5 Groups and Organizations

Learning Objectives

- Analyze the operation of a group as more than the sum of its parts.

- Understand primary and secondary groups as two key sociological groups.

- Recognize in-groups, out-groups, and reference groups as subtypes of primary and secondary groups.

- Distinguish between different styles of leadership.

- Explain how conformity is impacted by group membership.

- Distinguish between groups, social networks, and formal organizations.

- Analyze the dynamics of dyads, triads, and larger social networks.

- Categorize the different types of formal organizations.

- Define the characteristics of bureaucracies.

- Analyze the opposing tendencies of bureaucracy toward efficiency and inefficiency.

- Identify the concepts of the McDonaldization of society and the McJob as aspects of the process of rationalization.

- Apply the sociological study of groups and bureaucracies to analyze the social conditions of the Holocaust.

Introduction to Groups and Organizations

A punk band is playing outside. The music is loud, the crowd excited. But neither the lyrics nor the people in the audience are what you might expect. Mixed in with the punks and young rebel students are members of local unions, from well-dressed teachers to casually dressed labour leaders. The band’s lyrics are not published anywhere but are available on YouTube: “We’re here to represent/The 99 percent/Occupy, occupy, occupy.” The song: “Wouldn’t It Be Nice If Every Movement Had a Theme Song” (Cabrel, 2011).

The Occupy movement slogan,“We are the 99%,”refers to the distribution of wealth, with the upper class (the “one percenters”) owning most wealth. Even during the severe economic crisis in 2008, the personal income, bonuses, and wealth of the 1% increased. The people responsible for the crisis were paying themselves bonuses, while they were receiving billions of dollars in bailouts from governments.

Occupy protests occurred in many Canadian cities as well, including Victoria and Montreal. A similar movement, Idle No More, emerged to advocate for Indigenous justice. Idle No More organized according to Indigenous principles of decentralized leadership.

Simply having a grievance does not explain the ways in which movements take form as groups, however. Numerous groups made up the Occupy movement, yet there was no central movement leader. What makes a group something more than just a collection of people? How are leadership functions and styles established in a group? What unites the people protesting from New York City to Victoria, B.C.? Are homeless people truly aligned with law school students? How does a non-hierarchical organization work? How is the social order of a diverse group maintained when there are no formal regulations? What are the stated or unstated rules in such groups? How do members come to share a common set of meanings concerning their movement?

5.1. Groups

What does it mean to be part of a group? The concept of a group is important to society. Society exists in groups. In a group, individuals behave differently than they would if they were alone. They conform, they resist, they cooperate, they betray, they organize, they defer gratification, they show respect, they expect obedience, they share, they manipulate, etc. Being in a group can change behaviour. An important insight of sociology: the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. The group has characteristics over and above the characteristics of its individual members. But how exactly does the whole come to be greater?

Defining a Group

In sociology, a group refers to a collection of

- at least two people

- who interact with some frequency and

- who share a sense identity.

Every gathering is not necessarily a group. An audience watching a busker is a one-time random gathering. People who exist in the same place at the same time, but who do not interact or share a sense of identity — such as a bunch of people standing in line at Tim Horton’s—are a crowd. People who share similar characteristics but are not otherwise tied to one another are considered a category.

An example of a category would be Millennials, the term given to people born from approximately 1980 to 2000. Why are Millennials a category and not a group? Because while some of them share a sense of identity, they do not all interact frequently with each other.

A crowd or category can become a group. During disasters, people in a neighbourhood (a crowd) who did not know each other might become friendly and depend on each other at a local shelter. After the disaster ends, the cohesiveness may last because they all shared an experience. They might remain a group, practising emergency readiness, coordinating supplies for the next emergency, or taking turns caring for neighbours in need. There may be many groups within a single category. Consider teachers, for example. Within this category, groups may exist like teachers’ unions, teachers who coach, or a faculty committee.

Types of Groups

Sociologist Charles Horton Cooley divided groups into two categories: primary groups and secondary groups (Cooley, 1909/1963). Primary groups play the most critical role in our lives. The primary group is usually small. Primary groups consist of individuals who generally engage face-to-face in long-term, emotional ways. This group serves emotional needs: expressive functions rather than pragmatic ones. The primary group is usually made up of significant others—individuals who have the most impact on our socialization. The best example of a primary group is the family.

Secondary groups are usually larger and impersonal. They may be task-focused and time-limited. These groups serve an instrumental function rather than an expressive one, meaning that their role is more goal- or task- oriented than emotional. A classroom or office can be an example of a secondary group.

How are our needs for primary group intimacy altered in the age of electronic media?

Making Connections: Case Study

Best Friends She’s Never Met

Writer Allison Levy worked alone. While she liked the flexibility, she sometimes missed having a community of coworkers, both for the practical purpose of brainstorming and the more social “water cooler” aspect. Levy did what many do in the internet age: she found a group of other writers online. While writers in general represent all genders, ages, and interests, it ended up being a collection of 20- and 30-something women who all wrote fiction for children and young adults.

At first, the writers’ forum was clearly a secondary group united by the members’ professions and work situations. As Levy explained, “On the internet, you can be present or absent as often as you want. No one is expecting you to show up.” It was a useful place to research information about different publishers, find out who had recently sold what, and track industry trends. But as time passed, Levy found it served a different purpose. Since the group shared other characteristics beyond their writing (such as age and gender), the online conversation naturally turned to matters such as childrearing, aging parents, health, and exercise. Levy found it was a sympathetic place to talk about any number of subjects, not just writing. Further, when people didn’t post for several days, others expressed concern, asking whether anyone had heard from the missing writers. It reached a point where most members would tell the group if they were travelling or needed to be offline for a while.

The group continued to share. One member on the site who was going through a difficult family illness wrote, “I don’t know where I’d be without you women. It is so great to have a place to vent that I know isn’t hurting anyone.” Others shared similar sentiments.

On the other hand, Zygmunt Bauman (2004) discusses the way electronically mediated groups like this online web forum tend to be frail communities, “easy to enter and easy to abandon.” They do not substitute for the more tangible and solid “we” feeling of face to face forms of togetherness, which require commitment and risk. Virtual communities “create only an illusion of intimacy and a pretense of community. They are not valid substitutes for ‘getting your knees under the table, seeing people’s faces, and having real conversation.’” They are a version of what Bauman calls cloakroom communities, places where one can hang one’s identity like a cloak for the duration of the “show”– i.e., one’s interest in the group’s theme and interactions — and then collect it again when it’s time to move on.

Is this online writers’ forum a primary group? Most of these people have never met each other. They live in Hawaii, Australia, Minnesota, and across the world. They may never meet. Levy wrote recently to the group, saying, “Most of my ‘real-life’ friends and even my husband don’t really get the writing thing. I don’t know what I’d do without you.” Despite the distance and the lack of physical contact, the group clearly fills an expressive need.

In-Groups and Out-Groups

One of the ways that groups can be powerful is through inclusion, and its opposite, exclusion. In-groups and out-groups are subcategories of primary and secondary groups that include and exclude. Primary groups consist of both in-groups and out-groups, as do secondary groups. The feeling of belonging to a group can be exciting, while the feeling of not being allowed in can be motivating in a different way. Sociologist William Sumner (1840–1910) developed the concepts of in-group and out-group to explain this phenomenon (Sumner, 1906/1959). An individual feels membership to an in-group, and believes it to be an important part of identity. An out-group, conversely, is a group someone doesn’t belong to; often there may be a feeling of dislike or competition with an out- group. Sports teams, unions, and secret societies are examples of in-groups and out-groups; people may belong to or be an outsider.

In-groups and out-groups can explain some negative human behaviour, such as white supremacist movements like the Ku Klux Klan or the bullying of gay or lesbian students. By defining others as “not like us” and inferior, in-groups can practice ethnocentrism, racism, sexism, ageism, and heterosexism—judging others negatively based on their culture, race, sex, age, or sexuality.

Often, in-groups form within a secondary group. For instance, a workplace can have cliques of people, from senior executives who play golf together to young singles who socialize after hours. These in- groups might show favouritism for other in-group members, and the overall organization may be unable or unwilling to acknowledge it. The politics of in-groups may exclude others as a form of gaining status within the group.

Making Connections: Social Policy and Debate

Bullying and Cyberbullying: How Technology Has Changed the Game

Most of us know that “sticks and stones may break my bones, but words will never hurt me” is inaccurate. Words can hurt, and that is very apparent in bullying. Bullying has always existed, often reaching extreme levels of cruelty in children and young adults. People at these stages of life are especially vulnerable to others’ opinions of them, and they’re deeply invested in their peer groups.

Today, technology deepens this dynamic. Cyberbullying is the use of interactive media by one person to torment another, and it’s increasing. Cyberbullying can mean sending threatening texts, harassing someone in a public forum (such as Facebook), hacking someone’s account or identity, posting embarrassing images online, and so on.

The Cyberbullying Research Center found that 20% of middle-school students admitted to “seriously thinking about committing suicide” becasue of online bullying (Hinduja and Patchin, 2010). While bullying face-to-face requires willingness to interact with your victim, cyberbullying allows bullies to harass others from the privacy of their homes without witnessing the damage firsthand. This form of bullying is particularly dangerous because it’s widely accessible and easier to accomplish.

Cyberbullying made international headlines in 2012 when a 15-year-old girl, Amanda Todd, in Port Coquitlam, B.C., committed suicide after years of bullying by her peers, and internet sexual exploitation. A month before her suicide, she told her story in a YouTube video. Bullying began in grade 7 when she had been lured to reveal her breasts in a webcam photo. A year later, when she refused to give an anonymous male “a show,” the picture was circulated to her friends, family, and contacts on Facebook.

Statistics Canada reported that 7% of internet users aged 18 and over have been cyberbullied, most commonly (73%) by receiving threatening or aggressive emails or text messages. Nine percent of adults who had a child at home aged 8 to 17 reported that at least one of their children had been cyberbullied. Two percent reported that their child had been lured or sexually solicited online (Perreault, 2011).

After Amanda Todd’s death, most provinces enacted strict guidelines obliging schools to respond to cyberbullying and encouraging students to come forward to report victimization. In 2013, the federal government proposed Bill C-13—the Protecting Canadians from Online Crime Act—which would make it illegal to share an intimate image of a person without that person’s consent. (Critics, however, note that the anti-cyberbullying provision in the bill is only a minor measure among many others that expand police powers to surveil all internet activity.) Will these measures change the behaviour of would-be cyberbullies? That remains to be seen. But hopefully communities can work to protect victims before they feel they must resort to extreme measures.

Large Groups

It is difficult to define exactly when a small group becomes a large group. One step might be when there are too many people to join in a simultaneous discussion. Another might be when a group joins with other groups as part of a movement that unites them. These larger groups may share a geographic space, such as Occupy Montreal or the People’s Assembly of Victoria, or they might be spread out around the globe. The larger the group, the more attention it can garner, and the more pressure members can put toward whatever goal they wish to achieve. At the same time, the larger the group becomes, the more the risk grows for division and lack of cohesion.

One can think of three main social forms by which the content or activity of a group might be organized to prevent division and lack of cohesion: domination, cooperation, and competition. No matter what the organization is — a hockey franchise, a workplace, or a social movement — the choice of one form of organization over the others has consequences in terms of the loyalty of members and the efficiency and effectiveness of the group in achieving its goals. In the form of domination, power is concentrated in the hands of leaders while the power of subordinates is severely restricted or constrained. In extreme versions of domination, like slavery, loyalty and efficiency are low because fear of coercion is the only motivation. In the form of cooperation on the other hand, power is distributed relatively equally and loyalty and efficiency are high because the group is based on mutual trust and high levels of commitment. In the form of competition, power is distributed unequally but there is latitude for movement based on the outcome of competition for prestige or money. Loyalty and efficiency are relatively high but only as long as the pay-offs are high.

In a Star Trek episode from the 1960s, “Patterns of Force,” the crew of the Enterprise discover that a rogue historian has gone against the Prime Directive and reorganized a planet’s culture on the basis of Nazi Germany. In order to address the planet’s condition of chaos, he appealed to the “efficiency” of Nazism only to unleash a systematic persecution of one native group by the other. The ensuing drama in the episode reveals that the historian mistook domination for efficiency. As Spock puts it at the end of the episode, how could such a noted historian make the logical error of emulating the Nazis? Captain Kirk responds by saying that the failure was in putting so much power in the hands of a dictator, to which Dr. McCoy adds that power corrupts. In fact, as historians point out, Nazi Germany was startlingly inefficient, if only because all major decisions were filtered through Hitler himself who was notoriously unpredictable, hard to get the attention of, and lacked any form of personal routine (Kershaw, 1998). The irony of the Star Trek episode is of course that the Starship Enterprise itself is organized on the formal basis of domination. It is only the leadership style that differs.

Group Leadership

Often, larger groups require formal leadership. Small, primary groups tend to have informal leadership. After all, most families don’t take a vote on who will rule the group, nor do most groups of friends. Leaders do not emerge, but formal leadership is rare.

In a series of small group studies at Harvard in the 1950s, Robert Bales (1970) studied the group processes that emerged around solving problems. No matter what the specific tasks were, he discovered that in all the successful groups—the groups that were able to see complete tasks without breaking up—three types of informal leader emerged: a task leader, an emotional leader, and a joker.

The task leader organized the group to solve the problem by setting goals and distributing tasks. The emotional leader helped the group resolve disagreements and frustrations when strong feelings emerged. The joker made fun but also made jokes had to release group tension. These leadership roles emerged spontaneously in the small groups without planning or awareness. They appear to be characteristics of task-oriented, face-to-face groups.

In secondary groups, leadership is usually more formal. There are often clearly outlined roles and responsibilities, with a chain of command. Some secondary groups, like the army, have highly structured and clearly understood chains of command, and many lives depend on those. How well could soldiers function in a battle if different people were calling out orders? Other secondary groups, like a workplace or a classroom, also have formal leaders, but the styles and functions of leadership vary significantly.

Leadership function refers to the main focus or goal of the leader. An instrumental leader is goal- oriented and largely concerned with accomplishing set tasks. An army general or a company CEO would be an instrumental leader. In contrast, expressive leaders are more concerned with promoting emotional strength and health, and ensuring that people feel supported. Social and religious leaders—rabbis, priests, imams, and directors of youth homes and social service programs—are often perceived as expressive leaders.

There is a stereotype that men are more instrumental leaders and women are more expressive leaders. Although gender roles have changed, even today, many women and men who exhibit the opposite-gender manner are seen as deviants and may encounter resistance. Presidential candidate Hillary Clinton provides an example of how society reacts to a high-profile woman as an instrumental leader. Despite stereotypes, however, Boatwright and Forrest (2000) have found that both men and women prefer leaders who use a combination of expressive and instrumental leadership.

In addition to these leadership functions, there are three different leadership styles.

Democratic leaders encourage group participation in all decision making. These leaders work hard to build consensus before choosing a course of action. This type of leader is common, for example, in a club where the members vote on which activities to pursue. These leaders can be well-liked, but sometimes work will proceed slowly because consensus building is time-consuming. A further risk is that group members might pick sides in opposing factions rather than reaching a solution.

In contrast, a laissez-faire leader (French for “leave it alone”) is hands-off, allowing group members to make their own decisions. An example of this kind of leader might be an art teacher who opens the art cupboard, leaves materials on the shelves, and tells students to help themselves and make some art. While this style can work well with highly motivated and mature participants who have clear goals and guidelines, it risks group confusion and a lack of progress.

Authoritarian leaders give orders and assign tasks. These leaders are instrumental leaders with a strong focus on meeting goals. Often, entrepreneurs fall into this mould, like Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg. Not surprisingly, this type of leader risks alienating the workers. There are times, however, when this style of leadership can be required.

In different circumstances, each leadership style can be effective and successful. Consider what leadership style you prefer. Why? Do you like the same style in different areas of your life, such as a classroom, a workplace, and a sports team?

Making Connections: Case Study

Women Leaders and the Glass Ceiling

Elizabeth May, leader of the Green Party, was voted best parliamentarian of the year in 2012 and hardest-working parliamentarian in 2013. She stands out among national party leaders as both the only woman and the only leader focused on changing leadership style.

She wants to change leadership by reducing centralization and hierarchical control of party leaders, allowing MPs to vote freely, decreasing political partisanship, increasing collaboration, and restoring respect and decorum to House of Commons debates. The focus on collaborative, non-conflictual approach to politics is a component of her expressive leadership style, typically associated with female leadership qualities.

According to some political analysts, women candidates face a paradox: they must be as tough as their male opponents on issues, such as foreign or economic policy, or risk appearing weak (Weeks, 2011). However, the stereotypical expectation of women as expressive leaders is still common.

Many believed Elizabeth May won the 2008 election leaders debate by being firm in her criticism of government policy and being both intelligent and clear in her statements. The idea of winning debates and defeating opponents in a hostile environment is regarded as a masculine virtue. At the same time, May is subject to criticisms that have to do with her femininity, in a way that male politicians are not subject to similar criticisms about their masculinity.

Media tycoon Conrad Black called her “a frumpy, noisy, ill- favoured, half-deranged windbag” to which, May quipped, “He’s right on one point: I certainly am frumpy. I don’t have anything like Barbara Amiel’s [Black’s well-known journalist wife] sense of style. But overall, I figure being attacked by Conrad Black is in its own way an accolade in this country” (Allemang, 2009).

Despite the cleverness of May’s retort, her situation as a female leader reflect broader issues women confront in assuming leadership roles. Even though women have been closing the gap with men in terms of workforce participation and education over the last decades, their average income has remained at approximately 70% of men’s, and men are twice as likely as women to attain leadership roles. In terms of the representation of women in Parliament, cabinet, and political leadership, the figures are much lower at 15% (even though several provinces have had women as premiers) (McInturff, 2013).

One concept for describing women’s access to leadership positions is the glass ceiling. While most of the explicit barriers to women’s achievement have been removed through legislation, norms of gender equality, and affirmative action policies, women still often get stuck at middle management. There is a glass ceiling or invisible barrier that prevents them from achieving leadership positions (Tannen, 1994). This is also reflected in gender inequality in income over time. Early in their careers men’s and women’s incomes are equal but at mid-career, the gap increases significantly (McInturff, 2013).

Tannen argues that this barrier exists in part because of the different work and conversational-style differences styles of men and women. While men are very aggressive in their conversational style and their self-promotion, women are typically consensus builders who seek to avoid appearing bossy and arrogant. As a linguistic strategy of office politics, it is common for men to say “I” and claim personal credit in situations where women would be more likely to use “we” and emphasize teamwork. Since men are often in the positions to make promotion decisions, they interpret women’s style of communication “as showing indecisiveness, inability to assume authority, and even incompetence” (Tannen, 1994).

Women’s expressive leadership, which in many cases is more effective, their skills, merits, and achievements go unrecognized. In terms of political leadership, one political analyst said bluntly, “women don’t succeed in politics—or other professions—unless they act like men. The standard for running for national office remains distinctly male” (Weeks, 2011).

Conformity

We all like to fit in. Likewise, when we want to stand out, we want to choose how we stand out and for what reasons. For example, a woman who loves cutting-edge dresses in new styles likely wants to known for high fashion. She would not want people to think she was too poor to find proper clothes.

Conformity is the extent to which an individual complies with group norms or expectations. We look to groups to assess and understand how we should act, dress, and behave. Not surprisingly, young people are particularly aware of who conforms and who does not. A high school boy whose mother makes him wear ironed, button-down shirts might protest that he will look stupid—that everyone else wears T-shirts. Another high school boy might like wearing those ironed shirts to stand out. This is the contradictory dynamics of fashion: it represents both the need to conform and the need to stand out. How much do you enjoy being noticed? Do you consciously prefer to conform to group norms so as not to be singled out? Are there people in your class or peer group who immediately come to mind when you think about those who do, and do not, want to conform?

Several famous experiments in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s tested the tendency of individuals to conform to authority. Chapter 2 examined the Stanford Prison experiment. Within days of beginning the simulated prison experiment, the random sample of university students proved themselves capable of conforming to the roles of prison guards and prisoners to an extreme degree (Haney, Banks, and Zimbardo, 1973).

Stanley Milgram conducted experiments in the 1960s to determine how authority figures made individuals obedient (Milgram, 1963). This was shortly after the Adolf Eichmann war crime trial in which Eichmann claimed that he was just a bureaucrat following orders when he helped to organize the Holocaust.

Milgram asked experimental subjects to give (what they were thought) were electric shocks to others who answered questions incorrectly. Each time a wrong answer was given, the experimental subject was told to increase the intensity of the shock. The experiment was supposed to be testing the relationship between punishment and learning, but the person receiving the shocks was an actor, part of the experiment. As the experimental subjects increased the amount of voltage to “punish” wrong answers, the actor began to show distress, eventually begging the questioning to stop.

When the subjects became reluctant to administer more shocks, Milgram (wearing a white lab coat to underline his authority as a scientist) assured them that the shocked person would be OK. He would explain that the results of the experiment would be compromised if the subject did not continue the “punishments”. Seventy-one percent of the experimental subjects were willing to continue administering shocks, despite the actor crying out in pain, and a voltage dial labelled with warnings like “Danger: Severe shock.”

Making Connections: Sociological Research

Groupthink: Conforming to Expectations

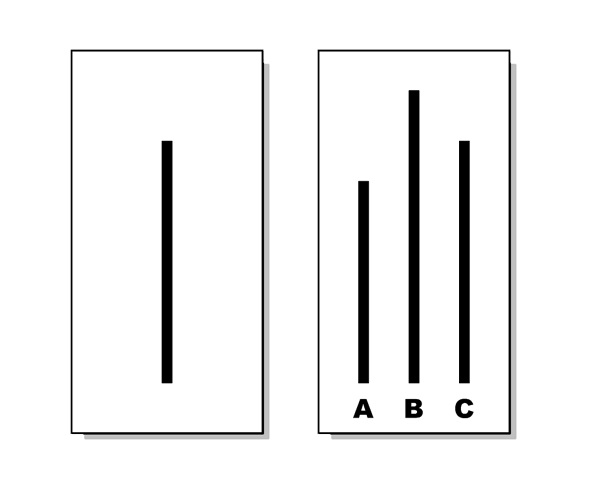

Psychologist Solomon Asch conducted experiments to show the strength of pressure to conform, specifically within a small group (1956). In 1951, he sat a small group of eight people around a table. Only one was the true experimental subject; the rest were actors or associates of the experimenter. However, the subject was led to believe that the others were all, like him, brought in for an experiment in visual judgment. The group was shown two cards: the first card with a single vertical line, and the second card with three vertical lines differing in length. The experimenter asked each participant, one at a time, which line on the second card matched up with the line on the first card.

However, this was not really a test of visual judgment. Rather, it was Asch’s study on the pressures of conformity. He was curious to see what the effect of multiple wrong answers would be on the subject, who presumably was able to tell which lines matched. To test this, Asch had each planted respondent answer in a specific way. The real subject could hear everyone else’s answers before it was his turn. The actor participants would often choose an answer that was clearly wrong.

Asch found that 37 out of 50 test subjects responded with an obviously incorrect answer at least once. Asch revised the study and repeated it. The subject still heard the staged wrong answers but was allowed to write down his answer rather than speak it aloud. In this version, the number of examples of conformity—giving an incorrect answer to not contradict the group— fell by two-thirds. He also found that group size had an impact on how much pressure the subject felt to conform.

The results showed that conforming to an incorrect answer was much more common when five or six people gave the incorrect answer than when only one other person gave an incorrect answer. Finally, Asch discovered that people were far more likely to give the correct answer in the face of near-unanimous consent if they had a single ally. If even one person in the group also dissented, the subject conformed only a quarter as often. Clearly, it was easier to be a minority of two than a minority of one.

Asch concluded that there are two main causes for conformity: people want to be liked by the group or they believe the group is better informed than they are. He found his results disturbing. To him, they revealed that intelligent, well-educated people would, with very little coaxing, go along with an untruth. This phenomenon is known as groupthink, the tendency to conform to the attitudes and beliefs of the group despite individual misgivings. He believed this result highlighted real problems with the education system and values in our society (Asch, 1956).

5.2. Formal Organizations

Many complain that large and impersonal secondary organizations dominate society. These organization–such as schools, businesses, health care and government–are referred to as formal organizations A formal organization is a large secondary group deliberately organized to achieve goals efficiently.

Typically, formal organizations are bureaucracies. A bureaucracy refers to what Max Weber termed “an ideal type” of formal organization (1946). In sociology, “ideal” does not mean “best”; it refers to a general model that could be used to describe most examples. For example, if your instructor told the class to picture a car in their minds, most students would picture a car that shares a set of characteristics: four wheels, a windshield, and so on. Everyone’s car could be different, however. Some might picture a two-door sports car while others might picture an SUV. The general shared idea of a car is the ideal type. Bureaucracies are similar. While each bureaucracy has its own individual features, the way each is deliberately organized to achieve its goals shares certain characteristics.

Types of Formal Organizations

Bureaucracies

Bureaucracies are an ideal type of formal organization. This does not mean that they are ideal (“best”) in an ethical sense but that they are organized by idealized model, like the example of the car above. People often complain about bureaucracies. People see bureaucracies as slow, rule-bound, difficult to navigate, and unfriendly.

Pioneer sociologist Max Weber described bureaucracy as having

- a hierarchy of authority,

- a clear division of labour,

- explicit rules, and

- impersonality.

Hierarchy of authority: Bureaucracy places one individual in charge of another. For example, if you are an employee at Walmart, your shift manager assigns you tasks. Your shift manager answers to the store manager, who must answer to the regional manager, and so on in a chain of command up to the CEO, who must answer to the board members, who answer to the stockholders. There is a clear chain of authority to allow everyone to know to whom to answer and for whom to be responsible. This permits the organization to make and enforce decisions.

A clear division of labour: Within a bureaucracy, everyone has a specialized task. In a school, for example, sociology instructors teach sociology, but they do fix leaks in the roof. That is a clear and common-sense division of labour. But what about in a restaurant where food is backed up in the kitchen while a hostess stands nearby texting on her phone? Her job is to seat customers, not to deliver food. Is this a smart division of labour?

Explicit rules refer to the way in which rules are outlined, written down, and standardized. For example, student guidelines are contained in the student handbook. As technology changes, organizations scramble to ensure their explicit rules cover emerging topics like cyberbullying and identity theft.

Impersonality of bureaucracies removes personal feelings from professional situations. Each position exists independently of who has the job so that clients and workers theoretically receive equal treatment. This was an attempt to eliminate favoritism. Through impersonality, large formal organizations try to protect their members, customers and clients. However, impersonality often results in disregard for personal experience. For example, you may be late for work because your car broke down, but the manager at Pizza Hut doesn’t care why you are late, only that you are late.

Finally, bureaucracies are, in theory, meritocracies, meaning that hiring and promotion are based on documented skills, rather than on favoritism or random choice. To get into college programs, you need to have good grade. To become a lawyer, you must graduate from law school and pass the provincial bar exam. Of course, there is a popular image of bureaucracies rewarding conformity and flattery rather than skill or merit. How well do you think established meritocracies identify talent?

There are several positive aspects of bureaucracies. Bureaucracies can improve efficiency, ensure equal opportunities, and increase efficiency. There are times when rigid hierarchies are needed. However, there can be inefficiency in the organization of bureaucracies. First, in some bureaucracies, workers can’t find meaning in the repetitive, standardized nature of their tasks. Second, bureaucracies can lead to inefficiency and ritualism (red tape). They can focus on rules and regulations to the point of undermining the organization’s goals and purpose. Third, bureaucracies tend toward inertia. You may have heard the expression “trying to turn a tanker around mid-ocean,” which refers to the difficulties of changing direction of something large and set in its ways. Inertia means bureaucracies focus on perpetuating themselves rather than effectively accomplishing the tasks they were designed to achieve. Finally, as Robert Michels (1911/1949) suggested, bureaucracies are characterized by the iron law of oligarchy in which the organization is ruled by a few elites. The organization promotes the self-interest of oligarchs and insulates them from the needs of the public.

Many bureaucracies grew large at the time that our school model was developed, during the Industrial Revolution. Young workers were trained, and organizations were built for mass production and assembly-line work in factories. A clear chain of command was useful. Now, in the information age, this kind of rigid training and organizations can decrease productivity and efficiency. Today’s workplace requires a faster pace, more problem solving, and a flexible approach to work. Smaller organizations are often more innovative and competitive because they have flatter hierarchies and more democratic decision making, which invites more communication, greater networking, and increased individual participation of members. Too many rules and a strict division of labour can leave an organization behind. Unfortunately, once established, bureaucracies can take on

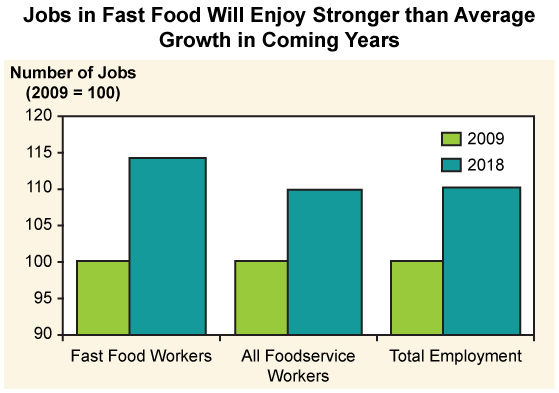

The McDonaldization of Society

The McDonaldization of society (Ritzer, 1994) refers to the increasing presence of the fast-food business model. This business model includes efficiency (the division of labour), predictability, calculability, and control (monitoring). For example, in your average chain grocery store, people at the cash register check out customers while stockers keep the shelves full of goods, and deli workers slice meat (efficiency). Whenever you enter a store in that grocery chain, you receive the same type of goods, see the same store organization, and find the same brands at the same prices (predictability). You can weigh your fruit and vegetable purchases rather than simply guessing at the price for that bag of onions, while the employees use a time card (calculability). Store employees wear uniforms and name tags) so that they can be easily identified. Security cameras monitor the store, and some parts of the store, such as the stockroom, are considered off-limits to customers (control).

While McDonaldization has resulted in improved profits and an increased availability of goods and services, it has also reduced the variety of goods. In addition, available products may be uniform, generic, and bland. Think of the difference between a mass-produced shoe and one made by a local shoemaker, between a chicken from a family-owned farm versus a corporate grower, or a cup of coffee from the local roaster instead of a coffee-shop chain. Ritzer also notes that the rational systems, as efficient as they are, are irrational because they become more important than the people working within them, or the clients being served. “Most specifically, irrationality means that rational systems are unreasonable systems. By that I mean that they deny the basic humanity, the human reason, of the people who work within or are served by them.” (Ritzer, 1994)

Making Connections: Sociological Research

Secrets of the McJob

We often talk about bureaucracies disparagingly, and no organizations have taken more heat than fast-food restaurants. The book and movie Fast Food Nation: The Dark Side of the All-American Meal by Eric Schossler (2001) paints an ugly picture of what goes in, what goes on, and what comes out of fast-food chains. From their environmental impact to their role in the U.S. obesity epidemic, fast-food chains are connected to numerous societal ills. Furthermore, working at a fast-food restaurant is often disparaged, and even referred to dismissively, as a McJob rather than a real job.

But business school professor Jerry Newman (2007) went undercover and worked behind the counter at seven fast-food restaurants to discover what really goes on there. His book, My Secret Life on the McJob, documents his experience. Newman found, unlike Schossler, that these restaurants have much good alongside the bad. Specifically, he asserted that the employees were honest and hard-working, the management was often impressive, and the jobs required a lot more skill and effort than most people imagined. In the book, Newman cites a pharmaceutical executive who states that a fast-food service job on an applicant’s résumé is a plus because it indicates the employee is reliable and can handle pressure.

So what do you think? Are these McJobs and the organizations that offer them still serving a role in the economy and people’s careers? Or are they dead-end jobs that typify all that is negative about large bureaucracies? Have you ever worked in one? Would you?

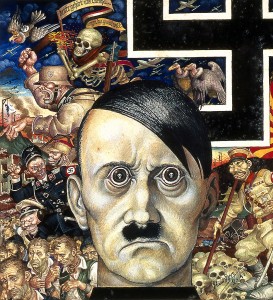

The Holocaust: What can sociology tell us?

In sociology, the group is always more than the sum of its parts. Individuals change their behaviour around others. Chapter 1 looked at how being in a crowd affected people very differently during the 2010 Vancouver Olympics and the riots of the 2011 Stanley Cup final. This chapter shows how being a member of a social group influences people to conform or attach to an in-group or out-group. How does the insight that “the group is more than the sum of the parts” help us understand the Holocaust?

The Holocaust (literally “whole burnt”) refers to the systematic extermination of European Jews and Roma by Nazis between 1941 and 1945. During this period, at least six million Jews and Roma were killed by the Nazis. How was it possible? It’s difficult to imagine that this event could merely be the product of isolated individuals. It needs to be understood at the level of group behaviour.

Clearly, some Germans in the 1930s were anti-Semitic, but even among these individuals the concept of Hitler’s Final Solution would have been unthinkable. Often, the explanation has been that the Nazi era in 20th century Germany was a temporary abnormality, a period of mass irrationality and social breakdown; an imposition of racism, hatred, and violence on the population by a power-hungry madman, Adolf Hitler, devoted to world domination. This explanation has some truth: the combination of war reparations imposed on Germany after the First World War and global capitalist crisis in the 1930s (the Great Depression) created conditions of instability and widespread desperation. Desperate people do not think clearly.

However, the sociological analysis of the rise of the Nazis and the implementation of the Holocaust is more discomforting. The Nazis were democratically elected not once but twice (in 1932 and 1933); the suspension of the constitution and the institution of emergency rule happened through legal, constitutional means; ordinary citizens enables the imposition of totalitarian rule and the internment of Jews, Roma, homosexuals, the disabled, and political opponents. And all of this was accomplished in one of the most modern, cultured, technologically advanced and rational societies in Europe. The leaders were not all sadists, criminals, or madmen. While there were clearly a few individuals in the camps known for their sadistic cruelty, “by conventional clinical criteria no more than 10 per cent of the SS could be considered ‘abnormal’” (Kren and Rappoport, quoted in Bauman, 1989).

As Zygmunt Bauman (1989) has argued, the Holocaust could not have occurred without the existence of modern, rational forms of social organization.

Bauman argues that it was the rational, efficient organization of the Nazi bureaucracy that enabled a series of solutions to be examined and rejected before the Final Solution was accepted. Bureaucracy also provided the three conditions which made it possible to overcome individual moral aversion to the mass killing:

- First, the violence was authorized according with bureaucratic procedures and hierarchical channels of command.

- Second, the violence was routinized by the rule-bound practices and clear division of labour of bureaucratic organization.

- Third, the victims of the violence were dehumanized through, not only ideological propaganda and media spin, but also the impersonality inherent in bureaucracy (Bauman, 1989).

The Holocaust was the product of the same ordinary sociological phenomena that operates in society today, including the formation of in-groups and out-groups, conformity to structures of authority, groupthink, and the ‘rational’ structure of bureaucracy. Therefore, an answer to how the Holocaust was possible must begin with studying collective behaviour. Why do individuals conform to the will of groups even when this means overcoming strong personal moral convictions or rational thinking? We need to examine the properties of groups to understand how the effect of the whole is more than the sum of the individual parts.

Chapter Summary

Groups largely define how we think of ourselves. There are two main types of groups: primary and secondary. A primary group is long-term with complex relationships.

The size and dynamics of a group greatly affects how members act. Primary groups rarely have formal leaders, although there can be informal leadership.

In secondary groups, there are two types of leadership functions, with expressive leaders focused on emotional health and wellness, and instrumental leaders more focused on results. Further, there are different leadership styles: democratic leaders, authoritarian leaders, and laissez-faire leaders. People use groups as standards of comparison to define themselves—as both who they are and who they are not. Sometimes groups can be used to exclude people or as a tool that strengthens prejudice.

Within a group, conformity is the extent to which people want to go along with group norms. Several experiments have illustrated how strong the drive to conform can be. Conformity and obedience can lead people to ethically and morally suspect acts.

Key Terms

authoritarian leader: A leader who issues orders and assigns tasks.

bureaucracy: A formal organization characterized by a hierarchy of authority, a clear division of labour, explicit rules, and impersonality.

category: People who share similar characteristics but who are not connected in any way.

clear division of labour: The structuring of work in a bureaucracy such that everyone has a specialized task to perform.

conformity: The extent to which an individual complies with group or societal norms.

crowd: A collection of people who exist in the same place at the same time, but who don’t interact or share a sense of identity.

democratic leader: A leader who encourages group participation and consensus-building before acting.

expressive function: A group function that serves an emotional need.

expressive leader: A leader who is concerned with process and with ensuring everyone’s emotional well- being.

formal organizations: Large, impersonal organizations.

glass ceiling: An invisible barrier that prevents women from achieving positions of leadership.

group: Refers to any collection of at least two people who interact with some frequency and who share a sense that their identity is somehow aligned with the group.

groupthink: The tendency to conform to the attitudes and beliefs of the group despite individual misgivings.

hierarchy of authority: A clear chain of command found in a bureaucracy.

in-group: A group a person belongs to and feels is an integral part of his or her identity.

instrumental function: Orientation toward a task or goal.

instrumental leader: A leader who is goal oriented with a primary focus on accomplishing tasks.

laissez-faire leader: A hands-off leader who allows members of the group to make their own decisions.

leadership function: The main focus or goal of a leader.

leadership style: The style a leader uses to achieve goals or elicit action from group members.

McDonaldization: The increasing presence of the fast-food business model in common social institutions.

meritocracy: A bureaucracy where membership and advancement are based on merit as shown through proven and documented skills.

out-group: A group that an individual is not a member of and may compete with.

primary groups: Small, informal groups of people who are closest to us.

reference groups: Groups to which an individual compares herself or himself.

secondary groups: Larger and more impersonal groups that are task-focused and time-limited.

social network: A collection of people tied together by a specific configuration of connections.

total institution: An organization in which participants live a controlled life and in which total resocialization occurs.

utilitarian organization: An organization that people join to fill a specific material need.

Chapter Quiz

- What role do secondary groups play in society?

- They are transactional, task-based, and short-term, filling practical needs.

- They provide a social network that allows people to compare themselves to others.

- The members give and receive emotional support.

- They allow individuals to challenge their beliefs and prejudices.

- When a high school student gets teased by her basketball team for receiving an academic award, she is dealing with competing ______________.

- Primary groups

- Out-groups

- Reference groups

- Secondary groups

- Which of the following is NOT an example of an in-group?

- The Ku Klux Klan

- A university club

- A synagogue

- A high school

- What is a group whose values, norms, and beliefs come to serve as a standard for one’s own behaviour?

- Secondary group

- Formal organization

- Reference group

- Primary group

- Who is more likely to be an expressive leader?

- The sales manager of a fast-growing cosmetics company

- A high school teacher at a youth correctional facility

- The director of a summer camp for chronically ill children

- A manager at a fast-food restaurant

- Which of the following is NOT an appropriate group for democratic leadership?

- A fire station

- A college classroom

- A high school prom committee

- A homeless shelter

- In Asch’s study on conformity, what contributed to the ability of subjects to resist conforming?

- A very small group of witnesses

- The presence of an ally

- The ability to keep one’s answer private

- All of the above

- Which of these is an example of a total institution?

- Jail

- High school

- Political party

- A gym

- What is an advantage of the McDonaldization of society?

- There is more variety of goods.

- There is less theft.

- There is more worldwide availability of goods.

- There is more opportunity for businesses.

- What is a disadvantage of the McDonaldization of society?

- There is less variety of goods.

- There is an increased need for employees with postgraduate degrees.

- There is less competition so prices are higher.

- There are fewer jobs so unemployment increases.

Short Answer

-

How has technology changed your primary groups and secondary groups? Do you have more or fewer primary groups due to online connectivity? Do you believe that someone, like Levy, can have a true primary group made up of people she has never met? Why or why not?

-

Compare and contrast two different political groups or organizations, such as the Occupy (Canada) and Tea Party movements (in the United States) or one of the Arab Spring uprisings. How do the groups differ in terms of leadership, membership, and activities? How do the group’s goals influence participants? Are any of them in-groups (and have they created out-groups)? Explain your answer.

-

The concept of hate crimes has been linked to in-groups and out-groups. Research and documents an example where people have been excluded or tormented due to this kind of group dynamic?

-

Where do you prefer to shop, eat out, or grab a cup of coffee? Large chains like Walmart or smaller retailers? Starbucks or a local restaurant? What do you base your decisions on? Does this section change how you think about these choices? Why or why not?

Further Research

Information about cyberbullying causes and statistics:

http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/85-002-x/2014001/article/ 14093- eng.htm#a7.

Take the What is your leadership style? quiz: http://psychology.about.com/qz/Whats-Your-Leadership-Style.

Explore other experiments on conformity: http://openstaxcollege.org/l/Stanford-Prison.

References

5. Introduction to Groups and Organizations

Boler, Megan. (2012, May 29). Occupy feminism: Start of a fourth wave? Rabble.ca. Retrieved February 25, 2014, from http://rabble.ca/news/2012/05/occupy-feminism-start-fourth-wave

Cabrel, Javier. (2011, November 28). NOFX – Occupy LA. LAWeekly.com. Retrieved February 10, 2012, from (http://blogs.laweekly.com/westcoastsound/2011/11/nofx_-_occupy_la_-_11-28-2011.php).

Bales, Robert F. (1970). Personality and Interpersonal Behavior. NY: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Bauman, Zygmunt. (2004). Identity. Cambridge UK: Polity

Christakis, N., & J. Fowler. (2009). Connected: The surprising power of our social networks and how they change our lives. New York: Little Brown and Co.

Cooley, Charles Horton. (1963). Social organizations: A study of the larger mind. New York: Shocken. (original published 1909)

Cyberbullying Research Center. (n.d.) Retrieved November 30, 2011, from (http://www.cyberbullying.us).

Hinduja, Sameer and Justin W. Patchin. (2010). Bullying, cyberbullying, and suicide. Archives of Suicide Research, 14(3): 206–221.

Marsden, Peter. (1987). Core discussion networks of Americans. American Sociological Review, 52:122-131.

New York Times. (2011). Times Topics: Occupy Wall Street. Retrieved February 10, 2012 from (http://topics.nytimes.com/top/reference/timestopics/organizations/o/occupy_wall_street/index.html?scp=1-spot&sq=occupy wall street&st=cse).

Occupy Solidarity Network. (n.d.) About. Occupy Wall Street. Retrieved November 27, 2011, from (http://occupywallst.org/about/).

Perreault, Samuel. (2011, September 15). Self-reported internet victimization in Canada, 2009. [PDF] Juristat. Statistics Canada catalogue no. 85-002-X. Retrieved September 20, 2014, from http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/85-002-x/2011001/article/11530-eng.pdf

Simmel, Georg. (1971). The problem of sociology. In D. Levine (Ed.), Georg Simmel: On individuality and social forms (pp. 23–27). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. (Original work published 1908)

Sumner, William. (1959). Folkways. New York: Dover. (original work published 1906)

Allemang, John. (2009, April 18). Elizabeth May is not only losing confidence — she agrees with Conrad Black. The Globe and Mail. Toronto, April 18: F.3.

Asch, Solomon. (1956). Studies of independence and conformity: A minority of one against a unanimous majority. Psychological Monographs, 70(9, Whole No. 416).

Boatwright, K.J. and L. Forrest. (2000). Leadership preferences: The influence of gender and needs for connection on workers’ ideal preferences for leadership behaviors. The Journal of Leadership Studies, 7(2): 18–34.

Carroll, William. (2010). The making of a transnational capitalist class: Corporate power in the 21st century. London: Zed Books.

Christakis, Nicholas and James Fowler. (2009). Connected: The surprising power of our social networks and how they shape our lives. NY: Little, Brown and Company

Headquarters, Department of the Army. (2006). Insurgencies and Countering Insurgencies. [PDF] Marine Corps Warfighting Publication. FM 3-24/MCWP 3-33.5, C1. Retrieved February 28, 2014, from http://www.fas.org/irp/doddir/army/fm3-24.pdf (publication has since been revised May 13, 2014)

Dowd, Maureen. (2008, January 9). Can Hillary cry her way back to the White House? New York Times. Retrieved February 10, 2012 (http://www.nytimes.com/2008/01/09/opinion/08dowd.html?pagewanted=all).

Foot, Richard. (2008, October 13). May changes debate rules. Edmonton journal, October 13: A.3.

Haney, C., W.C. Banks, and P.G. Zimbardo. (1973). Interpersonal dynamics in a simulated prison. International journal of criminology and penology, 1, 69–97.

McInturff, Kate. (2013). Closing Canada’s Gender Gap: Year 2240 Here We Come! [PDF] Canadian centre for policy Alternatives. Ottawa. Retrieved February 28, 2014, from http://www.policyalternatives.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/publications/National Office/2013/04/Closing_Canadas_Gender_Gap_0.pdf

Milgram, Stanley. (1963). Behavioral study of obedience. Journal of abnormal and social psychology, 67: 371–378.

Simmel, Georg. (1950). The isolated individual and the dyad. The sociology of Georg Simmel. Glencoe, IL: The Free Press. (original work published 1908)

Tannen, Deborah. (1994). You just don’t understand. NY: William Morrow and Co.

Weeks, Linton. (2011, June 9). The Feminine effect on politics. National public radio (NPR). Retrieved February 10, 2012, from (http://www.npr.org/2011/06/09/137056376/the-feminine-effect-on-presidential-politics).

Zuckerman, Ethan. (2011, January 14). The first Twitter revolution? Foreign policy. Retrieved February 28, 2014, from http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2011/01/14/the_first_twitter_revolution

Bauman, Zygmunt. (1989). Modernity and the holocaust. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Etzioni, Amitai. (1975). A comparative analysis of complex organizations: On power, involvement, and their correlates. New York: Free Press.

Goffman, Erving. (1961). Asylums: Essays on the social situation of mental patients and other inmates. Chicago, IL: Aldine.

Michels, Robert. (1949). Political parties. Glencoe, IL: Free Press. (original work published 1911)

Newman, Jerry. (2007). My secret life on the McJob. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Ritzer, George. (1994). The McDonaldization of society. Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge.

Schlosser, Eric. (2001). Fast food nation: The dark side of the all-American meal. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.

United States Department of Labor. Bureau of labor statistics occupational outlook handbook, 2010–2011 Edition. Retrieved February 10, 2012, from (http://www.bls.gov/oco/ocos162.htm).

Weber, Max. (1946). Bureaucracy. In H.H. Gerth and C.W. Mills (Eds.) From Max Weber: Essays in sociology (pp. 196-244). NY: Oxford University Press. (original work published 1922)

Weber, Max. (1968). Economy and society: An outline of interpretative sociology. New York: Bedminster. (original work published 1922)

Image Attributions

Figure 5.1. Occupy Victoria (vii) by r.a. paterson (https://www.flickr.com/photos/bcpaterson/6248358546/) used under CC BY SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/)

Figure 5.2. Idle No More Ottawa (2013) by Michelle Caron

(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Idle_No_More_2013_b.jpg) used under CC BY SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/)

Figure 5.6. Elizabeth May on CBC Radio One by ItzaFineDay (https://www.flickr.com/photos/itzafineday/2636098278) used under CC BY 2.0 license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/)

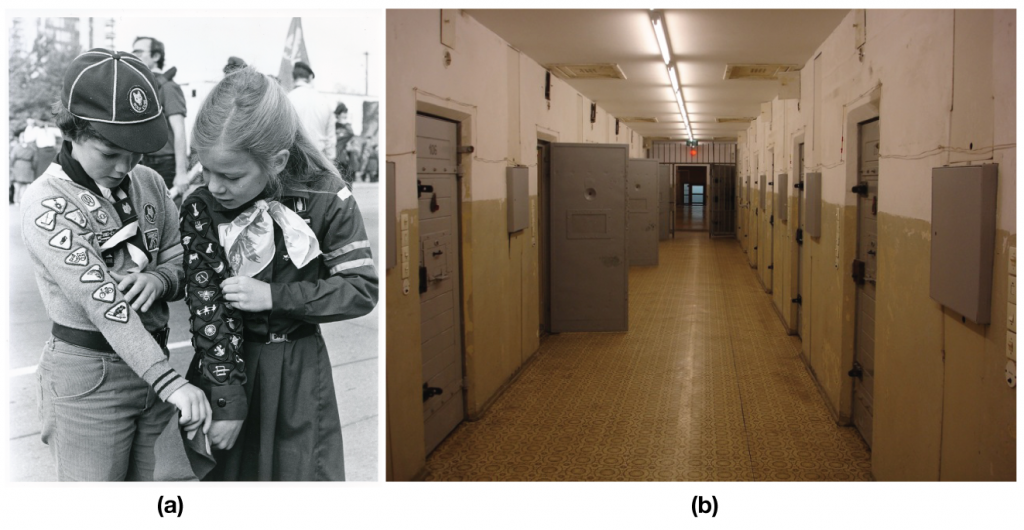

Figure 5.8. (a) Brownie and Cub compare badges by Girl Guides of Canada

(https://www.flickr.com/photos/girlguidesofcan/8488348265/in/photolist-dW61da) used under CC BY 2.0 license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/)

Long Descriptions

Figure 5.3: A graph with the x axis representing where a community exists (‘online’ or ‘in real life’) and the y axis representing the technology infrastructure (‘Do it yourself’ or ‘hosted’). The Z axis describes the state of tribe at outset (‘Scattered’ or ‘well formed’). Do it yourself online communities start out “scattered”. Hosted communities in real life start out “well formed.” [Return to Figure 5.3].

Solutions to Chapter Quiz

1 a, | 2 c, | 3 d, | 4 c, | 5 c, | 6 a, | 7 d, | 8 a, | 9 b, | 10 c, | 11 a

[Return to quiz]