19(3) 364–377.

Media Access Australia. (2013). Vision Education Scoping Report. Retrieved from: www.mediaaccess.org.au

Mika’s story [Audio recording]. (2018). Toowoomba, Australia, University of Southern Queensland.

Mindful by Design. (2013). Habits of the Mind. Retrieved from: http://www.habitsofmind.org/

Ministerial Council on Education, Employment, Training and Youth Affairs. (2008). Melbourne declaration on educational goals for young Australians.Retrieved from: http://www.mceetya.edu.au/verve/_resources/National_Declaration_on_the_Educational_Goals_for_Young_Australians.pdf.

Moon, J., Lee, M., & Moon, N. (2014). Association between video display terminal use and dry eye disease in school children. Journal of paediatric ophthalmology and strabismus , 51(2), 87-92.

Morris, C and Sharma, U (2011). Facilitating the Inclusion of Children with Vision Impairment: Perspectives of Itinerant Support Teachers. Australasian Journal of Special Education, 35, 191-203.

Olmstead, J. (2005). Itinerant teaching: Tricks of the trade for teachers of students with visual impairments(2nd ed.). New York, NY: AFB Press.

Oska’s story [Audio recording]. (2018). Toowoomba, Australia, University of Southern Queensland.

Queensland Government (2018). Advisory Visiting Teachers. Retrieved from: https://education.qld.gov.au/students/students-with-disability/specialist-staff/advisory-visiting-teachers

Royal Institute for Deaf and Blind Children [RIDBC] Renwick Centre for Research and Professional Development (2016). Australian Childhood Vision Impairment Register. Retrieved from https://www.ridbc.org.au/renwick/australian-childhood-vision-impairment-register-acvir

Rokem, A. & Ahisssar, M., (2009). Interactions of cognitive and auditory abilities in congenitally blind individuals. Neuropsychologia, 47(3), 843-848.

Rose., D. (2000). Universal design for learning. Journal of Special Education Technology, 15(3), 45-49.

Rose, T. (2016). The myth of the average students. NEA Today, 35(1), 13.

Rosenblum, L. P. (2006). Developing friendships and positive social relationships. In S. Z. Sacks & K. E. Wolffe (Eds.), Teaching social skills to students with visual impairments: From theory to practice (pp. 163-194). New York, NY: AFB Press.

RosenfieldM., (2016). Computer vision syndrome (A.K.A. digital eye strain). Optometry in Practice 17, 1-10.

Royal Institute for Deaf and Blind Children [RIDBC]. (2014) The Australian Childhood Vision Impairment Register newsletter for March 2014. Retrieved from: https://www.ridbc.org.au/renwick/acvir-newsletters

Rule, A.; Stefanich, G.; Boody, R. Peiffer, B. (2011). Impact of adaptive materials on teachers and their students with visual impairments in Secondary science and mathematics classes. International Journal of Science Education, 33(6), 865-887.

Sheppard, A., Wolffsohn, J. (2018). Digital eye strain: prevalence, measurement and amelioration. British Medical Journal Open Ophthalmology, 3(1).

Southcott, J. & Opie, J., (2016). Establishing equity and quality: The experience of schooling from the perspective of a student with a vision impairment. International Journal of Whole Schooling 12(2), 19-35.

Steer, M., Gale, G., & Gentle, F. (2007). A taxonomy of assessment accommodations for students with vision impairments in Australian schools. The British Journal of Visual Impairment, 25(2), 169-177.

South Pacific Educators in Vision Impairment. [SPEVI]. (2004). Principles and standards for the education of children and youth with vision impairments, including those with multiple disabilities. Retrieved from http://spevi.net/spevi/resources.php.

Steer, M., Gale, G., & Gentle, F. (2007). A taxonomy of assessment accommodations for students with vision impairments in Australian schools. The British Journal of Visual Impairment, 25(2), 169-177.

StrathearnSchool. (2012, Mar 14). Kirsten’s video ‘disability and development’ [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GAy0oKHbeYA

Stratton, J. (1990). The principle of least restrictive materials. Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness, 84, 3-5.

Stuart, M., Lieberman, L., & Hand, K., (2006). Beliefs about physical activity among children who are visually impaired and their parents. Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness, 100(4), 1-22.

Sue, S. (2007). Test distance vision using a Snellen chart. Community Eye Health, 20(63), 52.

Tanni, L. A. (2014). Family support and early intervention services for the youngest children with visual impairments. Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness, 108(6), 514-519.

Telec, F., Boyd, A. & King, J. (1997). Vision impairment: A reference manual. Sydney, Australia: NSW Department of School Education, Special Education Directorate.

Teplin, S. W., Greeley, J., & Anthony, T. L. (2009). Blindness and visual impairment. In W. B. Carey, A. C. Crocker, W. L. Coleman, E. R. Elias & H. M. Feldman (Eds.), Developmental-Behavioral Pediatrics (Fourth Edition)(pp. 698-716). Philadelphia, PA: W.B. Saunders.

Thurston, A., (2014) The Potential Impact of Undiagnosed Vision Impairment on Reading Development in the Early Years of School, International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 61(2), 152-164. doi:10.1080/1034912X.2014.905060.

Tuttle, D.W., & Tuttle, N. R. (2004). Self-esteem and adjusting with blindness: The process of responding to life’s demands (3rd ed.). Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas Publisher Ltd.

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization [UNESCO] (1994). Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action on Special Needs Education. Retrieved from http://www.unesco.org/education/pdf/SALAMA_E.PDF

Vision Council, the (2016). Eyes overexposed: The digital device dilemma: digital eye strain report. https://www.thevisioncouncil.org/content/digital-eye-strain.

Waldron, K.A. (2006) Teaching students with vision impairments in the multicultural classroom. Journal of the South Pacific Educators in Vision Impairment, 3(1), 29-34.

Welsh, R. (2010). Psychosocial dimensions of orientation and mobility. Foundation of Orientation and Mobility. New York, NY: AFB Press.

Wolffe, K.E. (Ed.)(1999). Conveying High Expectations. Skills for Success: a career education handbook for children and adolescents with visual impairments. New York, NY: American Printing House For The Blind.

Wolffe, K.E. (2012) Critical Social Skills[Powerpoint]. University of Newcastle, RENWICK. Retrieved from. https://uonline.newcastle.edu.au/bbcswebdav/pid-2207767-dt-content-rid-5878056_1/xid-5878056_1

World Health Organisation [WHO], (2013) Universal eye health: A global action plan 2014-2019. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/blindness/AP2014_19_English.pdf?ua=1

World Health Organisation [WHO], (2018).Blindness and vision impairment [Factsheet]/ Retrieved from http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/blindness-and-visual-impairment

World Intellectual Property Organisation (2013). Marrakesh treaty to facilitate access to published works for person who are blind, visually impaired, or otherwise print disabled. Retrieved from: http://www.wipo.int/treaties/en/ip/marrakesh/summary_marrakesh.html

Wright, L. (2007). The Skills of Blindness: What should students know and when should they know it? Future Reflections, 26(3), 26-34.

Appendix 1: child Perspective (transcript of audio)

My name is Oska, and I love sport, playing with my friends and lasagne. I also have a vision impairment. This is what my day looks like. When I wake up, I can’t see out the window to know if it is day or night. I ask Siri for the time. If it is time to wake up, I make my way to the bathroom. It’s three metres from my room to the bathroom door. I go to wash my hands, but my brothers always move the soap, so I have to find it first. The cupboard door was left open in the hall and I collide with it on my way to the kitchen to get my breakfast. It doesn’t hurt as I run into things all the time. My breakfast consists of cereal and milk. I know the containers even though I can’t read what is on the label. Once my mum bought juice in the same container as milk and I accidently poured it on my cereal, until I realised it didn’t smell like milk.After breakfast, my job is to unpack the dishwasher. Apparently, I sometimes leave things in there, even though I do my best. Everyone has to remember to pack sharp knives in the same place so I don’t cut myself.

I have a shower, I squirt out a bit of the container. It is thick and moisturising, so I know that it the conditioner. I get the other bottle and wash my hair. To get dressed, my school shirt is in a certain place in my drawers and has a different texture. They have tags on them to make sure they are the right way around. My socks are already paired for me and my shoes are in the cupboard. I pack my lunch, computer and my focus 40 Braille machine into my school bag. I play the trumpet, but even if you know Braille music, you have to remember the notes off by heart, so it makes it harder to play. I am band captain and I help set up for band. When I get to school, I walk with my brother up to class. I can hear all my friends say ‘hi’. I know them all by their voice. My friends and I go the classroom to line up.

It takes me a while to get my focus 40 paired with the computer. I’m really good at technology, but some days it won’t pair, which means I need to type everything and listen to screen readers. When this happens, it is frustrating as Braille helps me spell and punctuate and means I can easily go back and forth within a document. I seem to take longer than others to do my tasks, but my teacher gives me extra time, or if there isn’t he tells me which part to do. Last week at school I had to do two assessments. I’m pretty sure I got an A. Using Braille or listening to the words, is just a different way of getting the information. It’s the only way I know, so it is no problem for me. I can’t see the posters on the wall, but my teacher reads them all out to me at the beginning of the year and emailed them to me, so I have a copy if I need to.

The bell rings, I get my lunchbox and follow everyone down the stairs. Usually my lunch is in containers. One day mum gave me a sandwich in glad wrap and it took me half the break to open the thing. My friends offered to help but I ended up ripping the gladwrap. At playtime, we all run together to the oval to play tiggy. One of my friends run with me and tells me which direction to run, and the location of the person who is ‘it’. I can hear other people running around me and love the feeling of the air on my face. The bell goes and it is time to go back in. I move around the school easily as I have mapped where everything is. Usually all my friends are with me anyway. If my teacher is writing on the whiteboard, he reads it out as he writes it. If we need to copy it, he will send add it to my One Note, so I can access it electronically. Maths, Science, or HASS can be difficult if there is a graph or diagram. However, I have a PIAF machine, which raises the lines on a diagram by putting it through a laminator type machine. That was I can feel it in the same way as my friends see their diagrams.

When it is time to go home, I meet my younger brother outside our classroom. Sometimes he runs off and I have to call out or ask someone if they have seen my brother. After school I usually have homework, I do it quickly because I really love to ride my bike. My brother and I ride all afternoon. My brother rides in front of me, so I know where is safe to go. I still run into things a lot, but my bike and I are tough, and our backyard has been made quite safe for me. I probably should go on a tandem, but it is way more fun on my own bike. At dinner time, I can usually smell what we are eating. I get my knife and fork and just cut and put it in my mouth and hope for good flavours. Mum reads us a story. I lay with my eyes closed an imagine myself in the story. Sometimes after I go to bed and everyone thinks I’m asleep, I stay up late and read a Braille book. I usually dream about cars and about how I will get a good job, so that I can buy a fancy car and a driver, or maybe by then I will have a driverless car.

Appendix 2 : Parent Perspective (transcript of audio)

By the time my son Mika was born we had been living overseas for many years. After an emergency caesarean Mika was given a positive Apgar result and all seemed well. His sisters’ births were fairly routine with minor complications, and as Mika’s pre-natal scans showed nothing untoward, we assumed it was third time lucky. My son didn’t open his eyes until just before we were due to leave the hospital. It was only momentary glance but enough for me to notice the white cloudiness covering both eyes. I thought I should mention this to the nurse but didn’t feel particularly concerned. The next hour was quite confusing as a specialist was brought into investigate. “He can’t see” was the specialist’s delicate summary. “Are you sure, are you sure?” I questioned, still somewhat in a blur from the medication. “You don’t believe me? Then get another opinion!” That was the last we saw of the specialist and the start of our journey.

The first six months of Mika’s life was spent researching a very rare condition–-bilateral Peters Anomaly—and finding out that if there was to be any chance of sight, Mika would need a transplant or alternative operation as soon as possible; a narrow window of opportunity to activate the visual system to prevent amblyopia or permanent blindness. The country we were living in had no donated corneal tissue appropriate for a baby, and Australia did not send tissue to this country, so we were placed on the waiting list for a cornea from the US. Over time it became apparent that it would be a long wait to be at the top of the donation list, so we opted for an older and rarely used surgical alternative back in Australia. Four operations later and Mika had some peripheral vision at the top of one eye. A miracle it seemed.

And soon it was time for Mika to start pre-school. I wasn’t sure what to expect or whether he would be allowed into a ‘regular’ school. The country we were living in did not fully include students with a disability into mainstream schools and when I had left Australia in 1991, Australia had not subscribed to the inclusive education agenda, with the Salamanca Statement on Special Needs Education only signed in 1994. As an educator, I rarely had the opportunity to teach students with a disability. An international school said they would admit Mika with the only preparation being that we would ‘just see how we go’. The school had very limited experience with children with a disability and had not taught a student with vision impairment previously. Teachers, teacher assistants, and Mika figured it out as they went along. Mika had many, many falls as he could not see steps, changes in levels, and much of the playground equipment, so it seemed like he was at the nurse’s office every day. But despite his bruises, Mika was particularly resilient and determined to learn and play alongside his peers.

We moved back to Australia when Mika was in kindergarten and in year one he attended the local primary school his sisters had attended. Once again, the school had limited experience working with students with a disability, but from day one our experience was mostly very positive. I was very nervous about Mika learning the layout of the school as it was much bigger than his kindergarten and, as expected, Mika had daily trips to the nurse after running into poles or falling down stairs. After we learnt about the verification process, Mika’s disability was substantiated which meant that support agencies could be contacted, and some government funding would be received for additional help. An orientation and mobility expert from Vision Australia helped Mika to navigate the school. They made suggestions for adjustments such as reducing glare, the purchasing of a tablet on which words could be enlarged, and the use of contrasting colours in the classroom and on the playground (in particular, yellow-on-black). Vision Australia have been an amazing resource and Mika wouldn’t have had the success he had a primary school without their input. It wasn’t until the end of year five that Mika learnt to use a white cane which further increased his confidence. A distinct advantage was that the school has a Student Services Coordinator well versed in the legal requirements for teachers to adhere to the principles of inclusive education, as well as having extensive knowledge of practical adjustments.

Without exception Mika’s classroom teachers were accepting of the advice and assistance provided and embraced the suggestions for differentiation. There did not appear to be any limitations on his inclusion in everyday activities except for those suggested by his ophthalmologist, such as a ban on contact sports. Over the years Mika has taken part in dance, drama, softball, fencing, handball, choir and band. He attended school camps in years 4-6 including the year 6 adventure to Sydney and Canberra. Mika very much benefited from having an additional parent accompany him on this trip; someone to describe things he could not see, as well as the use of an Ipad to photograph and expand images at Australia’s Parliament House. Of course it has not always been smooth sailing for Mika, but these are points for learning. With an additional diagnosis of Rieger Syndrome and an action tremor, Mika has always struggled with fine motor skills and his hand writing is still almost illegible. Whilst he has had many sessions with an occupational therapist and was provided a scribe for activities that required lengthy written work, adjustments did not flow into other specialist subject areas such as visual art and Asian languages that use characters. Few alternatives were forthcoming in these areas. Whilst Mika had played the trombone for several years following the footsteps of his sisters, he struggled with seeing the music even when enlarged as much as possible. A significant dip in his eyesight at the end of year five coincided with a significant dip in his confidence in several areas. Although the purchase of a music reading app and wireless pedal looked promising, Mika became depressed at the thought of not succeeding in music and eventually gave up playing. Mika is to start learning Braille soon, but in hindsight it may have been best to begin this a lot earlier, so he could move to Braille music when the printed music became impossible to read.

I am reflecting on Mika’s journey whilst on holiday and Mika sets off for the beach again. Yesterday he learnt to snorkel and kayak for the first time, loving every minute. He is confident (fearless), resilient, and positive and is very much looking forward to starting high school next year. I have many reservations of course, especially Mika negotiating a new and much bigger school landscape and in time, public transport. Knowing that early visual loss can have profound effects on a child’s motor, social, emotional, and psychological development, Mika could be a very different child today had his journey not included open-minded, supportive, and caring teachers and specialists who believed he should have the same educational opportunities as his peers. His friends share the same qualities and are a fabulous support. Being surrounded by strong role models such as his fellow Goalball and blind golf players who have competed at international and Paralympic competitions gives Mika even more to strive towards. Inclusive education is not always this way, but it can be, and should be.

Appendix 3 : Teacher Perspective (transcript of audio)

I first met Katie in a rural school in Central Queensland. Having just entered Year 4 she was happy, well-spoken, and had been blind from birth.

As a relatively new teacher, I will be honest; I did panic the week before school started, when I found out Katie was going to be in my class. I had never met anyone who was blind and had no experience at all with working with people with no vision, and the thought of learning Braille was overwhelming! Katie was transferring from a different school so I was not able to meet with her previous teachers to hear about how they adapted the curriculum. Fortunately, our district had an Advisory Visiting Teacher (AVT) for vision impairment, who met with me and went through her case notes, to help me get a sense of who Katie was as a learner. With assistance, I worked out ways I would need to adapt the way I presented information, my teaching pedagogy as well as how I set up my classroom and group interactions.

When I first met Katie I was impressed with her persistence, resilience, and friendly nature. She quickly became a popular member of our classroom. I found Braille really intriguing, the coding element was really exciting and so did many other students. I did an online course, but to be honest Katie’s devices all translated into print on the computer, and she had support from the AVT for Braille, so the students and I learnt basic Braille and would use it to send messages of confirmation to each other throughout the week. We also used it for spelling activities, which became the favourite part of our week (and my students had the best spelling scores in the district). I had to be organised and know what I was teaching each week, so that it was available in Braille. A number of other students responded really well to my change of teaching pedagogy, which involved speaking as I wrote on the board, explaining everything verbally and describing illustrations in books, maps and diagrams in science. Brailling took longer than reading or writing, so although I did ensure Katie had work of the same academic integrity, I gave her only one or two examples (as long as she got them correct). Of course, there were occasions when something changed, or altered at the last minute and Kayla would become frustrated. I taught Katie to advocate for herself and tell me if something was inaccessible and we soon became good at thinking on our feet, having a student read something out, or I read everything to the class. However, through our preparations, on most occasions Katie was able to independently access what everyone was doing.

My classroom was the best laid out it had been in years. I had set up wide spaces between desks and put required items in accessible areas. Of course Katie bumped into chairs left out by the students every now and then, but I found that it gave the students a reason to tidy up after themselves, tuck their chairs in and walk slowly through the classroom. Katie was involved in lunchtime activities with her friends, who ate with her and then showed her where everything was in the playground. She particularly loved the monkey bars and could get there even without her cane, as she appeared to have mapped out the school.

When I started the year, I admit I felt sorry for Katie. I wondered how she would interact with others and how she would complete her work. By the end of the year, I was nothing short of inspired. With a few modifications Katie was doing what all her peers were doing, just accessing the content in a different way. I was impressed with her perseverance and resilient disposition. I also noted wonderful qualities of empathy and awe from the other students. Working together to help everyone, including Katie, to achieve goals was their priority and I am sure that having Katie in their class, meant they were more equipped to work with diversity and tolerance in their futures.

Teaching Katie had a profound impact on me. I decided to retrain as a teacher of the vision impaired and have since met many children who are blind. Just like the rest of our children, they are diverse in personality, ability, and confidence. Adaptive technology has improved greatly, with inbuilt screen readers on computers and iPads, electronic Braille devices, 3D printers and many general technology tools, such as the iPhone, that makes information so accessible.

Teaching is a career that makes a difference. Teaching a child with a vision impairment just requires rethinking your curriculum and pedagogy and a desire to see all children access education to reach their potential. I encourage anyone who has the honour of teaching a child with a vision impairment to use it as an opportunity to improve your own teaching and the minds of all the students in your class.