2 Different childhoods: Transgressing boundaries through thinking differently

Charlotte Brownlow

What does it mean to be different? How does difference influence the way we see ourselves and others?

Key Learnings

- View differences in ways that affords opportunities.

- Create environments that are supportive rather than challenging.

- Promote appropriate partnerships to enable successful learning and development.

introduction

These are important and complex questions to answer. Difference is evident in many settings and across the whole of the lifespan. At each developmental stage, individuals engage with systems, people, and broader environments, which allow varying degrees of agency on the part of the individual, from pre-school, school, higher education, and work.

A history of identifying difference

The identification of individuals as in some way ‘different’, ‘deficient’, or ‘other’ is not a new phenomenon, and disciplines such as psychology have had a significant influence on the definition and identification of individuals who do not necessarily fit within the dominant developmental path. This section will explore some of the ways that understandings of what is considered to be ‘normal’, and what behaviours transgress this, have become shared understandings, and the impacts that these ideas may have for the shaping of positive individual identities.

The discipline of psychology has had a strong influence in defining boundaries of normality, and such ideas have been readily taken up in other disciplines such as education. Philosopher Nikolas Rose (1989a) has argued that disciplines such as psychology, individualise children, which enables abilities to be measured and quantified with children being placed in categories based on calibrated aptitudes. Any variability in individuals can therefore be identified and appropriately managed. This consequently places a high importance on the need to fit in with the identified norms and the power to identify and intervene is firmly placed with professionals, namely psychologists and psychiatrists. Rose (1989a) argues that with the advent of psychometrics and the focus on the individual, psychology could develop its position as the appropriate authority to govern the lives of the individual. This rise of psychology to a powerful position led to a normalising vision of childhood and development. Rose (1989a) argues that the newly developed scales were not just a means of assessing children’s abilities, they provided new ways of thinking about childhood with the development of milestones of achievement. Such milestones led to ideas about appropriate childhood activities and ‘normal development’ that regulated the behaviours and understanding of a variety of groups, including parents and health workers. Burman (2008) proposes that this new position adopted by psychology was so powerful in its impact on the everyday lives of people that its ideals became taken for granted expectations about children’s development. This had broad reaching implications concerning the role of parents and families in fostering the development of the ‘normal’ child.

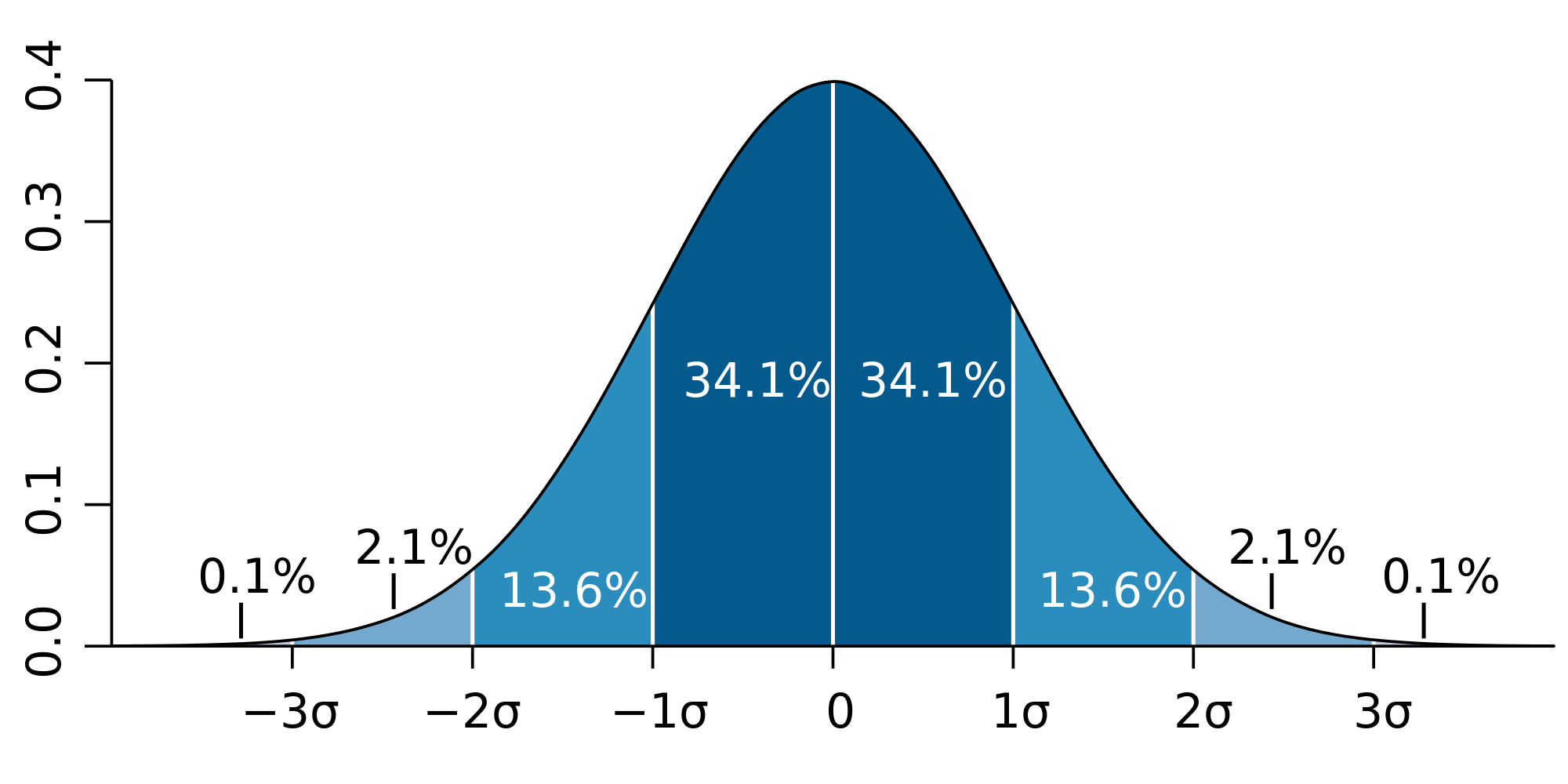

With the goal of measuring and regulating behaviour while monitoring any deviations from prescribed norms, came the important marrying of the concepts of human variability and the statistical principle of the normal distribution. By employing the concept of normal distribution, human variability could be presented in a simple visual form, with the assumption that human attributes varied in a predictable manner. Such patterns of behaviour therefore became governed by the statistical laws of large numbers (Rose, 1989a). Intelligence for example could now be quantified and intellectual abilities could now be presented as a single dimension, with an individual’s aptitude plotted within the distribution (Burman, 2008; Rapley, 2004; Richards, 1996; Rose, 1989b). This then enabled the appropriate action to be taken by the expert psychologist. Intellect and its variations had therefore become manageable and the transformation of ability into a numerical form could be used in political and administrative debates (Rose, 1990) such as tests for selective schooling. Rose (1989a) further argues that such concepts of normality are not gleaned solely from our experiences with ‘normal’ children but are also developed by experts drawing on the study of ‘abnormality’ or cases deviating from the prescribed norms in a given situation. The relationship between normality and abnormality is therefore symbiotic: it is the normalisation of individual development that enables the ‘abnormal’ developmental patterns to become visible, and vice versa (Burman, 2008). Rose (1989a) concludes that normality is therefore not an observation of a group of individuals, but a valuation.

This move towards the quantification of normality and transgressions from this, led to some individuals being labelled as ‘other’ – as ‘abnormal’, ‘lacking’, and ‘impaired’. Due to the statistical laws of the normal distribution, the majority of individuals would fit within the average scores, while a proportion of individuals are assumed to fit at the extreme scores – either above or below the average. Such graded understandings therefore lead to negative constructions of those individuals who fall outside of the tolerance of the boundaries of ‘normal’ behaviour. Once identified and labelled, the opportunities for negative self and ‘other’ identity abound. Such negative connotations of labels have an implicit (and often explicit) narrative concerning the assumptions of ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ behaviour, which impacts on individual interactions with others, who frequently consider us to be different or deficient based on acquired labels and observed differences.

One important challenge to this has been in the rise of self-advocacy movements, and while initially led by those with physical disabilities (Barnes & Mercer, 1996), these are now evident across other groups, such as autistic communities (Bertilsdotter Rosqvist, Brownlow, & O’Dell, 2015). These groups vary in action from political agitation to positive group identity on social media platforms such as Facebook, challenging members to question previously held assumptions by themselves and others. The call for action by such groups has been reflected in values such as ‘nothing about us without us’, challenging broader issues such as interventions and research.

This chapter will primarily focus on individuals who are different within the education system, particularly those who identify, or who are labelled by others, as being neurodiverse. The next section will therefore focus on the neurodiversity movement and some of the ways that this is challenging beliefs and action on diverse individuals.

A narrative of neurodiversity

The neurodiversity movement has been influential in challenging dominant ways of thinking about people who are in some way ‘different’. The term ‘neurodiversity’ was first coined by Australian researcher and activist Judy Singer in the late 1990s and has had widespread adoption within the autism community. The term however is not limited to autism and has been drawn on when considering difference across a range of labels including dyslexia, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder [ADHD], and attention deficit disorder [ADD] (Armstrong, 2010). One of the core principles of the neurodiversity movement is the shift in positioning of neurodiverse individuals from those who have a deficit to those who are different. The narrative is therefore one that draws on an abilities framework rather than a disabling framework. While it has had several critiques concerning its reduction of individuals to their basic neurology rather than their social position (see for example Ortega, 2013), proponents of the framework of neurodiversity argue that what it enables is a shift in thinking from positioning an individual as ‘impaired’ or ‘deficient’ to one where difficulties are acknowledged but are constructed as alternative rather than lacking.

Reflection

Think about a child or student that you have taught who is autistic.

- How might they be described in ‘education language’ and how might they be described reflecting on the principles of neurodiversity?

Such re-framings of understandings have important implications for identity, where individuals have more opportunities to craft a positive identity due to the alternative constructions of their label in the broader community. This has had an impact on the ways that labels are used and by whom. Traditionally a person-first language has been adopted, which refers to a ‘person with autism’ or a ‘person with dyslexia’. However, self-advocacy movements have consistently called for an identity-first use of language, which acknowledges that a label is an intricate and positive part of an individual’s identity rather than an ‘add on’, and therefore references such as ‘autistic person’ or ‘dyslexic’ are common. Scholars such as Harmon (2004) argue that identity-first language is crucial in the crafting of positive identities, as it highlights the central role that labels such as autism play within an individual identity. Harmon provides the example that it would appear strange to refer to someone as ‘a person with femaleness’ rather than ‘female’, and labels such as autism and dyslexia could be considered similarly. However, while an increase in the influence of the principles of neurodiversity has been seen, there is still no concrete agreement as to the terminology and individual preferences should always be respected.

In addition to the proposal of framing autism within a language of neurodiversity, individuals who do not attract a label have also been reframed in the narrative of neurodiversity. The terms ‘neurotypical’, ‘neurologically typical’, or the abbreviation ‘NT’ have been traced back to a self-advocacy organisation called Autism Network International (Dekker, 2000). Dekker notes that in order to avoid having to use the word ‘normal’ to refer to those without autism, a new term of NT was coined. NT is now commonplace within the autism community and is widely recognised by parents and some professionals, particularly in Europe and the United Kingdom. Additionally, terms such as ‘predominant neurotype’ [PNT], and allistic are also being increasingly used as alternatives to neurotypical, reflecting the ongoing development and shifting of language.

A shift in thinking in line with that of a perspective of neurodiversity calls into question issues of educational and social inclusion and the need to create equitable environments for individuals with a variety of learning needs. In the current Australian educational context, autism, or Autism Spectrum Disorder [ASD] as it is now referred to, following restructuring of the DSM-5, remains a supported learning difference within the classroom, but other types of neurodiversity, such as dyslexia, are rightly or wrongly no longer officially recognised. The following section will examine the challenges of inclusion across the educational spectrum.

Inclusion across the educational spectrum

Challenges for neurodiverse students within education in Australia are consistently documented in both academic research and government statistics, across all levels of the education spectrum (Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS], 2017; Cai & Richdale, 2015; Parsons, 2015). The figures reported by the ABS for autism within education highlight that 96.7% of children with an autism diagnosis have had some form of educational restriction, with additional support being required for most within educational settings. Of individuals aged 5-20 years attending an educational institution, 83.7% reported the experience of some form of difficulty within their educational context, spanning challenges with social encounters, learning difficulties, and communication difficulties (ABS, 2017). However, formal support was accessed by just over half of this population (55.8%), with 20.7% not receiving any additional assistance (ABS, 2017). Unsurprisingly therefore the ABS also reports that this population are less likely to complete an educational qualification beyond school, and people with other disabilities were 2.3 times more likely to have a bachelor degree than neurodiverse individuals (ABS, 2017). The flow on effects for employment are obviously apparent, with a labour force participation rate of 40.8% for neurodiverse workers, compared with 53.4% for individuals with disability and 83.2% of individuals without disability (ABS, 2017). Unemployment rates are just as alarming, with unemployment for autistic workers three times the rate for people with a disability, and almost six times that of people without disability (ABS, 2017). Of those who are in employment, challenges are frequently reported from a lack of workplace accommodations by employers, the difficulties of managing social encounters with co-workers, and stigma concerning their diagnostic label – all issues that do not impact on an individual’s ability to perform a job well (Brownlow & Werth, 2018). Additionally, individuals will need to navigate systems that are not immediately connected with the workplace on a regular basis. The National Autistic Society in the UK have documented some of these challenges in the following film: Diverted – NAS

There are also neurodiverse labels that are not recognised within the Australian education system, yet still require supports within schools. One of these is dyslexia. Dyslexia is recognised in Australia under the Disability Discrimination Act 1992 and by the Human Right Commission, yet New South Wales is the only state or territory where it is legally recognised as a learning disability. This is in stark contrast to countries such as Canada and the UK, which explicitly recognise and support dyslexia, with routine screening and support for learning within schools and support for training teachers.

The definition provided by the Australian Dyslexia Association to characterise dyslexia is as follows:

Dyslexia is a specific learning difference that is neurobiological in origin. It is characterised by challenges with accurate and/or fluent single word decoding and word recognition. Difficulties with spelling may also be evident. These challenges typically result from a deficit in the phonological and/or orthographic component of language. These challenges are often unexpected in relation to other strengths, talents and abilities. The ADA do not relate dyslexia to IQ since reading and IQ are not correlated. Dyslexia can remain a challenge throughout life despite mastery of language and literacy concepts; even with the provision of effective evidence-based classroom instruction. Secondary issues may include challenges in reading comprehension and reduced reading experience and these can impede growth of vocabulary and background knowledge. Dyslexia, if left unidentified and or unassisted, can cause social and emotional troubles. (Australian Dyslexia Association [ADA], 2018).

However, understanding what it might actually feel like to be dyslexic is often difficult. In recent times technological simulations of challenges have been created following the descriptions of dyslexic individuals. Try this Online Dyslexia Simulation.

As you can see, things that most of us take for granted such as letters remaining stable and in one place are not necessarily the case for some dyslexic people. As well as navigating the appearance of words and letters, the English language is littered with homophones and ‘exception to the rules’ spelling conventions – all of which need to be navigated by the dyslexic child.

The (un)predictability of English…

The duck swam in the pool while I had to duck to the shop.

The flour was milled to make a beautiful flower cupcake.

Their shoes are just over there.

Given the challenges to negotiate and the need to separate dyslexia from reflections on intelligence, developing a positive identity as a dyslexic can be challenging, despite many famous individuals who also identify as dyslexic being very vocal, such as Sir Richard Branson and actor Tom Cruise. The animation below describes what one dyslexic child would like his teachers to know about what it means to be dyslexic. Click here to view.

However, as with autism, and other neurological diversities, dyslexia is not something to be grown out of, and the challenges evident in childhood remain into adulthood. In the video below, Dan explains how dyslexia continues to impact on all aspects of his life. Watch Dan on Dyslexia.

As we can see from the video, dyslexia continues to have both an educational and social impact beyond school and the importance of fostering positive self-identities are therefore crucial.

Unlike dyslexia, autism has had much more of a focus within Australian educational contexts. However, the understandings of the experiential aspects of the challenges faced by autistic individuals are still not well understood. In 2016 the National Autistic Society in the UK launched their Too Much Information campaign, releasing a series of films depicting the sense of being overwhelmed that individuals may face across a range of situations. The first film featured 11 year old Alex and his experiences of being in a shopping centre:

Reflection

Think about a child that you have taught or know who is autistic, or an individual that you have worked with.

- How might they be experiencing some of the routines that are a part of everyday practice?

- What might be some of the major challenges throughout a typical day for them?

Nothing in isolation: the importance of intersectionality

So far, we have considered aspects of single points of difference, such as being autistic or dyslexic. However, we need to also consider issues of intersectionality and the impact of multiple influences on an individual. Two such influences are gender and socio-economic status, and an individual will always be influenced by factors such as these within their broader social context.

gender diversity

Increasingly, researchers and practitioners have moved away from binary understandings of gender, which categorise individuals as either ‘girl’ or ‘boy’, ‘man’ or ‘woman’, and instead have revised understandings to consider the complexities that influence an individual’s identification with a particular gender – or neither gender. In recent work Johnson (2018) explored the dominant understandings of gender evident in psychological theories and how a stable identification of oneself as either a girl or a boy has become evident of a key ‘normal’ developmental marker for individuals. Johnson critiques normative expectations for gender, particularly in childhood, and calls for a more critical reflection on what gender diverse childhoods might look like.

One area that has received increased attention within the research literature is that of the links between gender and autism. Traditionally research focusing on gender and autism has prioritised the higher prevalence of autism rates diagnosed in boys rather than girls, giving rise to the assumption of autism being traditionally considered a male condition (Taylor et al., 2016). However, in more recent years the under representation of females has been highlighted, with some researchers arguing that females may exhibit characteristics in different ways (Dworzynski et al., 2012). Lai et al. (2015) further propose that females may indeed present in more socially acceptable ways, and are therefore sometimes overlooked by clinicians for a diagnosis. This is often something anecdotally reported by educators, who typically describe the different behaviours of boys and girls with autism within classrooms, leading to boys more quickly attracting a label and therefore supports and interventions.

Reflection

Think about children in your classroom or other individuals who you believe to be autistic.

- Have any been ‘labelled’ as autistic, and if so did they identify as being male or female (or neither)?

- In what ways did they behave similarly or differently from each other?

While the research is providing some much needed reflection on the important impact that gender may have for an individual, this largely overlooks the intersectional nature of difference, and more attention needs to be given to the impacts on an individual of having two marginalised identities and how a person might negotiate these. What might it mean for an individual to be both autistic and gender diverse? Read the article from The Atlantic for an interesting perspective.

There are many children whose gender development does not align with traditional theories of gender development, and the term transgender is a broad term used to describe people who do not retain the gender identity that they were assigned at birth. Barker (2017) notes that these may mean quite different things for different people, with some identifying with the opposite sex, others may take steps to align their bodies with their identity, while some may retain a more fluid sense of gender identity. Cisgender is a term used to refer to people who retain their gender identity that they were given at birth. Though most people who the term cisgender describes would not label themselves, recognising this label may go some way to help de-marginalise people who do not conform to traditional gender identities (Barker, 2017).

Recent work by Kourti and MacLeod (2018) explored the experience of gender identity in a group of individuals who were raised as girls and identified as autistic but who did not necessarily identify with a specific gender. Kourti and MacLeod found that their participants did not identify with what could be considered ‘typical female presentations’, and resisted many gender-based social expectations and stereotypes. They therefore call for more complex understandings to be engaged in with respect to gender identity and autism, and focus on the importance of the intersectional influences on an individual of two or more powerful identity components.

It is therefore important to recognise that all of us will have more than one influence on our identity, and sometimes these may compete, while at other times they may be more complementary. Children therefore present with many influences, some of which are individual to them, and others which are shared socio-contextual issues.We need to be mindful of the complexities that can be associated with these intertwining challenges. While gender may be an example of an individual identity element, shaped by powerful social discourse, socio-economic status is something that we very much share with others, rather than ‘own’ as an individual.

The importance of socio-economic status

Socio-economic status is something that defines all of us, and reflects a spectrum of financial and social opportunities, and social positioning by self and others. For children in Australia who are neurodiverse, low socio-economic status may mean a delay in accessing professionals to effectively advocate for assessment and diagnosis due to the financial prevention of seeking this independently of supported healthcare systems. In 2016, the Autism CRC produced a report on diagnostic practices surrounding autism within Australia and found that there were stark differences between the public and private healthcare sectors in terms of the employment of multidisciplinary assessments and the frequency of diagnosis (Diagnostic Practices in Australia, CRC, 2016). The report found that while there was no cost associated with diagnosis within the public sector, there were long wait times. In contrast, a diagnosis could be more readily realised within the private sector, but with an average associated cost of $2750. The intersections therefore between socio-economic status and diagnosis and supports received by individuals is inextricably bound, and frequently not well understood.

In addition to financial barriers such as those associated with diagnosis, Woolhouse (2018) also highlights the social stigma that is associated with socio-economic status, and the likelihood of ‘mother-blaming’ or ‘culture blaming’ for those deemed to be in the ‘lower end’ of social brackets. Woolhouse (2018) proposes that children who are positioned outside of the ‘ideal’ white, middle-class family norm are frequently stigmatised. Woolhouse’s (2018) work focuses on eating practices and highlights that working class mothers are particularly scrutinised for their failure to prevent childhood obesity for example, through making ‘bad choices’ and are therefore considered ‘high-risk’. Scrutiny of mothers is not limited to eating practices, and mothers of neurodiverse children are frequently the focus of research (e.g. Benson, 2018), with the invisible outward presentation of autism often allowing an element of social judgement of the mother from on-lookers (Neely-Barnes, Hall, Roberts, & Graff, 2011). Social judgement is therefore frequently synonymous with perceived social class, and therefore the complex nexus between social status and diagnostic label can add a dual marginalised facet to an individual’s identity.

Within the Australian context a further consideration is where a child lives. Access to services and support are scarce and more difficult to access for children and families who live in rural settings.

Reflection

Individuals will have many things contributing to the crafting of their identity. We have focused on gender and socio-economic status.

- Can you think of other things that might impact on an individual and their positive sense of self?

Thinking differently within educational spaces: Three key learnings

In this chapter we have introduced some alternative ways of thinking about differences, ones that focus on an abilities framework. However, what does this mean for us as individuals and particularly for educators? We propose three key learning points from the points raised in this chapter.

Moving beyond impairments to view differences

One crucial aspect in starting to think differently is the need to reconsider how we view differences and the potential that such differences might provide. For example, can we use an abilities approach to understand a neurodiverse individual’s exceptional focus on particular interests to develop understandings of other areas? Is it possible to acknowledge difficulty, such as that of an individual with dyslexia, but find ways to support their different learning styles to create a sense of positive identity and self esteem?

Reflecting on our environments

Can we create more inclusive and accommodating environments for individuals to learn in? We saw earlier, through the eyes of Alex, how unpredictable and scary situations can be. Can we put ourselves in the place of someone who thinks differently so as to try and understand what some of the challenges might be? By understanding what individual’s find difficult, can we understand their behaviours more accurately?

The importance of partnerships

Experts are found in a range of roles, and we need to think broadly about what expertise a particular individual is bringing to a situation. Parents can bring experiential expertise in terms of knowledge about their children, and neurodiverse adults can provide a wealth of expertise in reflecting back on their experiences as children – these are not challenges but opportunities for shared learning.

Being an educator is a challenging profession – one that requires a negotiation of many different roles and contexts. Creating an environment that is inclusive in respecting the different needs of all individuals is a key focus, and marginalising those who think differently creates a missed opportunity for both the individual and society more widely. Not fitting into a set educational context and the management of this in a positive way requires thinking differently for all, requiring us to open our eyes to a range of complex diversities.

references

Armstrong, T. (2010). Neurodiversity. Discovering the extraordinary gifts of autism, ADHD, dyslexia, and other brain differences. Philadelphia, PA: Da Capo Press.

University of Southern Queensland [USQ](Producer). (2015). Arthur’s story [Animation].

Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS]. (2017). Autism in Australia. Retrieved from: http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Lookup/4430.0Main%20Features752015

Australian Human Rights Commission. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.humanrights.gov.au

Autism CRC. (2019). Retrieved from https://www.autismcrc.com.au

Barker, M-J. (2017). Gender, sexual, and relationship diversity [GSRD]. Good practice across the counselling professions 001. Lutterworth, England: British Association for Counselling and Psychotherapy.

Barnes, C. & Mercer, G. (1996). Exploring the divide: Illness and disability. Leeds, England: The Disability Press.

BBC Sesh. (2018, Sep 26). I won’t let dyslexia beat me [Facebook post]. Retrieved from https://www.facebook.com/bbcsesh/videos/2213681085563190/

Benson, P. R. (2018). The impact of child and family stressors on the self-rated health of mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder: Associations with depressed mood over a 12-year period. Autism, 22(4), 489-501.

Bertilsdotter Rosqvist, H., Brownlow, C., & O’Dell, L. (2015). “An association for all” – notions of the meaning of autistic self-advocacy politics within a parent-dominated autistic movement. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 25, 219-231.

Brownlow, C. & Werth, S. (2018). Autism Spectrum Disorder: Emotion work in the workplace. In S. Werth and C. Brownlow (eds.), Work and Identity: Contemporary Perspectives on Workplace Diversity. Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan.

Burman, E. (2008). Deconstructing developmental psychology (2nd ed.). London, England: Routledge.

Cai, R. Y., & Richdale, A. L. (2015). Educational experiences and needs of higher education students with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(1), 31-41.

Dekker, M. (2000). On our own terms: Emerging autistic culture. Retrieved 12th April 2007, from http://autisticculture.com/index.php?page=articles

Disability Discrimination Act 1992 (Aus). Retrieved from https://www.legislation.gov.au/Series/C2004A04426

Dworzynski, K., Ronald, A., Bolton, P., & Happe, F. (2012). How different are girls and boys above and below the diagnostic threshold for autism spectrum disorders? Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 51(8), 788– 797.

Harmon, A. (2004). How about not ‘curing’ us, some autistics are pleading. Retrieved 23rdOctober 2018 from https://www.nytimes.com/2004/12/20/health/how-about-not-curing-us-some-autistics-are-pleading.html

Johnson, K. (2018). Beyond boy and girl: Gender variance in childhood and adolescence. In L. O’Dell, C. Brownlow, and H. Bertilsdotter Rosqvist (Eds.), Different childhoods: Non/normative development and transgressive trajectories,(pp.25-40). London, England: Routledge.

Kourti, M. & MacLeod, A. (2018). “I don’t feel like a gender, I feel like myself”: Autistic individuals raised as girls exploring gender identity. Autism in Adulthood, 1(1), doi: 10.1089/aut.2018.0001.

Lai, M. C., Lombardo, M. V., Auyeung, B., Chakrabarti, B., & BaronCohen, S. (2015). Sex/gender differences and autism: Setting the scene for future research. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 54(1), 11–24.

Neely-Barnes, S. L., Hall, H. R., Roberts, R. J., & Graff, J. C. (2011). Parenting a child with an autism spectrum disorder: Public perceptions and parental conceptualizations. Journal of Family Social Work,14(3), 208-225.

Ortega, F. (2013). Cerebralizing autism within the neurodiversity movememt. In J. Davidson and M. Orsini (eds.), Worlds of autism: Across the spectrum of neurological difference, (pp.73-96), Minneapolis OH: University of Minnesota Press.

Parsons, S. (2014). “Why are we an ignored group?” Mainstream educational experiences and current life satisfaction of adults on the autism spectrum from an online survey. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 1–25.

Rapley, M. (2004). The Social Construction of Intellectual Disability, Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Richards, G. (1996). Putting psychology in its place. An introduction from a critical perspective. London, England: Routledge.

Rose, N. (1989a). Individualizing psychology. In J. Shotter and K. J. Gergen (Eds.), Texts of Identity,(pp.119-132). London, England: Sage.

Rose, N. (1989b). Governing the soul. The shaping of the private self. London, England: Routledge.

Rose, N. (1990). Psychology as a ‘social’ science. In I. Parker and J. Shotter (Eds.), Deconstructing social psychology. London, England: Routledge.

Taylor, L., Brown, P., Eapen, V., Midford, S., Paynter, J., Quarmby, L., Smith, T., Maybery, M., Williams, K. and Whitehouse, A. (2016). Autism spectrum disorder diagnosis in Australia: Are we meeting best practice standards? Brisbane, Australia: Autism Co-operative Research Centre.

The National Autistic Society. (2016, Mar 31). Can you make it to the end? [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lr4_dOorquQ

The National Autistic Society. (2018, Mar 26). Diverted [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SDXNmRo4CX0&feature=youtu.be

White, B. (2016). The link between autism and trans identity. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2016/11/the-link-between-autism-and-trans-identity/507509/

Widell, V. (2012). Dyslexia. Retrieved from http://geon.github.io/programming/2016/03/03/dsxyliea

Woolhouse, M. (2018). ‘The failed child of the failing mother’: Situating the development of child eating practices and the scrutiny of maternal foodwork. In L. O’Dell, C. Brownlow, and H. Bertilsdotter Rosqvist (Eds.), Different childhoods: Non/normative development and transgressive trajectories,(pp.57-71).London, England: Routledge.