6 Positioning ourselves in multicultural education: Opening our eyes to culture

Renee Desmarchelier

How do we, as teachers, position ourselves in relation to multiculturalism, multicultural policies and education system requirements and expectations?

Key Learnings

- Australian schools are increasingly catering for ethnically and culturally diverse student populations.

- Through recognising that culture is something everyone has, we start to unpack our own attitudes to culture and multicultural education.

- A physical cultural audit collects data in the form of observations and/or photographs of the physical spaces around us and analyses them for the messages they give about the culture/s present in a particular environment.

- Recognising our own cultural postions assists unpacking our own and the education systems expectations and requirements of culturally diverse students.

Understanding ‘culture’ in ‘multicultural’

Culture as a slippery concept

In coming to a chapter considering multicultural education, participants may consider that they have a good understanding of the idea of what multicultural means. However, it is a term that is used extensively within the Australian context, across multiple formal educational settings and quite often in an unproblematic way. There are many policies connecting to the idea of multicultural, such as Queensland’s Multicultural Recognition Act 2016 (Figure 1). Interestingly, the definitions section of this act does not contain a definition of multicultural. Instead it seems to assume that a reader would understand what is implied by this term. It is worth noting that the term diversity in relation to the idea of being multicultural is defined as “cultural, linguistic and religious diversity” (Queensland Multicultural Recognition Act , 2016, p. 5). This chapter contends that in order to understand what is meant by a term such as multicultural, it is first necessary to consider what could be meant by the term culture. As you can see from Figure 6.1, official considerations of the idea of multiculturalism depend upon something termed cultural diversity.

While both the terms culture and multicultural are often presented as simple in their meaning, upon closer investigation, they are complex, slippery and hard to pin down. While ‘common sense’ understandings exist in the public consciousness, to critically engage with multicultural education we need to interrogate these ideas a little further.

Often, particularly within the context of policy documents and ideas around multicultural education, the idea of culture depends on the original nationality or country of origin of a group of people. This might extend not only to where a person was born but also to where their parents and/or grandparents were born. It might refer to a whole national context or a regional area within a particular nation. The tie here is to ethnicity as a way of defining cultural diversity.

Linguistic diversity is also often considered to be part of multicultural considerations (as seen in the Queensland Multicultural Recognition Act, 2016). Language and culture exist in a complex relationship where they are both expressions of each other. If we consider culture to be related to shared values and beliefs of a given group, one way in which these are expressed and communicated is through language. Language development is influenced by culture and while two individuals from different communities may share a language, they may not necessarily share the same understanding of the use of particular word/phrases.

Sometimes, culture is represented through physical artefacts, clothing or symbols, as well as artistic representations such as painting (e.g., on the didgeridoo on the left) and music. Often these are linked to certain traditions, ceremonies or cultural activities with embedded implicit, as well as explicit, meanings. Superficial consideration of a particular culture through its physical representations can result if the intricacies of a particular tradition/representation are not well understood. There is danger in physical representations being misunderstood and feeding into stereotypical ideas/ideals of what a particular culture might be like, particularly if considered in isolation.

In many celebrations of diversity, food is central to displaying and sharing groups’ differing cultural backgrounds. Diverse communities come together to experience each other’s cultures through consuming dishes that are considered to be representative of traditional ways of eating. Food is related to the natural environment, local knowledges about cultivation and gathering, religious beliefs, methods of preparation, norms of how meals are shared and how/when specific foods might be able to be consumed. Again, the interconnectedness of food and culture is more complex than it may seem on the surface and perhaps difficult to grasp through one-off or limited experiences (particularly if isolated from a cultural context).

Underlying the markers of culture are less tangible aspects of culture that relate to how cultural groups relate to each other, develop societal expectations and norms. While food, flags, festivals, language and art might provide visible markers, they do not of themselves constitute a particular culture. Concepts such as peoples’ roles related to their age, notions of family and notions of self are influenced by culture as are approaches to social situations such as treatment of elders, raising of children and the importance of individuals and community.

So, what does ‘multicultural’ mean?

In the public consciousness, the meaning of being multicultural most often relates to peoples’ cultural backgrounds, largely defined by ethnicity (particularly in relation to being non-Anglo-Australian) and living together in a particular society. What this ‘looks like’ and how (or if) it is best achieved can differ substantially according to an individual’s position on issues such as who should/has the position of privilege; what is acceptable and not acceptable in terms of cultural expression; should sameness be the goal or should difference be celebrated; and do particular groups have the right to make decisions in their own best interests?

Steinberg and Kincheloe (2009, pp. 4-5) describe different manifestations of multiculturalism:

a) Conservative diversity practice and multiculturalism or monoculturalism:

- privileges Western patriarchal culture;

- promotes the Western canon as a universally civilising influence;

- has often targeted multiculturalism as an enemy of Western progress;

- sees the children of the poor and non-white as culturally deprived; and

- attempts to assimilate everyone capable of assimilation to a Western, middle-/upper-middle-class standard.

b) Liberal diversity practice and multiculturalism:

- emphasises the natural equality and common humanity of individuals from diverse race, class, and gender groups;

- focuses attention on the sameness of individuals from diverse groups;

- argues that inequality results from a lack of opportunity;

- maintains that the problems individuals from divergent backgrounds face are individual difficulties, not socially structured adversities;

- claims ideological neutrality on the basis that politics should be separated from education; and

- accepts the assimilationist goals of conservative multiculturalism.

c) Pluralist diversity practice and multiculturalism:

- shares many values of liberal multiculturalism but focuses more on race, class, and gender differences than similarities;

- exoticises difference and positions it as necessary knowledge for those who would compete in a globalised economy;

- contends that school curriculum should consist of studies of various divergent groups;

- promotes pride in group heritage; and

- avoids the use of the concept of oppression.

d) Left-essentialist diversity practice and multiculturalism:

- maintains that race, class and gender categories consist of a set of unchanging priorities (essences);

- defines groups and membership in groups around the barometer of authenticity (fidelity to the unchanging priorities of the historical group in question);

- romanticises the group, in the process erasing the complexity and diversity of its history;

- assumes that only authentically oppressed people can speak about particular issues concerning a specific group; and

- often is involved in struggles with other subjugated groups over whose oppression is most elemental (takes precedence over all other forms).

e) Critical diversity and multiculturalism:

- focuses on contextual issues of power and domination;

- promotes critical pedagogy as a way of understanding how educational institutions work in terms of power;

- makes no pretense of neutrality, as it honours the notion of egalitarianism and the elimination of human suffering;

- rejects the assumption that education provides consistent socioeconomic mobility for working-class and non-white students;

- identifies what gives rise to race, class and gender inequalities;

- formulates modes of resistance that help marginalised groups and individuals assert their self-determination and self-direction;

- is committed to social justice and the egalitarian democracy that accompanies it; and

- examines issues of privilege and how they shape social and educational reality.

Understanding our own culture to understand ‘Others’

One of the aspects of culture that has become increasingly important, and therefore far more intensely researched or investigated, is that of dominant and subordinate relationships between cultures. It is important to realise that whilst this material talks about cultures, as if it is possible to clearly identify and contain specific cultures, as if there are certain homogeneities or commonalities that allow distinctive cultures to be identified and named, each person experiences culture in their own idiosyncratic way. That is, despite the need for the purposes of this chapter to talk about cultures as if they are internally consistent, by no means is this the case in the lived experience of people. For example, to talk about Greek culture or Indigenous culture is to perpetuate a very serious error in understanding the fluid and relational aspect of what constitutes culture. However, for the purposes of this chapter, we will work with this sense of broadly monolithic or homogenous cultures.

To say that every person has ‘culture’ potentially casts the individual and their communities as passive recipients and carriers of culture. This perspective ignores the very important fact that we all also create (and re-create) or construct (and re-construct) culture through the very practices of everyday living. As Paulo Freire (2009) pointed out, culture is made by people, and can therefore be remade by people to better serve their emerging needs and purposes. In other words, being ‘cultured’ is a continuously active process, and forms the basis for what we might see as the ongoing development of identity, as well as social change.

Once we understand that everyone has ‘culture’ and that this is not just the province of those who would seem to be culturally different or Other to us, then the focus of areas of study such as anthropology, history, sociology and education in particular broaden considerably to include the culture of those undertaking the enquiry. This has not always been the case. By way of example, anthropology grew as a discipline that had, as its core purpose, to make the seemingly strange cultures of Others understandable to those of Western European backgrounds. In its early days, anthropologists undertook extensive fieldwork in ‘exotic’ locations, attempting to understand the strangeness that they found (or created) there.

The gaze

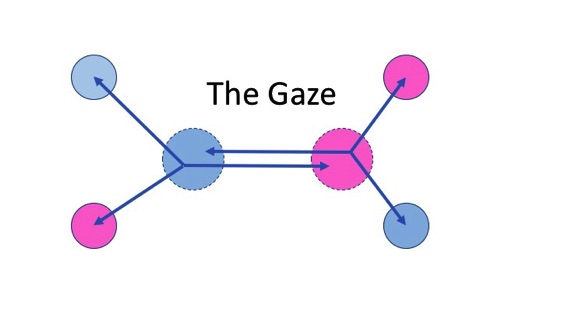

Because we live the large part of our lives within our own primary or home culture, because that culture is the one that we have been born into, educated regarding, and live on a daily basis, each of our own ways of living or being or knowing seem to us to be ‘the way things are’. That is, our own cultural perspective seems to be right or proper, and the way people should aspire and be helped to live. This is because we have grown up and been acculturated into a way of living that we see almost daily as universal or applicable to everyone. Our way is the best way. Those for whom a different cultural context is the norm similarly see the world from that different cultural perspective. The end result is that each of us sees, interprets, and labels cultures other than ours in a particular way whilst at the same time reinforcing views of the acceptability of our own culture. Figure 6.7 represents this:

This diagram attempts to represent a complex process in a graphical way. In it there are two cultures – blue and pink – that are in some relationship with each other. That is, each is aware of the other’s existence, has had some limited experience with that other culture, and each tries to make sense of the other relative to its own standards of right and wrong, normal and deviant, acceptable and unacceptable. The process whereby members of one culture come to observe or in some way try to determine the features of another culture is sometimes called the Gaze. Whilst this term suggests a purely visual process, clearly there are many other sense-based ways in which we come to know about or experience the culture of others – think music and speech (hearing and movement), food (taste and smell) and clothing (touch and sight).

In this diagram, neither of the cultures is clearly bounded or impenetrable. The dotted line boundary around each of the main cultural circles is meant to suggest the fact that no culture is unchanging or impenetrable. The location of the gazing arrows is also important to notice. Both the right-looking and the left-looking arrows start from deep within the blue and the pink circle, that is from deep within the culture doing the looking. However, each arrow only marginally pierces the current boundaries of the other culture, the culture being looked at. This is meant to suggest that the initial Gaze is often largely purely superficial or a first encounter with the other culture and thereby not a deeply experienced and understood encounter with that culture.

What is the impact of ‘the Gaze’? Not only do the formal and informal processes that constitute ‘gazing’ lead to the collection of knowledge about another culture, they also have important impacts upon the culture doing the looking. In the diagram, those cultural workers from within Pink culture will contribute to the ongoing process of developing ‘knowledge’ or ‘the truth’ (and this is a very contested term in this sense) about Blue culture. The promulgation of such information and purported understandings need to be made available to the broader membership of Pink culture. This was the role of the early anthropologists, as mentioned above, and remains a core purpose of ethnographic research today. This continual addition to knowledge about Blue culture is represented by the small blue circle flowing out of the Pink culture circle. In other words, as Pink culture’s understanding of Blue culture spreads through Pink culture, broader community understandings and perspectives on Blue culture become embedded and seen as ‘the truth’ about Blue culture.

At the same time, as members of Pink culture come to understand and ‘know’ other cultures in the world, Pink culture’s view of itself is also impacted upon. Comparisons between what is seen to be the essence of Pink culture are formally and subconsciously culturally compared with those of Blue culture, and typically those comparisons will favour the culture doing the comparison – in this case, Pink culture.

Such a constant comparative process, we would argue, is a continuous one engaged in by all cultural groups at all times. In many ways, this is what the so-called culture industry has as its central educative or public pedagogical purpose: to reflect back to the home culture images of its own essence and worth whilst at the same time presenting comparative ideas and images about those who are different.

In summary, the process of coming to understand Others is one that involves two very distinctly connected developmental characteristics – one, coming to know something about the Other and the second, a process of maintaining or challenging what the gazing culture understands of itself.

As you might imagine, this is also clearly the basis for a fairly universal facet of all cultures, racism (perhaps this term should be more appropriately called culturism). All cultures utilise forms of intellectual abstractions and cultural shorthand to try to capture the infinitely complex aspects of cultures other than their own. Invariably, such reductionisms lead to overly-simplistic, stereotypical attitudes and practices regarding other cultures that are frequently discriminatory and detrimental.

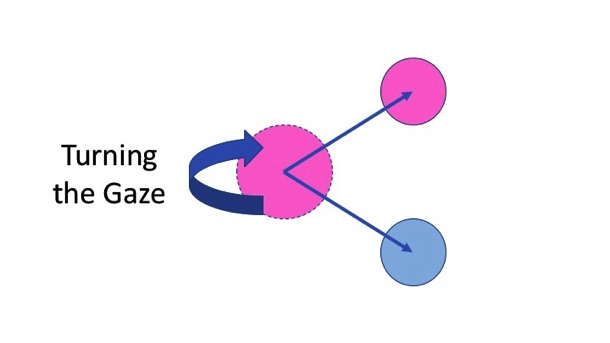

Turning the Gaze back onto Ourselves

For those from a White cultural background, this means looking at how that position privileges us – that is, turning the Gaze this time back upon ourselves (Figure 6.8) in order to try to understand how our cultural location(s) set us up for benefit or advantage, and how our particular ways of seeing and making sense of the world influences the way we see, position and treat Others.

The whole question of belonging to a particular cultural group revolves around two important aspects of identity. One of these is the identity and identification we claim for ourselves: we self-identify as white Australian, Anglo-Australian, Aboriginal Australian, and so forth. But, as the discussion about the operation of the Gaze above exposes, we are also identified BY others as well. Whilst we see ourselves in particular ways, others see us in ways that might sometimes fit with those ways or, at least as frequently, differ considerably from how we see ourselves. What is important here is that it is the power of the dominant group, through its direction of views of community members, to be able to formulate a view of Self and Others that is so powerful and embedded so deeply within the dominant culture that these views become universalised – they become ‘commonsensical’ ‘natural’ statements about the way people are.

Reflection

- Make a list of five words you would associate with the word ‘white’.

- Write a parallel list of words you associate with ‘black’.

- Compare your lists. Can you suggest the ways in which colours convey something about cultural preferences and senses of inadequacy or deficit?

So, what does this all mean for multicultural education?

In order to be able to approach the question of the appropriate ways to work with multiple cultures through education, we need to be genuinely determined to include the dominant culture as one of those cultures being investigated. In other words, a genuine multicultural education in contemporary Australian society must, of necessity, focus on white culture and its impact, as well as on non-white or marginalised cultures. Examples of the types of things such a focus might include in an education sense would be to look at the ways in which whiteness is normalised. This can be achieved through the interrogation of the everyday, such as asking why the tuckshop serves certain food, or where the knowledge base for a certain subject comes from. How whiteness is conflated with ‘human nature’ – and how this renders those who don’t share the characteristics of white culture as being deviant from a norm is unfortunately the most common outcome of much that passes as multicultural or cultural diversity education at present – the view of cultural difference as cultural deficit or cultural deviance (deviance here meaning deviating from the White norm). An interrogation of the ways in which white culture re-embeds and reasserts its superiority over other cultures and similarly the implied inferiority or subordination of other cultures to such superiority can be seen as a necessary starting point in the development of any genuinely culturally aware and respectful person. In other words, it is essential to understand Self in order to understand others.

Watch

The Physical Cultural Audit Process (4.57 minutes)

The Physical cultural audit process

As Brazilian educator, Paulo Freire (2009), pointed out, culture is something that is made by people. He contrasted the cultural with the natural. The natural, he said, is virtually a given, with natural objects being largely unable to be modified in a significant way by people (clearly, his thoughts about this, written in the late 1960s and early 1970s, weren’t able to foresee the impact of human technologies such as genetic modification and the like). When we go looking for evidence of the ‘type’ of people living in a particular area or community or the dominant culture of that particular place, there are several sorts of evidence we draw upon to hazard some guesses about the nature of that community and those people within it. We could look at the ways in which people interact with each other in that community, or at particular images of that community that people create and display through more permanent recording methods (books, movies, music, and various things that would be generally accepted as cultural products or artefacts).

A starting point in trying to come to terms with what sort of community we are looking at could well be the physical or built environment, that is, the non-natural aspects of a landscape that are clearly the result of human activity. It is this approach to developing an initial feel for or understanding of a particular community that we investigate here.

What does the Physical Cultural Audit process involve?

Imagine coming across a landscape where you seem to be the only human being around, something like a Twilight Zone scenario where you’re the only human left in a place, or a Star Trek episode where you’ve been stranded in a place where you seem to be the only form of life similar to that of the human. What you see around you is all you have to work on in coming to understand and perhaps trying to predict what sort of community this was, and maybe still is. This is the essential mindset that needs to be taken into a physical cultural audit: whilst it would be largely impossible to empty space of all visible human presence, in conducting an audit of this type, we have to imagine the space and the place devoid or emptied of human beings. In other words, the audit – like a stock-take – is an attempt to look at what is present in the environment and try to then construct some possible ideas about the type of people who use this place or space. The audit process involves you in the role of a researcher, trying to piece together various ideas about the place so that you might then move into something of a science-fiction or fantasy writer mode by trying to create a possible, though imagined, understanding of what this particular place might be like were one to be living in it.

There is no one set way to conduct a physical cultural audit, but the following steps seem to cover everything for such a process.

Step 1: Work out the boundaries of your space

For many purposes of conducting a physical cultural audit, the place to be investigated is clearly bounded. For the purposes of this particular exercise, that space could be a school where the boundaries of that space will be clearly defined by fences, or your office space, or your living room. However, in a broader sense, places such as shopping centres, city blocks, and the like also present as sites for an audit.

Step 2: Decide on who

Will you conduct the audit by yourself, or with others? There are benefits to both of these options, most of which are connected to the ideas of outsider and insider research. An insider, in this context, would be someone who is very familiar with the space or place to be audited. Consequently, an outsider is somebody for whom the space is new or very unfamiliar. This type of work conducted by insiders brings the benefit of being able to draw on local knowledge of the space such that the insider researcher or auditor will be in a good position to know where to find certain hidden aspects or at least less visible aspects of the environment that may have relevance to the project. The downside of insider research in this type of project is that sometimes being so familiar with the area or the space means that unnoticed or ‘taken-for-granted’ examples are potentially missed or overlooked. This is where the fresh eyes of an outsider bring a benefit – an outsider, whilst not being overly familiar with the hidden or less obvious parts of the site, will probably look at everything as new or novel, thereby picking up some aspects that a more familiar eye might miss.

An advantage of having more than one person in the audit team is that of being able to engage with each other in on-site discussions about what the particular environment offers or the audit process. The shared experience of having moved around the site while discussing the value of certain parts of that site for the audit process will often lead to a stronger analysis of the particular evidence collected.

Overall – how you choose to conduct this type of audit is a decision you make. In some ways, the ‘ideal’ team might consist of two people, one an insider and one an outsider.

Step 3: Decide on how you will conduct your audit

There are a couple of things to consider here:

- If you’re conducting the audit as a team, will you all walk around the site together or individually at first and then collate your individual notes and impressions later?

- Will you use digital photographs to help record aspects of the site that you find of interest?

- Will you audio record any conversations you might have in your team regarding the initial impressions of the site?

- How many circuits of the site will you make? A useful design here is to make an initial walk around to get a feel for the site followed by a more focused investigation of the site (including photographic recording, etc.) and then a final circuit to confirm the ideas or interpretations you’ve made of the evidence you’ve collected on your second circuit.

Step 4: Conduct the walk-around and recording processes

Some things to perhaps consider regarding this stage:

- Is there a particular day of the week and/or time of day that might provide the best opportunity to collect the type of material you need?

- It is important to bear in mind that you’re looking in this physical cultural audit to capture the physical environment, not the social or human environment. In your recording process, are you able to minimise the presence of people in order to focus on the physical?

- Will you have to arrange permission to enter and/or photograph some parts of the site?

- Will you need an acceptably accurate map of the site? If so, how will this be acquired or developed?

Step 5: Analyse the evidence or data you have collected

In this stage, the auditor or auditors try to draw out the impressions that aspects of the environment captured have made on them with regard to the type of community this site is a part of. The ways in which this type of analysis might be conducted vary, but essentially come down to arriving at answers to the question “What does this image tell me/us about this community?” It should be emphasised here that there are no right or wrong answers with regard to this question, you are looking to draw out a team consensus about the sorts of messages conveyed by each particular image of the site. It would be important to record – either in writing or in audio – the conclusions you or your team arrive at for each of the images, and then for an overall summation of what this site seems to reflect with regard to ‘culture’.

With regard to the physical cultural audit that has been developed as a part of the materials for this chapter, the auditing process was conducted by two insider auditors (we were both familiar with this particular street block), and consisted of an initial and a more focused team walk around the city block involved. The second walk also involved a more professional photographer who was able to make the most of what were sometimes poor lighting conditions. What the team considered to be illustrative examples of ‘culture’ in this area were initially discussed, selected and then photographed, with notes regarding the reasons for selecting the particular images recorded in writing. The team then selected from the total photographic collection a smaller number of images for use with the interactive map. The team analysed, through discussion, each of these images and arrived at a number of points regarding these. A spoken commentary was recorded for each of the images and mounted on the interactive map.

Cultural audit map = https://lor.usq.edu.au/usq/file/0669532e-75e9-4145-a327-2d7b5e5ccbff/2/Cultural_Audit_OpnStreetMap.zip/index.html

Once we recognise the multiple and nuanced ways in which culture manifests in society, we can start considering the assumptions and norms that underlay institutions such as schools and universities as well as the public spaces within our communities. Questions such as, what are the expectations of behaviour in this place? who do I expect to see here? and, what function does this place have? all have answers based in the assumed and sometimes unchallenged norms of a society.

To help us consider the ways in which dominant cultural norms inform actions, activities and identities, Dr Ann Milne suggests the analogy of a child’s colouring-in book:

If we look at a child’s colouring book, before it has any colour added to it, we think of the page as blank. It’s actually not blank, it’s white. That white background is just “there” and we don’t think much about it. Not only is the background uniformly white, the lines are already in place and they dictate where the colour is allowed to go. When children are young, they don’t care where they put the colours, but as they get older they colour in more and more cautiously. They learn about the place of colour and the importance of staying within the pre-determined boundaries and expectations. (Milne, 2013, p.v )

As Milne explains, our educational institutions (and other places in society as well) usually work from this unthinking background of white dominant culture. Recognising this background assists us to understand how the written and unwritten ‘rules’ of institutions and society might impact on people whose backgrounds do not align with this cultural norm. As Milne points out, this background is not neutral and this impacts upon the daily existence of people from culturally non-dominant backgrounds.

ways of considering intersecting cultures

There are several ways of considering how cultures intersect in order to be more culturally inclusive. The first we will explore comes from a Torres Strait Islander perspective through Martin Nakata’s idea of the cultural interface (Nakata, 2008b). Nakata’s work, being from his particular standpoint, can assist us to consider a very Australian context for intersecting cultures and speaks to the relationships between Indigenous and settler peoples and knowledges. Secondly, we can look at how people from dominant cultures might refocus their thinking in order to better consider perspectives from non-dominant cultures through the idea of multilogicality (Kincheloe & Steinberg, 2008).

Nakata’s cultural interface

As introduced in Chapter 3, the cultural interface, as the space where Western and Indigenous ways of knowing meet, can be a place of tension as well as of immense opportunity (Nakata, 2002, 2008a, 2010). From his standpoint as a Torres Strait Islander man, Nakata (2011) conceptualises the cultural interface as the contested space between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples, knowledges and cultures. He describes the ways in which Indigenous peoples have not capitulated to the order of Western knowledge, but have taken up what has been necessary to meet practical needs in people’s life worlds (Nakata, 2010). Working from a cultural interface perspective accepts that knowledge systems are dynamic, evolving constantly in response to change, and embedded within culture. It involves a balance of ensuring continuity while simultaneously harnessing change and using the interaction in a way of working that assists Indigenous interests, upholding the unique distinctiveness as First Peoples (Nakata, 2002).

Nakata’s (2002) notion of the cultural interface becomes a useful way of conceptualising the interactions between Indigenous and Western ways of knowing. Clearly the cultural interface is a place where there is both constant tension and negotiation. To explore this space requires an understanding of different discourses and acknowledgment that conflicts that may arise when discourses compete with traditional ones. A cultural interface perspective requires examining and interrogating all knowledge and practices, reflecting upon conditions for convergence of all these and exploration of issues. The challenge is for people to assume a responsible course in relation to future practice where an Indigenous standpoint is embedded (Nakata, 2002).

Presenting differing ways of knowing and naming the world recognises the discontinuities and convergences of the cultural interface while showing an appreciation and acknowledgement of the presence of Indigenous and non-Indigenous standpoints (Nakata, 2011). Allowing the two knowledge systems to sit side by side without competition also connects with the multilogical epistemic stance described by Kincheloe and Steinberg (2008) as being necessary to non-Indigenous peoples’ understanding of Indigenous knowledges.

Multilogicality

The idea of multilogicality encourages people, particularly those of dominant cultural backgrounds, to look at issues, knowledges, concepts and situations from multiple logics in order to increase the complexity of their understandings. When we access a wide range of perspectives from different cultural backgrounds, there is potential to layer and nuance understanding to develop a critical and complex perceptions that takes into account ways of knowing that may not be our own. In effect, multilogicality offers the opportunity to move from a one-dimensional image like a single photograph to being able to see multiple perspectives like a holographic image (Kincheloe & Steinberg, 2008) adding richness and complexity to our cultural awareness.

In order to work with diverse ways of understanding the world, it is first necessary to see the boundedness of culturally dominant knowledge systems and then embrace multiple cultural viewpoints (Austin, 2011). Here we see the necessity of understanding Milne’s colouring book analogy, without considering the background and lines as actively constructing our perceptions, actions and ideas, it is difficult to consider how different perspectives might come together to form new, multilogical spaces.

Conclusion

So, what does a cultural interface or multilogical approach mean for educators in Australia? How might a more culturally nuanced reading of our spaces contribute to better positioning ourselves as educators?

Reflection

- How can understanding your own cultural position help with how you engage with multiculturalism in the classroom?

- What could the concepts of cultural interface and multilogicality mean for implementing curriculum?

- How can you promote similar understandings of cultural contexts in your students?

In everyday classroom practice, multiple opportunities exist to promote a version of multiculturalism that is not exocitising, marginalising or oppressive. Recognising our own cultural position allows us to see/feel/experience from a more informed perspective opening the possibility for expanding our own and our students’ worldviews. Educators can start by asking questions such as, ‘How might my teaching material be experienced by those who are not from the same culture as me?’ Or, ‘What other cultural perspectives might assist me to provoke curiosity about this topic?’ or ‘How am I making this classroom an inclusive cultural experience for my students?’

The first step in enacting culturally appropriate pedagogies and practices is to recognise your own cultural position in order to not further perpetuate marginalising practices. This can be an incremental and continuing process. It can be a case of once we start opening our eyes with a different outlook, we never see the ‘everyday’ in the same way again. Likewise, bringing this new perspective into our practice can be an ongoing process. Critical reflection on our teaching is essential to continued improvement in practice. We may not get it ‘right’ or perfect every time but this is not a reason to stop reflecting and trying new approaches. To be committed to enabling all students to flourish means knowing yourself, knowing your students and being committed to making a difference.

references

Austin, J. (2011). Decentering the WWW (White Western Ways): enacting a pedagogy of multilogicality. In R. Brock, C. S. Malott, & L. E. Villaverde (Eds.), Teaching Joe L. Kincheloe (pp. 167-184). New York: NY: Peter Lang.

Freire, P. (2009). Pedagogy of the oppressed (30th Anniversary ed.). New York, NY: Continuum.

Kincheloe, J. L., & Steinberg, S. R. (2008). Indigenous knowledges in education complexities, dangers, and profound benefits. In N. K. Denzin, Y. S. Lincoln, & L. T. Smith (Eds.), Handbook of critical and indigenous methodologies (pp. 135-156). Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications.

Milne, B. A. (2013). Colouring in the white spaces: Reclaiming cultural identity in whitestream schools.(Doctoral dissertation, University of Waikato, Hamilton, New Zealand. Retrieved from https://researchcommons.waikato.ac.nz/handle/10289/7868

Nakata, M. (2002). Indigenous knowledge and the cultural interface: Underlying issues at the intersection of knowledge and information systems. IFLA Journal, 28(5-6), 281-291. doi:10.1177/034003520202800513.

Nakata, M. (2008a). Disciplining the savages, savaging the disciplines. Canberra, Australia: Aboriginal Studies Press.

Nakata, M. (2008b). Introduction. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 37(Supplement), 1-4.

Nakata, M. (2010). The cultural interface of Islander and scientific knowledge. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 39, 53-57.

Nakata, M. (2011). Pathways for Indigenous education in the Australian Curriculum framework. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 40, 1-8. doi:10.1375/ajie.40.1.

Steinberg, S. R., & Kincheloe, J. L. (2009). Smoke and Mirrors: More than one way to be multicultural. In S. R. Steinberg (Ed.), Diversity and multiculturalism: A reader(pp. 3-22). New York: NY: Peter Lang.