12 Work in Canada

Learning Objectives

12.1. Introduction to Work and the Economy

- Understand what economy refers to.

- Describe the current Canadian workforce and the trend of polarization.

- Explain how women and immigrants have impacted the modern Canadian workforce.

- Understand the basic elements of poverty in Canada today.

12.1. Introduction to Work and the Economy

Ever since the first people traded one item for another, there has been some form of economy in the world. The economy is how people meet their wants and needs though producing and exchanging goods and services. In sociology, economy refers to the social institutions through which a society’s resources (goods and services) are managed.

Goods are the physical objects we find, grow, or make in order to meet human needs. Goods can meet essential needs, such as shelter, clothing, and food, or they can be luxuries — those things we do not need to live but want anyway. Goods produced for sale on the market are called commodities. In contrast to these objects, services are activities that benefit people. Examples of services include food preparation and delivery, health care, education, and entertainment. These services provide resources to maintain and improve a society. The food industry helps ensure that all of a society’s members have access to nutrition. Health care and education systems care for those in need, help foster longevity, and equip people to become productive members of society.

Economy is one of human society’s earliest social structures. Our earliest forms of writing (such as Sumerian clay tablets) were developed to record transactions, payments, and debts between merchants. As societies grow and change, so do their economies. The economy of a small farming community is very different from the economy of a large nation with advanced technology.

12.2. Work in Canada

Common wisdom states that if you study hard, develop good work habits, and graduate from high school or college, then you’ll get a good job. And although the reality has always been more complex than the myth, worldwide recessions and other economic changes make it harder to win the employment game.

The data are grim: for example, in the United States, from December 2007 through March 2010, 8.2 million workers lost their jobs, and the unemployment rate grew to almost 10% nationally, with some states showing much higher rates (Autor, 2010). Times are very challenging for those in the workforce in Canada too. For those finishing their schooling, often with enormous student-debt burdens, finding employment is not just challenging — it can be terrifying.

So where did all the jobs go? Will any of them be coming back? If not, what new ones will there be? How do you find and keep a good job now? These are the kinds of questions people are currently asking about the job market in Canada.

Polarization in the Workforce

The mix of jobs available in Canada has always varied. Geography, race, gender, and other factors have always played a role in finding employment. More recently, increased outsourcing (or contracting work to an outside source) of manufacturing jobs to developing nations has greatly diminished the number of high-paying, often unionized, blue-collar positions available. A similar problem exists in the white-collar sector, with many clerical and support positions also being outsourced. Think of the number of international technical-support call centres in Mumbai, India! The number of supervisory and managerial positions has been reduced as companies streamline their command structures. Industries continue to consolidate through mergers. Even highly educated skilled workers such as computer programmers have seen their jobs vanish overseas.

Automation (replacing workers with technology) of the workplace is another cause of the changes in the job market. Computers can be programmed to do many routine tasks faster and less expensively than people who used to do such tasks. Jobs like bookkeeping, clerical work, and repetitive tasks on production assembly lines all lend themselves to automation. Think about the newer automated toll passes we can install in our cars. Toll collectors are just one of the many endangered jobs that will soon cease to exist.

Despite all this, the job market is growing in some areas, but in a very polarized fashion. Polarization means that a gap has developed in the job market, with most employment opportunities at the lowest and highest levels and few jobs for those with mid- level skills and education. At one end, there is strong demand for low-skilled, low-paying jobs in industries like food service and retail. On the other end, some research shows that in certain fields there has been a steadily increasing demand for highly skilled and educated professionals, technologists, and managers. These high-skilled positions also tend to be highly paid (Autor, 2010).

The fact that some positions are highly paid while others are not is an example of the dual labour market structure, a division of the economy into sectors with different levels of pay. The primary labour market consists of high-paying jobs in the public sector, manufacturing, telecommunications, biotechnology, and other similar sectors that require high levels of capital investment (or other restrictions) that limit the number of businesses able to enter the sector. The costs of labour are considered marginal in comparison to the total capital investment required. Jobs in the sector usually offer good benefits, security, prospects for advancement, and comparatively higher levels of unionization.

The secondary labour market consists of jobs in more competitive sectors of the economy like service industries, restaurants, and commercial enterprises, where the cost of entry for businesses is relatively low. Jobs in the secondary labour market are usually poorly paid, offer few if any benefits, and have little job security, poor prospects for advancement, and minimal unionization. Wages paid to employees make up a significant portion of the cost of products or services offered to consumers, and because of the high level of competition, businesses are obliged to keep the cost of labour to a minimum to remain competitive.

Hard work does not guarantee success in the dual labour market economy, because social capital—the accumulation of a network of social relationships and knowledge that will provide a platform from which to achieve financial success—in the form of connections or higher education are often required to access the high-paying jobs. Increasingly, we are realizing intelligence and hard work are not enough. If you lack knowledge of how to leverage the right names, connections, and players, you are unlikely to experience upward mobility. Particularly in the knowledge economy, which generates a new dual labour market between jobs that require high levels of education (scientists, programmers, designers, etc.) and support jobs (secretarial, data entry, technicians, etc.), social capital in the form of formal education is a condition for accessing quality jobs.

The division between those who are able to access, create, use, and disseminate knowledge and those who cannot is often referred to as the knowledge divide. With so many jobs being outsourced or eliminated by automation, what kinds of jobs are available in Canada?

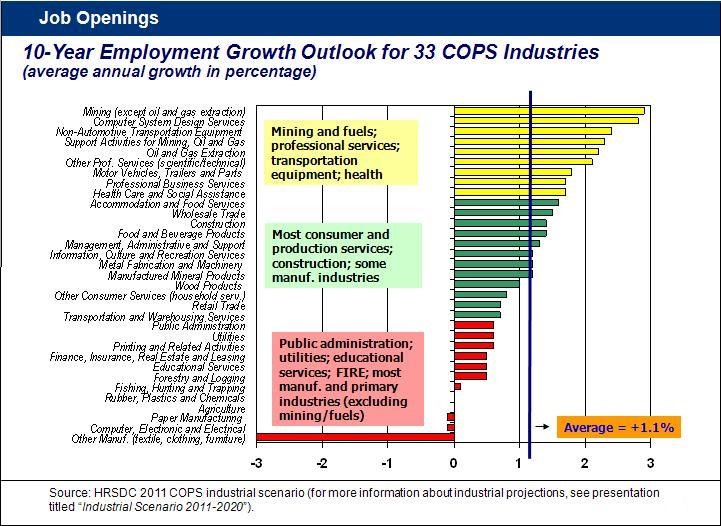

While manufacturing jobs are in decline and fishing and agriculture are static, several job markets are expanding. These include resource extraction, computer and information services, professional business services, health care and social assistance, and accommodation and food services. Figure 12.2, from Employment and Social Development Canada, illustrates areas of projected growth.

Professional and related jobs, which include any number of positions, typically require significant education and training and tend to be lucrative career choices. Service jobs, according to Employment and Social Development Canada, can include everything from consumer service jobs such as scooping ice cream, to producer service jobs that contract out administrative or technical support, to government service jobs including teachers and bureaucrats (Labour Market Research and Forecasting Policy Research Directorate, 2011b).

There is a wide variety of training needed, and therefore an equally large wage discrepancy. One of the largest areas of growth by industry, rather than by occupational group (as seen above), is in the health field (Labour Market Research and Forecasting Policy Research Directorate, 2011a). This growth is across occupations, from practical nurses and assistants to management-level staff. Baby boomers are living longer than any generation before, and the growth of this population segment requires an increase in our country’s elder care system, from home health care nursing to geriatric nutrition.

Notably, jobs in manufacturing are in decline. This is an area where those with less education traditionally could find steady, if low-wage, work. With these jobs disappearing, more and more workers will find themselves untrained for available employment. Another projected trend in employment relates to the level of education and training required to gain and keep a job.

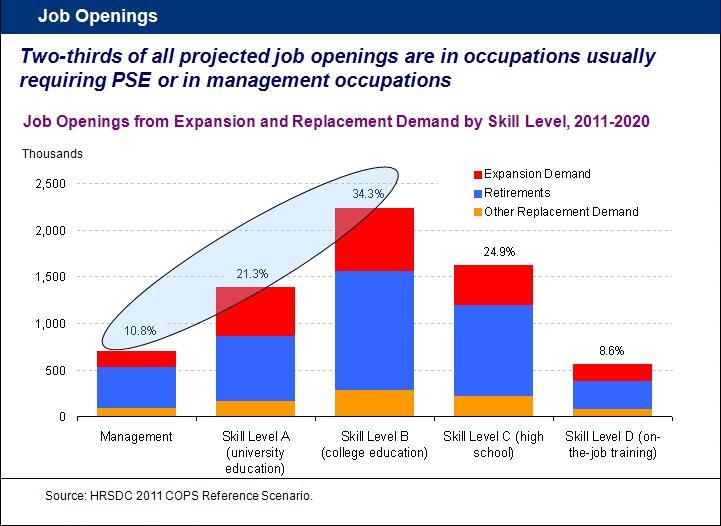

As Figure 12.3 shows, growth rates are higher for those with more education. It is estimated that between 2011 and 2020, there will be 6.5 million new job openings due to economic growth or retirement, two-thirds of which will be in occupations that require post-secondary education (“PSE” in the chart) or in management positions (Labour Market Research and Forecasting Policy Research Directorate, 2011a). 70% of new jobs created through economic growth are projected to be in management or occupations that require post-secondary education. Those with a university degree may expect job growth of 21.3%, and those with a college degree or apprenticeship 34.3%.

At the other end of the spectrum, jobs that require a high school diploma or equivalent are projected to grow at only 24.9%, while jobs that require less than a high school diploma will grow at 8.6%. Quite simply, without a degree, it will be more difficult to find a job. These projections are based on overall growth across all occupation categories, so obviously there will be variations within different occupational areas. Seven out of the ten occupations with the highest proportion of job openings are in management and the health sector. However, once again, those who are the least educated will be the ones least able to fulfill the Canadian dream.

Women in the Workforce

In the past, rising education levels in Canada were able to keep pace with the rise in the number of education-dependent jobs. Since the late 1970s, men have been enrolling in university at a lower rate than women, and graduating at a rate of almost 10% less (Wang and Parker, 2011). In 2008, 62% of undergraduate degrees and 54% of graduate degrees were granted to women (Drolet, 2011). The lack of male candidates reaching the education levels needed for skilled positions has opened opportunities for women and immigrants. Women have been entering the workforce in ever-increasing numbers for several decades. Their increasingly higher levels of education attainment than men has resulted in many women being better positioned to obtain high-paying, high-skill jobs. Between 1991 and 2011, the percentage of employed women between the ages of 25 and 34 with a university degree increased from 19% to 40%, whereas among employed men aged 25 to 34 the percentage increased from 17% to 27%.

It is interesting to note however that at least 20% of all women with a university degree were still employed in the same three occupations as they were in 1991: registered nurses, elementary school and kindergarten teachers, and secondary school teachers. The top three occupations for university-educated men (11% of this group) were computer programmers and interactive media developers, financial auditors and accountants, and secondary school teachers (Uppal and LaRochelle-Côté, 2014). While women are getting more and better jobs and their wages are rising more quickly than men’s wages are, Statistics Canada data show that they are still earning only 76% of what men are for the same positions. However when the wages of young women aged 25 to 29 are compared to young men in the same age cohort, the women now earn 90% of young men’s hourly wage (Statistics Canada, 2011).

Immigration and the Workforce

Simply put, people will move from where there are few or no jobs to places where there are jobs, unless something prevents them from doing so. The process of moving to a country is called immigration. Canada has long been a destination for workers of all skill levels. While the rate decreased somewhat during the economic slowdown of 2008, immigrants, both legal and illegal, continue to be a major part of the Canadian workforce. In 2006, before the recession arrived, immigrants made up 19.9% of the workforce, up from 19 percent in 1996 (Kustec, 2012). The economic downturn affected them disproportionately. In 2008, employment rates were at the peak for both native-born Canadians (84.1%) and immigrants (77.4%). In 2009, these figures dropped to 82.2% and 74.9% respectively, meaning that the gap in employment rates increased to 7.3 percentage points from 6.7. The gap was greater between native-born and very recent immigrants (18.6 percentage points in 2009, compared with a gap of 17.5 points in 2008) (Yssaad, 2012). Interestingly, in the United States, this trend was reversed. The unemployment rate decreased for immigrant workers and increased for native workers (Kochhar, 2010). This no doubt did not help to reduce tensions in that country about levels of immigration, particularly illegal immigration.

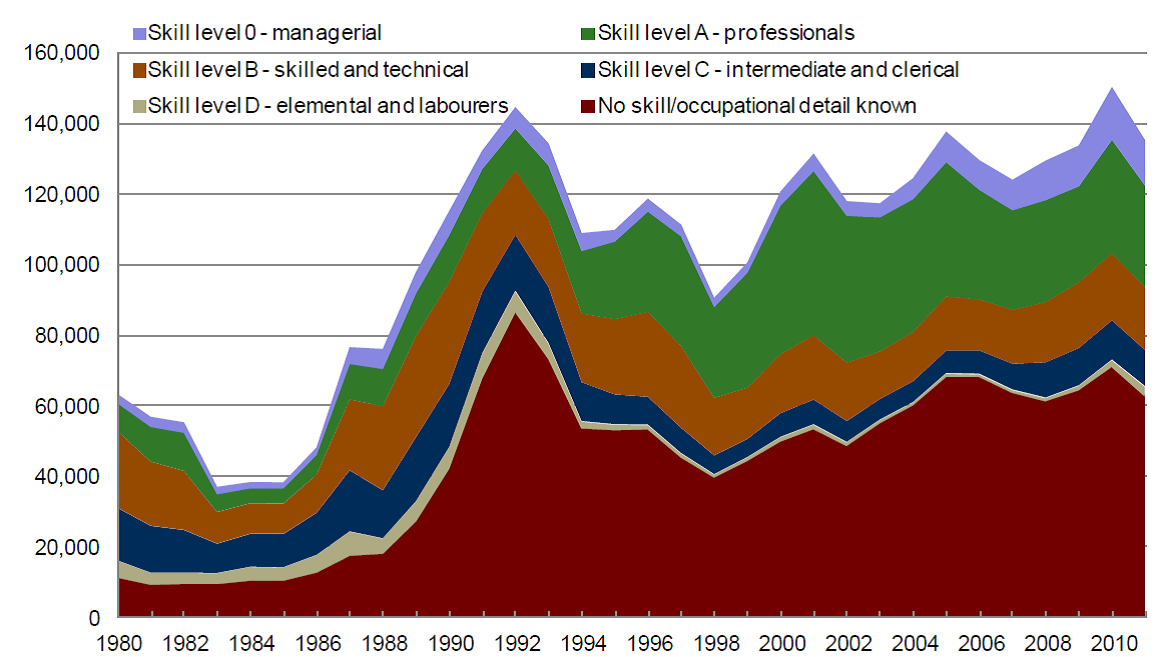

Recent political debate about the Temporary Foreign Worker Program has been fuelled by conversations about low-skilled service industry jobs being taken by low-earning foreign workers (Mas, 2014). It should be emphasized that a substantial portion of working-age immigrants (i.e., not temporary workers) landing in Canada are highly educated and highly skilled (Figure 12.4). They play a significant role in filling skilled positions that open up through both job creation and retirement. About half of the landed immigrants identify an occupational skill, 80 to 90% of which fall within the higher skill level classifications. Of the other 50% of landed immigrants who intend to work but do not indicate a specific occupational skill, most have recently completed school and are new to the labour market, or have landed under the family class or as refugees — classes which are not coded by occupation (Kustec, 2012).

Poverty in Canada

When people lose their jobs during a recession or in a changing job market, it takes longer to find a new one, if they can find one at all. If they do, it is often at a much lower wage or not full time. This can force people into poverty. In Canada, we tend to have what is called relative poverty, defined as being unable to live the lifestyle of the average person in your country. This must be contrasted with the absolute poverty that can be found in underdeveloped countries, defined as being barely able, or unable, to afford basic necessities such as food (Byrns, 2011). We cannot even rely on unemployment statistics to provide a clear picture of total unemployment in Canada. First, unemployment statistics do not take into account underemployment, a state in which people accept lower-paying, lower-status jobs than their education and experience qualifies them to perform. Second, unemployment statistics only count those:

- who are actively looking for work

- who have not earned income from a job in the past four weeks

- who are ready, willing, and able to work

The unemployment statistics provided by Statistics Canada are rarely accurate, because many of the unemployed become discouraged and stop looking for work. Not only that, but these statistics undercount the youngest and oldest workers, the chronically unemployed (e.g., homeless), and seasonal and migrant workers.

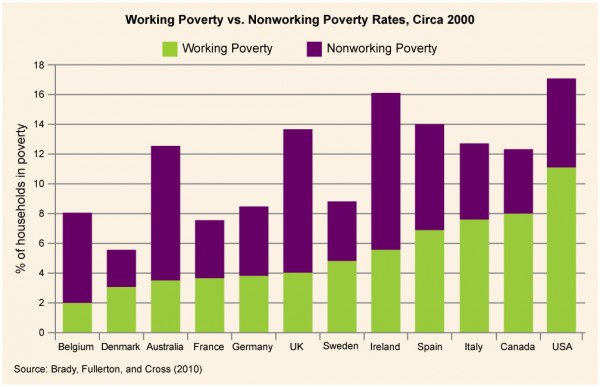

A certain amount of unemployment is a direct result of the relative inflexibility of the labour market, considered structural unemployment, which describes when there is a societal level of disjuncture between people seeking jobs and the available jobs. This mismatch can be geographic (they are hiring in Alberta, but the highest rates of unemployment are in Newfoundland and Labrador), technological (skilled workers are replaced by machines, as in the auto industry), or can result from any sudden change in the types of jobs people are seeking versus the types of companies that are hiring. Because of the high standard of living in Canada, many people are working at full-time jobs but are still poor by the standards of relative poverty. They are the working poor. Canada has a higher percentage of working poor than many other developed countries (Brady, Fullerton, and Cross, 2010). In terms of employment, Statistics Canada defines the working poor as those who worked for pay at least for at least 910 hours during the year, and yet remain below the poverty line according to the Market Basket Measure (i.e., they lack the disposable income to purchase a specified “basket” of basic goods and services). Many of the facts about the working poor are as expected: those who work only part time are more likely to be classified as working poor than those with full-time employment; higher levels of education lead to less likelihood of being among the working poor; and those with children under 18 are four times more likely than those without children to fall into this category. In 2011, 6.4% of Canadians of all ages lived in households classified as working poor (Employment and Social Development Canada, 2011).

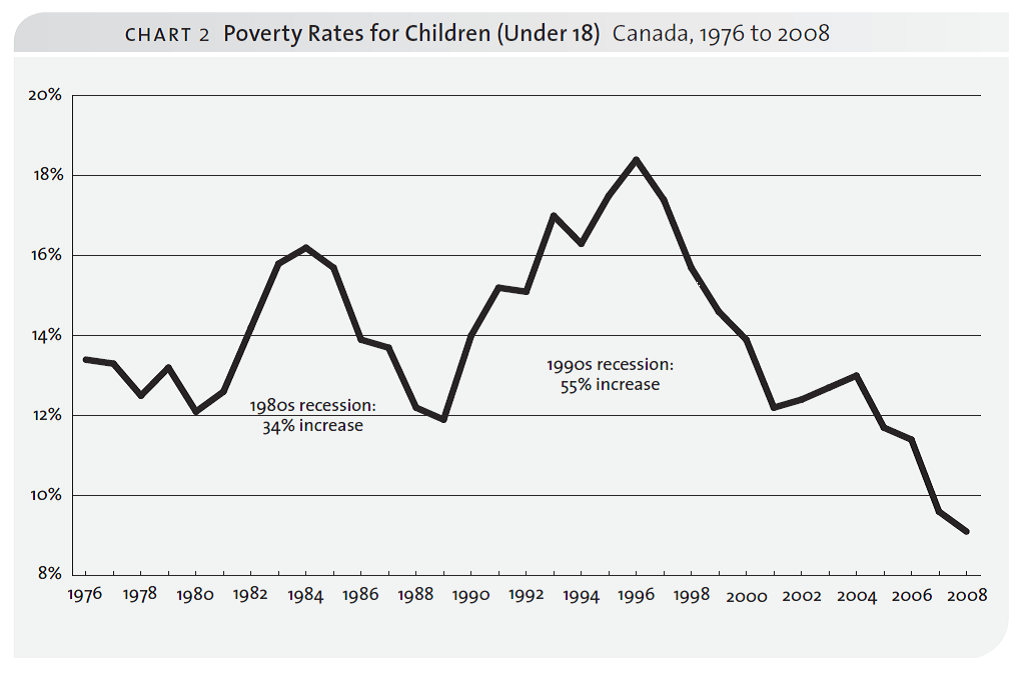

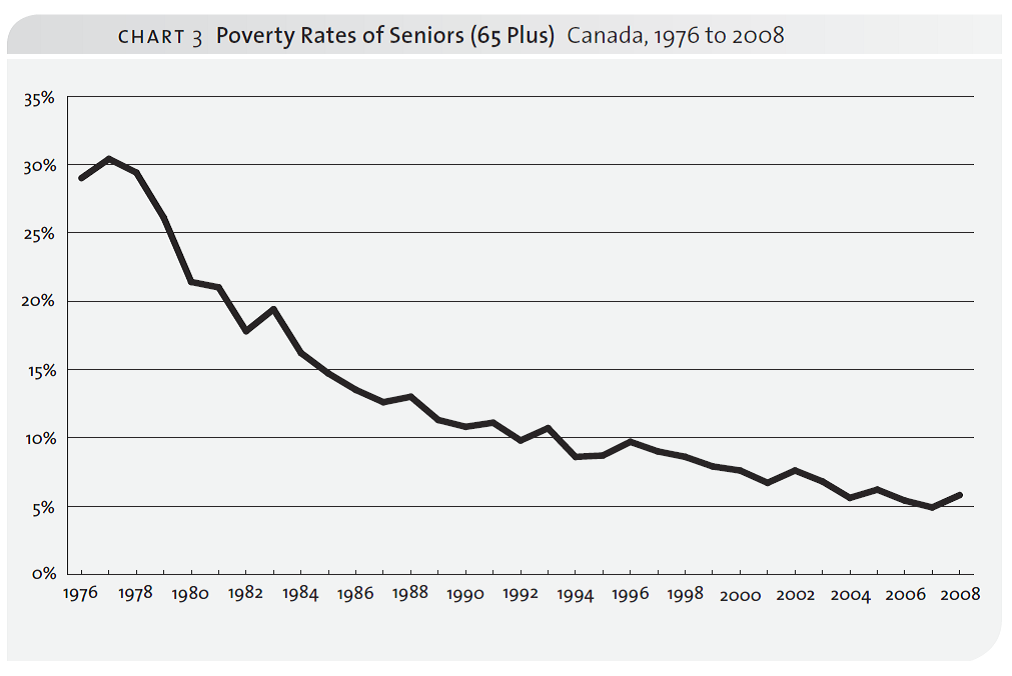

Most developed countries such as Canada protect their citizens from absolute poverty by providing different levels of social services such as employment insurance, welfare, health care, and so on. They may also provide job training and retraining so that people can re-enter the job market. In the past, the elderly were particularly vulnerable to falling into poverty after they stopped working; however, the Canada and Quebec Pension Plans, the Old Age Security program, and the Guaranteed Income Supplement are credited with successfully reducing old age poverty. A major concern in Canada is the number of young people growing up in poverty, although these numbers have been declining as well. About 606,000 children younger than 18 lived in low-income families in 2008. The proportion of children in low-income families was 9% in 2008, half the 1996 peak of 18% (Statistics Canada, 2011). Growing up poor can cut off access to the education and services people need to move out of poverty and into stable employment. As we saw, more education was often a key to stability, and those raised in poverty are the ones least able to find well-paying work, perpetuating a cycle.

With the shift to neoliberal economic policies, there has been greater debate about how much support local, provincial, and federal governments should give to help the unemployed and underemployed. Often the issue is presented as one in which the interests of “taxpayers” are opposed to the “welfare state.” It is interesting to note that in social democratic countries like Norway, Finland, and Sweden, there is much greater acceptance of higher tax rates when these are used to provide universal health care, education, child care, and other forms of social support than there is in Canada. Nevertheless, the decisions made on these issues have a profound effect on working in Canada.

Chapter Summary

Introduction to Work and the Economy

Economy refers to the social institution through which a society’s resources (goods and services) are managed. The Agricultural Revolution led to development of the first economies that were based on trading goods. Mechanization of the manufacturing process led to the Industrial Revolution and gave rise to two major competing economic systems. Under capitalism, private owners invest their capital and that of others to produce goods and services they can sell in an open market. Prices and wages are set by supply and demand and competition. Under socialism, the means of production is commonly owned, and the economy is controlled centrally by government. Several countries’ economies exhibit a mix of both systems. Convergence theory seeks to explain the correlation between a country’s level of development and changes in its economic structure.

Work in Canada

The job market in Canada is meant to be a meritocracy that creates social stratifications based on individual achievement. Economic forces, such as outsourcing and automation, are polarizing the workforce, with most job opportunities being either low-level, low-paying manual jobs or high-level, high-paying jobs based on abstract skills. Women’s role in the workforce has increased, although they have not yet achieved full equality. Immigrants play an important role in the Canadian labour market. The changing economy has forced more people into poverty even if they are working. Welfare, old age pensions, and other social programs exist to protect people from the worst effects of poverty.

Key Terms

automation: Workers being replaced by technology.

commodities: Goods produced for sale on the market.

dual labour market: The division of the economy into high-wage and low-wage sectors.

economy: The social institution through which a society’s resources (goods and services) are managed.

goods: The physical objects we find, grow, or make in order to meet our needs and the needs of others.

knowledge divide: The division between those who are able to access, create, utilize, and disseminate knowledge and those who cannot.

outsourcing: When jobs are contracted to an outside source, often in another country.

polarization: When the differences between low-end and high-end jobs becomes greater and the number of people in the middle levels decreases.

recession: When there are two or more consecutive quarters of economic decline.

services: Activities that benefit people, such as health care, education, and entertainment.

social capital: The accumulation of a network of social relationships and knowledge that will provide a platform from which to achieve financial success — in the form of connections or higher education.

structural unemployment: When there is a societal level of disjuncture between people seeking jobs and the jobs that are available.

underemployment: A state in which a person accepts a lower-paying, lower-status job than his or her education and experience qualifies him or her to perform.

working poor: Statistics Canada defines the working poor as those who worked for pay at least for at least 910 hours during the year, and yet remain below the poverty line according to the Market Basket Measure (they lack the disposable income to purchase a specified “basket” of basic goods and services).

Chapter Quiz

12.1. Introduction to Work and the Economy

- Which of these is an example of a commodity?

- Cooking

- Corn

- Teaching

- Writing

- When did the first economies begin to develop?

- When all of the hunter-gatherers died

- When money was invented

- When people began to grow crops and domesticate animals

- When the first cities were built

- What is the most important commodity in a postindustrial society?

- Electricity

- Money

- Information

- Computers

- In which sector of an economy would someone working as a software developer be?

- Primary

- Secondary

- Tertiary

- Quaternary

- Which is an economic policy based on national policies of accumulating silver and gold by controlling markets with colonies and other countries through taxes and customs charges?

- Capitalism

- Communism

- Mercantilism

- Mutualism

- Who was the leading theorist on the development of socialism?

- Karl Marx

- Alex Inkeles

- Émile Durkheim

- Adam Smith

- The type of socialism now carried on by Cuba is a form of ______ socialism.

- centrally planned

- market

- utopian

- zero-sum

- Which country serves as an example of convergence?

- Singapore

- North Korea

- England

- Canada

- Which is evidence that the Canadian workforce is largely a meritocracy?

- Job opportunities are increasing for highly skilled jobs.

- Job opportunities are decreasing for mid-level jobs.

- Highly skilled jobs pay better than low-skill jobs.

- Women tend to make less than men do for the same job.

- If someone does not earn enough money to pay for the essentials of life he or she is said to be _____ poor.

- absolutely

- essentially

- really

- working

- About what percentage of the workforce in Canada are legal immigrants?

- Less than 1%

- 1%

- 20%

- 66%

Short Answer

12.1. Introduction to Work and the Economy

-

Explain the difference between state socialism with central planning and market socialism.

-

In what ways can capitalistic and socialistic economies converge?

-

Describe the impact a rapidly growing economy can have on families.

-

How do you think the Canadian economy will change as we move closer to a technology-driven service economy?

-

As polarization occurs in the Canadian job market, this will affect other social institutions. For example, if mid-level education does not lead to employment, we could see polarization in educational levels as well. Use the sociological imagination to consider what social institutions may be impacted, and how.

-

Do you believe we have a true meritocracy in Canada? Why or why not?

Further Research

12.1. Introduction to Work and the Economy

Green jobs have the potential to improve not only your prospects of getting a good job, but the environment as well. Learn more about the green revolution in jobs: http://openstaxcollege.org/l/greenjobs.

The role of women in the workplace is constantly changing: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/89-503-x/2010001/article/11387-eng.htm.

The Employment Projections Program of Employment and Social Development Canada looks at a ten-year projection for jobs and employment. See some employment trends for the next decade: http://occupations.esdc.gc.ca/sppc-cops/w.2lc.4m.2@-eng.jsp.

Global poverty is tracked by the globalissues.org website. See recent analyses and statistics about poverty: http://www.globalissues.org/article/26/poverty-facts-and-stats.

References

12.1. Introduction to Work and the Economy

Abramovitz, Moses. (1986). Catching up, forging ahead and falling behind. Journal of Economic History, 46(2):385–406. Retrieved February 6, 2012, from http://www.jstor.org/pss/2122171.

Antony, James. (1998). Exploring the factors that influence men and women to form medical career aspirations. Journal of College Student Development, 39:417–426.

Bond, Eric, Sheena Gingerich, Oliver Archer-Antonsen, Liam Purcell, and Elizabeth Macklem. (2003). The industrial revolution — Innovations. Retrieved February 6, 2012, from http://industrialrevolution.sea.ca/innovations.html.

Bookchin, Murray. (1982). The ecology of freedom: The emergence and dissolution of hierarchy. Palo Alto CA: Cheshire Books.

Boxall, Michael. (2006, February 9). Just don’t call it funny money. The Tyee. Retrieved July 25, 2014, from http://thetyee.ca/News/2006/02/09/FunnyMoney/

Davis, Kingsley and Wilbert Moore. (1945). Some principles of stratification. American Sociological Review, 10:242–249.

Diamond, J. and P. Bellwood. (2003, April 25). Farmers and their languages: The first expansions. Science, April 25: 597-603.

The Economist. (2011). Economics A-Z terms beginning with C: Catch-up Effect. The Economist.com. Retrieved February 5, 2012, from http://www.economist.com/economics-a-to-z/c#node-21529531.

Fidrmuc, Jan. (2002). Economic reform, democracy and growth during post-communist transition. [PDF] European Journal of Political Economy, 19(30):583–604. Retrieved February 6, 2012, from http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTDECINEQ/Resources/fidrmuc.pdf.

Goldsborough, Reid. (2010). A case for the world’s oldest coin: Lydian Lion. World’s Oldest Coin – First Coins [Website]. Retrieved February 6, 2012, from http://rg.ancients.info/lion/article.html).

Gregory, Paul R. and Robert C. Stuart. (2003). Comparing Economic Systems in the Twenty-First Century. Boston, MA: South-Western College Publishing.

Greisman, Harvey C. and George Ritzer. (1981). Max Weber, critical theory, and the administered world. Qualitative Sociology, 4(1):34–55. Retrieved February 6, 2012, from http://www.springerlink.com/content/k14085t403m33701/.

Horne, Charles F. (1915). The code of Hammurabi : Introduction. Yale University. Retrieved July 11, 2016, from http://avalon.law.yale.edu/subject_menus/hammenu.asp.

Kenessey, Zoltan. (1987). The primary, secondary, tertiary and quaternary sectors of the economy. The Review of Income and Wealth, 33(4):359–386.

Kerr, Clark, John T. Dunlap, Frederick H. Harbison, and Charles A. Myers. (1960). Industrialism and industrial man. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Kohn, Melvin, Atsushi Naoi, Carrie Schoenbach, Carmi Schooler, and Kazimierz Slomczynski. (1990). Position in the class structure and psychological functioning in the United States, Japan, and Poland. American Journal of Sociology, 95:964–1008.

Macdonald, David. (2014, April). Outrageous fortune: Documenting Canada’s wealth gap. [PDF] Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. Retrieved July 25, 2014, from https://www.policyalternatives.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/publications/National%20Office/2014/04/Outrageous_Fortune.pdf.

Maddison, Angus. (2003). The world economy: Historical statistics. Paris: Development Centre, OECD. Retrieved February 6, 2012, from http://www.theworldeconomy.org/.

Marx, Karl and Friedrich Engels. (1998). The communist manifesto. New York: Penguin. (Original work published 1848)

Marx, Karl and Friedrich Engels. (1988). Economic and philosophic manuscripts of 1844 and the communist manifesto. (Translated by M. Milligan). New York: Prometheus Books. (Original work published 1844)

Mauss, Marcel. (1990). The gift: The form and reason for exchange in archaic societies, London: Routledge. (Original work published 1922)

Merton, Robert. (1968). Social theory and social structure. New York: Free Press.

Proudhon, Pierre-Joseph. (2010). Property is theft! A Pierre-Joseph Proudhon anthology. Iain McKay (Ed.). Retrieved February 15, 2012, from http://anarchism.pageabode.com/pjproudhon/property-is-theft. (Original work published 1840)

Schwermer, Heidemarie. (2007). Gib und Nimm. Retrieved January 22, 2012, from http://www.heidemarieschwermer.com/.

Schwermer, Heidemarie. (2011). Living without money. Retrieved January 22, 2012, from http://www.livingwithoutmoney.org.

Sokoloff, Kenneth L. and Stanley L. Engerman. (2000). History lessons: Institutions, factor endowments, and paths of development in the New World. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 14(3)3:217–232.

Statistics Canada. (2012, November). Canada year book 2012. Statistics Canada [PDF] Catalogue no. 11-402-XPE. Retrieved July 25, 2012, from http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/11-402-x/2012000/pdf-eng.htm.

Sunyal, Ayda, Onur Sunyal and Fatma Yasin. (2011). A comparison of workers employed in hazardous jobs in terms of job satisfaction, perceived job risk and stress: Turkish jean sandblasting workers, dock workers, factory workers and miners. Social Indicators Research, 102:265–273.

Wheaton, Sarah. (2011, September 15). Perry repeats socialist charge against Obama policies. New York Times. Retrieved January 30, 2012 from http://thecaucus.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/09/15/perry-repeats-socialist-charge-against-obama-policies.

Autor, David. (2010, April). The polarization of job opportunities in the U.S. labor market implications for employment and earnings. MIT Department of Economics and National Bureau of Economic Research. Retrieved February 15, 2012, from http://econ-www.mit.edu/files/5554.

Brady, David, Andrew Fullerton, and Jennifer Moren Cross. (2010). More than just nickels and dimes: A cross-national analysis of working poverty in affluent democracies. [PDF] Social Problems, 57:559–585. Retrieved July 12, 2016, from https://www.wzb.eu/sites/default/files/u31/bradyetal2010.pdf.

Drolet, Marie. (2011). Why has the gender wage gap narrowed? [PDF] Ottawa: Statistics Canada. Retrieved July 25, 2014, from http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/75-001-x/2011001/pdf/11394-eng.pdf.

Employment and Social Development Canada. (2011). Financial security – Low income incidence. Indicators of well-being in Canada. Ottawa: Employment and Social Development Canada. Retrieved July 25, 2014, from http://www4.hrsdc.gc.ca/.3ndic.1t.4r@-eng.jsp?iid=23#M_8.

Holland, Laurence H.M. and David M. Ewalt. (2006, August 7). Making real money in virtual worlds. Forbes. Retrieved January 30, 2012, from http://www.forbes.com/2006/08/07/virtual-world-jobs_cx_de_0807virtualjobs.html.

Kochhar, Rokesh. (2010, October 29). After the great recession: Foreign born gain jobs; Native born lose jobs. Pew Hispanic Center. Retrieved January 29, 2012, from http://pewresearch.org/pubs/1784/great-recession-foreign-born-gain-jobs-native-born-lose-jobs.

Kustec, Stan. (2012, June). The role of migrant labour supply in the Canadian labour market. [PDF] Ottawa: Citizenship and Immigration Canada. Retrieved July 25, 2014, from http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/resources/research/2012-migrant/documents/pdf/migrant2012-eng.pdf.

Labour Market Research and Forecasting Policy Research Directorate. (2011a). Canadian occupational projection system 2011 projections: Job openings 2011-2020. Employment and social development Canada. Ottawa. Retrieved July 25, 2014, from http://www23.hrsdc.gc.ca/l.3bd.2t.1ilshtml@-eng.jsp?lid=17&fid=1&lang=en.

Labour Market Research and Forecasting Policy Research Directorate. (2011b.) Industrial outlook – 2011-2020. Employment and social development Canada. Ottawa. Retrieved July 25, 2014, from http://www23.hrsdc.gc.ca/l.3bd.2t.1ilshtml@-eng.jsp?lid=14&fid=1&lang=en.

Marx, Karl. (1977). Economic and philosophical manuscripts. In David McLellan (Ed.), Karl Marx: Selected writings (pp. 75–112). Oxford: Oxford University Press. (Original work published 1932)

Mas, Susana. (2014, June 20). Temporary foreign worker overhaul imposes limits, hikes inspections: Cap on low-wage temporary workers to be phased in over 2 years. CBC News. Retrieved July 25, 2014, from http://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/temporary-foreign-worker-overhaul-imposes-limits-hikes-inspections-1.2682209.

Statistics Canada. (2011). Women in Canada: A gender based statistical report. [PDF] Ottawa: Statistics Canada. Retrieved July 25, 2014, from http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/89-503-x/89-503-x2010001-eng.pdf.

Uppal, Sharanjit and Sébastien LaRochelle-Côté. (2014, April). Changes in the occupational profile of young men and women in Canada. [PDF] Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 75‑006‑X. Retrieved July 25, 2014, from http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/75-006-x/2014001/article/11915-eng.pdf.

Wang, Wendy and Kim Parker. (2011,August 17). Women see value and benefit of College; Men lag behind on both fronts. Pew Social and Demographic Trends. Retrieved January 30, 2012, from http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2011/08/17/women-see-value-and-benefits-of-college-men-lag-on-both-fronts-survey-finds/5/#iv-by-the-numbers-gender-race-and-education.

Yalnizyan, Armine. (2010, August). The problem of poverty post-recession. [PDF] Ottawa: Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. Retrieved July 25, 2014, from http://www.policyalternatives.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/publications/reports/docs/Poverty%20Post%20Recession.pdf.

Yssaad, Lahouaria. (2012, December). The immigrant labour force analysis series: The Canadian immigrant labour market. [PDF] Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 71-606-X. Retrieved July 25, 2014, from http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/71-606-x/71-606-x2012006-eng.pdf.

Image Attributions

Figure 12._ The Toronto Stock Exchange by Paul B Toman (http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The-toronto-stock-exchange.jpg) used under CC BY SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en)

Long Descriptions

| Year | 1976 | 1978 | 1980 | 1982 | 1984 | 1986 | 1988 | 1990 | 1992 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage | 13.5 | 12.5 | 12 | 14 | 16.1 | 14 | 12.1 | 14 | 15.1 |

| Year | 1994 | 1996 | 1998 | 2000 | 2002 | 2004 | 2006 | 2008 | |

| Percentage | 16.1 | 18.2 | 15.8 | 14 | 12.3 | 13.1 | 11.5 | 9.1 |

Solutions to Chapter Quiz

1 b, | 2 c, | 3 c, | 4 d, | 5 c, | 6 a, | 7 b, | 8 a, | 9 c, | 10 a, | 11 c

[Return to Quiz]