Understanding Food Labels

Not so long ago, food choices were limited to what could be grown or raised, hunted or gathered. Today, grocery stores offer seemingly infinite choices in foods, with entire aisles dedicated to breakfast cereals and cases filled with a multitude of different yogurts. Faced with so many choices, how can we decide? Taste matters, of course. But if a healthy diet is your goal, so does nutrition. Food labels are our window into the nutritional value of a given food. Let’s examine what we can learn from food labels and how reading them can help us make smart choices to contribute to a healthy diet.

Health Canada regulates the labelling of food products in Canada through the Food and Drugs Act. Regulations published on January 1, 2003 :

- Make nutrition labelling mandatory on most food labels.

- Update requirements for nutrient content claims.

- Permit, for the first time in Canada, diet-related health claims for foods.

Nutrition Labelling[1]

Nutrition labelling is information included on labels of packaged foods about nutrient content. Considering the health impact of foods and effects related to obesity, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, and other conditions, there has been a shift in many countries to mandate and regulate nutrition labelling.[2]

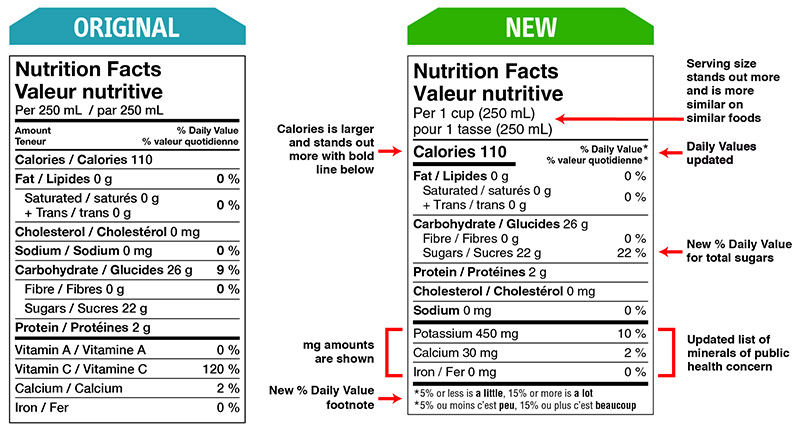

The Canadian government has made efforts to create labels that provide necessary information for consumers. However, it is important to be aware that nutrition labelling is often poorly understood by consumers. Health professionals are expected to be knowledgeable about how to read and interpret nutrition labels (including nutrition facts tables [NFT] and the ingredients list). Such knowledge will allow health professionals to help clients read nutrition labels, like that which is illustrated in Figure 2.1, and to make informed choices about healthy and safe eating that meets the dietary needs of each individual.

Health Canada is responsible for constructing policies to meet the standards set by the Food and Drugs Act (FDA). The Food Directorate of Health Canada is responsible for the “development of policies, regulations and standards that relate to the use of health claims on food”.[3] Other governing bodies, such as the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA), have responsibilities for administering and enforcing food labelling policies as well as managing the Consumer Packaging and Labelling Act. Under this legislation, food producers must meet governmental labelling requirements.

Most prepackaged food labels (e.g., can of soup, bag of chips, bag of frozen peas) must include:

- the NFT,

- a list of ingredients,

- allergen statements,

- and best before dates.

The NFT is mandatory on prepackaged foods with the exception of some items such as alcoholic beverages and products that have few nutrients (e.g., coffee and spices). The Government of Canada[4] does not require nutritional labelling on foods such as fresh fruits and vegetables and foods sold at farmers’ markets. In general, it is mandatory to show both official languages of Canada (French and English) on labels, with some exceptions (e.g., specialty foods, local foods, test market foods, and shipping containers) as long as the products are not resold to consumers.

The Nutrition Facts Table and Ingredient List

Under Government of Canada[5]regulations, the NFT must provide information about:

- serving size

- calories

- percent daily value (% DV) of nutrients

- core nutrients

Currently, the requirements for nutrient information are changing and industry has five years to make changes so that NFT include: fat, saturated fat, trans fat, cholesterol, sodium, carbohydrate, fibre, sugars, protein, potassium, calcium, and iron (Government of Canada, 2019a; Government of Canada, 2017).

Figure 2.2 illustrates the new NFT as compared with the original (i.e., the previous version).

The NFT displays the % DV so consumers can determine the amount of a certain nutrient in one serving. For example, the Government of Canada[6] indicates that 5% of the DV or less of a nutrient is considered “a little” while 15% of the DV or more of a nutrient is considered “a lot.” You should be aware that the % DV is not used to identify whether a person has had sufficient nutrients in a day, particularly considering that many foods do not require the NFT.[7]Rather, it is best to talk with your clients about using the % DV to compare and make choices between different types of food that are higher in healthy nutrients (e.g., fibre) and lower in nutrients that are not healthy (e.g., sodium and trans fat)[8]

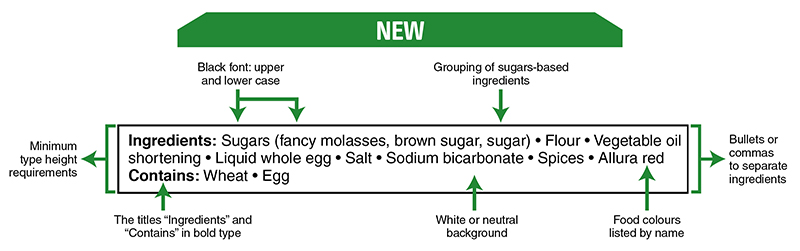

The list of ingredients (as illustrated in Figure 2.3) is mandatory on most packaged foods that contain more than one ingredient, and ingredients are listed in order of weight. The weight of ingredients listed will be an important aspect of your conversation with a client. You may choose to draw their attention to that aspect of food labelling and discuss with them how it might impact their food choices. In addition, caffeinated energy drinks require that the amount of caffeine is included with a statement that the product is a “high source of caffeine” and “not recommended for children, pregnant/breastfeeding women” [9]

Reading Labels

- Statement of identity (what type of food is it?)

- Net contents of the package (how much is in there?)

- Name and address of manufacturer (where was it produced?)

- Ingredients list (what ingredients are included in the food?)

- Nutrition information (what is the amount of nutrients included in a serving of food?)

Statement of Identity

The statement of identity and net contents of the package tell you what type of food you’re purchasing and how much is in the package. The name and address of the manufacturer are important if there’s a food recall due to an outbreak of foodborne illness or other contamination issue. Given the size of our food system and the fact that one manufacturer may make products packaged under multiple brand names, being able to trace a food’s origin is critical.

The last two types of required information—the ingredients list and the nutrition information—are a bit more complex and provide valuable information to consumers, so let’s look more closely at each of these parts of a food label.

By law, food manufacturers must also list major allergens, which include milk, egg, fish, crustacean shellfish, tree nuts, wheat, peanuts, and soybeans.2 Allergens may be listed in a separate statement, as on the corn muffin mix label, which lists “Contains: Wheat” on the label. Alternatively, allergens can be listed in parentheses within the ingredient list, such as “lecithin (soy).” Some labels include an optional “may contain” or “made in shared equipment with…” statement that lists additional allergens that could be present, not as ingredients in the food, but in trace amounts from equipment contamination. For people with food allergies, having this information clearly and accurately displayed on food packages is vital for their safety.

VIDEO: Reading Food Labels[10]

Health Claims

Health claims are statements on food packaging that link the food or a component in the food to reducing the risk of a disease. Health claims can be “authorized” or “qualified.” Authorized health claims have stronger scientific evidence to back them than qualified health claims.

As an example of an authorized health claim, a food that is low in sodium (per the FDA’s definition of less than 140 mg per serving) can include the following claim on their packaging: “Diets low in sodium may reduce the risk of high blood pressure, a disease associated with many factors.”

For an authorized health claim to be approved by the FDA, the agency says “there must be significant scientific agreement (SSA) among qualified experts that the claim is supported by the totality of publicly available scientific evidence for a substance/disease relationship. The SSA standard is intended to be a strong standard that provides a high level of confidence in the validity of the substance/disease relationship.”[11] In other words, the FDA requires a great deal of evidence before allowing food manufacturers to claim that their products can reduce the risk of a disease. As is evident in the low sodium claim, they also require careful language, such as “may reduce” (not definitely!) and “a disease associated with many factors” (as in, there are many other factors besides sodium that influence blood pressure, so a low sodium diet isn’t a guaranteed way to prevent high blood pressure).

Qualified health claims have some evidence to support them, but not as much, so there’s less certainty that these claims are true. The FDA reviews the evidence for a qualified claim and determines how it should be worded to convey the level of scientific certainty for it. Here’s an example of a qualified health claim: “Scientific evidence suggests but does not prove that eating 1.5 ounces per day of most nuts (such as name of specific nut) as part of a diet low in saturated fat and cholesterol may reduce the risk of heart disease.”

Structure-Function Claims

Health claims are very specific and precise in their language, and they convey the level of scientific certainty supporting them. In contrast, structure-function claimsare intentionally vague statements about nutrients playing some role in health processes. Examples of structure-function claims are “calcium builds strong bones” and “fiber maintains bowel regularity.” Note that these statements make no claims to prevent osteoporosis or treat constipation, because structure-function claims are not allowed to say that a food or nutrient will treat, cure, or prevent any disease.[12] They’re allowed by the FDA, but not specifically approved or regulated, as long as their language stays within those rules.

Structure-function claims were originally designed to be used on dietary supplements, but they can also be used on foods, and they’re usually found on foods that are fortified with specific nutrients. They are marketing language, and because nutrients are involved in so many processes, they really don’t mean much.

As you look at food labels, pay attention to what’s shown on the front of the package compared with the back and side of the package. Nutrient and health claims are usually placed strategically on the front of the package, in large, colorful displays with other marketing messages, designed to sell you the product. But for consumers trying to decide which product to buy, you’ll find the most useful information by turning the package around to read the Nutrition Facts panel and ingredients list. These parts of the label may appear more mundane, but if you understand how to read them, you’ll find that they’re rich in information.

Self-Check:

Chapter Attribution

Unit 1, Understanding Food Labels in Nutrition: Science and Everyday Application by Alice Callahan, Heather Leonard, and Tamberly Powell; Lane Community College, published in 2021 under a CC BY-NC license.

- Nutrition and Labelling for the Canadian Baker by go2HR and is used under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. ↵

- (Viola, Bianchi, Croce, & Ceretti, 2016). ↵

- Government of Canada, 2016, 3rd para). ↵

- (2019a) ↵

- (2019a) ↵

- (2019b) ↵

- Government of Canada, 2019b ↵

- (Government of Canada, 2019b). ↵

- (Canadian Food Inspection Agency, 2015). ↵

- Cincinnati Children’s. (May 9, 2019). YouTube. https://youtu.be/tB7BgszxLs8?si=KpLeRIrA16n_mU5o ↵

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2018). Questions and Answers on Health Claims in Food Labeling. FDA. http://www.fda.gov/food/food-labeling-nutrition/questions-and-answers-health-claims-food-labeling ↵

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2018). Structure/Function Claims. FDA. Retrieved from http://www.fda.gov/food/food-labeling-nutrition/structurefunction-claims ↵

Information included on labels of packaged foods about nutrient content.

Information on nutrition labels about serving size, calories, nutrients, and the percent daily value of nutrients.

The amount of a certain nutrient in one serving.

Statements on food packaging that link the food or a component in the food to reducing the risk of a disease.

Claims that have stronger scientific evidence to back them than qualified health claims.

Claims that have some evidence to support them, but not as much, so there’s less certainty that these claims are true.

Vague statements about nutrients playing some role in health processes; not regulated by the FDA.