8 Racism and Discrimination

Learning Objectives

8.1. Racialization, Ethnicity, and Minority Groups

- Understand the difference between race and ethnicity.

- Define a majority group (dominant group).

- Define a minority group (subordinate group).

8.2. Stereotypes, Prejudice, and Discrimination

- Explain the difference between stereotypes, prejudice, discrimination, and racism.

- Identify different types of discrimination.

8.3. Intergroup Relations and the Management of Diversity

- Explain different intergroup relations in terms of their relative levels of tolerance.

- Give historical and/or contemporary examples of each type of intergroup relation.

8.4. Racism and Discrimination in Canada

- Compare and contrast the different experiences of various ethnic groups in Canada.

- Apply theories of intergroup relations and race and ethnicity to different subordinate groups.

Introduction

Canada is an increasingly diverse nation with an official policy of multiculturalism. Historically, Canada is a settler society, a society based on colonization and displacement of Indigenous inhabitants. Immigration is a major influence on contemporary population diversity.

In the two decades following World War II, Canada’s immigration policy was explicitly racist. In 1947 Prime Minister Mackenzie King said this in the House of Commons:

There will, I am sure, be general agreement with the view that the people of Canada do not wish, as a result of mass immigration, to make a fundamental alteration in the character of our population. Large-scale immigration from the orient would change the fundamental composition of the Canadian population…. The government, therefore, has no thought of making any change in immigration regulations which would have consequences of the kind. (as cited in Li, 1996, pp. 163-164)

Today this is a completely unacceptable statement. Immigration is now based on a non-racial point system. Canada defines itself as a multicultural nation that promotes and recognizes diversity. This does not mean, however, that Canada’s history of institutional and individual racism has been erased. It doesn’t mean that all conflict in a diverse population has been resolved.

In 1997, the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination criticized the Canadian government for using the term visible minority. The Committee said that distinctions based on race or colour are discriminatory (CBC, 2007). The term combines a diverse group of people into one category whether they have anything in common or not. What does it mean to be a member of a visible minority in Canada? What does it mean to be a member of the non-visible majority? What do these terms mean in practice?

8.1. Racialization, Ethnicity, and Minority Groups

The terms race, ethnicity, and minority group have distinct meanings for sociologists. Race refers to superficial physical (sometimes social) differences, while ethnicity describes shared culture. And minority group describes groups that are subordinate, or lacking power in society. For example, the elderly might be considered a minority group due to diminished status in our society. The World Health Organization’s research on elderly maltreatment shows that 10% of nursing home staff admit to physically abusing an elderly person in the past year, and 40% admit to psychological abuse (2011). As a minority group, the elderly are also subject to economic, social, and workplace discrimination.

Visible minorities are defined by Statistics Canada as “persons, other than Indigenous peoples, who are non-Caucasian in race or non-white in colour” (2013, p. 14).

| Cities | Total Population | Visible Minority Population | Percentage | Top Three Visible Minority Groups |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canada | 32,852,325 | 6,264,755 | 19.1% | South Asian, Chinese, Black |

| Toronto | 5,521,235 | 2,596,420 | 47.0% | South Asian, Chinese, Black |

| Montréal | 3,752,475 | 762,325 | 20.3% | Black, Arab, Latin American |

| Vancouver | 2,280,695 | 1,030,335 | 45.2% | Chinese, South Asian, Filipino |

| Ottawa – Gatineau | 1,215,735 | 234,015 | 19.2% | Black, Arab, Chinese |

| Calgary | 1,199,125 | 337,420 | 28.1% | South Asian, Chinese, Filipino |

| Edmonton | 1,139,585 | 254,990 | 22.4% | South Asian, Chinese, Filipino |

| Winnipeg | 714,635 | 140,770 | 19.7% | Filipino, South Asian, Black |

| Hamilton | 708,175 | 101,600 | 14.3% | South Asian, Black, Chinese |

Racialization

The concept of race has changed across time and cultures, becoming less connected with ancestral ties, and more concerned with superficial physical or social characteristics. In the past, categories of race were invented based on geographic regions, ethnicities, skin colours, and more. However, these early ideas are incorrect: race is not biologically based. Racialization means that race is socially constructed. Certain groups become racialized through a social process that marks them for unequal treatment based on perceived differences.

Consider skin tone, for example: the social construction of race recognizes that the relative darkness or fairness of skin is an evolutionary adaptation to the available sunlight in different regions. In some countries, such as Brazil, class determines racial categorization more than skin colour, for example. People with high levels of melanin (a pigment that determines skin colour) may consider themselves “white” if they enjoy a middle-class lifestyle. On the other hand, someone with low levels of melanin in their skin might be assigned the identity of “Black” if they have little education or money.

Names for racial categories change, also showing that race is a system of social labelling. For example, the category negroid, popular in the 19th century, evolved into the term negro by the 1960s, and then this term was replaced with Black Canadian. The term was intended to celebrate the multiple identities that a Black person might hold, but the term oversimplifies: It lumps together a large variety of ethnic groups. Unlike the United States where the term African American is common, many Black Canadians immigrated from the Caribbean and retain ethnic roots from that area. Culturally they remain distinct from immigrants from sub-Saharan Africa or the descendants of the slaves brought to mainland North America. Some prefer to use the term Afro-Caribbean Canadian for that reason.

The Ontario Human Rights Commission explains that ideas about “race” are socially constructed differences:

based on characteristics such as accent or manner of speech, name, clothing, diet, beliefs and practices, leisure preferences, places of origin and so forth. The process of social construction of race is called racialization: “the process by which societies construct races as real, different and unequal in ways that matter to economic, political and social life” (Racial discrimination, race and racism)

Because race is a social construct, the Commission describes people as racialized person or racialized group instead of the inaccurate racial minority, visible minority, person of colour or non-white (Racial discrimination, race and racism).

In 1978 France made it illegal to collect census data on ethnicity because the data could be used for racist purposes. Davies points out that “this has the side-effect of making systemic racism in the labour market much harder to quantify” (2017).

Research organizations like Statistics Canada and the Conference Board of Canada still use categories such as Black or visible minority in reports. Many sociology studies also use such terms to analyze racism. This book uses the language of those reports to describe obstacles faced by racialized groups in Canada.

What Is Ethnicity?

Ethnicity is a term used to describe shared culture—the practices, values, and beliefs of a group. This might include shared language, religion, and other traditions. Like race, the term ethnicity is imprecise, and its meaning changed over time. And like race, individuals may be identified or self-identify with ethnicities in complex, even contradictory, ways. For example, ethnic groups such as Irish, Italian, Russian, Jewish, and Serbian might all be groups whose members are included in the racialized category white. Conversely, the ethnic group British includes citizens from many racial backgrounds: Black, Afro-Caribbean, white, Asian, etc. These examples illustrate the complexity of these identifying terms. Ethnicity, like race, continues to be an identification method used—whether through the census, affirmative action initiatives, non-discrimination laws, or daily interaction. Not everyone agrees with these labels.

What Are Minority Groups?

Sociologist Louis Wirth defined a minority group as “any group of people who, because of their physical or cultural characteristics, are singled out from others in their society for differential and unequal treatment, and who therefore regard themselves as objects of collective discrimination” (1945). These definitions correspond to the concept that the dominant group as the one with the most power in a society, while subordinate groups are those who lack power. Lack of power is the main characteristic of a minority or subordinate group.

A numerical minority is not a necessarily a characteristic of being a minority group; sometimes larger groups can be considered minority groups due to their lack of power. For example, consider apartheid in South Africa: a numerical majority (the Black inhabitants of the country) were exploited and oppressed by the white minority.

Scapegoat theory suggests that the dominant group will displace their unfocused aggression onto a subordinate group. History shows many examples of the scapegoating of a subordinate group. Adolf Hitler used the Jewish people as scapegoats for Germany’s social and economic problems. In Canada, eastern European immigrants were labelled Bolsheviks and interned during the economic slump after World War I. In the United States, many states made laws to disenfranchise immigrants; these laws were popular because they let the dominant group scapegoat a subordinate group. Many minority groups have been scapegoated for a nation’s—or an individual’s—problems.

8.2. Stereotypes, Prejudice, and Discrimination

Stereotypes

The terms stereotype, prejudice, discrimination, and racism are often used interchangeably. Sociologists define them differently:

- Stereotypes are oversimplified ideas about groups of people

- Prejudice refers to thoughts and feelings about those groups

- Discrimination refers to actions toward them.

- Racism is a type of prejudice that involves set beliefs about a racialized group

Stereotypes are oversimplified ideas about groups of people. Stereotypes can be based on race, ethnicity, age, gender, sexual orientation—almost any characteristic. They may be positive but are often negative (usually toward other groups, such as when members of a dominant group suggest that a subordinate group is stupid or lazy). Whether positive or negative, the stereotype is a false generalization.

Where do stereotypes come from? New stereotypes are rarely created; rather, they are recycled from old stereotypes. They are reused to describe new subordinate groups. For example, many stereotypes currently used to characterize Black people were used earlier in Canadian history to characterize Irish and eastern European immigrants.

Prejudice and Racism

Prejudice refers to beliefs, thoughts, feelings, and attitudes that someone holds about a group. A prejudice is not based on experience; instead, it is a prejudgment. Racism is a type of prejudice that is used to justify the belief that one racialized category is somehow superior or inferior to others. White supremacist groups are examples of racist organizations; their members’ belief in white supremacy has encouraged hate crimes and hate speech for over a century.

Discrimination

While prejudice refers to biased thinking, discrimination consists of actions against a group of people. Discrimination can be based on age, religion, health, sexuality and other indicators. Anti-discrimination laws try to address this social problem.

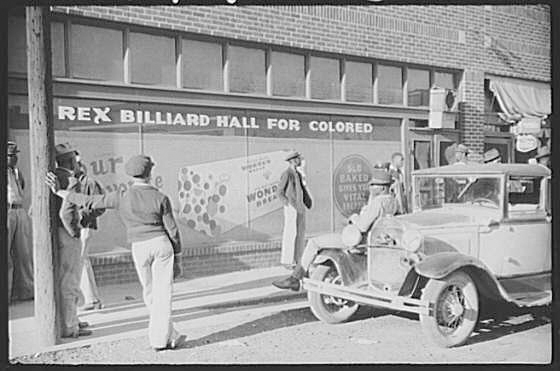

Discrimination based on racialized categories or ethnicity can take many forms, from unfair housing practices to biased hiring systems. Open discrimination has long been part of Canadian history. Discrimination against Jews was typical until the 1950s. McGill University imposed quotas on the admission of Jewish students in 1920, a practice which continued in its medical faculty until the 1960s. The Nova Scotia case of Viola Desmond shows that Canada had also its own version of American Jim Crow laws, which designated “whites only” areas in cinemas, public transportation, workplaces, etc. Both Ontario and Nova Scotia had racially segregated schools. These practices are unacceptable in Canada today.

However, discrimination cannot be erased from our culture just by making laws. Sociologist Émile Durkheim called racism “a social fact,” meaning that it does not require individual action to continue (1895). The reasons are complex and relate to educational, criminal, economic, and political systems.

For example, when a newspaper racializes individuals accused of a crime, it may deepen stereotypes of a minority. Stereotypes of Somali Canadians, for example, were reinforced by news reports of gang-related deaths in Toronto’s social housing projects (Wingrove & Mackrael, 2012). Another example of racist practices is racial steering, in which real estate agents direct home buyers toward or away from certain neighbourhoods based on race. Racist attitudes and beliefs are often more sinister than specific racist practices.

Discrimination can promote a group’s status, such white privilege. While most white people admit that non-white people live with a set of disadvantages, very few white people acknowledge the benefits they receive simply by being white. White privilege refers to the fact that dominant groups often accept their experience as normative (or superior) experience. This is often unconscious racism. Feminist sociologist Peggy McIntosh described several examples of “white privilege.” For instance, white women can easily find makeup that matches their skin tone, and white people can be assured that, most of the time, they will be dealing with authority Images of their own race (1988). Can you think of other examples of white privilege?

Institutional Racism

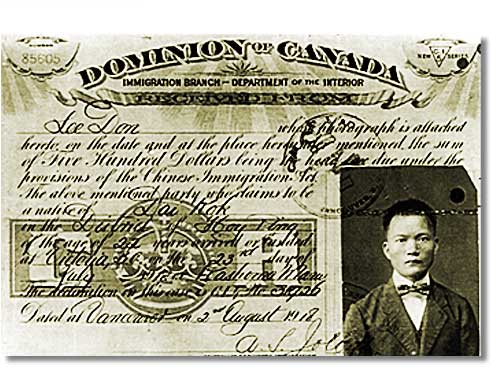

Discrimination also manifests in different ways. In addition to individual discrimination, institutional discrimination or institutional racism exists when a social system embeds disenfranchisement of a group. One example is Canadian immigration policy that imposed head taxes on Chinese immigrants in1886 and 1904.

Institutional racism refers to the way in which racialized distinctions are used to organize the policy and practice of institutions. These distinctions systematically reproduce inequalities along racialized lines. They define what people can and cannot do based on racialized characteristics. It is not necessarily the intention to reproduce inequality. Rather, inequality results from patterns of differential treatment based on racialized or ethnic categorizations of people.

The Indian Act and immigration policy provide clear examples of institutional racism in Canada. Effects of institutional racism can also be observed in the structures that reproduce income inequality for visible minorities and Indigenous Canadians.

An important historical example of institutionalized racism is the residential school system. The residential school system was set up in the 19th century to assimilate Indigenous children into European culture. From 1883 until 1996, over 150,000 Indigenous, Inuit, and Métis children were forcibly separated from their parents and their cultural traditions and sent to residential schools. They usually received substandard education. Many were subject to neglect, disease, and abuse. Many did not see their parents again, and thousands of children died at the schools.

When they did return home, they found it difficult to fit in. They had not learned the skills needed for life on reserves and had also been taught to be ashamed of their cultural heritage. Because the education at the residential schools was often inferior, they also had difficulty fitting into non-Indigenous society.

The residential school system was part of a system of institutional racism because it was based on a distinction between the educational needs of Indigenous and non-Indigenous people. In introducing the policy to the House of Commons in 1883, Public Works Minister Hector Langevin argued, “In order to educate the children properly we must separate them from their families. Some people may say that this is hard but if we want to civilize them we must do that” (as cited in Truth and Reconciliation Commission, 2012, p. 5).

The sad legacy of this “civilizing” mission has been:

- several generations of severely disrupted Indigenous families and communities;

- the loss of Indigenous languages and cultural heritage;

- and the neglect, abuse, and traumatization of thousands of Indigenous children.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission concluded that the residential school system was a systematic assault on Indigenous families, children, and cultures in Canada. Some see the policy and its legacy to cultural genocide (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2012).

While the last of the residential schools closed in 1996, serious problems remain for Indigenous education. Forty percent of Indigenous people aged 20 to 24 have no high school diploma (61% of on-reserve Indigenous people), compared to 13% of non-Indigenous (Congress of Indigenous Peoples, 2010). The impact of generations of children being removed from their homes to underfunded and frequently abusive residential school system has been “joblessness, poverty, family violence, drug and alcohol abuse, family breakdown, sexual abuse, prostitution, homelessness, high rates of imprisonment, and early death” (Truth and Reconciliation Commission, 2012).

Even with the public apology to residential school survivors and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, the federal government continues to refuse basic Indigenous claims to title, self-determination, and control over their lands and resources.

Missing Pages

My name is Shirley Christmas (nee Paul) I was born in Gagetown, New Brunswick, on my grandparent’s farm which my grand mother was the mid-wife in those days. I always jokingly said, she was the first ever to smack me in the butt. I come from a large family consisting of 12 sisters and two brothers, I am the third eldest. I lived in Membertou since I turned 2 years of age.

Today I am about to embark on an emotional journey that took place when I was knee high to a grasshopper at the age of five to the age of eleven. For many years after leaving in 1961, the residential school became my nightmare till it burned to the ground in 1986; then the nightmares stopped but my childhood now lays buried beneath its ashes forever lost.

Where do I begin? The reason why I am so unsure of where I want to start is because it’s a long treacherous road that is not easy to travel; for hidden in the deepest crevasses is a darkened secret that lives within the very depths of my soul that no one knew about except me, God and another person. While growing up I did my best to avoid this path, knowing to well the agonizing pain it caused me. I felt so unloved, unworthy even to my parents and siblings for a very long time.

I began drinking at the age of sixteen in order too drown my sorrows. I became a bitter wicked person who was angry with the world. When I was in a drunken stupor, I cared not who I hurt with my words and lashed out like a wild beast. Before long I had become an alcoholic, the only time I felt no pain was when I was drunk.

During the years of my growth into maturity, I thought for sure that someday I would forget this part of my life and live normal like every one else. I use to think I was the only person carrying this burden, where my soul would suffer in silence from the pain, humiliation and shame. I did what I could to lessen the anguish I held inside.

One day after being on a three-day drunk, I was shown the path I was on. It was my wake-up call to either better my life or stay being a slave to the bottle. It was then I realized that I wasn’t the only one hurting, I was hurting the most precious person in my entire life. I was building a destructive roadway for my two-year-old son, who was standing there in a dirty diaper and a bottle with sour milk in his little hands. I looked around the room saw all the beer bottles laying all over the place some broken and the house reeking of old beer and cigarettes. I shouted to no one but me with tears running down my face I was beginning to feel the shame of being an unfit mother. I said these words that echoed through the house. “What am I doing? How could I do this to my son?” It was then I knew what I had to do to give my child a good life. I have been sober for forty-five years, since that day. It was also the day I closed the door of my thoughts from the days of the Residential School burying it so deep as to never resurface again. Well, so I thought.

Was my life so traumatized as a child between the ages of five and eleven that it became a blank wall? Where did my life go, why was I not remembering when other’s reminiscence their childhood as if it were yesterday? I do remember before I was five like the places where we lived, I remember a time a close friend and I were about three and we had a knack of getting into mischief without trying, it was just a natural occurrence when ever we were together, this still accounts for today.

I remember I was at Jane’s house because my mother was working in town, then Pauline ran across the street to see her mother; Jane and I should have been playing with our dolls, but instead we got into the dye. All I know was Jane’s mother came in and here we were all blue from head to toe plus everything else in the room. There were other times my sisters would bring up incidents of our childhood as they remembered. I tried to visualize but it wasn’t meant to be. When I heard the stories, it seemed unreal like watching a total stranger in my space.

You know the saying, “life is like a book,” well there must be some truth in it if you ask me. Not knowing about one’s childhood is like reading a book with missing pages or looking at pictures with marred images. It leaves you wondering about the missing pieces in the photograph or wondered what really happened in the story. Throughout the years having no childhood memories was forever in the back of my mind. I racked my brain trying to remember what I could, however very few came through, while others were unclear shadows of my past.

Another time a friend took me down memory-lane; while she was speaking about us sitting by the brook with our feet dangling in the water. I looked deep within my head, trying to remember, but I could not recall that day. Why is it she can vividly describe what was happening when we were about six or seven? Why can’t I re-live those days as easily as others? What happened to the missing seven years of my young life?

Not having a childhood did not really hit till my grandchildren were of school age and bringing assignments home to ask grandparents what we remembered about our childhood. Well I’m telling you my whole insides were all mumbo jumbo and I was rendered speechless. I didn’t want to cry in front of my grandchildren or my children, so, I told them I couldn’t remember everything and made things up along the way. Ever since then I tried to avoid talking about a past I didn’t have. It became inevitable to me, that I lost my childhood, it was then I broke down and sobbed my heart out. Each time I thought about it I would cringe in fear and the pain surged through my body filled with anger that no longer could be held within. Eventually I was forced to open a door where there were things I had never wanted resurfacing.

I was a scared little girl of five taken away from home in a big truck with a wooden box as a cover from the elements, in this case it was a chilly September morning. This was where we sat all herded like cattle, it felt like we were in the truck all day because it was dark by the time we stopped. The only person I knew was my big brother Ike, together we traveled to the Shubenacadie Indian Residential School after spending the night in a community close to Orangedale where we boarded a train with lots of other native children. I just wanted to go home and I cried most of the trip not leaving my brother’s side. (This was my brother’s second year) this picture was taken day before by a Mi’kmaq photographer Ray Doucette later known as “Raytel Studio’s”It was dark and cold when we arrived at the Shubenacadie train station. After departing from the train, we were separated by people in long dresses and funny hats, who spoke in stern voices. Next thing you know I was ripped from my brother’s side and placed in a row with other girls my age group. I felt the sting of a slap on my face as the nun told me to stop crying now. Then we started walking the long trek to the school on the hill. On our arrival to the school we were taken in a large bathroom where we were told to remove our clothing and put on long night-dresses. Then we were taken to another huge room where we were lined up and had my pony-tails chopped off. I was given a number 16 that would remain with me during the duration of my seven years at the school. I never saw my brother again till we were put back on the train in June to return home. The sad part was I didn’t know him after our first year in the residential school. When we were home for the summer, we got to know each other, but in September we were once again separated.

When I was six and a half, I was taken to the office of the head priest, he was a massive man in a black robe with giant crosses dangling from his attire. I was molested many times since that night. I believe it was that night that I blocked my childhood, the only memories were the bad things that destroyed the little girl in me, when I was told never to tell anyone or I will go straight to hell because God don’t like liars. When I was eight, I was raped by this beast. For many, many years I carried that guilt knowing if I spoke of this sin, I would surely die and go to hell. In 2014, some 58 years later, I finally had the courage to speak of my story, but not without the pain and fear as if it just happened. Finally, the little girl hidden inside me, was at long last set free.Over the past few weeks I struggled within the depths of my spirit and tried to find that connection missing from my story of life. Surely there must have been some happy moments in that god-forsaken place. How will the story end without those missing years of my childhood? These should have been the most creative, adventurous and happy times that I should have experienced while growing up. Yet they were excluded from my story, it became the missing pages of my youth. Today I feel at a loss, because I have no happy memories to share with my children or grandchildren about my younger days. I lost my childhood at the Residential School so many decades ago. What could be more devastating than that?

Personal reflection by Shirley Christmas.

Income Inequality among Racialized Canadians

Income inequality for racialized Canadians also shows the effects of institutional racism. Statistics Canada, the Conference Board of Canada and other research organizations regularly publish statistical reports demonstrating the systemic nature of this income inequality.

The median income of Indigenous people in Canada was 30% less than non-Indigenous people in 2006 (Wilson & Macdonald, 2010). Rates of child poverty (using Statistics Canada’s after-tax low-income measure) for Indigenous people in 2006 were at 40%, while rates for non-Indigenous, non-racialized, non-immigrant children were 12% (Macdonald & Wilson, 2013).

Although labour participation rates are similar for racialized and non-racialized Canadians, unemployment for racialized men and women is much higher. Income levels for racialized Canadians are much lower than for non-racialized Canadians (Block and Galabuzi, 2011). These substantial, statistically significant differences between racialized and non-racialized Canadians indicate that economic institutions in Canada are based on racialized differences in the workforce rather than individual qualities of workers or even individual acts of prejudice by employers.

| Generation | Racialized | Non-racialized | Differential (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | |

| 1st Generation | $45,388 | $32,165 | $66,078 | $39,264 | 68.7% | 81.9% |

| 2nd Generation | $57,237 | $42,804 | $75,729 | $46,391 | 75.6% | 92.3% |

| 3rd or more Generation | $66,137 | $44,460 | $70,962 | $44,810 | 93.2% | 99.2% |

Source: Statistics Canada – 2006 Census. Catalogue Number 97-563-XCB2006060

8.3. Intergroup Relations and the Management of Diversity

Western societies have used different strategies for the management of diversity. A strategy for the management of diversity refers to methods used to resolve conflicts, or potential conflicts, between groups that arise based on perceived differences. The solutions proposed for intergroup relations vary and have evolved. The most tolerant form of intergroup relations is multiculturalism, in which cultural distinctions are made between groups, but the groups are regarded to have equal standing in society. At the other end of the continuum are assimilation, expulsion, and even genocide—stark examples of intolerant intergroup relations.

Genocide

Genocide, the deliberate annihilation of a targeted (usually subordinate) group, is the most toxic intergroup relationship. Genocide has included both the intent to exterminate a group and the function of exterminating of a group, intentional or not.

Possibly the most well-known case of genocide is Hitler’s attempt to exterminate the Jewish people in the first part of the 20th century. Also known as the Holocaust, the explicit goal of Hitler’s “Final Solution” was the eradication of European Jews, as well as other minority groups such as Catholics, people with disabilities, Roma, Jehovah Witnesses, communists and homosexuals. With forced emigration, concentration camps, and mass executions in gas chambers, Hitler’s Nazi regime was responsible for the deaths of 12 million people, including at least 6 million Jews. Hitler’s intent was clear, and the high Jewish death toll certainly indicates that Hitler and his regime committed genocide. But how do we understand genocide that is not so open and deliberate?

During the European colonization of North America, historians estimate that Indigenous populations dropped from approximately 12 million people in the year 1500 to barely 237,000 by the year 1900 (Lewy, 2004). European settlers forced Indigenous people off their own lands, often causing thousands of deaths in forced removals. The Cherokee or Potawatomi Trail of Tears in the United States is one example of forced removal. Settlers also enslaved Indigenous people or forced them to give up their religious and cultural practices.

But the major cause of Indigenous death was the introduction of European diseases, with Indigenous people’s lack of immunity to these foreign diseases. Smallpox, diphtheria, and measles spread rapidly among North American Indigenous peoples, who had no prior exposure to the diseases and therefore no ability to fight them. Some argue that the spread of disease was an unintended effect of settlers, while others believe it was intentional, with rumours of smallpox-infected blankets being distributed as “gifts” to Indigenous communities.

Newfoundland’s Beothuk people became extinct from a variety of factors caused by European contact, including isolation from natural resources needed to sustain their traditional way of life. Shanawdithit, the last known living member of the Beothuk people, died of tuberculosis in St. John’s, Newfoundland on June 6, 1829.

Genocide is not a just a historical concept. Recently, ethnic and geographic conflicts in the Darfur region of Sudan led to hundreds of thousands of deaths, for example. Because of land conflict, the Sudanese government and militias led a campaign of killing, forced displacement, and systematic rape of Darfuri people. A treaty was signed in 2011. There are many examples of 20th and 21st century genocide around the world. Refugees from genocide often live in camps and apply to move to countries like Canada.

Expulsion

Expulsion refers to a dominant group forcing a subordinate group to leave a certain area or country. As seen in the examples of the Beothuk and the Holocaust, expulsion can be a factor in genocide. However, it can also stand on its own as a destructive group interaction. The Great Expulsion of the French-speaking Acadians from Nova Scotia by the British beginning in 1755 is the most notorious case of the use of expulsion to manage diversity in Canada. The British conquest of Acadia (which included contemporary Nova Scotia and parts of New Brunswick, Quebec, and Maine) in 1710 created the problem of what to do with the French colonists who had been living there for 80 years. In the end, approximately three-quarters of the Acadian population were rounded up by British soldiers and loaded onto boats without regard for keeping families together. Many of them ended up in Spanish Louisiana where they formed the basis of contemporary Cajun culture.

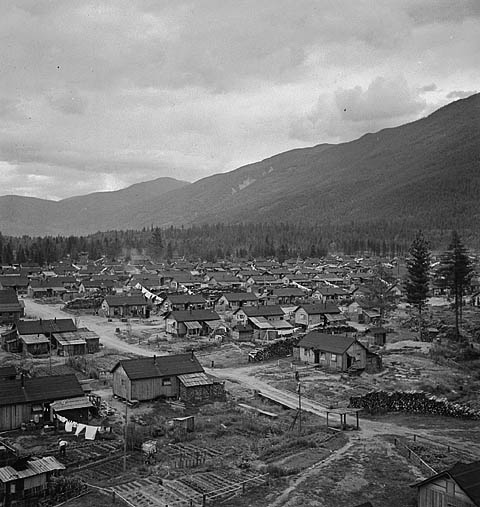

On the West Coast, the War Measures Act was used in 1942 to designate Japanese Canadians as enemy aliens. They were interned in camps. Their property and possessions were sold to pay for their forced removal and internment. David Suzuki ‘s family, for example, was interned in British Columbia from early during the Second World War until after the war ended in 1945. His father was sent to a labour camp and the family business sold, even though they were second- and third generation Canadians. Over 22,000 Japanese Canadians (14,000 of whom were born in Canada) were held in these camps between 1941 and 1949, even though the RCMP and the Department of National Defence reported there was no evidence of collusion or espionage. In fact, many Japanese Canadians demonstrated their loyalty to Canada by serving in the Canadian military during the war.

This was the largest mass movement of people in Canadian history. At the end of World War II, Japanese Canadians were forced to settle east of the Rocky Mountains or face deportation to Japan. This ban only ended after 1949, four years after the war’s end. In 1988, Prime Minister Brian Mulroney issued a formal apology for this expulsion, and compensation of $21,000 was paid to each surviving internee.

Segregation

Segregation refers to the physical separation of two groups, particularly in residence, but also in workplace and social functions. Segregation can be de jure segregation (segregation that is enforced by law) and de facto segregation (segregation that occurs without laws but because of other factors). A stark example of de jure segregation is the apartheid movement of South Africa, which existed from 1948 to 1994. Under apartheid, Black South Africans were stripped of their civil rights and forcibly relocated to areas that segregated them physically from their white compatriots. Only after decades of degradation, violent uprisings, and international advocacy was apartheid finally abolished.

De jure segregation occurred in the United States for many years after the Civil War. During this time, many former Confederate states passed “Jim Crow” laws that required segregated facilities for Blacks and whites. These laws were codified in 1896’s landmark Supreme Court case Plessey v. Ferguson, which stated that “separate but equal” facilities were constitutional. For the next five decades, Blacks were subjected to legalized discrimination, forced to live, work, and go to school in separate—but unequal—facilities. It wasn’t until 1954 and the Brown v. Board of Education case that the Supreme Court declared that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal,” thus ending de jure segregation in the United States.

De jure segregation was also a factor in Canada’s development. Although slavery ended in Canada in 1834, when Britain abolished slavery throughout the empire, the approximately 60,000 Blacks who arrived with the British Empire Loyalists following the American Revolution and through the “Underground Railroad” were subject to discrimination and differential treatment. Legislation in Ontario and Nova Scotia created racially segregated schools, while de facto segregation of Blacks occurred in the workplace, restaurants, hotels, theatres, and swimming pools.

Similarly, segregating laws were passed in British Columbia, Saskatchewan, and Ontario preventing Chinese- and Japanese-owned restaurants and laundries from hiring white women out of concern that the women would be corrupted (Mosher, 1998). The reserve system created through the treaty process with First Nations peoples is also a form of de jure segregation. De jure segregation (except for the reserve system) was largely eliminated in Canada by the 1950s and 1960s.

De facto segregation, however, cannot be abolished by courts. Segregation has existed throughout Canada, with different racial or ethnic groups often segregated by neighbourhood. Various Chinatowns or Japantowns developed in Canadian cities in the 19th and 20th centuries. The community of Africville was a residentially and socially segregated Black enclave in Halifax established by escaped American slaves. Some urban neighbourhoods like Richmond, Surrey, and Markham are home to high concentrations of Chinese and South Asians.

Assimilation

Assimilation describes the process by which a minority individual or group gives up its own identity by taking on the characteristics of the dominant culture. In Canada, assimilation was government policy with the Indian Act. The Indian Act attempted to Europeanize the Indigenous population. Assimilation was also the policy for absorbing immigrants from different lands.

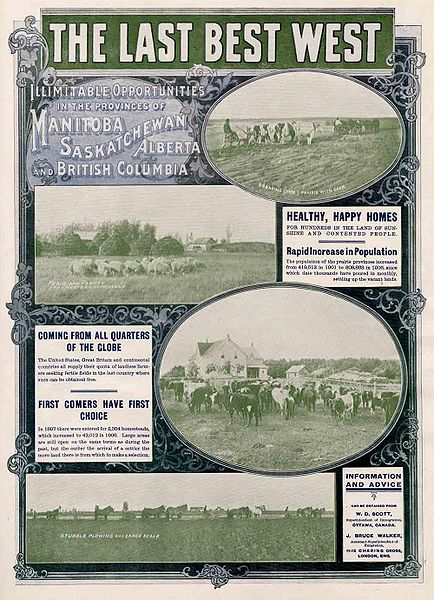

Canada is a settler nation. Except for Indigenous Canadians, all Canadians have immigrant ancestors. In the 20th century, there were three waves of immigration to Canada (Li, 1996).

- During the wheat boom from 1900 to the beginning of World War I, Canada recruited almost 3 million settlers from various parts of Europe, although many subsequently emigrated to the United States.

- For the two decades following World War II, another 3 million immigrants arrived (96% from Europe between 1946 and 1954, and 83% from Europe between1954 and 1967).

- The third wave of immigration following the change of the race-based immigration policy saw increasingly larger proportions of immigrants from non-European countries.

Most immigrants are eventually absorbed into Canadian culture, although sometimes after facing extended periods of prejudice and discrimination. Assimilation means the loss of the minority group’s cultural identity as the people in that group become absorbed into the dominant culture, while there is minimal to no impact on the majority group’s cultural identity.

Some assimilated groups may keep only symbolic gestures of their original ethnicity. For instance, many Irish Canadians may celebrate Saint Patrick’s Day, many Hindu Canadians enjoy the Diwali festival, and many Chinese Canadians may celebrate Chinese New Year. However, for the rest of the year, other aspects of their originating culture may be forgotten.

Assimilation is opposite to the “cultural mosaic” model understood by Canadian multiculturalism; rather than maintaining their own cultural flavour, subordinate cultures give up their own traditions to conform to their new environment. Cultural differences are erased. The American “melting pot” model is like assimilation, although ideally the “melting pot” sees the combination of cultures resulting in a new culture entirely.

Sociologists measure the degree to which immigrants have assimilated to a new culture with four benchmarks:

- socioeconomic status

- spatial concentration

- language assimilation and

- intermarriage.

Discrimination can make assimilation difficult for new immigrants who wish to assimilate. Language assimilation can be a huge barrier, limiting employment and educational options and therefore limiting socioeconomic status.

Multiculturalism

In the government document, Multiculturalism: Being Canadian, multiculturalism is defined as “the recognition of the cultural and racial diversity of Canada and of the equality of Canadians of all origins” (as cited in Day, 2000, 6).

Multiculturalism is represented in Canada by the metaphor of the mosaic: This suggests that in a multicultural society each ethnic or racial group preserves its unique cultural traits while contributing to national unity. Each culture is equally important within the mosaic. Each culture retains its own identity and yet adds to the colour of the whole. Multiculturalism is characterized by mutual respect by all cultures, both dominant and subordinate, creating a polyethnic environment of mutual acceptance.

Canada was the first country to adopt an official multicultural policy. In 1971, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau implemented both a policy of official bilingualism (both French and English would be the languages of the state) and a policy of multiculturalism. The multicultural policy was designed to assist the different cultural groups in Canada to preserve their heritage, overcome cultural barriers to participation in Canadian society, and exchange with other cultural groups to contribute to national unity (Ujimoto, 2000). The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms obliges Canadian law and federal institutions to operate “in a manner consistent with the preservation and enhancement of the multicultural heritage of Canadians” (as cited in Li, 1996, p. 132).

Constitutional democracies like Canada are typically based on the protection of individual rights, but multiculturalism implies that the protection of cultural difference also depends on protecting group-specific rights (i.e., rights conferred on individuals by their membership in a group).

In Canadian multicultural policy, no culture takes precedence over any other, at least not official. All Canadians are recognized as “full and equal participants in Canadian society” (the Canadian Multiculturalism Act of 1988). However, in practice, there has been conflict.

Whether Sikhs in the RCMP should be allowed to wear dastaar while in uniform was an early example. Although it seems trivial today, in 1990 many felt that the right of Sikhs to maintain their religious practice undermined a core tradition of both the police force and Canada. The case became a symbol of a deeper fear about multiculturalism: that it would foster a dangerous fragmentation of fragile Canadian unity. New non-European immigrants were seen by some as too different and accommodation too disruptive to “Canadian” values and practices. Of course, similar claims about the unassimilable differences of immigrants from Ireland, Eastern Europe, and southern Europe were made in earlier waves of immigration.

While Canadians accept diversity—the most accepting of all OECD countries in 2011 according to the Gallup World Poll (Conference Board of Canada, 2013)—issues around multiculturalism bring up the problem of ethical relativism. Ethical relativism is the idea that all cultures and all cultural practices have equal value. In a fully multicultural society, what principles can resolve issues where different cultural beliefs or practices clash?

8.4. Racism and Discrimination in Canada

When colonists came to the New World, they found a land that did not need “discovering” since it was already occupied. While the first wave of immigrants came from western Europe, eventually the bulk of people entering North America were from northern Europe, then eastern Europe, then Latin America and Asia. There was also the forced immigration of African slaves. Most groups underwent a period in which they were relegated to the bottom of the social hierarchy before they managed to achieve social mobility.

Today, our society is multicultural, although the extent to which this multiculturality is embraced varies. The sections below describe how several groups became part of Canadian society, discuss the history of intergroup relations for each group, and assess each group’s status today.

Indigenous Canadians

The only non-immigrant ethnic group in Canada, Aboriginal Canadians were once a large population, but by 2011 they made up only 4.3% of the Canadian populace (Statistics Canada, 2013).

Making Connections: Social Policy and Debate

Sports Teams with Indigenous Names

Team names like Eskimos, Indians, Warriors, Braves, and even Savages and Redskins are common. These names came from historical stereotypes of Indigenous people.

Speaking about the Edmonton Eskimos football team, Natan Obed of Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (the national Inuit organization) argues that the term “Eskimo” is derogatory and represents a legacy of colonialism and disrespect. “If I was called an Eskimo or introduced as an Eskimo by anyone else, I would be offended by that…. It is something that was acceptable at one time but now just isn’t…. It’s time for the team to change its name. And it’s time also for all sports teams to change their names if they continue to use Indigenous people as their mascots” (CBC, 2015).

Since the civil rights movement of the 1960s, the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) ampaigned against the use of mascots, asserting that the “warrior savage myth … reinforces the racist view that Indians are uncivilized and uneducated, and it has been used to justify policies of forced assimilation and destruction of Indian culture” (NCAI Resolution #TUL-05-087, 2005). The campaign has had only limited success. While some teams changed their names, hundreds of professional, college, and school teams still have names derived from stereotypes. Another group, American Indian Cultural Support (AICS) is especially concerned with such names at K–12 schools, grades where children should be gaining a fuller and more realistic understanding of Indigenous people than such stereotypes supply (2005).

What do you think about such names? Should they be allowed or banned? What argument would a symbolic interactionist make on this topic?

How and Why They Came

The earliest humans in Canada arrived millennia before European immigrants. Dates of the migration are debated with estimates ranging from between 45,000 and 12,000 BCE. It is thought that people migrated to this new land from Asia in search of big game to hunt, which they found in huge herds of grazing herbivores in the Americas. Over the centuries and then the millennia, Indigenous cultures blossomed into an intricate web of hundreds of interconnected groups, each with its own customs, traditions, languages, and religions.

History of Intergroup Relations

Indigenous cultures prior to European settlement are referred to as pre-contact or pre-Columbian. Pre-Columbian means prior to the 1492 accidental arrival of Christopher Columbus. Mistakenly believing that he had landed in the East Indies, Columbus called the Indigenous people Indians: a name that persisted for centuries despite being a mistake. That mistake lumped together over 500 distinct groups, all with their own languages and traditions.

The history of intergroup relations between European settlers and Indigenous peoples is brutal. As discussed in the section on genocide, European colonies nearly destroy the Indigenous population. And although Indigenous people’s lack of immunity to European diseases caused the most deaths, overt mistreatment by Europeans was equally devastating.

The history of Indigenous relations with Europeans in Canada since the 16th century can be described in four stages (Patterson, 1972).

- In the first stage, the relationship was largely mutually beneficial and profitable as the Europeans relied on Indigenous groups for knowledge, food, and supplies. Indigenous groups traded for European technologies.

- In the second stage, however, Indigenous people were increasingly drawn into the European-centred economy, coming to rely on fur trading for their livelihood rather than their own indigenous economic activity. This resulted in diminishing autonomy and increasing subjugation economically, militarily, politically, and religiously.

- In the third stage, the reserve system was established, clearing the way for full-scale European colonization, resource exploitation, agriculture, and settlement. If Indigenous people tried to retain their stewardship of the land, Europeans fought them off with more powerful weapons. A key element is the Indigenous view of land and land ownership. Most First Nations cultures considered the Earth a living entity whose resources they could respectfully steward; the concepts of land ownership and conquest did not exist in most Indigenous societies.

- The last stage of the relationship developed after World War II, when Indigenous Canadians began to mobilize politically to challenge oppressive conditions and forced assimilation. In this stage, Indigenous people developed political organizations and turned to the courts to fight for treaty rights and self-government.

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 was a turning point in Indigenous-European relations. The Proclamation established British rule over former French colonies, and set aside lands for First Nations peoples. It legally established that First Nations had sovereign rights to their territory. Although these were often disputed, challenged, or ignored by colonists, land speculators, and subsequent governments, these rights became the basis of contemporary treaty rights and negotiations.

The Indian Act of 1876 was another turning point. The Act attempted to codify and formalize the provisions of the Royal Proclamation and all other accumulated acts of government. The Indian Act was, however, a paternalistic “civilizing policy.” The care of the Indigenous population was placed under the control of the federal government until they could be assimilated into European culture.

Discrimination against Indigenous Canadians was institutionalized. As the deputy superintendent of Indian Affairs said in 1920, “Our objective is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic and there is no Indian question, and no Indian Department” (as cited in Leslie, 1978, p. 114). The Indian Act controlled everything in Indigenous life from who could be defined as an Indian, to the reserve and band council system, to the types of Indigenous activities that would no longer be permitted (potlatch and ceremonial dancing, for example).

Some of the most damaging provisions of the Indian Act and its amendments were:

- The prohibition against owning, acquiring, or “pre-empting” land

- The dismantling of traditional institutions of Indigenous government and the banning of ceremonial practices

- The imposition of the band council system, which was foreign to Indigenous tradition and powerless to make meaningful decisions without approval of the Department of Indian Affairs

- Denial of the power to allocate funds and resources

- The prohibition against hiring lawyers or seeking legal redress in pursuing land claims

- The denial of the right to vote municipally (until 1948), provincially (until 1949), and federally (until 1960) (Mathias & Yabsley, 1991)

Establishment of residential schools in the late 19th century further damaged Indigenous culture. These schools, run by Christian missionaries and the Canadian government, attempted to “civilize” Indigenous Canadian children and assimilate them into European society. The residential schools were located off-reserve to ensure that children were separated from their families and culture. Schools forced children to cut their hair, speak English or French, and practise Christianity. Education in the schools was usually substandard. Physical and sexual abuses were common; only in 1996 did the last of the residential schools close. In 2008 Prime Minister Stephen Harper apologized for residential schools on behalf of the Canadian government. Many of the problems that Indigenous Canadians face today result from almost a century of traumatizing mistreatment at these residential schools.

Current Status

In the 1960s, First Nations began to mobilize politically and intensify their demands for Indigenous rights. The Liberal government’s 1969 White Paper became a focus of Indigenous protest because it proposed to eliminate the Indian Act, the Department of Indian Affairs, and the concept of Indigenous rights altogether. First Nations people would be treated just like everyone else, as if the sovereign treaties and centuries of oppression had not occurred. Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau declared, “No society can be built on historical might-have-beens” (as cited in Weaver, 1981, p. 55).

By the time of the repatriation of the Constitution in 1982, the government’s position reversed, and the status of Indians, Inuit, and Métis were recognized, as were existing Indigenous and treaty rights.

However, Indigenous people still suffer the effects of centuries of discrimination. The income of Indigenous people in Canada is far lower than that of non-Indigenous people, and rates of child poverty are much greater. Even though the last residential school closed in 1996, many Indigenous people still face obstacles to high school completion Long-term poverty, inadequate education resources, cultural dislocation, and high rates of unemployment create obstacles for Indigenous Canadians.

Black Canadians

As discussed in the section on racialization, the term Black Canadian is often preferred to African Canadian. Many Canadians have roots in the Caribbean rather than roots among African slaves from the United States. They see themselves ethnically as Caribbean Canadians. Some recent immigrants from Africa may feel that they have more of a claim to the term African Canadian than those who are many generations removed from ancestors who originally came to this country.

Assumed commonality of the category Black Canadians is a function of racism. The Ontario Human Rights Commission describes people as “racialized person” or “racialized group” instead of the more outdated and inaccurate terms. The section below sometimes contains terminology from studies using older labels.

How and Why They Came

The French in the 17th century brought some African slaves to Canada. At least 6 of the 16 legislators in English Upper Canada owned slaves (Mosher, 1998). The economic conditions in Canada did not encourage slavery, so the practice was not widespread. Nevertheless, it was not until 1834 that slavery was banned throughout the British Empire, including Canada.

Canada became the destination of the Underground Railroad, a secret network organized to transport escaped slaves to freedom. Between the American Revolution in 1776 and the end of the American Civil War in 1865, Canada received approximately 60,000 runaway slaves and Black Empire Loyalists from the United States. Around 10% of the Loyalists who came to Canada after the American Revolution were Black Loyalists (Walker, 1980). They were usually granted land much inferior to Loyalists of European heritage. Many returned to the United States after the Civil War, and by 1911 only about 17,000 remained in Canada (Mosher, 1998).

After immigration policy changes in the late 1960s, more people from the Caribbean immigrated to Canada. Before 1971, The category Black Canadian described less than 1% of the population (Li, 1996). In the 2011 census, 2.9% of the population and 15.1% of all visible minorities were described as Black (Statistics Canada, 2013). People with Caribbean origins make up the largest proportion, with nearly 40% having Jamaican heritage and 32% identifying heritage elsewhere in the Caribbean (Statistics Canada, 2007).

More recently, Somalis from Africa immigrated to Canada because of war. They represent the largest African immigrant group ever to come to Canada in such a short time (Abdulle, 1999).

History of Intergroup Relations

Although slavery became in illegal in Canada in 1834, informal practices of segregation lead to discrimination throughout the 19th century. For example, while Blacks could vote and sit on juries, these rights were frequently denied. Ontario (outside of Toronto) and Nova Scotia legally segregated schools along racialized lines. Those laws remained until 1965 in Ontario and 1983 in Nova Scotia (Black History Canada, 2014).

Sometimes neighourhoods were also segregated (Mosher 1998). Some racialized neighbourhoods were labeled as slums by nonresidents and destroyed. In the 1960s, for example, Halifax city councilors voted to relocate residents of the historic community of Africville as part of “urban renewal.” Africville was bulldozed between 1965 and 1970 without meaningful consultation with Africville residents. The NFB features a free online documentary about the community. In 2010, the government of Nova Scotia apologized to the Africville residents.

Occupational choice was also restricted for Black Canadians in the first half of the 20th century. Employment was often limited to domestic work or railroad porters. For example, the father of Oscar Peterson, the famous jazz pianist, was a Canadian Pacific railroad porter in Montreal, while his mother was employed as a domestic worker (Library and Archives Canada, 2001). For most of the 20th century, Black Canadians were mostly employed in low-pay service jobs or as unskilled labour.

Current Status

Although formal discrimination is illegal, true equality does not yet exist. The 2006 census shows that Black Canadians earned 75.6 cents for every dollar a white worker earned in Canada, or $9,101 less per year. In 2006, 24% of Black individuals in families and 54% of single Black individuals lived in poverty (compared to 6.4% of individuals in white families and approximately 26% of single white individuals) (Block & Galabuzi, 2011).

In addition, Blacks are subject to greater degrees of racial profiling than other groups. Racial profiling refers to the practice of selecting specific racialized groups for greater levels of criminal justice surveillance. Despite police denials, Wortley and Tanner’s study confirms that drivers perceived by Toronto police as Black are more frequently stopped, questioned, and searched by the police for “driving while being Black” violations than other groups (2004).

Asian Canadians

Asian Canadians represent a great diversity of cultures and backgrounds. Asian immigrants arrived in Canada in waves, at different times, and for different reasons. The experience of a Japanese Canadian whose family has been in Canada for five generations will be different from a Laotian Canadian who has only been in Canada for a few years. This section discusses some of the experience of Chinese, Japanese, and South Asian immigrants.

How and Why They Came

The first Asian immigrants to Canada in the mid-19th century were Chinese. These immigrants were mostly men who wanted to work to support their families in China. Their first destination was the Fraser Canyon for the 1858 gold rush. Many of these Chinese came north from California. The second major wave of Chinese immigration arrived for the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway when contractors recruited thousands of workers from Taiwan and China. Chinese labourers were paid approximately a third of what white, Black, and Indigenous workers were paid. Chinese labourers were used to complete the most difficult sections of track, living under squalid and dangerous conditions: More than 600 Chinese workers died during the construction. Chinese men also engaged in other manual labour like mining, laundry, cooking, canning, and agricultural work. The work was grueling and underpaid, but like many immigrants they persevered (Chan, 2013).

The first wave of Japanese immigrants in 1887 were, like the first Chinese immigrants, mostly men. They came from fishing and farming backgrounds in the southern Japanese islands. They settled in Japantowns in Victoria and Vancouver, as well as in the Fraser Valley and small towns along the Pacific coast where they worked mostly in fishing, farming, and logging. Like the Chinese settlers, they were paid much less than workers from European backgrounds and were usually hired for menial labour or heavy agricultural work. With restrictions imposed on the immigration of Japanese men after 1907, most of the early Japanese immigrants after 1907 were women, either the wives or betrothed of Japanese immigrants (Sunahara & Oikawa, 2011).

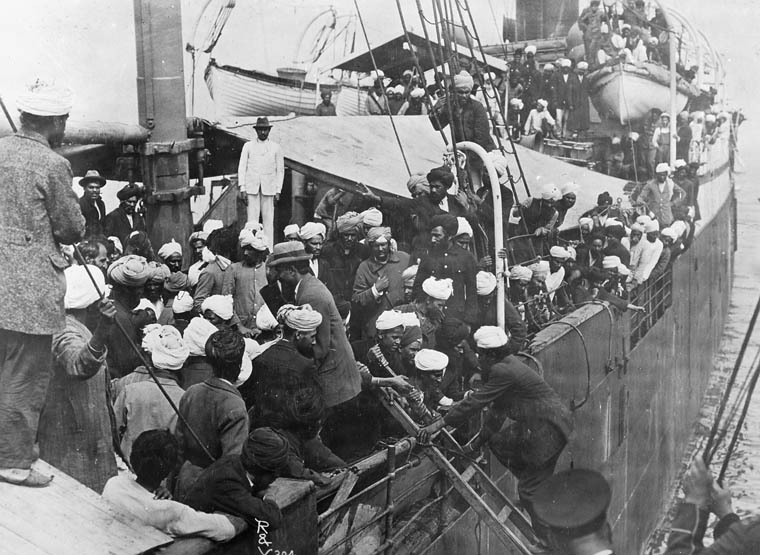

South Asians refer to a diverse group of people with different ethnic backgrounds in India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka. The first South Asians in Canada were Sikhs from the Punjab region of India. The first group of Sikhs arrived in Vancouver in 1904 from Hong Kong, attracted by stories of high wages from British Indian troops who had travelled through Canada (Buchignani, 2010). They were encouraged by Hong Kong–based agents of the Canadian Pacific Railway who had seen travel on their passenger liners plummet with the head tax imposed on Chinese immigration.

Most of the first Sikhs in Canada arrived via Hong Kong or Malaysia, where the British had typically employed them as policemen, watchmen, and caretakers. They were originally from rural areas of Punjab and mortgaged their properties for passage in exchange for the prospect of sending money home. Many arrived in Canada unable to speak English but eventually found employment in mills, factories, the railway, and Okanagan orchards (Johnston, 1989). By 1908 there were over 5,000 South Asians in British Columbia, 90% of them Sikh. (Buchignani, 2010).

History of Intergroup Relations

Asian Canadians were subject to particularly harsh racism in the 19th and 20th centuries. The 1902 Royal Commission on Chinese and Japanese Immigration declared that the Japanese and Chinese were “unfit for full citizenship. They are so nearly allied to a servile class that they are obnoxious to a free community and dangerous to the state” (CBC, 2001).

The right of Asians to vote, own property, and seek employment, and their ability to immigrate and integrate into Canadian society were severely restricted. This disenfranchisement prevented these groups from having access to political office, jury duty, the professions like law, civil service jobs, underground mining jobs, and labour on public works–these all required being on provincial voters’ lists. Voting rights were only returned to Chinese and South Asian Canadians in 1947 and to Japanese Canadians in 1949, whereas immigration restrictions were not removed until the 1960s.

The imposition of “head taxes” of $50 in 1885 and $500 in 1903 were attempts to restrict Chinese immigration. The Chinese Head Tax and Exclusion Act included discriminatory laws that marked the Chinese as unwanted immigrants to Canada from 1885 to 1947.

For similar reasons, the immigration of Japanese men was restricted to 400 a year after 1907, and further reduced to 150 individuals a year after 1928. Their success in the fishing industry led the federal fisheries department to reduce Japanese trolling licenses by one-third in 1922. They, like the Chinese, were also subject to “yellow peril” hysteria. When the Japanese, many veterans of the Russo-Japanese war of 1905, successfully defended their community against white supremacist mobs in the 1907 anti-Asian riots in Vancouver, they were accused of smuggling a secret army into Canada (Sunahara & Oikawa, 2011). An even uglier action was the establishment of Japanese internment camps of World War II, discussed earlier as an illustration of expulsion.

Of the three groups, South Asians were the most recent to arrive. However, by 1908 the large number of arrivals led to the imposition of immigration restrictions. South Asians were British subjects, so restrictions took a more devious form, however. Immigrants from South Asia were obliged to possess at least $200 on arrival (very challenging considering that in British India they might be able to earn 10 to 20 cents a day), and they had to arrive in Canada by continuous passage from India. The government then put pressure on steamship companies not to sell direct through-passage tickets from Indian ports.

Current Status

Asian Canadians faced racial prejudice, despite a seemingly positive stereotype today as a model minority. The model minority stereotype is applied to a minority group that is seen as reaching significant educational, professional, and socioeconomic levels without challenging the existing establishment. This stereotype can result in unrealistic expectations, putting a stigma on members of this group that don’t meet the expectations. Stereotyping all Asians as smart, industrious, and capable can also lead to a lack of much-needed government assistance or discrimination. Asian Canadians also face a stereotype that they are passive, lack communication skills, are “techies,” or not “real” Canadians.

Chapter Summary

Racialization, Ethnicity, and Minority Groups

Race is a social construct. Ethnicity is a term that describes shared culture and national origin. Minority groups are defined in sociology by their lack of power.

Stereotypes, Prejudice, and Discrimination

Stereotypes are oversimplified ideas about groups of people. Prejudice refers to thoughts and feelings, while discrimination refers to actions. Racism refers to the belief that one group is inherently superior or inferior to other races.

Intergroup Relations and the Management of Diversity

Intergroup relations range from celebrating diversity to intolerance as severe as genocide. In pluralism, groups retain their own identity. In assimilation, groups conform to the identity of the dominant group.

Racism and Discrimination in Canada

From Indigenous people who first inhabited these lands to the waves of immigrants over the past 500 years, migration is an experience with many shared characteristics. Most groups have experienced various degrees of prejudice and discrimination.

Key Terms

assimilation: The process by which a minority individual or group takes on the characteristics of the dominant culture.

conquest: The forcible subjugation of territory and people by military action. discrimination: Prejudiced action against a group of people.

diversity: difference in abilities, age, culture, ethnicity, gender, physical characteristics, religion, sexual orientation, and values.

dominant group: A group of people who have more power in a society than any of the subordinate groups.

ethical relativism: The idea that all cultures and all cultural practices have equal value. ethnicity: Shared culture, which may include heritage, language, religion, and more.

expulsion: When a dominant group forces a subordinate group to leave a certain area or the country.

genocide: The deliberate annihilation of a targeted (usually subordinate) group.

group-specific rights: Rights conferred on individuals by their membership in a group.

institutional racism: When a societal system has developed with an embedded disenfranchisement of a group.

minority group: Any group of people who are singled out from others for differential and unequal treatment.

model minority: The stereotype applied to a minority group that is seen as reaching higher educational, professional, and socioeconomic levels without protest against the majority establishment.

multiculturalism: The recognition of cultural and racial diversity and of the equality of different cultures.

prejudice: Biased thought based on flawed assumptions about a group of people.

racial profiling: The selection of individuals for greater surveillance, policing, or treatment on the basis of racialized characteristics.

racial steering: When real estate agents direct prospective homeowners toward or away from certain neighbourhoods based on their race.

racialization: The social process by which certain social groups are marked for unequal treatment based on perceived physiological differences.

racism: A set of attitudes, beliefs, and practices used to justify the belief that one racial category is somehow superior or inferior to others.

scapegoat theory: A theory stating that the dominant group will displace its unfocused aggression onto a subordinate group.

segregation: The physical separation of two groups, particularly in residence, but also in workplace and social functions.

settler society: A society historically based on colonization through foreign settlement and displacement of Aboriginal inhabitants.

stereotypes: Oversimplified ideas about groups of people.

strategy for the management of diversity: The systematic methods used to resolve conflicts, or potential conflicts, between groups that arise based on perceived differences.

subordinate group: A group of people who have less power than the dominant group.

white privilege: The benefits people receive simply by being part of the dominant group.

visible minority: Persons, other than Indigenous persons, who are non-Caucasian in race or non-white in colour. Many disagree with eth use of this label, including the UN and the Ontario Human Rights Commission.

Chapter Quiz

8.1. Racialization, Ethnicity, and Minority Groups

- The racial term “black Canadian” can refer to _________.

- A black person living in Canada

- People whose ancestors came to Canada through the slave trade

- A white person who originated in Africa and now lives in Canada

- Any of the above

- What is the one defining feature of a minority group?

- Self-definition

- Numerical minority

- Lack of power

- Strong cultural identity

- Ethnicity describes shared _________.

- Beliefs

- Language

- Religion

- Any of the above

- Which of the following is an example of a numerical majority being treated as a subordinate group?

- Jewish people in Germany

- Creoles in New Orleans

- White people in Brazil

- Blacks under apartheid in South Africa

- Scapegoat theory shows that _________.

- Subordinate groups blame dominant groups for their problems.

- Dominant groups blame subordinate groups for their problems.

- Some people are predisposed to prejudice.

- All of the above.

8.2. Stereotypes, Prejudice, and Discrimination

- Stereotypes can be based on _________.

- Race.

- Ethnicity.

- Gender.

- All of the above.

- What is discrimination?

- Biased thoughts against an individual or group

- Biased actions against an individual or group

- Belief that a race different from yours is inferior

- Another word for stereotyping

- A Caucasian in Canada will probably deal with authority Images of the same category as them. This is an example of _________.

- Intersection theory

- Conflict theory

- White privilege

- Multiculturalism

- The Speedy Gonzales Loonie Toons cartoon character (a small Mexican speaking heavily accented English, wearing a big sombrero) is an example of _________.

- Intersection theory

- Stereotyping

- Interactionist view

8.3. Intergroup Relations and the Management of Diversity

- Which intergroup relation displays the least tolerance?

- Segregation

- Assimilation

- Genocide

- Expulsion

- What doctrine justified legal segregation in the American South?

- Jim Crow

- Plessey v. Ferguson

- De jure

- Separate but equal

- What intergroup relationship is represented by the “mosaic” metaphor?

- Assimilation

- Pluralism

- Expulsion

- Segregation

- Assimilation is represented by the _________ metaphor.

- Melting pot

- Mosaic

- Salad bowl

- Separate but equal

8.4. Racism and Discrimination in Canada

- What makes aboriginal Canadians unique as a subordinate group in Canada?

- They are the only group that experienced expulsion.

- They are the only group that was segregated.

- They are the only group that was enslaved.

- They are the only group that did not come here as immigrants.

- Which subordinate group is often referred to as the “model minority?”

- Black Canadians

- Asian Canadians

- White ethnic Canadians

- First Nations

Short Answer

8.1. Racialization, Ethnicity, and Minority Groups

How do you describe your ethnicity? Do you include your family’s country of origin? Do you consider yourself multiethnic? How does your ethnicity compare to that of the people you spend most of your time with?

8.2. Stereotypes, Prejudice, and Discrimination

- How does stereotyping contribute to institutionalized racism?

- Give an example of stereotyping that you see in everyday life. Explain what would need to happen for this to be eliminated.

8.3. Intergroup Relations and the Management of Diversity

- Do you believe immigration laws should foster pluralism, assimilation, or multiculturalism? Which perspective do you think is most supported by current Canadian immigration policies?

- Which intergroup relation do you think is the most beneficial to the subordinate group? To society as a whole? Why?

Further Research

8.1. Racialization, Ethnicity, and Minority Groups

Explore PBS’s site, Race: The power of an illusion: http://www.pbs.org/race/002_SortingPeople/002_00-home.htm

8.2. Stereotypes, Prejudice, and Discrimination

How far should multicultural rights extend? Read more about multiculturalism in a world perspective at the Multiculturalism Policies in Contemporary Democracies website: http://www.queensu.ca/mcp/home

Do you know someone who practises white privilege? Do you practise it? Explore the concept with this white privilege checklist [PDF] to see how much of it holds true for you or others: http://www.sap.mit.edu/content/pdf/white_privilege_checklist.pdf

8.3. Intergroup Relations and the Management of Diversity

So you think you know your own assumptions? Check and find out with the Implicit Association Test: https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/canada/takeatest.html

8.4. Racism and Discrimination in Canada

Are people interested in reclaiming their ethnic identities? Read this article and decide: “The White Ethnic Revival”: http://historynewsnetwork.org/article/23824

References

CBC. (2007, March 8). Term “visible minorities” may be discriminatory, UN body warns Canada. CBC News. Retrieved from http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/term-visible-minorities-may-be-discriminatory-un-body-warns-canada-1.690247.

Statistics Canada. (2013). Immigration and ethnocultural diversity in Canada: National household survey, 2011 [PDF] (Statistics Canada catalogue no. 99-010-X2011001). Retrieved from http://www12.statcan.gc.ca/nhs-enm/2011/as-sa/99-010-x/99-010-x2011001-eng.pdf.

Li, P. (1996). The making of post-war Canada. Toronto, ON: Oxford.

8.1. Racialization, Ethnicity, and Minority Groups

Dollard, J., Miller, N. E., Doob, L. W., Mowrer, O. H., & Sears, R. R. (1939). Frustration and aggression. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Milan, A., Maheux, H., & Chui, T. (2010, April 20). A portrait of couples in mixed unions. Canadian social trends, 89 (Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 11-008-X). Retrieved from http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/11-008-x/2010001/article/11143-eng.htm.

Purich, D. (1988). The Métis. Toronto, ON: James Larimer & Co.

Statistics Canada. (2010, March 9). Study: Projections of the diversity of the Canadian population. The Daily. Retrieved from http://www.statcan.gc.ca/daily-quotidien/100309/dq100309a-eng.htm.

Statistics Canada. (2011). 2011 national household survey: Data tables. (Statistics Canada catalogue no. 99-010-X2011028). Retrieved from https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/nhs-enm/2011/dp-pd/dt-td/Index-eng.cfm.

Thompson, D. (2009). Racial ideas and gendered intimacies: The regulation of interracial relationships in North America. Social and Legal Studies, 18(3), 353-371.

Wagley, C., & Harris, M. (1958). Minorities in the New World: Six case studies. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Wirth, L. (1945). The problem of minority groups. In R. Linton (Ed.), The science of man in the world crisis (p. 347). New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Hacker, H. M. (1951). Women as a minority group. Social Forces, 30. Retrieved from http://media.pfeiffer.edu/lridener/courses/womminor.html.

World Health Organization. (2011). Elder maltreatment. Fact Sheet N-357. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs357/en/index.html.

8.2. Stereotypes, Prejudice, and Discrimination

Backhouse, C. (1994, Fall). Racial segregation in Canadian legal history: Viola Desmond’s challenge, Nova Scotia, 1946. Dalhousie Law Journal, 17(2), 299-362.

Block, S., & Galabuzi, G.-E. (2011). Canada’s colour coded labour market: The gap for racialized workers. [PDF] Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. Retrieved from http://www.policyalternatives.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/publications/National%20Office/2011/03/Colour%20Coded%20Labour%20Market.pdf.

Congress of Aboriginal Peoples. (2010). Staying in school: Engaging Aboriginal students [PDF]. Retrieved from http://www.abo-peoples.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/Stay-In-School-LR.pdf.

Durkheim, É. (1982). The rules of the sociological method (W. D. Halls, Trans). New York, NY: Free Press. (Original work published 1895).

Hudson, D. L., Jr. (2009, October 16). Students lose Confederate-flag purse case in 5th Circuit. First Amendment Center. Retrieved from http://www.firstamendmentcenter.org/students-lose-confederate-flag-purse-case-in-5th-circuit.