6 Social Inequality in Canada

Learning Objectives

6.1. What Is Social Inequality?

- Break the concept of social inequality into its component parts: social differentiation, social stratification, and social distributions of wealth, income, power, and status.

- Define the difference between equality of opportunity and equality of condition.

- Distinguish between caste and class systems.

- Distinguish between class and status.

- Identify the structural basis for the different classes that exist in capitalist societies.

6.2. Social Inequality and Mobility in Canada

- Define the difference between relative and absolute poverty.

- Describe the current trend of increasing inequalities of wealth and income in Canada.

- Distinguish the the differences between Marx’s and Weber’s definitions of social class and explain why they are significant.

- Characterize the social conditions of the owning class, the middle class, and the traditional working class in Canada.

- Apply the research on social mobility to the question of whether Canada is a meritocracy.

- Recognize cultural markers that are used to display class identity.

6.3. Global Stratification and Inequality

- Define global inequality.

- Describe different sociological models for understanding global inequality.

- Understand how sociological studies identify worldwide inequalities.

Introduction to Social Inequality in Canada

When he died in 2008, Ted Rogers Jr., then CEO of Rogers Communications, was the fifth-wealthiest individual in Canada, holding assets worth $5.7 billion. In his autobiography (2008) he credited his success to a willingness to take risks, work hard, bend the rules, be on the constant look-out for opportunities, and be dedicated to building the business. He saw himself as a self-made billionaire who started from scratch, seized opportunities, and created a business through his own initiative.

The story of Ted Rogers is not exactly rags-to-riches, however. His grandfather, Albert Rogers, was a director of Imperial Oil (Esso) and his father, Ted Sr., became wealthy when he invented an alternating current vacuum tube for radios in 1925. Ted Rogers Sr. went on to manufacturing radios, owning a radio station, and acquiring a TV broadcasting licence.

However, Ted Sr. died when Ted Jr. was five years old, and the family businesses were sold. The family was still wealthy enough to send him to Upper Canada College, the famous private school that educates children from some of Canada’s wealthiest families. Ted seized the opportunity at Upper Canada to make money as a bookie, taking bets on horse racing from the other students. Then he attended Osgoode Hall Law School, where reportedly his secretary went to classes and took notes for him. He bought an early FM radio station when he was still in university and started in cable TV in the mid-1960s. By the time of his death, Rogers Communications was worth $25billion.

At the other end of the opportunity spectrum are the Indigenous gang members in the Saskatchewan Correctional (CBC, 2010). CBC noted that 85 percent of the inmates in the prison were of Indigenous descent. The statistical profile of Indigenous Saskatchewan youth is grim, with high levels of school attrition,domesticabuse,drugdependencies,andchildpoverty.

In some ways the Indigenous inmates interviewed were like Ted Rogers: they were willing to seize opportunities, take risks, bend rules, and apply themselves to their vocations. They too aspired to get the money that would give them the freedom to make their own lives. However, as one of the inmates put it, “the only job I ever had was selling drugs” (CBC, 2010). The consequence was falling into a lifestyle that led to joining a gang, being kicked out of school, developing issues with addiction, and eventually getting arrested and incarcerated. Unlike Ted Rogers, however, the inmate added, “I didn’t grow up with the best life” (CBC, 2010).

How do we make sense of the different stories? Canada is supposed to be a country where individuals can work hard to get ahead. It is an “open” society. There are no formal class, gender, racial, ethnic, geographical, or other boundaries that prevent people from rising to the top. People are free to make choices. But does this explain the difference in life chances that divide the Indigenous youth from the Rogers family? What determines a person’s social standing? And how does social standing expand or limit a person’s choices?

6.1. What Is Social Inequality?

Sociologists use the term social inequality to describe the unequal distribution of resources, rewards and positions in a society. When a social category like class, occupation, gender, or race puts people in a position from which they can claim a greater share of resources or services, this becomes the basis of social inequality.

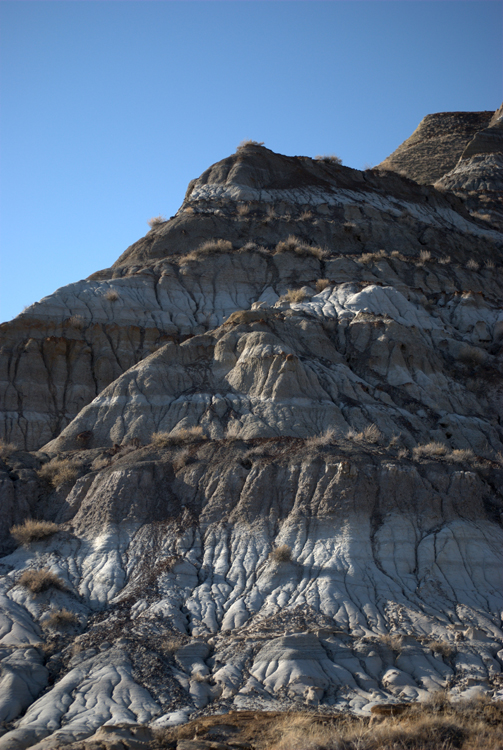

The term social stratification refers to an institutionalized system of social inequality. In social stratification, the divisions and relationships of social inequality have solidified into a system that determines who gets what, when, and why.

The distinct horizontal layers found in rock, called “strata,” help visualize stratification of social structure. Society’s layers are made of people, and society’s resources are distributed unevenly throughout the layers. The people who have more resources represent the top layer of social stratification. Other groups, with progressively fewer and fewer resources, represent the lower layers of our society. Social stratification assigns people to socioeconomic strata based on factors like wealth, income, race, education, and power. Sociologists ask how systems of stratification are formed. What is the basis of systematic social inequality in society?

Many Canadians believe in equality of opportunity and assume everyone has an equal chance at success. Equality of opportunity exists when people have the same chance to pursue economic or social rewards. This is often seen as a function of equal access to education, meritocracy (where individual merit determines social standing), and formal or informal measures to eliminate social discrimination. Sociologists debate whether Canadians have equality of opportunity.

Ted Rogers’ story illustrates the belief in equality of opportunity. In his personal narrative, hard work and talent — not inherent privilege, birthright, prejudicial treatment, or societal values— determined his social rank. This emphasis on self-effort is based on the belief that people individually control their own social standing, a key piece in the idea of equality of opportunity.

Most people connect inequalities of wealth, status, and power to the individual characteristics of those who succeed or fail. The story of the Indigenous gang members, although it is also a story of personal choices, disproves that belief. The type of choices available to the Indigenous gang members are very different than those available to the Rogers family.

Social inequality is not about individual inequalities, but about systematic inequalities based on group membership, class, gender, ethnicity, and other variables that structure access to rewards and status. Sociologists examine the structural conditions of social inequality. There are differences in individuals’ abilities and talents. The larger question, however, is how inequality becomes systematically structured in economic, social, and political life. Who gets the opportunities to develop their abilities and talents, and who does not? Where does “ability” or “talent” come from? Because we live in a society that emphasizes the individual — individual effort, individual morality, individual choice, individual responsibility, individual talent, etc. — it is often difficult to see how life chances are socially structured.

In most modern societies, stratification is defined by differences in

- wealth, the net value of money and assets a person has, and

- income, a person’s wages,salary,orinvestmentdividends.

- power (how many people a person must take orders from versus how many people a person can give orders to) and

- status (the degree of honour or prestige one has in the eyes of others).

These four factors merge to define individuals’ social standing within a hierarchy. Cultural attitudes and beliefs support and perpetuate social inequalities.

Systems of Stratification

Sociologists distinguish between two types of systems of stratification.

- Closed systems accommodate little change in social position. They do not allow people to shift levels and do not permit social relations between levels.

- Open systems, based on achievement, allow movement and interaction between layers and classes.

Different systems reflect, emphasize, and foster certain cultural values, and shape individual beliefs. This difference in stratification systems can be examined by the comparison between class systems and caste systems.

The Caste System

Caste systems are closed stratification systems in which people can do little or nothing to change their social standing. A caste system is one in which people are born into their social standing and remain in it their whole lives. It is based on fixed or rigid status distinctions, rather than economic factors. Status is defined by the level of honour or prestige received by membership in a group.

Sociologists distinguish between ascribed status — a status received by being born into a category or group (hereditary position, gender, race, etc.) —and achieved status — a status received through individual effort or merits (occupation, educational level, moral character, etc.). Caste systems are based on a hierarchy of ascribed statuses, based on being born into fixed caste groups.

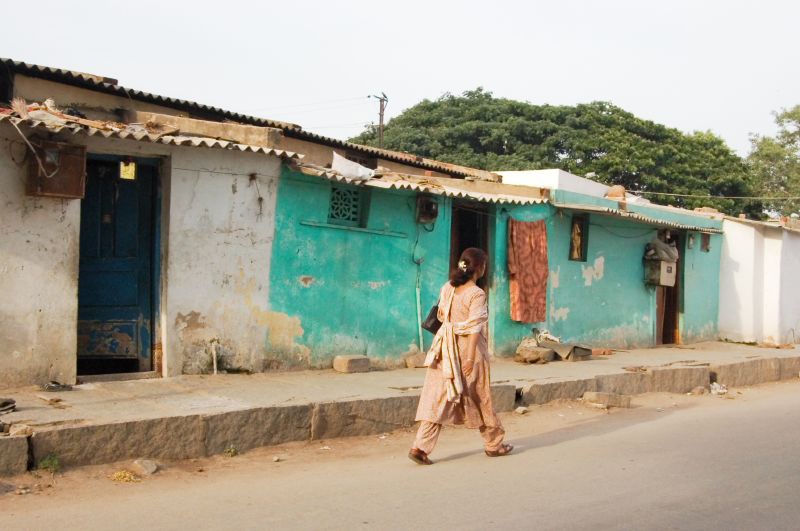

The caste system existed in India from 4,000 years ago until the 20th century. In the Hindu caste tradition, people were also expected to work in the occupation of their caste and marry according to their caste. Accepting this social standing was considered a moral duty. Cultural values and economic restrictions reinforced the system. Caste systems promote beliefs in fate, destiny, and the will of a higher power, rather than valuing individual freedom. A caste society socialized individuals to accept his or her social standing.

Although the caste system in India has been officially dismantled, its residual presence in Indian society is deeply embedded. In rural areas, aspects of the tradition are more likely to remain, while urban centres show less evidence of this past. In India’s larger cities, people now have more opportunities to choose their own career paths and marriage partners. As a global centre of employment, corporations have introduced merit-based hiring and employment to the nation.

The Class System

A class system is based on both social factors and individual achievement. It is at least a partially open system. A class consists of a set of people who have the same relationship to the means of production, that is, to the ways used to produce the goods and services needed for survival: tools, technologies, resources, land, workplaces, etc. In Karl Marx’s analysis, class systems form around the institution of private property, dividing those who own or control productive property from those who do not, who survive through their labour.

Social class has both a strictly material quality relating to these definitions of individuals’ positions within a given economic system, and a social quality relating to the formation of common class interests, political divisions, life styles and consumption patterns, and “life chances” (Weber 1969). Whether defined by material or social characteristics however, the main social outcome of the class structure is inequality in society.

In capitalism, the principle class division is between

- the capitalist class who live from the proceeds of owning or controlling property (capital assets like factories and machinery, or capital itself in the form of investments, stocks, and bonds) and

- the working class who live from selling their labour to the capitalists for a wage.

Marx used terms like bourgeoisie, proletariat and lumpenproletariat (the sub-proletariat).

The bourgeoisie include shopkeepers, farmers, and contractors who own some property and perhaps employ a few workers but still rely on their own labour to survive. The proletariat are the poorer workers. The lumpenproletariat are the chronically unemployed or irregularly employed who are in and out of the workforce. They are what Marx referred to as the “reserve army of labour,” a pool of potential labourers who are not always needed in the economy.

In a class system, social inequality is structural, meaning that it is “built in” to the organization of the economy. The relationship to the means of production means whether someone is an owner or not. The relationship to the means of production creates a pattern of social relationships that exist outside of individuals’ choice. The bourgeoisie is driven to accumulate capital and increase profit. They achieve this in a competitive marketplace by reducing the cost of production by lowering the cost of labour (by reducing wages, moving production to lower wage areas, or replacing workers with labour-saving technologies). This contradicts the interests of the proletariat who want to establish a good standard of living by maintaining the level of their wages and the level of employment in society.

The class interests clash and define a pattern of management-labour conflict and political differences.

However, unlike caste systems, class systems are open. People are at least formally free to gain a different level of education or employment than their parents. They can move up and down the stratification system. They can also socialize with and marry members of other classes, moving from one class to another. Individuals can move up and down the class hierarchy, even while the class categories and the class hierarchy remain stable.

In a class system, occupation is not fixed at birth. Though family and other social models guide a person toward a career, personal choice plays a role. For example, Ted Rogers Jr. chose a career in media like his father but managed to move from a position of relative wealth and privilege to be the fifth wealthiest bourgeois in the country.

6.2. Social Inequality and Mobility in Canada

Standard of Living

In the last century, Canada has seen a steady rise in standard of living, wealth available to acquire material necessities and comforts. The standard of living is based on factors such as income, employment, class, poverty rates, and affordability of housing. Because standard of living is closely related to quality of life, it can represent factors such as the ability to afford a home, own a car, and take vacations. Access to a standard of living that enables equal participation in community life is not equally distributed, however.

Canadians may not have to live in absolute poverty—“a severe deprivation of basic human needs, including food, safe drinking water, sanitation facilities, health, shelter, education and information” (United Nations, 1995)—to be marginalized and socially excluded. Relative poverty refers to the minimum amount of income or resources needed to be able to participate in the “ordinary living patterns, customs, and activities” of a society (Townsend, 1979).

In Canada, a small portion of the population has the highest standard of living. Statistics Canada data showed that 10 percent of the population held 58 percent of our nation’s wealth in 2005 (Osberg, 2008). In 2007, the richest 1 percent took 13.8 percent of the total income earned by Canadians (Yalnizyan, 2010). In 2010, the median income earner in the top 1 percent earned 10 times more than the median income earner of the other 99 percent (Statistics Canada, 2013).

Wealthy people receive the most schooling, have better health, and consume the most goods and services. Wealthy people also have decision-making power. One aspect of their decision-making power comes from their positions as owners corporations and banks. They can grant themselves salary raises and bonuses. By 2010, only two years into the economic crisis of 2008, the pay of CEOs at Canada’s top 100 corporations jumped by 13 percent (McFarland, 2011), while negotiated wage increases in 2010 amounted to only 1.8 percent (HRSDC, 2010).

Many people think of Canada as a middle-class society. They think a few people are rich, a few are poor, and most are well off, existing in the middle of the social strata. But as the data above indicate, the distribution of wealth is not even. Millions of women and men struggle to pay rent, buy food, and find work that pays a living wage. Moreover, the share of the total income claimed by those in the middle-income ranges has been shrinking since the early 1980s, while the share taken by the wealthiest has been growing (Osberg, 2008).

For several decades, between 1946 and 1981, changes in income inequality were small even though the Canadian economy was massively transformed:

- the economy moved from an agricultural base to an industrial base;

- the population urbanized and doubled in size;

- the overall production of wealth measured by gross domestic product (GDP ) increased by 4.5%; and per capita output increased by 227% (Osberg, 2008).

Economic inequality not change during this period of massive transformation.

From 1981 until the present, during another period of rapid and extensive economic change, the overall production of wealth continued to expand. However, economic inequality increased dramatically. What happened?

Between 1946 and 1981 real wages increased in pace with economic growth. But since 1981 only the top 20% of families have seen increase in real income, and the very wealthy have seen huge increases. The taxable income of the top 1% of families increased by 80% between 1982 and 2004 (Obsberg, 2008).

Neoliberal policies of reduced state spending and increased tax cuts have been major differences between these two eras. The neoliberal theory that benefits of tax cuts to the rich would “trickle down” to the middle class and the poor has proven false. The biggest losers in neoliberal policy are the very poor. As Osberg notes, it was not until the 1980s and 1990s that the homeless—those forced to beg in the streets and those dependent on food banks—began to appear in Canada in significant numbers (2008).

The idea that equality of opportunity—a meritocracy leads to social mobility, movement from one social position to another —is debatable. Degrees of social inequality also vary significantly between regions.

Making Connections: Sociological Research

Measuring Levels of Poverty

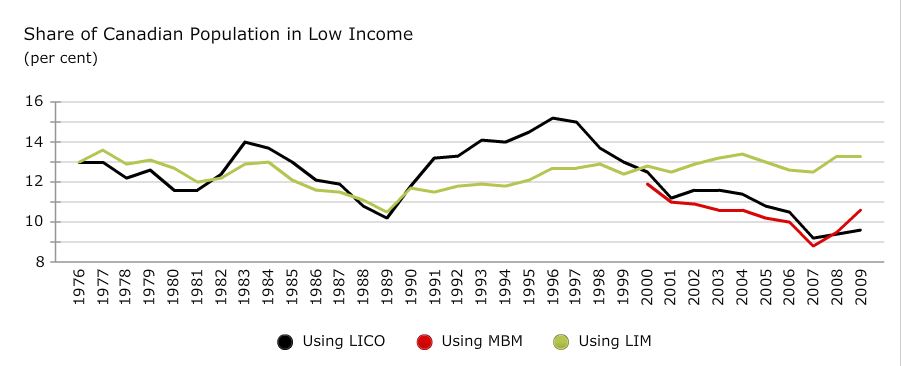

Statistics Canada produces two relative measures of poverty: the low income measure (LIM) and the low income cut-off (LICO) measure. Human Resources and Skills Development Canada has developed an absolute measure: the market basket measure (MBM).

Low income measure: The LIM is defined as half the median family income. A person whose income is below that level is said to be in low income. The LIM is adjusted for family size.

Low income cut-off: The LICO is the income level below which a family would devote at least 20 percentage points more of their income to food, clothing, and shelter than an average family would. People are said to be in the low-income group if their income falls below this threshold. The threshold varies by family size and community size, as well as if income is calculated before or after taxes. For example, a single individual in Toronto would be said to be living in low income if his or her 2009 after-tax income was below $18,421.

Market basket measure: The MBM is a measure of the disposable income a family would need to be able to purchase a basket of goods that includes food, clothing, shelter, transportation, and other basic needs. The dollar value of the MBM varies by family size and composition, as well as community size and location. MBM data are available since 2000 only.

The three measures produce different results. In 2009, according to each measure, the following numbers of Canadians were living in low income:

- LICO—3.2 million (9.6 per cent of the population)

- MBM—3.5 million (10.6 per cent)

- LIM—4.4 million (13.3 per cent)

Table 6.1 shows how the three measures also produce different results over time. Using the LICO measure results in a decreasing share of people in low income from 1996 to 2007, followed by a slight upturn in 2008 and 2009. The LIM measure results in a share of people in low income that has increased since 1990. The MBM, which has data starting only in 2000, shows results similar to the LICO but with a sharper upturn in 2008 and 2009.

Social Classes in Canada

Does a person’s appearance indicate class? Do you know a person’s income by their car? There was a time in Canada when class was more visibly apparent. In some countries, like the United Kingdom, social class can still be guessed by differences in schooling, lifestyle, and even accent. In Canada, however, it is harder to determine class from outward appearances.

Some analyses of class emphasize variables like wealth, income, education, and occupation. Class stratification is not just determined by a group’s economic position but by the prestige of the group’s occupation, education, consumption, and lifestyle. It is a matter of status—the level of honour or prestige because of social position.

Some sociologists talk about upper, middle, and lower classes (with many subcategories within them) in a way that combine status categories with class categories. This is socio-economic status (SES), social position relative to others based on income, education, and occupation. For example, although plumbers might earn more than high school teachers, the status division between blue-collar work (people who “work with their hands”) and white-collar work (people who “work with their minds”) means that plumbers may be characterized as lower class but teachers as middle class. The division of classes into upper, middle, and lower can be arbitrary.

Social class is complex. Social class has at least three objective components:

- a group’s position in the occupational structure,

- a group’s position in the authority structure (i.e., who has authority over whom), and

- a group’s position in the property structure (i.e., ownership or non-ownership of capital).

Social class also has a subjective component involving lifestyle and how people perceive their place in the class hierarchy.

One way of distinguishing the classes focuses on the authority structure. Classes can be divided according to how much relative power and control members of a class have over their lives.

- The owning class not only have power and control over their own lives, their economic position gives them power and control over others’ lives as well.

- A “middle class” is composed of small business owners and educated, professional, or administrative labour, not because they have control other strata of society, but they do exert some control over their own work.

- The traditional working class has little control over their work or lives.

Below, we will explore the major divisions of Canadian social class and their key subcategories.

The Owning Class

The owning class is the powerful “elite.” In Canada, the richest 86 people (or families) account for 0.002 percent of the population, but in 2012 they had accumulated the equivalent wealth of the lowest 34 percent of the country’s population (McDonald, 2014). The combined net worth of these 86 families added up to $178 billion in 2012, which equalled the net worth of the lowest 11.4 million Canadians. In terms of income, in 2007 the average income of the richest 0.01 percent of Canadians was $3.833 million (Yalnizyan, 2010).

In addition to material goods, money also provides access to power. Canada’s owning class has a lot of power. As corporate leaders, their decisions affect the jobs of millions. As media owners, they shape the nation’s identity. They run the major network television stations, radio broadcasts, newspapers, magazines, publishing houses, and sports franchises. As philanthropists, they support social causes. They also fund think tanks like the C. D. Howe Institute, AIMS and the Fraser Institute. Such think tanks usually promote the interests of business elites. As campaign contributors, they influence and fund politicians, usually to protect their own economic interests.

Canadian society has historically distinguished between “old money” (inherited wealth passed from one generation to the next) and “new money” (wealth you have earned and built yourself). While both types may have equal net worth, they have traditionally held different social standing. People of old money, firmly situated in the upper class for generations, have held high prestige. Their families have socialized them to know the customs, norms, and expectations that come with wealth. Often, the very wealthy do not work for wages. Some study business or become lawyers to manage the family fortune.

New money members of the owning class may not know the customs of the elite. They have not gone to the most exclusive schools. They have not established old-money social ties. People with new money might flaunt their wealth, buying sports cars and mansions, but they might still exhibit behaviours attributed to the middle and lower classes. For example, Toronto politicians Rob and Doug Ford were estimated to hold family assets worth $50 million, yet they presented themselves as just “average guys” who stand with their blue-collar constituents against “rich elitist people” (McArther, 2013; Warner, 2014). Rob Ford’s infamous crack cocaine smoking, public binge drinking, and use of foul language did not make him at home on old money circles.

The Middle Class

Many people call themselves middle class, but there are different ideas about what that means. People with annual incomes of $150,000 call themselves middle class, as do people who annually earn $30,000. That helps explain why some sociologists divide the middle class into upper and lower subcategories. These divisions are based on levels of status defined by levels of education, types of work, cultural capital, and the lifestyles.

Upper-middle-class people tend to hold bachelor’s and postgraduate degrees in subjects such as business, management, law, or medicine that lead to occupations in the professions. Professions are occupations that claim high levels of specialized technical and intellectual expertise and are regulated by autonomous professional organizations (like the Canadian Medical Association or legal bar associations). Lower-middle-class members hold bachelor’s degrees or diplomas from two-year community colleges that lead to various types of white collar, service, administrative, or paraprofessional occupations.

Comfort is a key concept to the middle class. Middle-class people work hard and live comfortable lives. Upper-middle-class people tend to pursue careers that earn even more comfortable incomes. They provide their families with large homes and expensive cars. They may go skiing or boating on vacation. Their children receive elite educations (Gilbert, 2010).

In the lower middle class, people hold jobs supervised by members of the upper middle class. They fill technical, lower-level management or administrative support positions. Compared to traditional working-class work, lower- middle-class jobs have more prestige and come with slightly higher pay cheques. With these incomes, people can afford a decent, mainstream lifestyle, but they struggle to maintain it. They generally do not have enough income

to build significant savings. In addition, their grip on class status is more precarious than in the upper tiers of the class system. When budgets are tight, lower-middle-class people are often lose their jobs.

The Traditional Working Class

The traditional working class is sometimes also referred to as being part of the lower class. Just like the middle and upper classes, the lower class can be divided into subsets: the working class, the working poor, and the underclass. Compared to the middle class, traditional working-class people have less of an educational background and usually earn smaller incomes. While there are many working-class trades that require skill and pay middle-class wages, the majority often work jobs that require little prior skill or experience, doing routine tasks under close supervision.

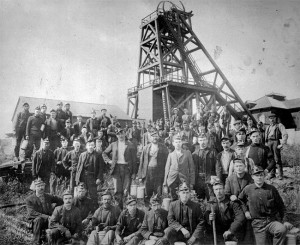

Traditional working-class people, the highest subcategory of the lower class, are usually equated with blue-collar types of jobs: “wage-workers who are engaged in the production of commodities, the extraction of natural resources, the production of food, the operation of the transportation network required for production and distribution, the construction industry, and the maintenance of energy and communication networks” (Veltmeyer, 1986, p. 83). The work is considered blue collar because it is hands-on and often physically demanding. The term “blue collar” comes from the traditional blue coveralls worn by manual labourers.

The Working Poor

The working poor, like some sections of the working class, unskilled, low-paying employment. However, their jobs rarely offer benefits such as retirement planning, and their positions are often seasonal or temporary. They work as migrant farm workers, house cleaners, and day labourers. Some are high school dropouts. Some are illiterate, unable to read job ads. Many do not vote because they do not believe that any politician will help change their situation (Beeghley, 2008).

How can people work full time and still be poor? Even working full time, more than a million of the working poor earn incomes too meagre to support a family. In 2012, 1.8 million working people (including 540,000 working full-time year round) earned less than Statistic Canada’s low income cut-off level, which defines poverty in Canada (Johnstone & Cooper, 2013). Minimum wage varies from province to province. However, a minimum wage is not necessarily a living wage. A living wage is the amount needed to meet a family’s basic needs and enable them to participate in community life (Johnstone & Cooper, 2013). Even for a single person, minimum wage is low. A married couple with children will have a hard time covering expenses.

The underclass live mainly in inner cities. Many are unemployed or underemployed. Those who hold jobs typically perform menial tasks for little pay. Some of the underclass are homeless. Social assistance provides a much-needed support through food assistance, medical care, housing, etc. for some.

Social Mobility

Social mobility refers to the ability to change positions within a social stratification system. This is a key concept in determining whether inequalities of condition limit people’s life chances or whether equality of opportunity exists in a society. A high degree of social mobility, upwards or downwards, would suggest that the stratification system of a society is open, that there is equality of opportunity.

Upward mobility refers to an upward shift in social class. Canadians celebrate the rags- to-riches achievements of celebrities like Guy Laliberté who went from street busking in Quebec to being the CEO of Cirque du Soleil, with a net worth of $2.5 billion. Actor and comedian Jim Carey lived with his family in camper van growing up in Scarborough, Ontario. Ron Joyce was a beat policemen in Hamilton before he co-founded Tim Hortons. CEO of Magna International Frank Stronach immigrated to Canada from Austria in 1955 with only $50. There are many stories of people from modest beginnings rising to fame and fortune. But the number of people who move from poverty to wealth is very small. Still, upward mobility is not only about becoming rich and famous. In Canada, people who earn a university degree, get a good job, or marry someone with a good income may move up socially.

Downward mobility indicates a lowering of social class. Some people move downward because of business setbacks, unemployment, or illness. Dropping out of school, losing a job, or becoming divorced may result in a loss of income or status and, therefore, downward social mobility.

Intergenerational mobility explains a difference in social class between different generations of a family. For example, an upper-class executive may have parents who belonged to the middle class. In turn, those parents may have been raised in the lower class. Patterns of intergenerational mobility can reflect long-term societal changes.

Intragenerational mobility describes a difference in social class between different members of the same generation. For example, the wealth and prestige experienced by one person may be quite different from that of his or her siblings.

Structural mobility happens when societal changes enable a whole group of people to move up or down the social class ladder. Structural mobility is attributable to changes in society, not individual changes.

In the first half of the 20th century industrialization expanded the Canadian economy, which raised the standard of living and led to upward structural mobility. In today’s work economy, the recession and the outsourcing of jobs overseas have contributed to high unemployment rates. Many people have experienced economic setbacks, creating a wave of downward structural mobility.

Some Canadians believe that people move up in class because of individual efforts and move down by their own acts. Ideally, access to rewards would exactly equal personal efforts and merits. Class position or other social characteristics (gender, race, ethnicity, etc.) would not affect the relationship between merit and rewards.

Other Canadians believe that equality of opportunity is a myth. This myth keeps people motivated to work hard and accept social inequality as the outcome of personal achievement. The equality of opportunity ideal hides structural inequality in society. The rich stay rich, and the poor stay poor.

Sociology studies about social mobility in Canada suggest there is some truth to both views.

Social mobility is measured by comparing either the occupational status or earnings between parents and children. If children’s earnings or status remain the same as their parents, then there is no social mobility. If children’s earnings or status moves up or down with respect to their parents, then there is social mobility.

Canada has a relatively high rate of social mobility and equality of opportunity compared to the United States, where almost 50 percent of sons remain at the same income level as their fathers. In an international comparison, the United Kingdom had even lower social mobility than the United States, while Finland, Norway, and Denmark had greater social mobility than Canada. (Corak et. Al, 2010).

One of the key factors that distinguishes Canada’s social mobility from that of the United States is that the United States has a much greater degree of social inequality to start. The higher degree of social inequality is linked to lower degrees of social mobility. (Corak et al., 2010).

However, the data also show that Canada does not have true equality of opportunity. Class background significantly affects chances to get ahead. For example, the chance that a son born to a father in the 30 to 50 percent ranges of income would move up into the top 50 percent of income earners was about 50 percent (Yalnizyan, 2007). In contrast, a son in the bottom 20 percent of income earners had only a 38 percent chance of moving into the top 50 percent of income earners. For the bottom 20 percent of families, 62 percent of sons remained within the bottom 50 percent of income earners (Corak et al., 2010).

Class Traits

Class traits, also called class markers, are the typical behaviours, customs, and norms that define each class. They define a crucial subjective component of class identities. Class traits indicate the level of exposure a person has to a wide range of cultural resources. Class traits also indicate the amount of resources a person has to spend on items like hobbies, vacations, and leisure activities.

People may associate the upper class with enjoyment of costly, refined, or highly cultivated tastes — expensive clothing, luxury cars, high-end fundraisers, and opulent vacations. People may also believe that the middle and lower classes are more likely to enjoy camping, fishing, or hunting, shopping at large retailers, and participating in community activities. It is important to note that while these descriptions may be class traits, they may also simply be stereotypes. Moreover, just as class distinctions have blurred in recent decades, so too have class traits. A very wealthy person may enjoy bowling as much as opera. A factory worker could be a skilled French cook. Pop star Justin Bieber might dress in hoodies, ball caps, and ill fitting clothes, and a low-income hipster might own designer shoes.

These days, individual taste does not necessarily follow class lines. Still, you are not likely to see someone driving a Mercedes living in an inner-city neighbourhood. And most likely, a resident of a wealthy gated community will not be riding a bicycle to work. Class traits often develop based on cultural behaviours that stem from the resources available within each class.

Making Connections: Sociological Research

Turn-of-the-Century “Social Problem Novels”: Sociological Gold Mines

Class distinctions were sharper in the 19th century and earlier, in part because people easily accepted them. The ideology of social order made class structure seem natural, right, and just.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, American and British novelists played a role in changing public perception. They published novels in which characters struggled to survive against a merciless class system. These dissenting authors used gender and morality to question the class system and expose its inequalities. They protested the suffering of urbanization and industrialization, drawing attention to these issues.

These “social problem novels,” sometimes called Victorian realism, forced middle-class readers into an uncomfortable position: The readers had to question and challenge the natural order of social class.

For speaking out so strongly about the social issues of class, authors were both praised and criticized. Most authors did not want to dissolve the class system. They wanted to bring about an awareness that would improve conditions for the lower classes, while maintaining their own higher-class positions (DeVine, 2005).

Soon, middle-class readers were not their only audience. In 1870, Forster’s Elementary Education Act required all children aged five through 12 in England and Wales to attend school. The act increased literacy levels among the urban poor, causing a rise in sales of cheap newspapers and magazines. Additionally, the increasing number of people who rode public transit systems created a demand for “railway literature,” as it was called (Williams, 1984). These reading materials are credited with the move toward democratization in England. By 1900 the British middle class established a rigid definition for itself, and England’s working class also began to self-identify and demand a better way of life.

Many of the novels of that era are seen as sociological goldmines. They are studied as existing sources because they detail the customs and mores of the upper, middle, and lower classes of that period in history.

Examples of “social problem” novels include Charles Dickens’s (1812-1870) The Adventures of Oliver Twist (1838), which shocked readers with its brutal portrayal of the realities of poverty, vice, and crime. Thomas Hardy’s (1840-1928) Tess of the d’Urbervilles (1891) was considered revolutionary by critics for its depiction of working-class women (DeVine, 2005), and American novelist Theodore Dreiser’s (1871-1945) Sister Carrie (1900) portrayed an accurate and detailed description of early Chicago.

6.3. Global Stratification and Inequality

Global stratification compares the wealth, economic stability, and power of countries across the world. Global stratification highlights worldwide patterns of social inequality.

In the early years of civilization, hunter-gatherer and agrarian societies lived off the Earth, rarely interacting with other societies. When explorers began travelling, societies began trading goods as well as ideas and customs.

In the 19th century, the Industrial Revolution created great wealth in Western Europe and North America. Mechanical inventions sent large numbers of people to work in factories and coal mines — not only men, but also women and children. By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, industrial technology had gradually raised the standard of living for many people in the United States and Europe.

The Industrial Revolution also saw the rise of vast inequalities between countries that were industrialized and those that were not. As some nations embraced technology and increased wealth and goods, others maintained traditional ways. The wealth gap widened with nonindustrialized nations. Researchers suggest that the disparity also resulted from power differences. Critical sociology believes that industrializing nations took advantage of the resources of traditional nations. As industrialized nations became rich, other nations became poor (Rostow, 1960).

Sociologists studying global stratification analyze economic comparisons between nations. Income, purchasing power, and wealth are used to calculate global stratification. Global stratification also compares the quality of life.

Poverty levels vary greatly. The poor in wealthy countries like Canada or Europe are better off than the poor in countries such as Mali or India. In 2002 the United Nations implemented the Millennium Project, an attempt to cut poverty worldwide by the year 2015. To reach the project’s goal, planners in 2006 estimated that industrialized nations must set aside 0.7 percent of their gross national income — the total value of the nation’s goods and services — to aid developing countries (Landler & Sanger, 2009; Millennium Project, 2006). The project was successful in reaching its target of cutting extreme poverty by half — the number of people living on $1.25/ day or less — but fell short of halving the number of people suffering from hunger. Undernourishment in developing regions fell from 23.3% to 12.9% (United Nations, 2015).

Neoliberalism and Globalization

As you read in the chapter on culture, globalization refers to the integration of international trade and finance.

Globalization intensified after World War II, and especially in the late 20th century. New technologies allowed large amounts of capital and goods to circulate globally. The globalization of investment and production means that capital can move freely around the world to where labour costs are cheapest and profit greatest. Corporate, political, environmental decisions are no longer based on state boundaries. This lessens the ability of national governments to control policy.

Neoliberalism is a set of policies in which the state reduces its role in providing public services, regulating industry, redistributing wealth, and protecting “the commons” —the collective property that exists for everyone to share (the environment, public and community facilities, airwaves, etc.). Neoliberalism is not only a response to the economic crises and reduction in profits within a country; it is also a response to the competition for globalized capital. Neoliberal policy aims to attract increasingly fickle global capital by making entire countries more “competitive.” The result, as David Harvey argues, has been to massively shift the balance of power to the global economic elites (2005, pp. 16–19). Wealth has been redistributed upwards.

Globalization puts pressure on government policy. Changes in government policy contribute to growing inequality in Canada. Canada moved from a welfare state model of resource redistribution to a neoliberal model of free market resources distribution.

What is the welfare state? After World War II a kind of labour-management “accord” existed in Canada. This involved the recognition of labour unions, the mediation of the state in capital/labour disputes, the use of taxes to address economic recessions, and a social safety. This set of policies is known as the welfare state. In a high wage/high consumption economy, the ability of individuals to continue to consume was important, so unemployment insurance, pensions, health care, and disability benefits were important. This labour-management accord also reaffirmed the rights of private property or capital to introduce new technology, to reorganize production, and to invest wherever they pleased. Therefore, it was not a system of economic democracy or socialism. Nevertheless, the claims of full employment, continued prosperity, and the creation of a “just society” seemed possible within the capitalist economic system.

When the welfare state system began to shown strain in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the relationship between the state and the economy began to change again. With a global economy of lean production and precarious employment, the state began withdrawing from universal social services and social security. Neoliberalism describes the new thinking by government. Neoliberalism abandons the interventionist model of the welfare state to emphasize the use of “free market” to regulate society.

Neoliberalist policies are promoted as ways of addressing the “inefficiency of big government,” the “burden on the taxpayer,” the “need to cut red tape,” and the “culture of entitlement and welfare dependency.” Neoliberalism favours competitive marketplace over government regulation. The market is said to promote efficiency, lower costs, good decision making, non-favouritism, and a disciplined work ethic, etc.

The facts often tell a different story. For example, government-funded health care in Canada costs far less per person than private health care in the United States (OECD, 2015). Norway has much higher taxes than Canada, much lower unemployment, lower income inequality, lower inflation, better public services, a higher standard of living. Norway nevertheless has a globally competitive corporate sector with substantial state control (especially in the areas of oil and gas production, which is 80% owned by the Norwegian state) (Campbell, 2013). Deregulation polices caused the financial crisis of 2008. Some neoliberal economists now acknowledge that the free market model is flawed (CBC News, 2013).

The new global capitalism and politics has been described as the reemergence of empire (Hardt & Negri, 2000). Rather than a system of independent nation-states, the world can be seen as a single unit within which state sovereignty has been transferred to a higher entity (Negri, 2004, p. 59). Trade agreements no longer restricttheflowofcapitalandgoods. Frequentglobal“policeactions” and trade embargoes by various “coalitions of the willing” enforce peace or intervene in domestic policy (in, for example, Iraq, Yugoslavia, Somalia, Afghanistan, Iran, Libya, and Syria). Similarly, the Kyoto Protocol on climate change or the Ottawa Treaty on landmines are examples of global initiatives that blurtheboundariesofnationstates.

Empire in this sense refers to a new global form of sovereignty. Antonio Negri states that this is not the same as saying that the world is dominated by a country like the United States or China; rather, power lies with a “network” of dominant nation-states, supranational institutions (the UN, OPEC, IMF, WTO, G8, NATO, etc.) and major capitalist corporations (Hardt & Negri, 2000; Negri, 2004). Empire is not like imperialism during the era of colonialism. Empire is a new political form that emerged in response to the dynamics of global capitalism.

Chapter Summary

What Is Social Inequality?

Stratification systems are either closed, meaning they allow little change in social position, or open, meaning they allow movement and interaction between the layers. In a caste system, social standing is based on ascribed status or birth. Class systems are open, with achievement playing a role in social position. People fall into classes based on factors like wealth, income, education, and occupation.

Social Inequality and Mobility in Canada

There are three main classes in Canada: the owning class, middle class, and traditional working class. Social mobility describes a shift from one social class to another. While Canada is supposed to be a meritocracy, many factors hinder upward social mobility.

Global Stratification and Inequality

Global stratification compares the wealth, economic stability, status, and power of countries. By comparing income and productivity between nations, researchers can better identify global inequalities.

6.4. Theoretical Perspectives on Social Inequality

Social stratification can be examined from different sociological perspectives — functionalism, critical sociology, and symbolic interactionism. The functionalist perspective states that inequality serves an important function in aligning individual merit and motivation with social position. Critical sociologists observe that stratification promotes inequality, such as between rich business owners and exploited workers. Symbolic interactionists examine stratification from a micro-level perspective. They observe how social standing affects people’s everyday interactions, particularly the tendency to interact with people of like status, and how the concept of “social class” is constructed and maintained through cultural distinctions of education and taste (or cultural capital) and conspicuous consumption.

Key Terms

absolute poverty: A severe deprivation of basic human needs, including food, safe drinking water, sanitation facilities, health, shelter, education and information.

achieved status: A status received through individual effort or merits (eg. occupation, educational level, moral character, etc.).

ascribed status: A status received by virtue of being born into a category or group (eg. hereditary position, gender, race, etc.).

bourgeoisie: In capitalism, the owning class who live from the proceeds of owning or controlling productive property (capital assets like factories and machinery, or capital itself in the form of investments, stocks, and bonds).

caste system: A system in which people are born into a social standing that they will retain their entire lives.

class: A group who shares a common social status based on factors like wealth, income, education, and occupation.

class system: Social standing based on social factors and individual accomplishments.

class traits: The typical behaviours, customs, and norms that define each class, also called class markers.

conspicuous consumption: Buying and using products to make a statement about social standing.

cultural capital: Cultural assets in the form of knowledge, education, and taste that can be transferred intergenerationally.

downward mobility: A lowering of one’s social class.

empire: A new supra-national, global form of sovereignty whose territory is the entire globe.

equality of condition: A situation in which everyone in a society has a similar level of wealth, status, and power.

equality of opportunity: A situation in which everyone in a society has an equal chance to pursue economic or social rewards.

global stratification: A comparison of the wealth, economic stability, status, and power of countries.

globalization: The integration of international trade and finance markets.

income: The money a person earns from work or investments.

intergenerational mobility: A difference in social class between different generations of a family.

intragenerational mobility: A difference in social class between different members of the same generation.

living wage: The income needed to meet a family’s basic needs and enable them to participate in community life.

lumpenproletariat: In capitalism, the underclass of chronically unemployed or irregularly employed who are in and out of the workforce.

means of production: Productive property, including the things used to produce the goods and services needed for survival: tools, technologies, resources, land, workplaces, etc.

meritocracy: An ideal system in which personal effort—or merit—determines social standing.

neoliberalism: A set of policies in which the state reduces its role in providing public services, regulating industry, redistributing wealth, and protecting the commons while advocating the use of free market mechanisms to regulate society.

power: How many people a person must take orders from versus how many people a person can give orders to.

proletariat: Those who seek to establish a sustainable standard of living by maintaining the level of their wages and the level of employment in society.

relative poverty: Living without the minimum amount of income or resources needed to be able to participate in the ordinary living patterns, customs, and activities of a society.

social inequality: The unequal distribution of valued resources, rewards, and positions in a society.

social mobility: The ability to change positions within a social stratification system.

social stratification: A socioeconomic system that divides society’s members into categories ranking from high to low, based on things like wealth, power, and prestige.

socio-economic status (SES): A group’s social position in a hierarchy based on income, education, and occupation.

standard of living: The level of wealth available to acquire material goods and comforts to maintain a particular socioeconomic lifestyle.

status: The degree of honour or prestige one has in the eyes of others.

structural mobility: When societal changes enable a whole group of people to move up or down the class ladder.

upward mobility: An increase — or upward shift — in social class.

wealth: The value of money and assets a person has from, for example, inheritance.

Chapter Quiz

6.1. What Is Social Inequality?

- What factor makes caste systems closed?

- They are run by secretive governments.

- People cannot change their social standings.

- Most have been outlawed.

- They exist only in rural areas.

- What factor makes class systems open?

- They allow for movement between the classes.

- People are more open-minded.

- People are encouraged to socialize within their class.

- They do not have clearly defined layers.

- Which of these systems allows for the most social mobility?

- Caste

- Monarchy

- Endogamy

- Class

6.2. Social Inequality and Mobility in Canada

- Which person best illustrates opportunities for upward social mobility in Canada?

- First-shift factory worker

- First-generation college student

- Firstborn son who inherits the family business

- First-time interviewee who is hired for a job

- Which statement illustrates low status consistency?

- A suburban family lives in a modest ranch home and enjoys a nice vacation each summer.

- A single mother receives welfare and struggles to find adequate employment.

- A college dropout launches an online company that earns millions in its first year.

- A celebrity actress owns homes in three countries.

- Based on meritocracy, a physician’s assistant would _______________ .

- Receive the same pay as all the other physician’s assistants

- Be encouraged to earn a higher degree to seek a better position

- Most likely marry a professional at the same level

- Earn a pay raise for doing excellent work

- In Canada, most people define themselves as _______________.

- Middle class

- Upper class

- Lower class

- No specific class

- Structural mobility occurs when _______________.

- An individual moves up the class ladder.

- An individual moves down the class ladder.

- A large group moves up or down the class ladder due to societal changes.

- A member of a family belongs to a different class than his or her siblings.

- The intergenerational behaviours, customs, education, taste, and norms associated with a class are known as _______________.

- class traits

- power

- prestige

- underclass

- Which of the following scenarios is an example of intergenerational mobility?

- A janitor belongs to the same social class as his grandmother.

- An executive belongs to a different class than her parents.

- An editor shares the same social class as his cousin.

- A lawyer belongs to a different class than her sister.

- Occupational prestige means that jobs are _______________.

- all equal in status

- not equally valued

- assigned to a person for life

- not part of a person’s self-identity

6.3. Global Stratification and Inequality

- Social stratification is a system that ________________.

- Ranks society members into categories

- Destroys competition between society members

- Allows society members to choose their social standing

- Reflects personal choices of society members

- Which graphic concept best illustrates the concept of social stratification?

- Pie chart

- Flag poles

- Planetary movement

- Pyramid

Short Answer

6.1. What Is Social Inequality?

-

Track the social stratification of your family tree. Did the social standing of your parents differ from the social standing of your grandparents and great-grandparents? What social traits were handed down by your forebears? Are there any exogamous marriages in your history? Does your family exhibit status consistencies or inconsistencies?

-

What defines communities that have a low-status consistency? What are the ramifications, both positive and negative, of cultures with low-status consistency? Think of specific examples to support your ideas.

-

Review the concept of stratification. Now choose a group of people you have observed and been a part of — for example, cousins, high school friends, classmates, sport teammates, or coworkers. How does the structure of the social group you chose adhere to the concept of stratification?

6.2. Social Inequality and Mobility in Canada

-

Which social class do you and your family belong to? Are you in a different social class than your grandparents and great-grandparents? Does your class differ from your social standing and, if so, how? What aspects of your societal situation establish you in a social class?

-

What class traits define your peer group? For example, what speech patterns or clothing trends do you and your friends share? What cultural elements, such as taste in music or hobbies, define your peer group? How do you see this set of class traits as different from other classes either above or below yours?

-

Provide examples of class inequality and of status inequality in your community. Are there examples in which class inequality differs from status inequality? What is the significance of these differences?

6.3. Global Stratification and Inequality

-

Why is it important to understand and be aware of global stratification? Make a list of specific issues that are related to global stratification. For inspiration, turn on a news channel or read the newspaper. Next, choose a topic from your list and look at it more closely. Who is affected by this issue? How is the issue specifically related to global stratification?

-

Compare a family that lives in a grass hut in Ethiopia to a Canadian family living in a mobile home in Canada. Assuming both exist at or below the poverty levels established by their country, how are the families’ lifestyles and economic situations similar and how are they different?

Further Research

6.1. What Is Social Inequality?

The New York Times investigated social stratification in their series of articles called “Class Matters.” The online accompaniment to the series includes an interactive graphic called “How Class Works,” which tallies four factors — occupation, education, income, and wealth — and places an individual within a certain class and percentile. What class describes you? Test your class rank on the interactive site: http://www.nytimes.com/packages/html/national/20050515_CLASS_GRAPHIC/index_03.html

6.2. Social Inequality and Mobility in Canada

Mark Ackbar made a documentary about social class and the rise of the corporation called The Corporation. The filmmakers interviewed corporate insiders and critics. The accompanying website is full of information, resource guides, and study guides to the film.: http://thecorporation.com/.

6.3. Global Stratification and Inequality

Nations Online refers to itself as “among other things, a more or less objective guide to the world, a statement for the peaceful, nonviolent coexistence of nations.” The website provides a variety of cultural, financial, historical, and ethnic information on countries and peoples throughout the world: http://www.nationsonline.org/oneworld/first.shtml

References

6. Introduction to Social Inequality in Canada

Bourdieu, P. (1990). The logic of practice. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

CBC Radio. (2010, September 14). Part 3: Former gang members. The Current [Audio file]. Retrieved from http://www.cbc.ca/thecurrent/2010/09/september-14-2010.html.

Rogers, T., & Brehl, R. (2008). Ted Rogers: Relentless. The true story of the man behind Rogers Communications. Toronto, ON: HarperCollins.

6.1. What Is Social Inequality?

Boyd, M. (2008). A socioeconomic scale for Canada: measuring occupational status from the census. Canadian Review of Sociology, 45(1), 51-91.

Kashmeri, Z. (1990, October 13). Segregation deeply embedded in India. The Globe and Mail.

Kerbo, H. (2006). Social stratification and inequality: Class conflict in historical, comparative, and global perspective. Boston, MA: McGraw Hill.

Köhler, N. (2010, November 22). An uncommon princess. Maclean’s. Retrieved from http://www2.macleans.ca/2010/11/22/an-uncommon-princess/.

McKee, V. (1996, June 9). Blue blood and the color of money. The New York Times.

Marquand, R. (2011, April 15). What Kate Middleton’s wedding to Prince William could do for Britain. Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved from http://www.csmonitor.com/World/Europe/2011/0415/What-Kate-Middleton-s-wedding-to-Prince-William-could-do-for-Britain.

6.2. Social Inequality and Mobility in Canada

Abercrombie, N., & Urry, J. (1983). Capital, labour and the middle classes. London, UK: George Allen & Unwin.

Beeghley, L. (2008). The structure of social stratification in the United States. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Corak, M., Curtis, L., & Phipps, S. (2010). Economic mobility, family background, and the well-being of children in the United States and Canada. [PDF] Institute for the Study of Labor. (Discussion paper no. 4814). Bonn, Germany. Retrieved from http://ftp.iza.org/dp4814.pdf.

DeVine, C. (2005). Class in turn-of-the-century novels of Gissing, James, Hardy and Wells. London, UK: Ashgate Publishing Co.

Gilbert, D. (2010). The American class structure in an age of growing inequality. Newbury Park, CA: Pine Forge Press.

Hollett, K. (2015). BC Supreme Court rules homeless have right to public spaces. Pivotlegal.org. Retrieved from http://www.pivotlegal.org/bc_supreme_court_rules_homeless_have_right_to_public_space.

Human Resources and Skills Development Canada. (2010). Average annual percentage wage adjustments. Retrieved from http://www.hrsdc.gc.ca/eng/labour/labour_relations/info_analysis/wages/adjustments/2010/09/quarterly.shtml.

Johnstone, A., & Cooper, T. (2013, May 1). It pays to pay a living wage. CCPA Monitor. Retrieved from https://www.policyalternatives.ca/publications/monitor/it-pays-pay-living-wage.

McArthur, G. (2013, November 23). Assessing the financial affairs of “average guy” Mayor Rob Ford. The Globe and Mail. Retrieved from http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/toronto/assessing-the-financial-affairs-of-average-guy-mayor-rob-ford/article15574327/.

McDonald, D. (2014). Outrageous fortune: Documenting Canada’s wealth gap. [PDF] Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. Retrieved from https://www.policyalternatives.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/publications/National%20Office/2014/04/Outrageous_Fortune.pdf.

McFarland, J. (2011, May 29). Back in the green: CEO pay jumps 13 per cent. The Globe and Mail. Retrieved from http://www.theglobeandmail.com/report-on-business/careers/management/back-in-the-green-ceo-pay-jumps-13-per-cent/article582023/.

Osberg, L. (2008). A quarter century of economic inequality in Canada: 1981-2006. [PDF] Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. Retrieved from http://www.policyalternatives.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/publications/National_Office_Pubs/2008/Quarter_Century_of_Inequality.pdf.

Retail Council of Canada. (2014). Minimum wage by province. RCC: The Voice of Retail. Retrieved from http://www.retailcouncil.org/quickfacts/minimum-wage.

Statistics Canada. (2013, January 28). The daily — high-income trends among Canadian taxfilers, 1982 to 2010. Retrieved from http://www.statcan.gc.ca/daily-quotidien/130128/dq130128a-eng.htm.

Townsend, P. (1979). Poverty in the United Kingdom. London, UK: Penguin.

United Nations. (1995). Chapter 2: Eradication of poverty. The Copenhagen Declaration and Programme of Action, World Summit for Social Development. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/wssd/text-version/agreements/poach2.htm.

Veltmeyer, H. (1986). Canadian class structure. Toronto, ON: Garamond.

Warner, B. (2014). Rob Ford net worth: How much is Rob Ford worth? Celebrity Networth. Retrieved from http://www.celebritynetworth.com/richest-politicians/republicans/rob-ford-net-worth/.

Weber, M. (1969). Class, status and party. In Gerth & Mills (Eds.), Max Weber: Essays in sociology (pp. 180-195). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Williams, R. (1984). Keywords: A vocabulary of culture and society. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. (Original work published 1976).

Yalnizyan, A. (2007, March 1). The rich and the rest of us: The changing face of Canada’s growing gap. [PDF] Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. Retrieved from https://www.policyalternatives.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/publications/National_Office_Pubs/2007/The_Rich_and_the_Rest_of_Us.pdf.

Yalnizyan, A. (2010). The rise of Canada’s richest 1%. [PDF] Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. Retrieved from http://www.policyalternatives.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/publications/National%20Office/2010/12/Richest%201%20Percent.pdf.

6.3. Global Stratification and Inequality

Beck, U. (2000). What is globalization? Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

Campbell, B. (2013). The petro-path not taken: Comparing Norway with Canada and Alberta’s management of petroleum wealth. [PDF] Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. Retrieved from http://www.policyalternatives.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/publications/National%20Office/2013/01/Petro%20Path%20Not%20Taken_0.pdf.

CBC News. (2013, October 19). Former Fed chair Alan Greenspan on his free-market views. CBC. Retrieved from http://www.cbc.ca/news/business/former-fed-chair-alan-greenspan-on-his-free-market-views-1.2287039.

Hardt, M., & Negri, A. (2000). Empire. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Harvey, D. (1989). The condition of postmodernity: An enquiry into the origins of cultural change. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

Harvey, D. (2005). A brief history of neoliberalism. London, UK: Oxford University Press.

Landler, M., & Sanger, D. E. (2009, April 3). World leaders pledge $1.1 trillion for crisis. The New York Times. Retrieved form http://www.nytimes.com/2009/04/03/world/europe/03summit.html.

Marx, K., & Engels, F. (1977). The communist manifesto. In D. McLellan (Ed.), Karl Marx: Selected writings (pp. 221–247). London, UK: Oxford University Press. (Original work published 1848.)

Millennium Project. (2006). Expanding the financial envelope to achieve the goals. Retrieved from http://www.unmillenniumproject.org/reports/costs_benefits2.htm.

Negri, A. (2004). Negri on Negri. New York, NY: Routledge

OECD. (2015, July 7). OECD health statistics 2015. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/health-data.htm.

Rostow, W. W. (1960). The Stages of economic growth: A non-communist manifesto. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

United Nations. (2015). The millennium development goals report [PDF]. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/2015_MDG_Report/pdf/MDG%202015%20rev%20(July%201).pdf.

6.4. Theoretical Perspectives on Social Stratification

Abercrombie, N., & Urry, J. (1983). Capital, labour and the middle classes. London, UK: George Allen & Unwin.

Basketball-reference.com. (2011). 2010–11 Los Angeles Lakers roster and statistics. Retrieved from http://www.basketball-reference.com/teams/LAL/2011.html.

Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction: A social critique of the judgement of taste. New York, NY: Routledge.

Davis, K., & Moore, W. E. (1945). Some principles of stratification. American Sociological Review, 10(2), 242–249. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2085643.

Marx, K. (1848). Manifesto of the Communist Party. Retrieved from http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1848/communist-manifesto/.

Shaienks, D., & Gluszynski, T. (2007). Participation in postsecondary education. Culture, Tourism and the Centre for Education Statistics Research Papers. Statistics Canada. Retrieved from http://www.pisa.gc.ca/eng/participation.shtml.

Statistics Canada. (2013, January 28). The Daily — High-income trends among Canadian taxfilers, 1982 to 2010. Retrieved from http://www.statcan.gc.ca/daily-quotidien/130128/dq130128a-eng.htm.

Tumin, M. M. (1953). Some principles of stratification: A critical analysis. American Sociological Review, 18(4), 387–394.

Veblen, T. (1994). The theory of the leisure class. New York, NY: Dover. (Original work published 1899).

Yalnizyan, A. (2007, March). “The rich and the rest of us: The changing face of Canada’s growing gap.” [PDF] Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. Retrieved from https://www.policyalternatives.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/publications/National_Office_Pubs/2007/The_Rich_and_the_Rest_of_Us.pdf.

Yalnizyan, A. (2010, December). The rise of Canada’s richest 1%. Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. [PDF] Retrieved from http://www.policyalternatives.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/publications/National%20Office/2010/12/Richest%201%20Percent.pdf.

Image Attributions

Figure 6.1

Figure 6.2. Statue of Ted Rogers by Oaktree (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ted_Rogers_Statue_Toronto.JPG) is used under a Free Art License.

Figure 6.6. Downtown Eastside by Wayne Stadler (https://www.flickr.com/photos/waynerd/3081073598/) used under a CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/)

Figure 6.7: Miners in Nanaimo, BC, Image B-03624, Royal BC Museum, BC Archives, is in the public domain (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain)

Figure 6.8. James & Laura Dunsmuir in Italian Garden, CA RRU 2011.025-B-1-11, Royal Roads University Archives, is in the public domain (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain)

Figure 6.11. Charles Dickens by Jeremiah Gurney (http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dickens_Gurney_head.jpg) is in the public domain (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain)

Figure 6._ Karl Marx courtesy of John Mayall (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Portraits_of_Karl_Marx#/media/File:Karl_Marx_coloured.gif) is in the public domain

Figure 6.20. Pierre Trudeau 1975 (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pierre_Trudeau_%281975%29.jpg) used under a CC BY-SA 3.0 license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en)

Figure 6.21. 1964 …Solo and Illya! by James Vaughan (https://www.flickr.com/photos/x-ray_delta_one/4169455648) used under a CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.0/)

Figure 6.22. Towards the Dawn by the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Towards_the_Dawn.jpg) is in the public domain.

Figure 6.23. Imelda Marcos shoes by Vince Lamb (https://www.flickr.com/photos/22320444@N08/4999794433/) used under a CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.0/).

Table 6.2. Share of Aggregate Incomes Received by each Quintile of Families and Unattached Individuals in Osberg (2008) is used under a CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 license (https://www.policyalternatives.ca/terms)

Table 6.3. Gini index of inequality: 1980-2005 in Osberg (2008) is used under a CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 license (https://www.policyalternatives.ca/terms)

Table 6.4. Gini Coefficients of Income Concentration in 27 OECD Countries in Osberg (2008) is used under a CC BY-NC-ND 3.0 license (https://www.policyalternatives.ca/terms)

Long Description

Figure 6.22: Long Description: A family walks up a road towards the rising sun. The sun is labeled “CCF” with the suns rays saying, “Prosperity, justice, democracy, unity, equality, freedom, security.”

Solutions to Chapter Quiz

1 b, | 2 a, | 3 d, | 4 b, | 5 c, | 6 d, | 7 a, | 8 c, | 9 a, | 10 b, | 11 b, |

12 a, | 13 d, | 14 c, | 15 a, | 16 b, | 17 b, | 18 d

[Return to Quiz]