8 Basic Inventory Procedures

A key component in effective kitchen management is inventory control. By knowing what supplies are on hand at a given time, the manager will be able to plan food orders, calculate food costs since the previous inventory, and make menu item changes if needed. By keeping an eye on inventory, it is possible to note potential problems with pilferage and waste.

Managing inventory is like checking a bank account. Just as you are interested in how much money you have in the bank and whether that money is paying you enough in interest, so the manager should be interested in the value of the supplies in the storeroom and in the kitchen.

An inventory is everything that is found within your establishment. Produce, dry stores, pots and pans, uniforms, liquor, linens, or anything that costs money to the business should be counted as part of inventory. Kitchen items should be counted separately from the front of house and bar inventory and so forth.

Regardless of the size of your operation, the principles of inventory control are the same. In larger operations there will be more people and sometimes even whole teams involved with the various steps, and in a small operation all responsibility for managing the inventory may fall on one or two key people.

Effective inventory control can be broken down into a few important steps:

- Set up systems to track and record inventory

- Develop specifications and procedures for ordering and purchasing

- Develop standards and procedures to efficiently receive deliveries

- Determine the frequency and processes for reconciling inventory

- Analyze inventory data and determine any areas for improvement

Setting Up Systems to Track and Record Inventory

One of the reasons you take inventory is to determine food costs and to work out cost percentages. There are several procedures that simplify finding the value of goods in storage. These techniques are based on keeping good records of how much supplies cost and when supplies were purchased.

The temptation in small operations is to treat inventory control casually. Perhaps there are only one or two people doing the purchasing and they are usually aware of the supplies that are on hand. This doesn’t eliminate the need to track purchases against sales to see if you are managing your costs as well as you can.

Almost all inventory control procedures are time consuming. Moreover, such records must be kept up-to-date and done accurately. Trying to save a few hours by cutting back on the time needed to keep inventory records may be money poorly saved.

The simplest method for tracking inventory is using a spreadsheet. A simple spreadsheet might list all of the products that are regularly purchased, with the current prices and the numbers on hand at the last inventory count. The prices can be updated regularly as invoices are processed for payment, and a schedule can be set to count the product on hand.

In large operations, the systems need to be more sophisticated as there are more people involved. Purchases might be made by a separate department, inventory records might be kept by a storeroom clerk, and the tracking and counting of inventory might be tied to a system using scanners and barcodes, which in turn may be linked with your sales system so that there is always a record of what should be in stock.

No matter the depth of detail used, having a system to track inventory gives managers a good idea of supplies on hand and a tool to use to manage costs.

Incoming Inventory

The primary reason for establishing a consistent method for accepting ordered goods is to ensure that the establishment receives exactly what has been ordered. Errors frequently occur, and unless the quantity and quality of the items delivered are carefully checked against what was ordered, substantial losses can take place. When receiving procedures are carefully performed, mistakes that could cost the restaurant time and money are avoided. In addition, an effective receiving method encourages honesty on the part of suppliers and delivery people.

Invoices

The most important document in determining if the goods received are the goods ordered is the invoice. An invoice is an itemized list of the goods or products delivered to a food preparation premise. An invoice shows the quantity, quality, price per kilogram or unit, and, in some cases, the complete extension of the cost chargeable. Only by carefully comparing and checking can you be sure that the information on the invoice tallies with the products received. This comparison may require that items be weighed and/or counted.

Whenever possible, the receiver should check the invoice against the purchase order or purchase request slips. This will ensure that the quantity and price of the goods shipped match those listed on the order form. If the invoice is not checked against the purchase order when the goods arrive, there is the potential that you will be missing products you need or receive products that were not ordered or are in incorrect quantities.

In addition, the quality of the goods should be determined before they are accepted. For example, boxes of fresh produce and frozen foods should be opened and inspected to ensure quality.

When you are satisfied that the delivery is in order, sign the invoice. In most cases, the invoice is in duplicate or triplicate: you keep the original and the delivery driver retains the other copy or copies. Once you have signed, you have relieved the delivery company of its responsibilities and the supplies now belong to your company. You may, therefore, become responsible for any discrepancies between what is on the invoice and what has been delivered. It is good practice to bring any discrepancies or errors to the attention of the driver and have him or her acknowledge the mistake by signing the invoice. If a credit note is issued, that should also be marked on the invoice by the driver.

Take the signed invoice and give it to whoever is responsible for collecting invoices for the company.

The receiving of deliveries can be time consuming for both the food establishment and the delivery service. Often the delivery people (particularly if they are not the supplier) will not want to wait while these checks are done. In this case, it is important that your company has an understanding with the supplier that faults discovered after the delivery service has left are the supplier’s problems, not yours.

Once the invoices have been signed, put the delivered products in the proper locations. If you are required to track incoming inventory, do so at the same time.

Outgoing Inventory

When a supply leaves the storeroom or cooler, a record must be kept to track where it has gone. In most small operations, the supplies go directly to the kitchen where they are used to produce the menu items. In an ideal world, accurate records of incoming and outgoing supplies are kept, so knowing what is on hand is a simple matter of subtraction. Unfortunately, systems aren’t always that simple.

In a smaller operation, knowing what has arrived and what gets used every day can easily be reconciled by doing a regular count of inventory. In larger operations and hotels, the storage rooms and coolers may be on a different floor than the kitchen, and therefore a system is needed that requires each department and the kitchens to requisition food from the storeroom or purchasing department, much like a small restaurant would do directly from the supplier. In this model, the hotel would purchase all of the food and keep it in a central storage area, and individual departments would then “order” their food from the storerooms.

Requisitions

To control inventory and to determine daily menu costs in a larger operation, it is necessary to set up a requisition procedure where anything transferred from storage to the kitchen is done by a request in writing. The requisition form should include the name and quantity of the items needed by the kitchen. These forms often have space for the storeroom clerk or whoever handles the storeroom inventory to enter the unit price and total cost of each requested item (Figure 1).

In an efficiently run operation, separate requisition forms should be used by serving personnel to replace table supplies such as sugar, salt, and pepper. However, often personnel resist using requisition forms because they find it much easier and quicker to simply enter the storage room and grab what is needed, but this practice leaves no record and makes accurate record keeping impossible. To reduce the possibility of this occurring, the storage area should be secure with only a few people having the right to enter the rooms, storage freezers, or storage refrigerators.

Figure 1: Sample Requisition Form

Date: _____________

Department: Food Service

| Quantity | Description | Unit Cost | Total Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6 #10 cans | Kernel corn | ||

| 25 kg | Sugar | ||

| 20 kg | Ground beef | ||

| 6 each | Pork loins |

Charge to:

Catering Dept.

C. Andrews

Chef

Not only does the requisition keep tabs on inventory, it also can be used to determine the dollar value of foods requested by each department and so be used to determine expenses. In a larger operation where purchases may be made from different suppliers at different prices, it may be necessary to tag all staples with their costs and date of arrival. Expensive items such as meats are often tagged with a form that contains information about weight, cost per unit (piece, pound or kilogram), date of purchase, and name of supplier.

Pricing all items is time consuming, but that time will soon be recovered when requisition forms are being filled out or when the stock has to be given a monetary value. In addition, having prices on goods may help to remind staff that waste is costly.

Inventory Record Keeping

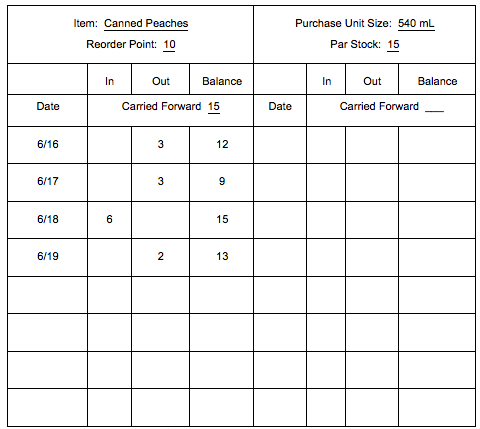

There are two basic record keeping methods to track inventory. The first is taking perpetual inventory. A perpetual inventory is simply a running balance of what is on hand. Perpetual inventory is best done by keeping records for each product that is in storage, as shown in Figure 2.

When more of the product is received, the number of cans or items is recorded and added to the inventory on hand; when some of the product is requisitioned, the number going out is recorded and the balance is reduced. In addition, the perpetual inventory form can indicate when the product should be reordered (the reorder point) and how much of the product should ideally be on hand at a given time (par stock).

In small operations, a perpetual inventory is usually only kept for expensive items as the time (and cost) of keeping up the records can be substantial.

The second inventory record keeping system is taking a physical inventory. A physical inventory requires that all items in storage be counted periodically. To be an effective control, physical inventory should be taken at least monthly. The inventory records are kept in a spreadsheet or in another system reserved for that purpose.

The inventory sheet (Figure 3) can list the items alphabetically or in the order they will appear on the shelves in the storage areas.

Figure 3: Physical Inventory Form

| Product | Unit | Count | Unit Price | Total Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lima beans | 6 #10 | 4 1/3 | $23.00 | $99.60 |

| Green beans | 6 #10 | 3 5/6 | 28.95 | 110.98 |

| Flour | 25 kg bag | 3 | 14.85 | 44.55 |

| Rice | 50 kg bag | 1 | 32.50 | 32.50 |

| Total | $593.68 |

In addition to the quantity of items, the inventory usually has room for the unit cost and total value of each item in storage. The total values of the items are added together to give the total dollar value of the inventory. This is also knows as extending the inventory. The total value of the inventory is known as the closing inventory for the day the inventory was taken. This amount will also be used as the opening inventory to compare with the next physical inventory. If the inventory is taken on the same day of each month, the figures can be used to accurately determine the monthly food cost.

The physical inventory is used to verify the accuracy of the perpetual inventory. For example, if 15 whole beef tenderloins are counted during a physical inventory, but the perpetual inventory suggests that there should be 20 tenderloins on hand, then a control problem exists and you need to find the reason for the variance.

Computerized Inventory Control

Most people today use computerized systems to calculate, track, and extend inventory. These systems enable the restaurant to have a much tighter and more accurate control over the inventory on hand and the costs of that inventory. Having access to information such as ordering history and the best price paid is just one of the benefits of these systems. They can also help the purchaser predict demand levels throughout the year. These programs in many cases are also integrated with the point-of-sale (POS) system used to track sales, and can even remove an item from a computerized inventory list when the waiter registers the sale of any menu item on the restaurant terminal. That is, if a customer orders one chicken dish from the menu, all the items required to make one portion of the chicken are discounted from inventory. This provides management with an constant up-to-date perpetual inventory of most inventory items.

Smaller operations will use a spreadsheet application to manage inventory, so you should also be familiar with a program like Microsoft Excel if you are responsible for ordering and inventory. The information required for the program to do the calculations properly is available from the invoices received with your supplies. That is, the quantities and prices of the goods you most recently received should be entered into the computer program either by you or by the restaurant’s purchaser. These prices and quantities are automatically used to calculate the cost of the goods on hand. This automated process can save you an enormous amount of time and, if the information entered into the computer is accurate, may also save you money. In any inventory system, there is always a possibility for error, but with computerized assistance, this risk is minimized.

Pricing and Costing for Physical Inventory

The cost of items purchased can vary widely between orders. For example, cans of pineapple might cost $2.25 one week, $2.15 the second week, and $2.60 another week. The daily inventory reports will reflect the changes in price, but unless the individual cans have been marked, it is difficult to decide what to use as a cost on the physical inventory form.

There are several different ways to view the cost of the stock on the shelves if the actual cost of each item is difficult to determine. Most commonly, the last price paid for the product is used to determine the value of the stock on hand. For example, if canned pineapple last cost $2.60 a can and there are 25 cans on hand, the total value of the pineapple is assumed to be $65 (25 x $2.60) even though not all of the cans may have been bought at $2.60 per can.

Another method for costing assumes the stock has rotated properly and is known as the FIFO (first-in first-out) system. Then, if records have been kept up-to-date, it is possible to more accurately determine the value of the stock on hand.

Here is an example showing how the FIFO system works.

Example 10

The daily inventory shows the following:

| Date | Number and value of cans |

|---|---|

| Opening inventory, 1st of month | 15 cans @ $2.15 = $32.25 |

| Received on 8th of month | 24 cans @ $2.25 = $54.00 |

| Received in 15th of month | 24 cans @ $2.15 – $51.60 |

| Received on 23 of month | 12 cans @ $2.60 – $31.20 |

If the stock has rotated according to FIFO, you should have used all of the opening inventory, all of the product received on the 8th, and some of the product received on the 15th. The 25 remaining cans must consist of the 12 cans received on the 23rd and 13 of the cans received on the 15th. The value of these cans is then

12 cans @ $2.60 = $31.20

13 cans @ $2.15 = $27.95

Total = $59.15

As you can see, the choice of costing method can have a marked effect on the value of stock on hand. It is always advisable to use the method that best reflects the actual cost of the products. Once a method is adopted, the same method must be used consistently or the statistical data generated will be invalid.

Costing Prepared or Processed Items

When you are building your inventory forms, be sure to calculate the costs of any processed items. For instance, sauces and stocks that you make from raw ingredients need to be costed accurately and recorded on the spreadsheet along with purchased products so that when you are counting your inventory you are able to reflect the value of all supplies on the premises that have not been sold.

(We will discuss more about calculating the costs of products and menu items later in this book.)

Inventory Turnover

When accurate inventory records are kept, it is possible to use the data in the records to determine the inventory turnover rate. The inventory turnover rate shows the number of times in a given period (usually a month) that the inventory is turned into revenue. An inventory turnover of 1.5 means that the inventory turns over about 1.5 times a month, or 18 times a year. In this case, you would have about three weeks of supplies in inventory at any given time (actually 2.88 weeks, which is 52 weeks ÷ 18). Generally, an inventory turnover every one to two weeks (or two to three times per month) is considered normal.

A common method used to determine inventory turnover is to find the average food inventory for a month and divide it into the total food cost for the same month. The total food cost is calculated by adding the daily food purchases (found on the daily receiving reports) to the value of the food inventory at the beginning of the month and subtracting the value of the food inventory at the end of the month.

That is,

average food inventory = (beginning inventory + ending inventory) ÷ 2

cost of food = beginning inventory + purchases − ending inventory

inventory turnover = (cost of food) ÷ (average food inventory)

Example 11

A restaurant has a beginning inventory of $8000 and an ending inventory of $8500. The daily receiving reports show that purchases for the month totalled $12,000. Determine the cost of food and the inventory turnover.

Cost of food = $8000 + $12 000 − $8500 = $11 500

Average food inventory = ($8000 + $8500) ÷ 2 = $8250

Inventory turnover = $11 500 ÷ $8250 = 1.4

The turnover rate in the example would be considered low and would suggest that the business has invested too much money in inventory. Having a lot of inventory on hand can lead to spoilage, high capital costs, increased storage space requirements, and other costs.

Inventory turnover rates are not exact, for a few reasons. One is that in many food operations, accurate inventory records are usually kept only for more expensive items. Another is that the simple food cost used in the calculation does not truly reflect the actual food cost. (Food costs are discussed in another chapter in this book.) In addition, not all inventory turns over at the same rate. For example, perishables turn over as quickly as they arrive while canned goods turn over more slowly.

Even though turnover rates are not exact, they do give managers at least a rough idea of how much inventory they are keeping on hand.

Image Descriptions

Figure 2 Image description: A sample perpetual inventory form for canned peaches.

| Date | In | Out | Balance |

|---|---|---|---|

| June 16 | None | 3 | 12 |

| June 17 | None | 3 | 9 |

| June 18 | 6 | None | 15 |

| June 19 | None | 2 | 13 |

Total goods in stock at any one time.

The direct cost of food.

A document indicating the amount owed for goods or services.

The individual responsible for accepting and checking deliveries.

A document indicating the approval of a quantity of goods ordered from a supplier.

A system of tracking product as it is received and used, thereby keeping a running total of items on hand

Maximum amount of an item that should be in stock at any one time.

A physical inventory requires that all items in storage be counted periodically.

Calculating the total value of goods on hand after taking a physical inventory.

The amount of product on hand at the end of the inventory period.

The amount of product on hand at the start of the inventory period.

A computerized system that coordinates customer purchases, sales, and costs through various linked terminals in a business.

To rearrange inventory so that the oldest product is placed in front of newly acquired product.

First in, first out; a system of managing inventory so that the product received first gets used first.

1. Number of times in a period that inventory is turned into revenue.

2. Number of times in a day that a seat is filled.

Physical assets or money used in the production of goods and services.