1 An Introduction to Sociology

Learning Objectives

1.1. What Is Sociology?

- Explain the concepts central to sociology.

- Describe the different levels of analysis in sociology: micro-level sociology, macro-level sociology, and global-level sociology.

- Define the sociological imagination.

1.2. Theoretical Perspectives

- Explain what sociological theories and paradigms are and how they are used.

- Describe sociology as a multi-perspectival social science divided into positivist, interpretive and critical paradigms.

- Define the similarities and differences between quantitative sociology, structural functionalism, historical materialism, feminism, and symbolic interactionism.

1.3. Why Study Sociology?

- Explain why it is worthwhile to study sociology.

- Identify ways sociology is applied in the real world.

Introduction to Sociology

Concerts, sporting matches and political rallies can have very large crowds. At such an event, you may feel connected to the group. You are one of the crowd. You cheer and clap when everyone else does. You boo and yell with them. You move out of the way when someone needs to get by. You know how to behave in this kind of crowd.

It can be a very different in an unfamiliar situation. For example, imagine that you are travelling in a foreign country and find yourself in a crowd. You may have trouble figuring out what’s happening. Is the crowd the usual morning rush? Is it a political protest? Perhaps there was an accident or disaster. Is it safe in this crowd, or should you try to get away? How can you find out what is going on? Although you are in it, you may not feel like you are part of this crowd. You may not know what to do.

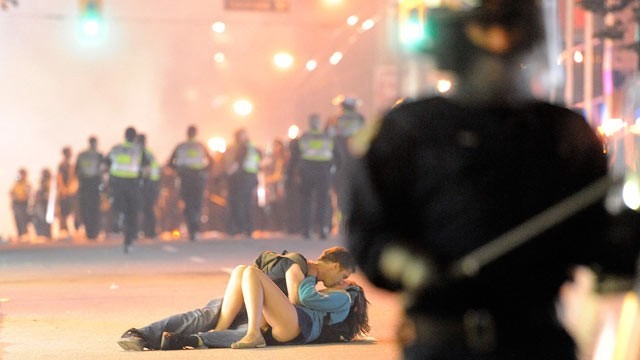

Even within one type of crowd, different groups and behaviours exist. At a rock concert, for example, some enjoy singing along; others prefer to sit and watch. Others join a mosh pit or try crowd-surfing. On February 28, 2010, Team Canada won the gold medal hockey at the Vancouver Winter Olympics. Two hundred thousand happy people filled downtown Vancouver streets to celebrate. Just over a year later, on June 5, 2011, the Vancouver Canucks lost the Stanley Cup to the Boston Bruins. Many people had been watching the game on outdoor screens. Eventually 155,000 people filled the downtown streets. Rioting and looting led to hundreds of injuries, burnt cars, trashed stores. Property damage totaled $4.2 million. Why was the crowd response to the two events so different?

Sociology understands that being in a group changes behaviour. The group is more than the sum of its parts. Why do we feel and act differently in different types of groups? Why might people in a group behave differently in the same situation? These are some questions sociologists ask.

1.1. What Is Sociology?

Sociology is one of the social sciences. Just as natural sciences such as chemistry and geology study the natural world, social sciences study the social world. Other examples of social sciences include economics, political science and anthropology. Sociology studies all aspects of social life using scientific methods.

Sociology is the systematic study of society and social interaction. The word “sociology” comes from the Latin word socius (companion) and the Greek word logos (speech or reason), Together these mean “speech or discourse about companionship”. How can we explain companionship or togetherness?

Social life doesn’t just happen; it is an organized process. Social life can be a brief everyday interaction — moving to the right to let someone pass on a busy sidewalk, for example. Social life can also be larger and ongoing — such as the billions of daily exchanges in the economic system. If there are at least two people involved, there is a social interaction.

- What group processes lead to the decision that moving to the right rather than the left is normal?

- What exchanges and social relationships connect your T-shirt to exploited factory workers in China or Bangladesh?

Sociologists try to answer such questions through research. Sociology uses many theories and research methods to design studies. They apply study results to the real world.

What are Society and Culture? Micro, Macro and Global Perspectives

Sociologists study all aspects and levels of society.

- A society is a group of people whose members interact, live in a definable area, and share a culture.

- A culture includes the group’s shared practices, values, beliefs, norms, and artifacts.

Examples of what sociologists might study:

- analyze videos of people from different societies to understand the rules of polite conversation in different cultures.

- interview people to see how email and instant messaging have changed how they work.

- study the history of international agencies like the United Nations to understand how the world became divided into a First World and a Third World

These examples show how society is studied at different levels of analysis.

- A small-scale example: the detailed study of face-to-face interactions.

- A large-scale example: historical processes affecting entire civilizations.

Sociologists breakdown the study of society into different levels of analysis including micro-level sociology, macro-level sociology and global-level sociology.

Micro-level sociology studies the social dynamics of intimate, face-to-face interactions. An example of micro-level sociology: the study of cultural rules for politeness. Research is conducted with a small group such as family members, work colleagues, or friends. Sociologists might try to understand how people from different cultures interpret each other’s behaviour to see how different rules for politeness lead to misunderstandings. If the same misunderstandings occur many times, the sociologists can suggest ideas about politeness rules to reduce tensions in mixed groups (such as during staff meetings or international negotiations).

Macro-level sociology focuses on large-scale, society-wide social interactions. For example, how does migration affect language use? This is a macro-level sociology because it studies social interaction larger than a small group. These include economic, political, and other circumstances that cause migration; educational, media, and other communication structures that spread of language; class, racial, or ethnic divisions that create slangs or cultures of language; isolation or integration of different communities.

Other examples of macro-level research include examining why women are less likely than men to reach powerful positions in society, or why fundamentalist religious movements are more important in American politics than in Canadian politics. The analysis is not micro-level detail of interpersonal life but larger, macro-level patterns.

Global-level sociology focuses on structures and processes larger than countries or societies: Climate change, introduction of new technologies, investment of capital, cross-cultural conflict,

With the boom and bust of oil, for example, daily life in Fort McMurray is affected not only by relationships with friends and neighbours, not only by provincial and national policies, but also by global markets that determine the price of oil. The context is a global scale of analysis.

The relationship between the micro, macro, and global structures and processes is part of sociology.

The size and methods of sociological studies differ, but sociologists all have two things in common:

- Sociological imagination

- Strict rules about how to do sociological research

The Sociological Imagination

A sociologist looks at society using her sociological imagination. Pioneer sociologist C. Wright Mills (1916-1962) suggested this name for the “sociological lens” or “sociological perspective”.

Mills definition of sociological imagination: how individuals understand their own and others’ lives in relation to history and social structure (1959/2000). Sociological imagination is the capacity to see an individual’s private troubles in the context of the broader social processes that affect them. This allows sociologists to examine “personal troubles” as part of “public issues of social structure” (1959).

Private troubles like unemployment, marital difficulties or addiction can be viewed as only personal, psychological. In an individualistic society like ours, many people will see issues that way: “He has an addictive personality.” “I can’t get a break in the job market.” “My husband is unsupportive” etc. However, widely shared private troubles indicate a common social problem. Common social problems can be caused by how social life is structured. The issues are not understood as simply private troubles. They are best understood as public issues requiring a collective solution. You need sociological imagination to understand them.

Obesity, for example, is recognized as a problem in North America. Michael Pollan says that three out of five Americans are overweight and one out of five is obese (2006). In Canada in 2012, just under one in five adults (18.4%) were obese, an increase from 2003 (Statistics Canada, 2013). Obesity is therefore not simply a private concern related to individual diet or exercise. It is a widely shared social issue that puts people at risk for chronic diseases. It also creates social costs for the medical system.

Pollan argues that obesity is partly caused by the inactive and stressful lifestyle of modern, capitalist society. More importantly, however, it is caused by industrialization of the food chain. Since the 1970s our food chain has produced increasingly cheap and abundant food with many more calories. Cheap additives like corn syrup led to super-sized fast foods and soft drinks in the 1980s. Finding food in the supermarket without a cheap, calorie-rich, corn-based additive is a challenge. The sociological imagination in this example sees the private troubles and attitudes associated with being overweight as a result of the industrialized food chain. This industrialization changed the human/environment relationship — in particular, the types of food we eat and the way we eat them.

By looking at individuals and societies and how they interact, sociologists examine what influences behaviour, attitudes, and culture. Sociologists use the sociological imagination. By applying scientific methods to this process, sociologists can do this without letting their own biases influence their conclusions.

Studying Patterns: How Sociologists View Society

Sociologists are interested in

- the experiences of individuals and

- how those experiences are shaped by interactions with social groups.

To a sociologist, the personal decisions don’t exist in a vacuum. Cultural patterns and social forces put pressure on people to make one choice over another. Sociologists try to identify these general patterns by examining the behaviour of large groups of people who experience the same social pressures. When social patterns persist and become habits, they are referred to as social structures. Persistent social patterns at macro or global levels of interaction are also are described as institutionalized.

One problem for sociologists: Sometimes the relationship between the individual and society is thought of in a moral framework involving individual responsibility and individual choice. Individuals are morally responsible for their behaviours and decisions. Often in this framework, suggesting that an individual’s behaviour needs to be understood in its social context is dismissed as “letting the individual off the hook”.

Social sciences like sociology are neutral on these types of moral questions. Sociologists see the relationship of the individual and society as more complex than the moral framework suggests. Problems need to be studied through evidence-based, not morality-based, research. Sociologists try to see the individual as both a social being and a being who has free choice. Individuals do have responsibilities in everyday social roles. There are social consequences when they fail. But there is always a social context for individual choice and action.

In sociology, the individual and society are inseparable. We can’t study one without the other. German sociologist Norbert Elias (1887-1990) described this through a metaphor of dancing. There can be no dance without the dancers, but there can be no dancers without the dance. Without the dancers, a dance is just an idea about motions in a choreographer’s head. Without a dance, there is just a group of people moving around a floor. Similarly, there is no society without the individuals that make it up, and there are also no individuals who are not affected by the society in which they live (Elias, 1978).

Making Connections: Sociology or Psychology

What’s the Difference?

You might be wondering: If sociologists and psychologists are both interested in people and their behaviour, how are these two disciplines different? What do they agree on, and where do they differ? The answers are complicated but important.

While both disciplines are interested in human behaviour,

- Psychologists focus on how the mind influences that behaviour. Sociologists study how society shapes both behaviour and the mind.

- Psychologists are interested in people’s mental development and how their minds interpret their world. Sociologists are more likely to focus on how different aspects of society contribute to an individual’s relationship with the world.

- Psychologists study inward qualities of individuals (mental health, emotional processes, cognitive processing). Sociologists look outward to qualities of social context (social institutions, cultural norms, interactions with others) to understand human behaviour.

Émile Durkheim (1958–1917) was the first to make this distinction, when he attributed differences in suicide rates among people to social causes (religious differences) rather than to psychological causes (like their mental well-being) (Durkheim, 1897).

Today, we see this same distinction. For example, a sociologist studying how a couple gets to their first kiss on a date might focus on cultural norms for dating, social patterns of romantic activity, or the influence of social background on romantic partner selection. How is this process different for seniors than for teens, for example? A psychologist would more likely be interested in the person’s romantic history, psychological type, or the mental processing of sexual desire.

A sociologist would say that analysis of individuals at the psychological level cannot adequately account for social variability in behaviour: For example, the difference in suicide rates of Catholics and Protestants, or the difference in dating rituals across cultures or historical periods. Sometimes sociology and psychology can combine in interesting ways, however.

1.2. Theoretical Perspectives

Sociologists study social events, interactions, and patterns. Then they develop theories to explain why these occur and what can result from them. In sociology, a theory is a way to explain different aspects of social interactions. Theories also create testable ideas about society (Allan, 2006).

In sociology different approaches and paradigms may offer different explanations. Paradigms are like lenses we look through to see the world. They are philosophical and theoretical frameworks used to make theories, generalizations, and design research. (pronounced “pair a dimes”, like two ten cent coins)

Sociologists use different approaches to knowledge, too. The variety of terms used to describe approaches and paradigms can be confusing. The parable of the wise blind men and the elephant may help. (This parable is adapted from multiple traditional sources including Saxe, 1868 and “Blind men and an elephant,” 2015)

Blind Men and the Elephant

Four wise blind men came across an elephant for the first time in their lives.

The first blind man reached out and touched the elephant’s trunk. “The elephant,” he described, “is like a large flexible tube with a tough hide.”

The second man reached out and found the elephant’s ear. He agreed that the elephant had a tough hide but argued that the first man was wrong. “The elephant is NOT like a long flexible tube but rather like a large, thick leaf.” But he agreed that it had a tough exterior.

The third man approached the elephant’s side and told the first two they were wrong. “Clearly,” the elephant is some huge beast for it goes on beyond my reach in all directions,” he pontificated.

The fourth and final wise man approached the elephant, stretched out his hand, and touched the elephant’s tail. He concluded: “This is like a flexible stick with a tuft of hair on its end, not too different than a large paintbrush.”

Which blind man truly saw the elephant? Did they all, with their different approaches and methods of exploration, see PART of the elephant? What would they need to do to get a complete picture of the elephant? They would need to collaborate about how they looked at the elephant and how they went about measuring the elephant to draw an accurate picture of the elephant.

So it is with sociology and our social world. Different sociologists see our social world from different perspectives (paradigms and approaches to knowledge). Only through collaboration and further scientific study (research methods) can we all come to a clearer picture of our social world.

Sometimes the outcome of research will be different depending on the researcher’s paradigm. Each wise blind man makes a logical description of the elephant, based on their assumptions and experience, but each differs from the others’. Together they describe the whole elephant. Different schools of sociology can explain the same reality in different ways. Together they describe our social world.

Despite sociology’s different perspectives and methodologies, all social research is systematic and rigorous. Sociology is based on scientific research with two key ideas: accurate observation of reality and logical construction of theories.

Three Approaches to Knowledge and Five Paradigms

Sociology is divided into three types of sociological knowledge, each with its own strengths, limitations, purposes, and paradigms (ways of looking at the world):

- Positivist sociology focuses on generating knowledge useful for administering social life

- Interpretive sociology focuses on knowledge useful greater mutual understanding among members of society.

- Critical sociology focuses on knowledge useful for changing and improving the world.

Within these three types of sociological knowledge, there are different paradigms. This book looks at five sociological paradigms: quantitative sociology, structural functionalism, symbolic interactionism, conflict theories, and feminism.

| Positivist Approaches | Interpretive Approaches | Critical Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Quantitative paradigm | Symbolic interactionist paradigm | Conflict theory paradigms |

| Structural-functionalist paradigm | Feminist paradigm |

1. Positivist sociology

The positivist perspective in sociology is like natural sciences such as chemistry and physics. The positivist approach to knowledge emphasizes

- empirical observation (observation through the senses) and measurement

- value neutrality

- the search for law-like statements about the social world (like Newton’s laws of gravity for the natural world)

Just as natural sciences use math and statistics for support, positivism tries to translate human experience into quantifiable units of measurement. Positivism tries to develop knowledge useful for managing social life. Here are two kinds of positivism: quantitative sociology and structural functionalism.

Quantify means to describe in numbers. Quantitative sociology uses statistical methods such as surveys to quantify relationships between social variables. Quantitative sociologists argue that elements of human life can be measured and quantified in essentially the same way natural scientists measure and quantify the natural world. Natural sciences are disciplines like physics, biology, or chemistry.

Researchers analyze data using statistical techniques to uncover patterns or “laws” of human behaviour. For example, the degree of religiosity of an individual in Canada, measured by the frequency of attendance at religious ceremonies, can be predicted by a combination of different independent variables such as age, gender, income, immigrant status, and region (Bibby, 2012).

Structural Functionalism is also a positivist paradigm. Structural functionalism sees society as composed of structures and functions. Structures are regular patterns of behaviour and social arrangements (like the institutions of the family or education). These structures serve functions: the biological and social needs of individuals who make up that society. Society is like a human with different organs. Just like body organs work together to keep the whole system functioning, the various parts of society work together to keep the entire society functioning. Parts of society mean social institutions like the economy, political systems, health care, education, media, and religion.

According to structural functionalism, different social structures perform specific functions to maintain society. These structures define roles and interactions in the family, workplace, church, etc. Functions refer to how the needs of a society (properly socialized children, the distribution of food and resources, or a belief system, etc.) are satisfied.

Different societies have the same basic functional requirements, but they meet them using different kinds of social structures (example: different types of family, economy, or religious practice). So society is seen as a system like the human body or an automobile engine.

For example, the family structure functions to raise new members of society (children), the economic structure functions to adapt to distribute resources, the religious structure functions to provide common beliefs to unify society, etc.

Each social structure provides a specific and necessary function to maintain the whole. If the family fails to effectively raise children, or the economic system fails to distribute resources fairly, or religion fails to provide a good belief system, consequences are felt throughout the system. The other structures need to adapt, causing further change. In a system, when one structure changes, the others change as well.

One structural functionalist, Robert Merton (1910–2003), pointed out that social processes can have more than one function. Manifest functions are the consequences of a social process that intended, while latent functions are the unintended consequences of a social process. Manifest functions of college education, for example, include gaining knowledge, preparing for a career, and finding a good job. Latent functions of college years include meeting new people, participating in extracurricular activities, or finding a spouse or partner. Latent functions can be beneficial, neutral, or harmful.

Criticisms of Positivism

This is the main criticisms of quantitative sociology and structural functionalism: Can social phenomena be studied like the natural phenomena of the physical sciences? Can sociologists study people like chemists study chemicals in a test tube?

Interpretive sociologists say quantification reduces complex of social life to a set of numbers. This loses the meaning social life has for individuals. Measuring religious belief or “religiosity” by the number of times someone attends church explains very little about religious experience. Similarly, interpretive sociology argues that structural functionalism reduces the individual to a sociological robot, without capacity to act or create.

Critical sociologists challenge the conservatism of quantitative sociology and structural functionalism. Both types of positivist approaches say they are objective, or value-neutral. But critical sociology says that the social world is defined by struggles for social justice. Critical sociologists say sociology cannot be neutral or objective.

2. Interpretive Sociology

The interpretive perspective in sociology is a little like literature, philosophy, and history. Interpretative sociology focuses on understanding the meanings humans give to their activity. It is sometimes referred to as social constructivism to describe how individuals construct a world of meaning. This world of meaning affects the way people experience the world. It affects how they behave.

Interpretive sociology promotes the goal of mutual understanding and consensus among members of society.

Symbolic interactionism is one of the main kinds of interpretive sociology. It examines how relationships between individuals in society are based shared understandings. Communication— the exchange of meaning through language and symbols—is how people make sense of their social worlds. This viewpoint sees people shaping their world, rather than as entities who are acted upon by society (Herman and Reynolds, 1994). Symbolic interactionism is a micro-level perspective.

The self develops only through social interaction with others. We learn to be ourselves by interacting with others.

With shared meanings, people find a common course of action. People decide how to help a friend diagnosed with cancer, how to divide up responsibilities at work, or how to resolve conflict. The passport officer at the airport makes a gesture with her hand which you interpret as a signal to step forward pass her your passport. You create a joint action—“checking the passport”— which is just one symbolic interaction in a series for travelers when they arrive at an airport

Social life is seen as the stringing together of many such joint actions. Symbolic interactionism emphasizes that groups of individuals have the freedom and agency to define their situations.

Symbolic-interactionists look for patterns of interaction between individuals. Their studies often involve observation of one-on-one interactions. For example, Howard Becker (1953) studied cannabis users. He argued that the effects of cannabis have less to do with its physical qualities in the body than with the process of communication (or symbolic interaction) about the effects. New cannabis users need to go through three stages to become a regular user: they need to learn from experienced smokers how to identify the effects, how to enjoy them, and how to attach meaning to them (i.e., that the experience is funny, strange or euphoric, etc.). Becker said that smoking cannabis is a social process. The experience of “being high” is as much a product of interactions as it is a bio-chemical process.

Symbolic interactionism has also been important in education about people who are excluded. Howard Becker’s Outsiders (1963), for example, described the process of labelling. Labelling means individuals become labelled as deviants (like criminals) by authorities. A young person, for example, is picked up by police for an offense, defined by police and other authorities as a “young offender,” processed by the criminal justice system, and then introduced to criminal subcultures through contact with experienced offenders. Labelling theory shows that individuals are not born deviant or criminal, but become criminal through symbolic interaction with authorities in institutions. Becker says that deviance is not simply a social fact but the product of a process of definition by authorities and other privileged members of society.Symbolic interactionists prefer qualitative research methods, such as in-depth interviews or participant observation, rather than quantitative methods. They want to understand the symbolic worlds in which research subjects live.

Criticisms of Interpretive Sociology

It can be difficult to make scientific claims about the nature of society from what is learned from small situations, involving very few individuals. While the rich texture of face-to-face social life can be examined in detail, the results will remain descriptive without being able to explain anything. Can we use a particular observation to a general claim about an entire society?

3. Critical Sociology

The critical perspective in sociology comes from social activism, social justice movements, and revolutionary struggles. Karl Marx said its focus was the “ruthless critique of everything existing” (Marx, 1843). The key elements of this critical sociology

- critique of power relations

- understanding society as historical — subject to change, struggle, contradiction, instability, social movement, and radical transformation.

Sometimes critical sociology is called conflict theory. Critical sociology looks at developing knowledge and political action to change power relations. Historical materialism, feminism, environmentalism, anti-racism, and queer studies are examples of critical sociology.

Critical sociology wants to do more than understand or describe the world. It also wants to use sociological knowledge to improve the world and free people from servitude.

The critical tradition in sociology is not about complaining or being “negative.” It’s not about judging people. Sociologist Herbert Marcuse (1964) says critical sociology involves two value judgments:

- Human life is worth living, or that it should be worth living; and

- Possibilities exist to better human life.

Critical sociology does not try to be objective or neutral. Critical sociology promotes social change by using objective knowledge gathered by research. Can you see the difference?

Making Connections: Sociology in the Real World

“Wanna go for a coffee?”

An example of using sociology in everyday life: Think about all the social relationships involved in meeting a friend for coffee. A sociologist could study the social aspects of this event at a micro- level: conversation analysis, dynamics of friend relationships, addiction issues with caffeine, consumer preferences for different beverages, beliefs about caffeine and mental alertness, etc.

A symbolic interactionist might ask: Why is drinking coffee at the center of this interaction? What does coffee mean for you and your friend who meet to drink it?

Critical sociology would note how having coffee involves a series of relationships with others the environment that are not obvious if the activity is viewed in isolation (Swift, Davies, Clarke and Czerny, 2004).

When buy a coffee, we are involved with

- the growers in Central and South America. We are involved with their working conditions and the global structures of private ownership and distribution that make selling coffee profitable.

- the server who works in the coffee shop;

- changes in supply, demand, competition, and market speculation that determine the price of coffee;

- marketing strategies that lead us to identify with beverage choices and brands;

- modifications to the natural environment where the coffee is grown, through which it is transported, and where, finally, the paper cups and other waste are disposed of, etc.

- Ultimately, over our cup of coffee, we find ourselves in a long political and historical process:

- low wage or subsistence farming in Central and South America,

- the transfer of wealth to North America,

- resistance to this process like the fair-trade movement.

Although we are unaware of the web of relationships that we have entered into when we have coffee with a friend, a systematic analysis would see that our casual chat over coffee as the tip of the iceberg. Our relationships involve economic and political structures every time we have a cup of coffee.

Feminism

Feminism is another important kind of critical sociology. Feminist sociology focuses on the power relationships and inequalities between women and men. Patriarchy refers to social structures based on the belief that men and women are different and unequal. Patriarchy has affected property rights, access to positions of power, access to income and many other social structures.

Gender refers to how a society defines attitudes and behaviour considered “proper” for women and men. Gender is different from biological differences between women and men.

Patriarchy has this attitude: physical sex differences between males and females are related to differences in their character, behaviour, and ability. These differences are used to justify a gendered division of social roles and inequality in access to rewards, power and privilege.

Feminist sociology asks: How does giving different qualities to women and men continue the inequality between the sexes? How is the family, law, jobs, religious institutions, etc. organized based in inequality between the genders?

There are many kinds of feminism. Despite the differences, feminist approaches have four things in common:

- Gender differences are the central focus.

- Gender relations are viewed as a social problem. There are social inequalities and stress.

- Gender relations can be changed. They are sociological and historical in nature, so there can be change and progress.

- Feminism wants to change the conditions of life that are oppressive for women.

Criticisms of Critical Sociology

The radical nature of critical sociology is criticized. Critical sociology wants revolutionary transformation of society, and not everybody agrees.

Critical sociology is also criticized for exaggerating the power of dominant groups to manipulate groups with less power. For example, media representations of women are said to portray unrealistic beauty standards and make women sex objects. This suggests that women are controlled by media images and have little ability to interpret media images for themselves. Similarly, interpretive sociology challenges critical sociology for implying that people are products of large historical forces rather than individuals who can act to help themselves.

Because social reality is complex, different sociological approaches can see the social world differently. Is society characterized by conflict or agreement? Is human practice determined by external social structures or is it the product of human choice and action? Is human experience unique because of social interaction, or can it be studied like the physical world of chemistry? The answer to each question is: Both answers are correct! Different sociological perspectives allow better insights into social experience.

Making Connections: Sociological Research

Farming and Locavores: How Sociological Perspectives Might View Food Consumption

Eating is a daily activity, but it can also be associated with important moments in our lives. Eating can be an individual or a group action, and culture influences eating habits and customs. In the context of society, social movements, political issues, and economic debates address our food system. Any of these might become a topic of sociological study.

A structural-functional approach to food consumption might be interested in the role of the agriculture industry within the nation’s economy. Or how human systems adapt to environmental systems. The structural-functionalist might be interested in disequilibrium in the human/environment relationship caused by population increases and the industrialized agriculture. — from the early days of manual-labour farming to modern mechanized agribusiness. The idea of sustainable agriculture, promoted by Michael Pollan (2006) and others, shows changes needed to return interaction between humans and the natural environment to equilibrium.

A symbolic interactionist would be more interested in micro-level topics: the shared meaning of food, like as symbolic use of food in religious ceremonies, attitudes towards food in fast food restaurants, the role of food in the social interaction of a family dinner. This perspective might also study group interactions of those who identify themselves based on a diet, such as vegans (people who do not eat meat or dairy products) or locavores (people who try to eat locally-produced food).

A critical sociologist might be interested in the power differentials in the regulation of the food industry. They might explore where people’s right to information intersects with corporations’ drive for profit and how the government mediates this. Critical sociologists might also be interested in the power and powerlessness experienced by local farmers versus large farming corporations. In the documentary Food Inc., the plight of farmers resulting from Monsanto’s patenting of seed technology is depicted as a product of the corporatization of the food industry. Another topic of study might be how nutrition and diet vary between different social classes. The industrialization of the food chain has created cheaper foods than ever. However, this may result in the poorest people eating food with the least nutrition.

1.3 Why Study Sociology?

How has sociology affected Canadian society?

Think of the Canadian health care system. The Nova Scotia health care plan has many problems, but can you imagine life without MSI? Can you imagine paying for every appointment, test and service – or what would happen if you couldn’t pay?

Tommy Douglas introduced the first publicly funded health care plan in Canada in 1961 in Saskatchewan. Many criticized the idea, and doctors went on strike. The Royal Commission on Health Services studied the legislation and its effects. They decided it could work. Sociologist Bernard Blishen (b. 1919) was research director for the Commission. Blishen designed Canada’s national Medicare program in 1964.

Blishen went on to work in the field of medical sociology and created an index to measure socioeconomic status (the Blishen scale). He received the Order of Canada in 2011 for his contributions to the creation of public health care in Canada.

Many sociologists try to understand society, Others see sociology as a way not only to understand, but also to improve society. Besides the creation of public health care in Canada, sociology has contributed to many important social reforms such as

- equal opportunity for women in the workplace,

- improved treatment for individuals with mental and learning disabilities

- increased recognition and accommodation for people from different ethnic backgrounds

- creation of hate crime legislation

- recognition of Aboriginal rights

- prison reform

Sociologist Peter Berger (b. 1929) describes a sociologist as “someone concerned with understanding society in a disciplined way.” Sociologists are interested in the important moments of people’s lives as well as everyday occurrences. Berger also describes the “aha” moment when a sociological theory becomes understood:

[T]here is a deceptive simplicity and obviousness about some sociological investigations. One reads them, nods at the familiar scene, remarks that one has heard all this before and don’t people have better things to do than to waste their time on truisms — until one is suddenly brought up against an insight that radically questions everything one had previously assumed about this familiar scene. This is the point at which one begins to sense the excitement of sociology (Berger, 1963).

Sociology can be exciting because it teaches people how they fit into the world and how others see them. Sociology helps people understand how they connect to groups based on the many ways groups classify themselves and how society classifies the groups. Sociology raises awareness of how those classifications—such as economic and status levels, education, ethnicity, or sexual orientation—affect perceptions and decisions.

Sociology teaches people not to accept easy explanations. It teaches them a way to ask better questions and find better answers. It makes people more aware that there are many kinds of people in the world who do not think the way they do. It increases their ability to try to see the world from other people’s perspectives. This prepares them to live and work in an increasingly diverse and integrated world.

Sociology in the Workplace

Employers want people with “transferable skills.” This means that they want to hire people whose knowledge, skills and education can be applied in a variety of settings and tasks. Studying sociology can provide people with transferable knowledge and skills, including:

- An understanding of social systems and large bureaucracies;

- The ability to devise and carry out research projects to assess whether a program or policy is working;

- The ability to collect, read, and analyze statistical information from polls or surveys;

- The ability to recognize important differences in people’s social, cultural, and economic backgrounds;

- Skill in preparing reports and communicating ideas; and

- The capacity for critical thinking about social issues and problems that confront modern society (Department of Sociology, University of Alabama).

Sociology prepares people for many careers. Besides conducting social research or becoming sociology teachers, sociologists are hired to work in government agencies, nongovernmental organizations, social services, counselling agencies (such as family planning, career, substance abuse), design and evaluate social policies and programs, health services, market research, independent research and polling. Even a small amount of training in sociology is useful in careers like sales, public relations, journalism, teaching, law, nursing, and criminal justice.

Chapter Summary

What Is Sociology?

Sociology is the systematic study of society and social interaction. In order to carry out their studies, sociologists identify cultural patterns and social forces and determine how they affect individuals and groups. They also develop ways to apply their findings to the real world.

Theoretical Perspectives

Sociologists develop theories to explain social events, interactions, and patterns. A theory is a proposed explanation of those patterns. Theories have different scales. Macro-level theories, such as structural functionalism and conflict theory, try to explain how societies operate as a whole. Micro-level theories, such as symbolic interactionism, focus on interactions between individuals.

Why Study Sociology?

Studying sociology helps both individuals and society. Sociology prepares students for careers in an increasingly diverse world. Sociology helps students understand their role in the social world. Sociology teaches us to think critically about social issues. Sociological research helps solve social problems.

Key Terms

capitalism: an economic system. Capitalism favors private or corporate ownership and production/sale of goods in a competitive market.

critical sociology: A theoretical perspective that focuses on inequality and power relations in society. Critical sociology works for social justice.

culture: Includes a group’s shared practices, values, beliefs, norms and artifacts.

feminism: The critical analysis of the way gender differences in society structure social inequality.

functionalism (structural-functionalism): An approach that sees society as a structure with interrelated parts. These parts work together to meet the biological and social needs of individuals.

gender: a society’s definition for attitudes and behaviour considered “proper” for women and men. Gender is different from biological differences.

global-level sociology: The study of structures and processes beyond the boundaries of countries or specific societies.

interpretive sociology: A theoretical perspective that explains human behaviour in terms of the meaning humans give to it.

latent functions: Unintended consequences of a social process.

macro-level sociology: The study of society-wide social structures and processes.

manifest functions: Intended consequences of a social process.

micro-level sociology: The study of specific relationships between individuals or small groups.

paradigms: Philosophical and theoretical frameworks used to make theories, generalizations, and design research.

patriarchy: social structures in which men have most of the power

positivism (or positivist sociology): The scientific study of social patterns based on methods of the natural sciences.

quantitative sociology: Statistical methods such as surveys with large numbers of participants.

society: A group of people whose members interact, reside in a definable area, and share a culture.

sociological imagination: The ability to understand how your own unique circumstances relate to that of other people, as well as to history in general and societal structures.

sociology: The systematic study of society and social interaction.

structural functionalism: see functionalism.

structure: General patterns that persist through time. They become habits at micro-levels of interaction, or institutionalized at macro or global levels.

symbolic interactionism: A theoretical perspective that examine the relationship of individuals in their society by studying communication (language and symbols).

theory: A proposed explanation about social interactions or society

Chapter Quiz

- Which of the following best describes sociology as a subject?

- the study of individual behaviour

- the study of cultures

- the study of society and social interaction

- the study of economics

- Wright Mills once said that sociologists need to develop a sociological __________ to study how society affects individuals.

- culture

- imagination

- method

- tool

- A sociologist defines society as a group of people who reside in a defined area, share a culture, and who:

- interact.

- work in the same industry.

- speak different languages.

- practise a recognized religion.

- Seeing patterns means that a sociologist needs to be able to:

- compare the behaviour of individuals from different societies.

- compare one society to another.

- identify similarities in how social groups respond to social pressure.

- compare individuals to groups.

- The difference between positivism and interpretive sociology relates to:

- whether individuals like or dislike their society.

- whether research methods use statistical data or person-to-person research.

- whether sociological studies can predict or improve society.

- all of the above.

- Which would a quantitative sociologists use to gather data?

- a large survey

- a literature search

- an in-depth interview

- a review of television programs

- Which of these theories is most likely to look at the social world on a micro-level?

- structural functionalism

- conflict theory

- positivism

- symbolic interactionism

- A symbolic interactionist may compare social interactions to:

- behaviours.

- conflicts.

- human organs.

- theatrical roles.

- Which research technique would most likely be used by a symbolic interactionist?

- surveys

- participant observation

- quantitative data analysis

- none of the above

- Studying Sociology helps people analyze data because they learn:

- interview techniques.

- to apply statistics.

- to generate theories.

- all of the above.

- Berger describes sociologists as concerned with:

- monumental moments in people’s lives.

- common everyday life events.

- both a and b.

- none of the above.

Short Answer

-

What do you think C. Wright Mills meant when he said that to be a sociologist, one had to develop a sociological imagination?

-

Describe a situation in which a choice you made was influenced by societal pressures.

-

Which theory do you think better explains how societies operate — structural functionalism or conflict theory? Why?

-

Do you think the way people behave in social interactions is more due to the cause and effect of external social constraints or more like actors playing a role in a theatrical production? Why?

-

How do you think taking a sociology course might affect your social interactions?

-

What sort of career are you interested in? How could studying sociology help you in this career

Further Research

Sociology is a broad discipline. Different kinds of sociologists employ various methods for exploring the relationship between individuals and society. Check out more about sociology: http://www.sociologyguide.com/questions/sociological-approach.php.

People often think of all conflict as violent, but many conflicts can be resolved nonviolently. To learn more about nonviolent methods of conflict resolution check out the Albert Einstein Institution: http://openstaxcollege.org/l/ae-institution.

For a nominal fee, the Canadian Sociological Association has produced an informative pamphlet “Opportunities in Sociology” which includes sections on: (1) The unique skills that set sociology apart as a discipline; (2) An overview of the Canadian labour market and the types of jobs available to Sociology BA graduates; (3) An examination of how sociology students can best prepare themselves for the labour market; (4) An introduction, based on sociological research, of the most fruitful ways to conduct a job search: https://www.fedcan-association.ca/event/en/33/91.

References

Beck, Ulrich. (2000). What is globalization? Cambridge: Polity Press.

CBC. (2010, September 14). Part 3: Former gang members. The current. CBC Radio. Retrieved February 24, 2014, from http://www.cbc.ca/thecurrent/2010/09/september-14-2010.html

Durkheim, Émile. (1951). Suicide: A study in sociology. New York: Free Press. (original work published 1897)

Elias, Norbert. (1978). What is sociology? New York: Columbia University Press.

Mills, C. Wright. (2000). The sociological imagination. (40th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. (original work published 1959)

Office of the Correctional Investigator. (2013). Backgrounder: Aboriginal offenders — A critical situation. Government of Canada. Retrieved February 24, 2014 from http://www.oci-bec.gc.ca/cnt/rpt/oth-aut/oth-aut20121022info-eng.aspx

Pollan, Michael. (2006). The omnivore’s dilemma: A natural history of four meals. New York: Penguin Press.

Simmel, Georg. (1971). The problem of sociology. In D. Levine (Ed.), Georg Simmel: On individuality and social forms (pp. 23–27). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (original work published 1908)

Smith, Dorothy. (1999). Writing the social: Critique, theory, and investigations. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Statistics Canada. (2013). Overweight and obese adults (self-reported), 2012. Statistics Canada health fact sheets. Catalogue 82-625-XWE. Retrieved February 24, 2014, from http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/82-625-x/2013001/article/11840-eng.htm

Allan, Kenneth. (2006). Contemporary social and sociological theory: Visualizing social worlds. Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press.

Becker, Howard. (1963). Outsiders : Studies in the sociology of deviance. New York: Macmillan.

Bibby, Reginald. (2012). A new day: The resilience & restructuring of religion in Canada. Lethbridge: Project Canada Books

Blumer, H. (1969). Symbolic interactionism: Perspective and method. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bryant, Christopher. (1985). Positivism in social theory and research. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Coffee Association of Canada. (2010). 2010 Canadian coffee drinking survey. About coffee: Coffee in Canada. Retrieved May 5, 2015 from http://www.coffeeassoc.com/coffeeincanada.htm.

Davis, Kingsley and Moore, Wilbert. (1944). Some principles of stratification. American sociological review, 10(2):242–249.

Drengson, Alan. (1983). Shifting paradigms: From technocrat to planetary person. Victoria, BC: Light Star Press.

Durkheim, Émile. (1984). The division of labor in society. New York: Free Press. (original work published 1893)

Durkheim, Émile. (1964). The rules of sociological method. J. Mueller, E. George and E. Caitlin (Eds.) (8th ed.) S. Solovay (Trans.). New York: Free Press. (original work published 1895)

Goffman, Erving. (1958). The presentation of self in everyday life. Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh, Social Sciences Research Centre.

Habermas, Juergen. (1972). Knowledge and human interests. Boston: Beacon Press.

Herman, Nancy J. and Larry T. Reynolds. (1994). Symbolic interaction: An introduction to social psychology. Lanham, MD: Altamira Press.

LaRossa, R. and D.C. Reitzes. (1993). Symbolic interactionism and family studies. In P. G. Boss, W. J. Doherty, R. LaRossa, W. R. Schumm, and S. K. Steinmetz (Eds.), Sourcebook of family theories and methods: A contextual approach (pp. 135–163). New York: Springer.

Lerner, Gerda. (1986). The Creation of patriarchy. New York: Oxford University Press.

Marcuse, Herbert. (1964). One dimensional man: Studies in the ideology of advanced industrial society. Boston: Beacon Press.

Martineau, Harriet. (1837). Society in America (Vol. II). New York: Saunders and Otley. Retrieved February 24, 2014 from https://archive.org/details/societyinamerica02martiala

Maryanski, Alexandra and Jonathan Turner. (1992). The social cage: Human nature and the evolution of society. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Marx, Karl. (1977). Theses on Feuerbach. In David McLellan (Ed.), Karl Marx: Selected writings (pp. 156–158). Toronto: Oxford University Press. (original work published 1845)

Marx, Karl. (1977). The eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte. In David McLellan (Ed.), Karl Marx: Selected writings (pp. 300–325). Toronto: Oxford University Press. (original work published 1851)

Marx, Karl. (1978). For a ruthless criticism of everything existing. In R. C. Tucker (Ed.), The Marx-Engels reader (pp. 12–15). New York: W. W. Norton. (original work published 1843)

Mead, G.H. (1934). Mind, self and society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Naiman, Joanne. (2012). How societies work (5th ed.). Black Point, Nova Scotia: Fernwood Publishing.

Parsons, T. (1961). Theories of society: Foundations of modern sociological theory. New York: Free Press.

Schutz, A. (1962). Collected papers I: The problem of social reality. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff.

Smith, Dorothy. (1977). Feminism and Marxism: A place to begin, a way to go. Vancouver: New Star Books.

Spencer, Herbert. (1898). The principles of biology. New York: D. Appleton and Company.

Swift, J., Davies, J. M., Clarke, R. G. and Czerny, M.S.J. (2004). Getting started on social analysis in Canada. In W. Carroll (Ed.), Critical strategies for social research (pp. 116–124). Toronto: Canadian Scholars’ Press.

Weber, Max. (1997). Definitions of sociology and social action. In Ian McIntosh (Ed.), Classical sociological theory: A reader (pp. 157–164). New York, NY: New York University Press. (original work published 1922)

Berger, Peter L. (1963). Invitation to sociology: A humanistic perspective. New York: Anchor Books.

Department of Sociology, University of Alabama. (n.d.). Sociology: Is sociology right for you?. Huntsville: University of Alabama. Retrieved January 19, 2012 from http://www.uah.edu/la/departments/sociology/about-sociology/why-sociology

Vaughan, Frederick. (2004). Aggressive in pursuit: The life of Justice Emmett Hall. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Image Attributions

Figure 1.1. Canada Day National Capital by Derek Hatfield (http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Canada_Day_National_Capital.jpg) used under CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/deed.en)

Figure 1.2. Il (secondo?) bacio più famoso della storia: Vancouver Riot Kiss by Pasquale Borriello (https://www.flickr.com/photos/pazca/5844049845/in/photostream/) used under CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/)

Figure 1.3 Sociologists learn about society as a whole while studying one-to-one and group interactions. (Photo courtesy of Robert S. Donovan/Flickr)

Figure 1.5. People holding posters and waving flags at a protest rally. (Photo courtesy of Steve Herman/Wikimedia Commons)

Figure 1.6. Martini, H.E. (1909). The Blind Men and the Elephant [illustration] (p.87). In Charles M. Stebbins & Mary H. Coolidge (Eds.), Golden treasury readers: Second reader (pp. 87-93). New York: American Book Company. Open Domain Image.

Figure 1.7. Coffee Association of Canada, 2010. (Photo courtesy of Duncan C/Flickr)

Long Description

| Normative | Conflictual | |

|---|---|---|

| Structure | Comte’s Positivism and Durkheim’s Structural Functionalism | Foucault’s Poststructuralism |

| Agency | Weber’s Interpretive Sociology and Mead’s Symbolic Interactionism | Martineau’s Feminism and Marx’s Critical Sociology |

Solutions to Chapter Quiz

[Return to Review Questions]