3 Understanding Customer Behaviour

Learning Objectives

In this chapter, you will learn:

- Conceptual tools for understanding your customer

- Key concepts for thinking about your target audience

- Some Behavioural economic theories

- How digital has affected customer behaviour

Introduction

Although marketing is a business function, it is primarily an exercise in applied human psychology. The role of marketing is to address customer needs and provide value. In either case, success requires a nuanced understanding of how people think, process and choose within their environment.

To achieve this, one must strike a balance between awareness of global shifts and impacts on people’s behaviour and the fiercely intimate motivations that determine where individuals spend their time and money. This chapter outlines an approach for understanding customer behaviour and introduces some conceptual tools used to frame and focus how you apply that understanding to your marketing efforts.

Key Terms and Concepts

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Attention economy | The idea that human attention is a scarce commodity i.e. seeing attention as a limited resource. |

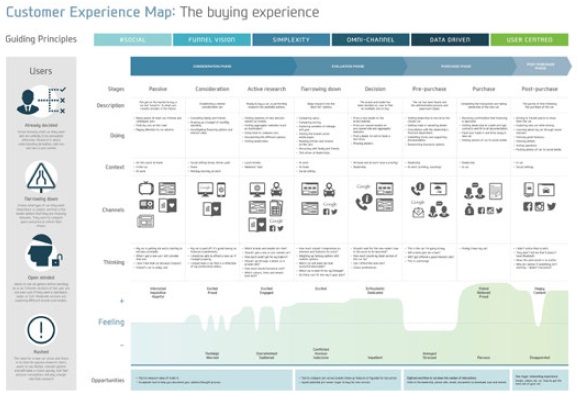

| Customer experience map | A visual representation of the customers’ flow from beginning to end of the purchase experience, including their needs, wants, expectations and overall experience. |

| Customer persona | A detailed description of a fictional person to help a brand visualise a segment of its target market. |

| Global citizen | A person who identifies as part of a world community and works toward building the values and practices of that community. |

| Tribe | A social group linked by a shared belief or interest. |

| Product | An item sold by a brand. |

| Story | A narrative that incorporates the feelings and facts created by your brand, intended to inspire an emotional reaction. |

Understanding Customer Behaviour

The study of consumer behaviour draws on many different disciplines, from psychology and economics to anthropology, sociology and marketing. Understanding why people make the decisions they do forms part of a complex ongoing investigation.

Marketing and product design efforts are increasingly focusing on a customer- centric view. Rather than making people want stuff, successful organisations are focused on making stuff people want. Given the plethora of options, product or service attributes, pricing options and payment choices available to the connected consumer today, competition is fierce and only the considered brand will succeed. Understanding the consumers’ behaviour lies at the heart of offering them value.

Consider that no point of engagement with your brand occurs in isolation for your customer. Their life events, social pressures and motivations impact on their experience with your brand. Something happened before and after they bought that box of cereal and their experience with it does not start or end at the point of sale.

Key Digital Concepts Influencing Customer Behaviour

The Impact of Digital

Digital disruption, which is discussed throughout this book, can appear in many small and large ways. If there’s one thing the past 10 years has taught us, it’s that there is constant disruption and upheaval in the digital world. How we communicate with one another, how we shop, how we consume entertainment and ultimately how we see ourselves in the world, have all changed because of digital. And these changes are continuing, even accelerating.

One of the results of digital tools and media is a destabilising of the status quo. All industries are vulnerable to change when a product or service comes along that meets user needs in an unprecedented way. Netflix has disrupted the media industry; Airbnb has changed travel; and Uber has dramatically impacted what individuals can expect from transport options.

Consider that people born after 1985, more than half the world’s population, have no idea what a world without the Internet is like. They only know a rapid pace of advancement and some tools that serve them better than others.

The Internet seeks no middlemen. Established industries or organisations can be bypassed completely when people are placed in control. Your customers can find another option with one click and are increasingly impatient. They are not concerned with the complexity of the back end. If Uber can offer them personalised cash-free transportation, why can’t your product offer something comparable? People will use the service that best serves them, not what best serves an industry or existing regulations.

The Global Citizens and their Tribe

Coupled with these empowered digital consumers, who are changing digital and driving disruption as much as digital is changing them, is the contradiction evident in the relationship between a global citizen and increasingly fragmented and differentiated tribes built around interests. National identity, given global migration and connectivity, has shifted as the world has gotten smaller. On the other hand, the Internet has created space for people to create, form, support and evolve their own niche communities. This duality forces marketers to keep cognisant of global shifts while tracking and focusing on niche communities and specific segments within their market.

The Attention Economy

The attention economy is a term used to describe the large number of things competing for customer attention. Media forms and the mediums through which they can be consumed have exploded over the last decade and it’s increasingly difficult to get the attention of those you are trying to reach. Your customer is distracted and has many different things vying for their attention.

Tools for Understanding your Customer

Despite the complexity of the customer landscape, various tools and frameworks are available to consider your customer. The goal with many of these is to inform your decision making and help you think from the perspective of your customer.

Developing User Personas

To understand all your customers, you must have an idea of who they are. While it’s impossible to know everyone who engages with your brand, you can develop representative personas that help you focus on motivations rather than on stereotypes.

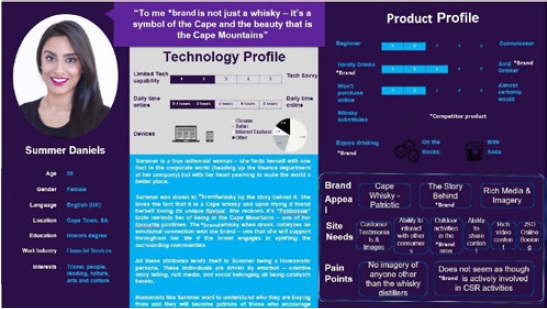

A user persona is a description of a brand-specific cluster of users who exhibit similar behavioural patterns in, for example, their purchasing decisions, use of technology or products, customer service preferences and lifestyle choices. We will revisit the user persona at multiple points during this course, as it shouldn’t be seen as an end in itself.

A user persona is a consensus-driving tool and a catalyst that can be applied when you try to understand your entire customer experience, or when you decide on the implementation of specific tactics. Every organisation should have four to five user personas to help strategists target their efforts.

To create a user persona and inform decisions with your customers’ point of view, one must prioritise real information over your team’s assumptions and gut feelings.

Desktop research, drawn from sources such as existing reports and benchmarking studies, help you to frame the questions you need to ask when delving deeper into the data available to you elsewhere through online platforms like your website or social media presence. The Internet provides an increasing number of viable alternatives to offline primary research.

A combination of habits and specific needs are combined into a usable overall picture. A key feature of the user persona below is how it accounts for customer motivation. Summer is driven by emotion, rich storytelling and social belonging. This knowledge should drive how the brand communicates with her and how her brand experience is tailored to make her feel like part of a community.

To build a robust user persona, you should consider the demographics, psycho- graphics and motivators for your customers.

Demographics and Psychographics

Understanding customers can involve two facets:

- Understanding the physical facts, context and income of their ‘outer world’ i.e. their demographics

These include their culture, sub cultures, class and the class structures in which they operate, among other factors. - Understanding the motives, desires, fears and other intangible characteristics of their ‘inner world’ i.e. their psychographics.

Here we can consider their motives, how they learn and their attitudes.

Both facets above are important, though some factors may be more or less prominent depending on the product or service in question. For example, a women’s clothing retailer needs to consider gender and income as well as feelings about fashion and trends equally, while a B2B company typically focuses on psychographic factors, as their customers are linked by a job function rather than shared demographics.

Demographics can be laborious to acquire but are generally objective and unambiguous data points that change within well-understood and measurable parameters. For example, people get older, incomes increase or decrease, people get married or have children. Data sources like censuses, surveys, customer registration forms and social media accounts are just a few places where demographic data can be gathered either in aggregate or individually.

Psychographics, on the other hand, are fluid, complex and deeply personal because, after all, they relate to the human mind. This information is very hard to define, but when complementary fields work together, it’s possible for marketers to uncover a goldmine of insight.

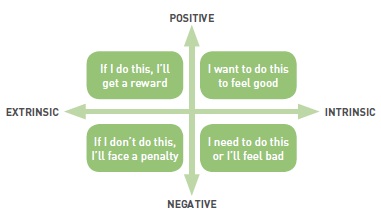

Understanding Motivation

People make hundreds of decisions every day and are rarely aware of all of the factors that they subconsciously consider in this process. That’s because these factors are a complex web of personal motivating factors that can be intrinsic or extrinsic and positive or negative.

Extrinsic Motivators

Extrinsic factors are external, often tangible, pressures, rewards, threats or incentives that motivate us to take action even if we don’t necessarily want to. For example, a worker in a boring or stressful job may be motivated to keep going by their pay check and drivers are motivated to obey traffic rules by the threat of getting a fine or hurting someone.

Marketing often uses extrinsic motivators to provide a tangible reward for taking a desired action. Some examples include:

- Limited-time specials and discounts, where the customer is motivated by a perceived cost saving and the urgency of acting before the offer is revoked.

- Scarcity, where the limited availability of a product or service is used to encourage immediate action.

- Loyalty programmes, which typically offer extrinsic rewards like coupons, exclusive access or free gifts in exchange for people performing desired behaviours.

- Ancillary benefits, such as free parking at the shopping centre if you spend over a certain amount at a specific store.

- Free content or downloads in exchange for contact details, often used for subsequent marketing activities.

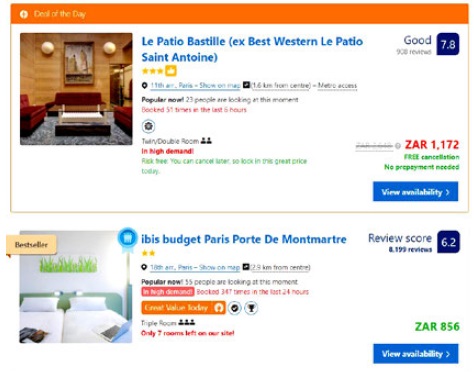

For example, Booking.com uses a range of extrinsic motivators to encourage customers to book quickly, including a price discount exclusive to their site and urgency through the use of the words “High demand”, “Only three rooms left” and, “There are two other people looking at this hotel”. All of these factors nudge the customer to book quickly to avoid missing out on what is framed as a limited-time opportunity.

The problem with extrinsic motivation is that a customer can often perform the desired action to get the reward or avoid the threat without fully internalising the meaning or marketing message behind the gesture. Or worse, the required action becomes ‘work’ which diminishes the enjoyment of the task and the reward.

For example, some people will swipe in at the gym with their membership card to avoid losing their access, but won’t actually exercise. Some might log in to a website every day to accumulate points without actually looking at the specials on offer.

Kohn (1993 ) summarised the three risks of extrinsic rewards as:

- “First, rewards encourage people to focus narrowly on a task, to do it as quickly as possible and to take few risks.

- Second, people come to see themselves as being controlled by the reward. They feel less autonomous and this may interfere with performance.

- Finally, extrinsic rewards can erode intrinsic interest. People who see themselves as working for money, approval or competitive success find their tasks less pleasurable and therefore do not do them as well”.

Intrinsic Motivators

Somebody who is intrinsically motivated performs an action for an intangible benefit simply because they want to, or for the pleasure, fun or happiness of it. Intrinsic motivators are much subtler and more difficult to quantify, but are also more powerful and longer-lasting drivers of human behaviour.

Some common forms of intrinsic motivation include:

- Love – not just romantic love, but also the love of an activity or outcome.

- Enjoyment and fun – few intrinsic motivators are as powerful as the desire to have a good time.

- Self-expression – some people act in a certain way because of what they feel the action says about them.

- Personal values – values instilled through cultural, religious, social or other means can be powerful motivators.

- Achievement or competence – when people challenge themselves, take a meaningful personal risk, or attain a long-desired goal, they are acting because of an intrinsic motivation.

- Negative intrinsic motivators – fear, embarrassment and inertia are some powerful drivers that rely on negative emotions.

Finding the Right Motivators

Many brands develop elaborate marketing campaigns with gimmicks and rewards, but find that these fall flat. Often this is because of a misunderstanding of the motivators that drive customers to take action in the first place. Marketers tend to overvalue how much people like, understand and care about brands, which can lead to a disconnection from the audience.

The most important factor to consider in choosing a customer motivator is relevance to the customer, to the brand and to the campaign. Ask yourself, “Is the incentive you are offering truly relevant and useful?”

Most complex human actions involve a combination of factors. For example, we work because of the external pressure to earn money and some also get an intrinsic reward in the form of achievement, self-expression or making a difference in the world. Both factors are important and if one is missing, the other needs to compensate strongly for this. For example, interns who work for free to get ahead quickly in their careers; people who are paid more to stay in a difficult or unfulfilling job.

The success of your customer persona will depend on how carefully you interrogate assumptions about your customer, how carefully you draw on research and how you prioritise understanding their motivations and the way decisions are made.

Decision Making and Behavioural Economics

One significant shift in understanding customers over the past few years has come from the fields of psychology and economics. This area of inquiry, behavioural economics, looks at what assumptions or behaviours drive decision making. An understanding of individual motivations and interactions between customers and your brand can help you cater to what your market really wants or needs.

As an example, industrial designer Yogita Agrawal designed an innovative and much-needed human-powered light for people in rural India. Although the product ingeniously took advantage of the locals’ mobile lifestyle – the battery is charged through the action of walking – and the idea was well received, initially no one actually used the product. Agrawal eventually discovered the simple reason for this; the device had a plain, ugly casing that did not match at all with the vibrant and colourful local dress. When she added a colourful and personalisable covering to the device, usage shot up dramatically. Although she had found the big insight, that walking can generate energy to power lights in areas not served by the electrical grid, it took a further understanding of regional customs to truly make the device appealing.

If marketers can apply this insight to their strategies and campaigns, it means that they may be able to get more customers to take desired actions more often, for less cost and effort. This is the ideal scenario for any business.

Biases

Cognitive Biases

Cognitive biases are our own personal prejudices and preferences, as well as common ways of thinking that are inherently flawed. A classic example is confirmation bias, where we take note of information that confirms our beliefs or world view, but discount or ignore information that doesn’t.

Try it for yourself! The next time you are driving or commuting, pay attention to all the red cars on the road. Does it begin to seem like there are more red cars than usual?

| Category: | Bias: | Elaboration: |

|---|---|---|

| Information | Knee-jerk bias | Making a quick decision in a circumstance where slower, more precise decision-making is needed |

| Occam’s razor | Assuming that an obvious choice is the best choice | |

| Silo effect | Using a narrow approach to form a decision | |

| Confirmation bias | Only focusing on the information that confirms your beliefs (and ignoring disconfirming information) | |

| Inertia bias | Thinking and acting in a way that is familiar or comfortable | |

|

Myopia bias |

Interpreting the world around you in a way that is purely based on your own experiences and beliefs | |

| Ego | Loss aversion bias | Tending to favour choices that avoid losses, at the risk of potential gains |

| Shock-and-awe bias | Believing that our own intelligence is all we need to make a difficult decision | |

| Overconfidence effect | Having too much confidence in our own beliefs, knowledge and abilities | |

| Optimism bias | Being overly optimistic and underestimating negative outcomes | |

| Force field bias | Making decisions that will aid in reducing perceived fear or threats | |

| Planning fallacy | Incorrectly judging the time and costs involved in completing a task |

Pricing Bias

There is also a lot of bias around the price of an item. Generally, we perceive more expensive to be better and we can actually derive more psychological pleasure from them, even if the cheaper alternative is objectively just as good.

A classic example of this is wine-tasting, where in repeated experiments participants agree that the more expensive wine tastes better where, in fact, all the wines were identical. Taken even further, however, researchers discovered that people tasting the more expensive wines actually had a heightened pleasure response in their brains, showing that researchers could generate more enjoyment simply by telling them they were drinking an expensive wine.[1]

Loss Aversion

One of the most powerful psychological effects is the feeling of loss, when something we possess is diminished or taken away. The negative feeling associated with loss is far stronger than the positive feeling of gaining the equivalent thing. In other words, we feel the pain of losing $200 more acutely that the joy of gaining $200.

Marketers can use loss aversion very effectively in the way they frame and execute marketing campaigns. Here is an example: giving a customer a free trial version of a service for long enough that it becomes useful or important to them at which point they would be happy to pay to avoid losing it. On-demand TV service Netflix uses this to great effect with its 30-day free trial, especially since they ask for credit card details upfront so that shifting over to the paid version is seamless.

Heuristics

A heuristic is essentially a decision-making shortcut or mental model that helps us to make sense of a difficult decision-making process or to estimate an answer to a complex problem.

Some classic examples include:

- The availability heuristic – we overemphasise the likelihood or frequency of things that have occurred recently because they come to mind more easily.

- The representativeness heuristic – we consider a sample to represent the whole, for example in cultural stereotypes.

- The price-quality heuristic – more expensive things are considered to be better quality. A higher price leads to a higher expectation, so this can work both to the advantage and disadvantage of marketers. For products where quality is measurable and linear, the price needs to correlate and a higher price needs to be justified tangibly. For products or services where quality is less tangible or more subjective such as food, drinks, experiences and education, in many ways the price can heighten the perceived quality and experience even on a neurological level.

- Anchoring and adjustment heuristic – we make decisions based on relative and recent information rather than broad, objective fact. In marketing, this can be used to steer customers to the package or offer that the brand most wants them to take.

Choice

How do people choose? This is a difficult question to answer because people decide based on irrational, personal factors and motivators, objective needs and their immediate circumstances.

Word of Mouth or Peer Suggestions

We are very susceptible to the opinions of other people and tend to trust the opinions of friends, family, trusted experts and ‘people like us’ over companies or brands. We are also much more likely to join in on an activity like buying a specific product if we see others like us doing it first. This is the notion of social proof. Human beings generally rely on early adopters to lead the way, with the vast majority waiting for a new product or service to be tested before jumping on board.

This is why many brands use spokespeople or testimonials. They act as a reassurance to the potential customer that other normal people actually experienced the benefits that were promised. This also highlights the importance of positive online word of mouth. As you will learn when we discuss the Zero Moment of Truth, people do extensive research online before important purchases and can have their minds swayed by the reviews, experiences and opinions of others who are often strangers.

Personal Preferences and History

Some of our decisions are based on very personal factors, such as a favourite colour, a positive past experience or a historical or familial association. For example, some people may choose to buy the same brand of breakfast cereal that they remembered eating as a child, regardless of the price or nutritional benefits. For them, the total experience and good feelings form part of the overall value they derive. This is why many brands place emphasis on their long and prestigious histories.

Habits

In other cases, we buy the same thing because we’ve always bought it and it’s simply the easiest option.

Habits are typically triggered by an outside or environmental factor (the cue), which then causes us to act out our habit (the action) after which we receive a positive boost (the reward). This sequence is referred to as the habit loop.

In marketing, the goal is to get a customer to form a habit loop around purchasing or using the brand’s offering. For example, many snack brands try to associate the environmental cues of hunger or boredom with their products such as Kit Kat’s “Have a break” or Snickers’ “You’re not you when you’re hungry” campaigns.

Loyalty programmes can play a key role in helping customers solidify a habit. For example, given the choice of two similar coffee shops on the morning commute to work, a person may be more inclined to visit the one offering a free coffee once they’ve collected a card full of stamps (even if that means going out of their way or paying a bit more for what is essentially a small discount). Eventually, the routine becomes set and it becomes easier to stick to the safe, familiar option.

Here are some examples from brands that encourage habit formation.

| Brand | Cue | Routine | Reward |

|---|---|---|---|

| Starbucks | Walking to work in the morning | Get my regular coffee order | A caffeine hit and a friendly interaction with the barista |

| Nike | Mobile app reminder to go for a run | Put on Nike shoes, go to the gym | Endorphins, satisfaction at living a healthy aspirational lifestyle |

| Movie theatre |

Smell of popcorn | Buy a snack set from the counter | Tasty snack, experiencing the ‘full’ movie-going experience |

How do habits form? To create a habit, you need to perform a repeated action many times in a row. The harder the action such as going for a jog each morning, the longer and more consistently you need to practice the behaviour. Once the habit sets, it becomes a mental ‘shortcut’ that will take conscious effort to override in future.

Decision Load

Making decisions is hard even if the decision is a low-stakes, low-impact one. Generally, psychologists agree that we have a certain quota of decisions that we can make every day, after which subsequent decisions become harder and more taxing and often result in poorer outcomes called ‘decision fatigue’. This is why leading thinkers try to cut out as many trivial decisions as possible. Steve Jobs of Apple famously wore the same blue-jeans-and-turtleneck outfit every day to save himself making that one extra decision every morning.

This is also why we tend to subconsciously eliminate unnecessary decisions and stick to reliable, tested habits. This is especially true for the fast moving consumer goods (FMCG) sector. Consider your habits when buying toothpaste. Typically, you will purchase the same brand you always do without really thinking about it. Unless you had a terrible experience with the product, one toothpaste seems as good as the other, and there’s no incentive to switch. You certainly won’t pause for five minutes in front of the shelf each time to carefully study each option before making your decision. It doesn’t matter enough to get the best one.

Now imagine that your usual brand is out of stock. Suddenly, instead of relying on the existing habit, you are forced to make the decision from scratch at which point marketing factors and price can play an important role. But, crucially, it is the experience that the new product delivers that will be the deciding factor. If the new toothpaste is similar or inferior to the usual brand, there’s no incentive to change the buying habit.

Defaults

Providing a ‘default option’ can be a powerful decision-making shortcut, because it removes the need to make an active decision. Defaults work for a number of reasons.

- They offer a path of least resistance. The default setting is perceived to be the one that is good enough for most people and requires the least amount of thought and customisation. This is ideal for reducing effort.

- They serve as a social signal. The default is seen as the socially approved option. The presumption is that the majority will choose this and there is safety in aligning with the majority.

- They offer assurance. Similarly, we also presume that the default choice has been selected by an expert because of its merit to the end user.

- They take advantage of loss aversion. When it comes to sales and marketing, effective default packages typically include more products or services that are strictly needed to increase the value and therefore the price. This is done simply because opting for a more basic version involves the customer taking elements away and therefore suffering a loss. Once the default price has been anchored in the customer’s mind, there is less incentive to remove unwanted elements, even if the price gets reduced. For example, when buying a new laptop, the customer may be offered a package deal that includes antivirus software, a laptop bag, a wireless mouse and other related accessories.

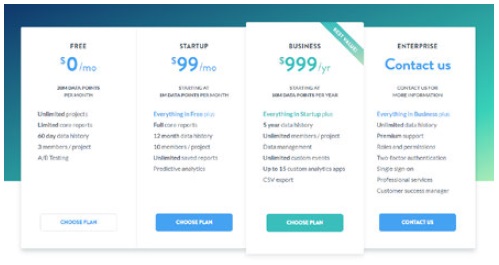

Choice Architecture

You can simplify your customers’ decision-making processes by cleverly designing the choices you offer. This is called choice architecture.

While the following are guidelines only and should be tested thoroughly based on your own individual context, brand and customers, generally speaking a good choice architecture has the following characteristics:

- A small number of choices, usually not more than five, though ideally three. The smaller the number of options to choose from, the easier it is for the customer to distinguish the differences between the options and to avoid a feeling of missing out.

- A recommended or default option. Because people consider expert advice and social preferences when choosing, highlighting one option as ‘the mostpopular choice’ or ‘our top-selling package’ can direct people to the option you most want them to take.

- A visual design hierarchy, typically using colour and size. To make your preferred option stand out, one easy trick is to make it bigger and brighter than the options around it.

Mixpanel strongly emphasises its Business plan as the ideal choice. Not only is it highly emphasised compared to the surrounding options, it includes a ‘best value’ assurance.

Customer Experience Mapping

Once you have carefully crafted personas to guide you around who your customer groups are, you need to understand how and where they are engaging with your brand. This is where customer experience mapping comes into play.

A Customer Experience map visually identifies and organises every encounter a customer has (or could have) with your company and brand. These interactions are commonly referred to as “touchpoints”.[2]

You can use it as a tool to map your entire customer experience, or to drill down into detail for particular parts of that experience. Examples include in-store purchasing or someone trying to buy something on your website.

The map should detail how customers are feeling at various points in their interaction with you and also highlight any pain points that they may be experiencing. Identifying these problems or dips in their experience presents opportunities for engagement and also helps to explain your customer behaviour in context.

Towards Creating your Map

Customer experience maps should vary from business to business, so one shouldn’t just follow a blueprint. Consider the customer journey introduced in Strategy and context, taking someone from consideration through to purchase and hopefully loyalty. The experience map looks at the progression from consideration through to post purchase in great detail and visually synthesises your customer’s behaviour and motivations at every point of contact with your brand. Look at the example above, which includes some key sections:

- Phase – Where is your customer in their interaction with your brand?

- Doing, thinking, feeling – How does what they are feeling and doing vary from stage to stage?

- Channels – What channels or contact points are involved in facilitating this stage of their journey?

- Opportunities – What opportunities exist to solve pain points for your brand?

Measuring Success

The ultimate test of how well you understand your customers is evident in the success of your product or service. Targeted and relevant communications can only drive the sales of a relevant and well-positioned product.

Data on the success of your campaigns, from social media analytics through to site visits and customer service feedback, should both act as measures of success and feed into course correcting your marketing efforts or, where relevant, the nature of your actual product or service.

Every measure and data source discussed throughout the rest of this book should feed into your evolving picture of your customer. Personas and user-experience maps should be living documents and tools.

Case Study: Argos

One-line summary

Leading UK retailer Argos uses data analysis to deliver an overall year-on-year net margin increase of 170%.

The challenge

Argos wanted to increase the effectiveness of their budget and spending and increase revenue from paid search by 30%, without increasing the cost of sales.

The solution

Argos’ marketing agency came up with a six-part strategy to achieve this goal:

- It used predictive analytics models to forecast optimised budget spend and expected revenue for each day, week and month.

- It aligned creative messages with stock and price changes to make sure the right ads were shown to the right people on the right device and at the right time.

- It used a bespoke attribution model to measure the contribution that each click and keyword made to a sale.

- It ran models to see how weather, location, seasonality and other factors caused changes in customer buying behaviour, then synchronised campaigns to those changes.

- It adapted the messaging, scheduling and positioning of paid search ads to take advantage of expected traffic increases after the airing of a TV ad.

- It changed the focus from revenue as a measure of success to profit as a measure of success, so instead of looking only at cost of sale, they examined net margin contribution to product sales.

By reviewing Google data, ROI targets, conversion rates and transactional data, they were able to build predictions for keywords related to over 50000 Argos products. Argos also used software to analyse data from customer-buying triggers like location, weather and TV ads.

Using this data, Argos and their marketing team was able to map season trends across all Argos products, including events like back to school, Argos catalogue launches, Easter, Christmas and more. Using this data, they could anticipate customer demand and predict changes in impressions, clickthrough rate, cost per click and conversion rate.

They used the same software to map weather-dependent products to weather-related digital campaigns for Argos, identifying the effects of temperature on each product all through the year. These seasonal and weather triggers were used in conjunction with daily weather forecasts for each region and store area to automate campaign adjustments and propose bid changes.

Finally, Argos aligned online marketing with TV ad broadcasts for both Argos and competitors, making changes in Google within seconds of an ad being broadcast. This enabled them to take advantage of people who use dual screens while watching TV.Daily diagnostic reports were provided to identify and correct any underperforming campaigns.

Results

The marketing agency delivered a 170% increase year-on-year net margin increase across all product categories. The increase was over 100% in all categories and in some categories as much as 900%. Other results included:•Total annual revenue from search increased by 52% compared to the previous year•PPC delivered a 46% increase on the previous year over Christmas•Web traffic from PPC and Shopping increased by 33% on the previous year•Cost of sales outperformed their target•They lifted conversion rates and average order value•The total number of orders via PPC increased by 31% (Forecaster, n.d).

The Bigger Picture

An understanding of your customer ties to absolutely everything you do in the marketing process. It should inform and drive strategy and aid in matching tactics to outcomes. Feedback on how well you’ve understood your customer can come from various digital channels, social media, conversion optimisation, CRM, data and analytics. While there are many sources of data, only when they are combined into a holistic picture can they help you get to the ‘why’ about your customers.

Summary

People have come to depend on and shape the digital channels that enable connection, individual interest and the disruption of industries. Your consumers are connected, impatient, fickle and driven by a number of motivations and contextual realities. Only through targeting and understanding specifically can you reach them and ensure the success of your brand. Some tools can help you paint a picture of your customers and their experience of your brand by depicting complex motivations, both external and internal. This enables real customer data and research and the ability to consider the complex and sometimes irrational influences on how people make decisions. Customer personas, customer experience maps and the field of behavioural economics can all help to shape your thinking and drive your approach.

Case Study Questions

1.Why did Argos need to use software for this campaign?

2.What kind of data was important for this campaign and how was it collected?

3.What can you learn from the campaign’s use of big data?

Chapter Questions

1.What is behavioural economics?

2.What traps should you avoid when developing a consumer persona?

3.What is the relationship between a consumer experience map that maps your customers’ entire journey and an experience map used in the user experience design discipline?

Further Reading

This presentation offers a good summary of the key topics and ideas within behavioural economics.

Eisenberg, B. and Eisenberg, J., 2006. Waiting for Your Cat to Bark: Persuading Customers When They Ignore Marketing.

References

Eisenberg, B. and Eisenberg, J., 2006. Waiting for Your Cat to Bark: Persuading Customers When They Ignore Marketing. Thomas Nelson Publishers: USA. Forecaster, n.d. Argos Case study. [Online] Available at: www.forecaster.com/argos-case-study[Accessed 27 October 2017]

Kohn, A. (1993). Punished by Rewards: The trouble with gold stars, incentive plans, A’s, praise and other bribes. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Kramp, J., 2011. What is a Customer Experience Map? [Online] Available at: touchpointdashboard.com/2011/08/what-is-a-customer-touchpoint-or-journey-map[Accessed 30 October 2017]

Psychology Today, 2013. Cognitive Biases Are Bad for Business. [Online] Available at: www.psychologytoday.com/blog/the-power-prime/201305/cognitive-biases-are-bad-business[Accessed 30 October 2017]

Risdon, C., 2011. The Anatomy of an Experience Map. [Online] Available at: adaptivepath.org/ideas/our-guide-to-experience-mapping[Accessed 30 October 2017]

Ward, V. 2015. The Telegraph: People rate wine better if they are told it is expensive. [Online] Available at: www.telegraph.co.uk/news/shopping-and-consumer-news/11574362/People-rate-win

Figure acknowledgments

Figure 1. Profile with permission from Mirum, 2017. Image of person, Pixabay, 2018.

Figure 2. Own image.

Figure 3. Screenshot, Booking.com. Date: 23 January 2018. www.booking.com

Figure 4. Screenshot, Mixpanel, 2017. www.mixpanel.com/pricing

Figure 5. Used with permission from Mirum, 2017.