9 Deviance

Learning Objectives

9.1. Deviance, Crime and Control

- Define deviance and categorize different types of deviant behaviour.

- Determine why certain behaviours are defined as deviant while others are not.

- Differentiate between different methods of social control.

- Understand social control as forms of government including penal social control, discipline, and risk management.

- Identify and differentiate between different types of crimes.

- Differentiate the different sources of crime statistics, and examine the falling rate of crime in Canada.

- Examine the overrepresentation of different minorities in the corrections system in Canada.

- Examine alternatives to prison.

Introduction to Deviance, Crime, and Social Control

Psychopaths and sociopaths are favourite “deviants” in pop culture: American Psycho, Hannibal Lecter, Dexter. Dangerous individuals provide fascinating fictional characters. Psychopathy and sociopathy both refer to personality disorders involving anti-social behaviour, diminished empathy and lack of inhibitions. These categories should be distinguished from psychosis, which is a condition involving a debilitating break with reality.

Psychopaths and sociopaths are often able to pass as “normal” citizens, although their manipulation and cruelty can have devastating consequences. The term psychopathy is often used to emphasize that the source of the disorder is internal, based on psychological, biological, or genetic factors. Sociopathy is used to emphasize predominant social factors in the disorder: social or familial roots and the inability to be social or abide by societal rules (Hare, 1999). In this sense, sociopathy would be a sociological disease. It involves an incapacity for companionship, although many accounts of sociopaths describe them as acting charming, attractively confident, and outgoing (Hare, 1999).

In a society with mostly secondary rather than primary relationships, the pop culture sociopath or psychopath functions as an example of social unease. The sociopath is portrayed as the nice neighbour next door who one day “goes off” or is revealed to have an evil second life. In many ways, the sociopath represents our anxieties about the loss of community and living among people we do not know. In this sense, the sociopath is a very modern sort of deviant.

In sociology, however, deviance has a much broader meaning.

9.1. Deviance, Crime and Control

What is deviance? What is the relationship between deviance and crime? According to sociologist William Graham Sumner, deviance is a violation of cultural or social norms or codified law (1906). Codified laws are norms that are written in formal codes enforced by government bodies. A crime an act of deviance that breaks not only a norm, but a law. Deviance can be as minor as nose picking in public or as major as murder.

John Hagen classifies deviant acts in terms of their perceived harmfulness and the severity of the response to them (1994). The most serious acts of deviance are consensus crimes. There is near-unanimous public agreement about consensus crimes. Acts like murder and sexual assault are usually regarded as morally intolerable, injurious, and subject to harsh penalties.

Conflict crimes are acts like prostitution or smoking cannabis. Such acts may be illegal but there is considerable public disagreement concerning their seriousness.

Social deviations are acts like abusing serving staff or behaviours arising from mental illness or addiction. Social deviations are not illegal in themselves but are widely regarded as serious or harmful. People often agree that these behaviours call for institutional intervention.

Finally there are social diversions like riding skateboards on sidewalks or facial piercings or tattoos that may be regarded as distasteful to many, or for others cool, but harmless.

“What is deviant behaviour?” cannot be answered simply. No act or person is intrinsically deviant. The sociological approach to deviance differs from moral and legalistic approaches to deviance in two important ways:

First, deviance is defined by social context. To understand why some acts are deviant and some are not, their context, the existing rules, and how these rules developed need to be understood. If the rules change, what counts as deviant also changes. Because norms vary across cultures and time, ideas about deviance also change.

Fifty years ago, public schools in Canada had strict dress codes that banned women from wearing pants to class. Today, it is socially acceptable for women to wear pants, but less so for men to wear skirts. In wartime, acts usually considered morally wrong, such as killing, may be rewarded. Much of the confusion and ambiguity about hockey violence involves the different sets of norms for inside and outside the arena. Acts that are acceptable and even encouraged on ice would be punished with jail time if they occurred on the street.

The second sociological insight is that deviance is not an intrinsic (biological or psychological) attribute of individuals. Deviance is also not intrinsic to an act. Deviance is a product of social processes. Acts themselves are not deviant. Whether an act is deviant or not depends on society’s definition. The norms themselves, or the social contexts that determine which acts are deviant or not, are continually defined and redefined through ongoing social processes—political, legal, cultural, etc. One way in which certain activities or people become defined as deviant is through the intervention of moral entrepreneurs.

Howard Becker defined moral entrepreneurs as individuals or groups who, in their own interests, publicize and problematize “wrongdoing.” Moral entrepreneurs have the power to create and enforce rules to punish wrongdoing (1963). Although Judge Emily Murphy is one of the Famous Five feminist suffragists who fought to have women legally recognized as “persons,” she was also a moral entrepreneur important in changing Canada’s drug laws. In 1922 she wrote The Black Candle which demonized the use of cannabis:

[Cannabis] has the effect of driving the [user] completely insane. The addict loses all sense of moral responsibility.

Addicts to this drug, while under its influence, are immune to pain, and could be severely injured without having any realization of their condition. While in this condition they become raving maniacs and are liable to kill or indulge in any form of violence to other persons, using the most savage methods of cruelty without, as said before, any sense of moral responsibility…. They are dispossessed of their natural and normal will power, and their mentality is that of idiots. If this drug is indulged in to any great extent, it ends in the untimely death of its addict. (Murphy, 1922)

Moral entrepreneurs can create moral panic about activities they deem deviant like cannabis use. A moral panic occurs when media-fuelled public fear lead authorities to label and repress deviants, which in turn creates a cycle in which more acts of deviance are discovered, more fear is generated, and more suppression occurs. Individuals’ deviant status is ascribed to them through social processes. Individuals are not born deviant, but become deviant through their interaction with groups, institutions, and authorities.

Through social interaction, individuals are labelled deviant or come to recognize themselves as deviant. For example, up until the 19th century, the law was mostly indifferent about who slept with whom, except where it related to marriage or property inheritance. However, in the 19th century sexuality became a matter of moral, legal, and psychological concern. The homosexual, or “sexual invert,” was defined by emerging psychiatric and biological disciplines as a psychological deviant whose instincts were contrary to nature.

In the 19th century, homosexuality was defined as a dangerous quality that defined the entire personality and moral being of an individual (Foucault, 1980). From that point until the late 1960s, homosexuality was regarded as a deviant activity that could result in legal prosecution, moral condemnation, ostracism, violent assault, and loss of career. Since then, the LGBTQ rights movement and constitutional protections of civil liberties have reversed many of the attitudes and legal structures that led to the prosecution of gays, lesbians, and transgendered people. Homosexuality as deviance was the outcome of a social process.

The symbolic interactionist approach in sociology discusses labelling theory: individuals become criminalized through contact with the criminal justice system (Becker, 1963). Prison, for example, influences individual behaviour and self-understanding, but often not in the way intended. Prisons are agents of socialization. The act of imprisonment modifies individual behaviour to make individuals more criminal. Sociological research into the social characteristics of those who encounter the criminal justice system shows that variables such as gender, age, race, and class make it more likely individuals will be processed as criminals. Social variables and power structures help us understand who becomes a criminal.

Understanding the social construction of experience leads to alternative ways of understanding and responding to issues. In studying crime and deviance, sociologists confront beliefs about a “criminal personality.”

Classifying people is a social process that Hacking called “making up people” (2006). Howard Becker called it “labelling” (1963). Crime and deviance are social constructs that vary according to

- definitions of crime

- forms and effectiveness of policing

- social characteristics of deviants

- power relations that structure society.

The social process of labelling people or activities as deviant limits the type of social responses available. Labels can be arbitrary, and the choice of label has consequences. Who gets labelled what by whom has powerful social consequences. The sociological imagination can address crime and deviance both at the individual and social levels. A deeper understanding of the social factors that produce crime and deviance allows development of more effective prevention strategies.

Making Connections: Sociology in the Real World

Why I Drive a Hearse

When Neil Young left Canada in 1966 to seek his fortune in California as a musician, he was driving his famous 1953 Pontiac hearse, Mort 2. While driving the hearse in Hollywood, he saw Stephen Stills and Richie Furray driving the other way, a fortunate encounter that led to the formation of Buffalo Springfield (McDonough, 2002). Later Young wrote the song Long May You Run as an elegy to his first hearse, Mort.

Rock musicians are often noted for their eccentricities, but is driving a hearse deviant behaviour? When sociologist Todd Schoepflin met his friend, Bill, who drove a hearse, Schoepflin wondered what effect driving a hearse had on his friend, and what effect it had on others. Would using a hearse be considered deviant by most people? Schoepflin interviewed Bill. Bill had simply been on the lookout for a reliable winter car. On a tight budget, he searched used car ads and found the hearse. He bought the vehicle because it worked well and was inexpensive.

Bill admitted that others’ reactions to the car had been mixed. His parents were horrified, and some coworkers stared. A mechanic refused to work on it, stating that it was “a dead person machine.” Bill received mostly positive reactions, however. Strangers gave him a thumbs-up on the highway and stopped him in parking lots to chat about his car. His girlfriend loved it; his friends wanted to borrow it; and people offered to buy it.

Could it be that driving a hearse isn’t deviant? Schoepflin theorized that, although outside conventional norms, driving a hearse is such a mild form of deviance that it becomes a mark of distinction.

Conformists find the choice of vehicle intriguing, while nonconformists see a fellow oddball. As one of Bill’s friends remarked, “Every guy wants to own a unique car.” Such stories remind us that although deviance is often viewed as a violation of norms, it’s not always seen in a negative light (Schoepflin, 2011).

Social Control as Sanction

When a person violates a social norm, what happens? A driver caught speeding can receive a speeding ticket. A student who texts in class gets a warning. An adult belching loudly is avoided. All societies practise social control, the enforcement of norms. Social control is an organized action intended to change people’s behaviour (Innes, 2003). Social control aims to maintain social order, practices and behaviours on which society’s members base their daily lives. Think of social order as an employee handbook, and social control as the incentives and disincentives used to encourage or oblige employees to follow those rules. When a worker violates a workplace guideline, the manager steps in to enforce the rules.

Sanctions are way to enforce rules. Sanctions can be positive as well as negative: Positive sanctions are rewards given for conforming to norms. A promotion at work is a positive sanction for working hard. Negative sanctions are punishments for violating norms. Being arrested is a punishment for shoplifting. Both types of sanctions play a role in social control.

Sociologists also classify sanctions as formal or informal. Shoplifting, a form of social deviance is illegal, but there are no laws dictating the proper way to scratch one’s nose. That doesn’t mean picking your nose in public won’t be punished; instead, there are informal sanctions. Informal sanctions emerge in face-to-face social interactions. For example, wearing flip-flops to a formal dinner or swearing loudly in church may draw disapproving looks or even verbal reprimands, but behaviour that is seen as positive — such as helping an old man carry grocery bags across the street—may receive positive informal sanctions, such as a smile or pat on the back.

Formal sanctions, on the other hand, are ways to officially recognize and enforce norm violations. A student caught plagiarizing or cheating on an exam, for example, might be expelled. Someone who speaks inappropriately to the boss could be fired. Someone who commits a crime may be arrested. On the positive side, a soldier who saves a life may receive an official commendation, or a manager might receive a bonus for increasing departmental productivity.

Social Control as Government and Discipline

Michel Foucault (1926-1984) notes that European society became increasingly concerned with social control as a government practice (Foucault, 2007). In this sense, government doesn’t simply mean activities of the state, but all the practices by which individuals or organizations govern the behaviour of others or themselves. Government refers to the strategies which seek to guide the conduct of another or others.

In the 15th and 16th centuries, many books were written on how to govern and educate children, how to govern the poor and beggars, how to govern a family or an estate, how to govern an army or a city, how to govern a state and run an economy, and how to govern one’s own conscience and conduct. These books described the growing art of government, which defined different ways to direct the conduct of individuals or groups.

Early guides to governing often just extended Christian monastic practices about government and salvation of souls. People needed to be governed in all aspects of their lives. The 19th century invention of modern institutions like the prison, public school, modern army, asylum, hospital, and factory organized ways of government and social control through the entire population.

Foucault (1979) describes these modern forms of government as disciplinary social control because they rely on detailed continuous training, control and observation of individuals. Disciplinary social control transforms

- criminalsintolawabidingcitizens,

- childrenintoeducatedandproductiveadults,

- recruits into disciplined soldiers,

- patients into healthy people, etc.

The ideal of discipline as social control is to make individuals compliant (Foucault 1979). That does not mean they become passive or sheep-like, but that disciplinary training increases their abilities, skills, and usefulness while making them more compliant.

The chief parts of disciplinary social control in modern institutions like prison and school are surveillance, normalization, and examination (Foucault, 1979). Surveillance refers to ways to make the lives and activities of individuals visible to authorities. In 1791, Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832) published his book on the ideal prison, the “seeing machine.” Prisoners’ cells would be arranged in a circle around a central observation tower where they could be both separated from each other and continually in view of prison guards. In this way social control could become automatic because prisoners would need to monitor and control their own behaviour or face sanctions.

Similarly, in a tradiitonal classroom, students sit in rows of desks visible to the teacher at the front of the room. In a store, shoppers can be observed through one-way glass or video monitors. Contemporary surveillance expands capacity for observation electronically, making activities of a population visible. London, England holds the dubious honour of the most surveilled city in the world. The city’s “ring of steel” is a security cordon in which over half a million surveillance cameras monitor and record traffic moving in and out of the city centre.

The practice of normalization refers to the way norms, such as the level of math ability expected from a grade 2 student, are first established and then used to assess, differentiate, and rank individuals according to their abilities (e.g., as an A student, B student, C student, etc.). Individuals’ progress, whether in math skills, good prison behaviour, health outcomes, or other areas, is established through constant comparisons with others. Minor sanctions are used to modify noncompliant behaviour. Rewards are applied for good behaviour and penalties for bad.

Periodic examinations through testing in schools, medical examinations in hospitals, inspections in prisons, year-end reviews in the workplace, etc. bring together surveillance and normalization in a way that allows individuals to be assessed, documented, and known by authorities. Based on examinations, individuals can receive different disciplinary procedures. Gifted children might receive an enriched educational program; weaker students might receive remedial lessons.

Formal laws, courts, and the police intervene when laws are broken, but disciplinary techniques allow continuous social control of activities through surveillance, normalization, and examination. While we may never break a law, if we work, go to school or hospital, we are routinely subject to disciplinary control through most of the day.

Social Control as Risk Management

Some recent types of social control adopt a risk management model for some problematic behaviours. Risk management refers to interventions designed to reduce the likelihood of undesirable events occurring based on risk probability. Risk management is unlike the crime and punishment model of penal social sanctions or the rehabilitation, training, or therapeutic models of disciplinary social control Risk management strategies do not control individual deviants. Risk management strategies attempt to restructure the environment of problematic behaviour to minimize the risks to the general population.

For example, the public health model for controlling intravenous drug use does not focus on criminalizing drug use or making users to “kick drugs” (O’Malley, 1998). It recognizes that fines or imprisonment do not curtail drug use, and that therapeutic rehabilitation of drug use is not only expensive but unlikely to succeed unless drug users are willing. Instead, the public health model calculates the risk of deaths from drug overdoses and the danger to the general population from the transmission of disease (like HIV and hepatitis C). It then attempts to modify the riskiest behaviours through targeted interventions. Programs like needle exchanges (designed to prevent the sharing of needles) or safe-injection-sites (designed to provide sanitary conditions for drug injection and immediate medical services for overdoses) do not prevent addicts from using drugs but minimize the harms resulting from drug use by modifying the environment in which drugs are injected. Reducing risks to public health is the priority of the public health model.

In the case of crime, the new penology strategies of social control are also less concerned with criminal responsibility, moral condemnation, or rehabilitative intervention (Feely & Simon, 1992). New penology strategies identify, classify, and manage groupings of offenders sorted by the degree of dangerousness they represent to the public. In this way, imprisonment is used to incapacitate those who represent a significant risk, but probation and various levels of surveillance are used for those who represent a lower risk. Examples include sex offender tracking and monitoring, or the use of electronic monitoring ankle bracelets for low-risk offenders. New penology strategies seek to regulate levels of deviance, not intervene or respond to individual deviants or the social determinants of crime.

Similarly, situational crime control redesigns spaces where crimes or deviance could occur to minimize the risk of crimes occurring (Garland, 1996). Using alarm systems, CCTV surveillance cameras, adding or improving lighting, broadcasting irritating sounds, or making street furniture uncomfortable are all ways of working on the cost/benefit analysis of potential deviants or criminals before they act, rather than acting directly on the deviants or criminals themselves.

9.2. Crime and the Law

The sociological study of crime, deviance, and social control is especially important for public policy debates. In 2012 the Conservative government passed the Safe Streets and Communities Act, a controversial piece of legislation because it introduced mandatory minimum sentences for certain drug or sex related offences, restricted the use of conditional sentencing (non-prison punishments), imposed harsher sentences on certain categories of young offender, reduced the ability for Canadians with a criminal record to receive a pardon, and made it more difficult for Canadians imprisoned abroad to transfer back to a Canadian prison to be near family and support networks. The legislation imposed a mandatory six-month sentence for cultivating six cannabis plants, for example. This followed the Tackling Violent Crime Act passed in 2008, which, among other provisions, imposed a mandatory three-year sentence for first-time gun-related offences.

This government policy represented a shift toward a punitive approach to crime control and away from preventive strategies such as drug rehabilitation, prison diversion, and social reintegration programs. Despite the evidence that rates of serious and violent crime have been falling in Canada, and while even some U.S. conservative politician have begun to reject the punitive approach as an expensive failure, the government pushed the legislation through Parliament. In response to evidence that questions the need for more punitive measures of crime control, then Justice Minister Rob Nicholson said, “Unlike the Opposition, we do not use statistics as an excuse not to get tough on criminals. As far as our Government is concerned, one victim of crime is still one too many” (Galloway, 2011).

What accounts for the appeal of “get tough on criminals” policies at a time when crime rates are falling and at their lowest level since 1972 (Perreault, 2013)? One reason is that violent crime is a form of deviance that lends itself to spectacular media coverage. Such coverage distorts the actual public threat.

Television news frequently begins with “chaos news” — crime, accidents, natural disasters — that present an image of society as a dangerous and unpredictable. However, this image of crime doesn’t accurately represent the types of crime that occur. The news typically reports on the worst sorts of violent crime, but violent crime made up only 21 percent of all police-reported crime in 2012 (down 17 percent from 2002). Homicides made up only one-tenth of 1 percent of all violent crimes in 2012 (down 16 percent from 2002). In 2012, the homicide rate fell to its lowest level since 1966 (Perreault, 2013). Moreover, an analysis of television news reporting on murders in 2000 showed that while 44 percent of CBC news coverage and 48 percent of CTV news coverage focused on murders committed by strangers, only 12 percent of murders in Canada are committed by strangers. Similarly, while 24 percent of the CBC reports and 22 percent of the CTV reports referred to murders in which a gun had been used, only 3.3 percent of all violent crime involved a gun in 1999. In 1999, 71 percent of violent crimes in Canada did not involve any weapon (Miljan, 2001).

This distortion creates the conditions for moral panic around crime. As we noted earlier, a moral panic occurs when a relatively minor or atypical situation of deviance is amplified and distorted by the media, police, or members of the public. The deviance becomes defined as a general threat to society (Cohen, 1972). Public attention focusses the situation, so more instances are discovered, the deviants are rebranded as “folk devils,” and authorities react by taking social control measures disproportionate to the acts of deviance.

For example, the implementation of mandatory minimum sentences for the cannabis cultivation in the Safe Streets and Communities legislation was said to be in response to the infiltration of organized crime into Canada. For years newspapers uncritically published stories on the cannabis trade, describing it as widespread, gang-related, and linked to the cross-border trade in guns and more serious drugs like heroin. Television news coverage often shows police in white, disposable hazardous-waste outfits removing cannabis plants from suburban houses, and presents exaggerated estimates of street value.

However, a 2011 Justice Department study revealed that out of a random sample of 500 grow-ops, only 5 percent had connections to organized crime. A 2005 RCMP-funded study noted that “firearms or other hazards” were found in only 6 percent of grow-op cases examined (Boyd & Carter, 2014). While 76 percent of Canadians believe that cannabis should be legally available (Stockwell et al., 2006), and several jurisdiction have legalized cannabis, the Safe Streets and Communities Act tried to reinvigorate the punitive messaging of the “war on drugs” based on disinformation and moral panic.

What Is Crime?

Although deviance is a violation of social norms, it is not always punishable, and it is not necessarily bad. Crime, on the other hand, is a behaviour that violates official law and is punishable through formal sanctions. Walking to class backwards is a deviant behaviour. Driving with a high blood alcohol level is a crime. Like other forms of deviance, however, ambiguity exists concerning what constitutes a crime and whether all crimes are, in fact, “bad” and deserve punishment. For example, in 1946 Viola Desmond refused to sit in the balcony designated for blacks at a cinema in New Glasgow, Nova Scotia. She was dragged from the cinema by two men. She was then arrested, obliged to stay overnight in the male cell block, tried without counsel, and fined.

The courts ignored the issue of racial segregation in Canada. Instead her crime was said to be tax evasion because she had not paid the 1 cent difference in tax between a balcony ticket and a main floor ticket. She took her case to the Supreme Court of Nova Scotia where she lost. Long after her death, she was posthumously pardoned because the application of the law was clearly in violation of norms of social equality.

All societies have informal and formal ways of maintaining social control. Within these systems of norms, societies have legal codes that maintain formal social control through laws, which are rules adopted and enforced by a political authority. Those who violate these rules incur negative formal sanctions. Normally, punishments are relative to the degree of the crime and the importance to society of the value underlying the law. However, there are other factors that influence criminal sentencing.

Types of Crimes

Not all crimes are given equal weight. Society socializes its members to view certain crimes as more severe than others. For example, most people consider murdering someone to be far worse than stealing a wallet. They expect a murderer to be punished more severely than a thief. In modern North American society, crimes are classified as one of two types based on their severity. Violent crimes (also known as “crimes against a person”) are based on the use of force or the threat of force. Rape, murder, and armed robbery fall under this category. Nonviolent crimes involve the destruction or theft of property, but do not use force or the threat of force. They are also sometimes called “property crimes.” Larceny, car theft, and vandalism are all types of nonviolent crimes. If you use a crowbar to break into a car, you are committing a nonviolent crime; if you mug someone with the crowbar, you are committing a violent crime.

When we think of crime, we often picture street crime, or offences committed by ordinary people against other people or organizations, usually in public spaces. We often overlook corporate crime, crime committed by white-collar workers in a business environment. Embezzlement, insider trading, and identity theft are all types of corporate crime. Although these types of offences rarely receive the same media coverage as street crimes, they can be far more damaging. The 2008 world economic recession was the result of a financial collapse triggered by corporate crime.

An often-debated third type of crime is victimless crime. These are called victimless because the perpetrator is not explicitly harming another person. As opposed to battery or theft, which clearly have a victim, a crime like drinking a beer at age 17 or selling a sexual act do not result in injury to anyone other than the individual who engages in them. While some claim acts like these are victimless, others argue that they actually harm society. Prostitution may foster abuse toward women by clients or pimps. Drug use may increase the likelihood of employee absences. Such debates highlight how the deviant and criminal nature of actions develops through ongoing public discussion.

Making Connections: Sociological Research

Hate Crimes

The skinheads were part of a group that called itself White Power. They had been to an all-night drinking party when they decided they were going to vandalize some cars in the temple parking lot. They encountered the caretaker Nirmal Singh Gill and took turns attacking him.

The eldest of the skinheads had recently been released from the military because of his racist beliefs. Another had a large Nazi flag pinned to the wall of his apartment. In a telephone call intercepted during the investigation, one skinhead was recorded as saying, “Can’t go wrong with a Hindu death cause it always sends a f’n message” (R. v. Miloszewski, 1999).

Attacks motivated by hate based on a person’s race, religion, or other characteristics are hate crimes. The category of hate crimes grew out of the provisions in the Criminal Code that prohibit hate propaganda (sections 318 and 319) including advocating genocide, public incitement of hatred, or willful promotion of hatred against an identifiable group.

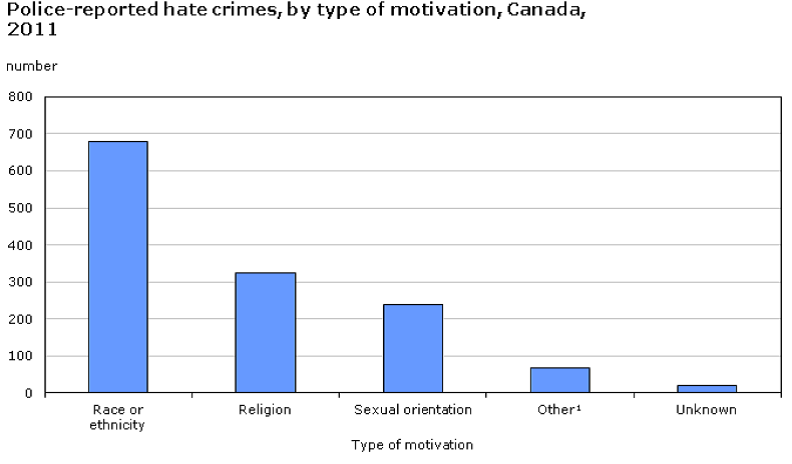

In 1996, section 718.2 of the Criminal Code was amended to introduce hate motivation as an aggravating factor in crime that needed to be considered in sentencing (Silver et al., 2004). In 2009 Statistics Canada reported that 5 percent of the offences experienced by victims of crime in Canada were believed by the victims to be motivated by hate (approximately 399,000 incidents in total) (Perreault & Brennan, 2010). However, hate crimes reported to police in 2009 totaled only 1,473. About one-third of the General Social Survey respondents said they reported the hate-motivated incidents to the police. In 2011 police-reported hate crimes had dropped to 1,322 incidents.

The majority of these were racially or ethnically motivated, but many were based on religious prejudice (especially anti-Semitic) or sexual orientation. A significant portion of the hate-motivated crimes (50 percent) involved mischief (vandalism, graffiti, and other destruction of property). This figure increased to 75 percent for religious- motivated hate crimes. Violent hate crimes constituted 39 percent of all hate crimes (22 percent accounted for by violent assault specifically). Sexual-orientation-motivated hate crimes were the most likely to be violent (65 percent) (Allen & Boyce, 2013).

Crime Statistics

What crimes are people in Canada most likely to commit, and who is most likely to commit them? To understand criminal statistics, first understand how statistics are collected. Since 1962, Statistics Canada has been collecting and publishing crime statistics known as the Uniform Crime Reports Survey (UCR). These annual publications contain data from all the police agencies in Canada. Although the UCR contains comprehensive data on police reports, it don’t account for the many crimes unreported. Victims are often unwilling to report, largely based on fear, shame, or distrust of the police. Data accuracy of the UCR also varies greatly. Because police and other authorities decide which criminal acts to focus on, the data reflects the priorities of the police rather than actual levels of crime. For example, if police decide to focus on gun-related crimes, more gun-related crimes will be discovered and counted.

Similarly, changes in legislation to introduce new crimes or change the categories under which crimes are recorded will also alter the statistics. To address some of these problems, in 1985, Statistics Canada began to publish a separate report known as the General Social Survey on Victimization (GSS). The GSS is a self-report study. A self-report study is a collection of data acquired using voluntary response methods, based on telephone interviews. In 2014, for example, survey data were gathered from 79,770 households across Canada on the frequency and type of crime they experience. The surveys are thorough, providing a wider scope of information than was previously available. This allows researchers to examine crime from more detailed perspectives and to analyze the data based on factors such as the relationship between victims and offenders, the consequences of the crimes, and substance abuse involved in the crimes. Demographics are also analyzed, such as age, ethnicity, gender, location, and income level.

The Declining Crime Rate in Canada

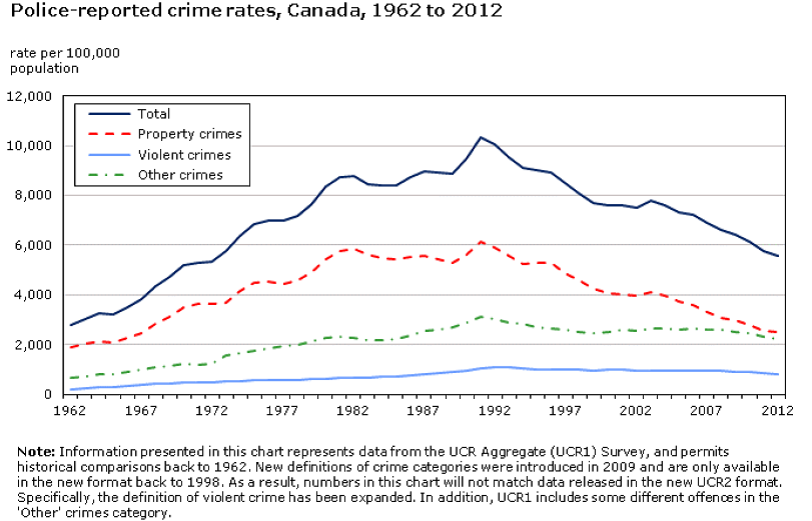

While neither of these publications can describe all crimes committed in Canada, general trends are identified. Crime rates were on the rise after 1960, but following an all-time high in the 1980s and 1990s, rates of violent and nonviolent crimes started to decline. In 2012 they reached their lowest level since 1972 (Perreault, 2013).

Source: Perreault, 2013

In 2012, approximately 2 million crimes occurred in Canada. Of those, 415,000 were classified as violent crimes, mostly assault and robbery. The rate of violent crime reached its lowest level since 1987, led by decreases in sexual assault, common assault, and robbery. The homicide rate fell to its lowest level since 1966.

An estimated 1.58 million nonviolent crimes also took place, most common being theft under $5,000 and mischief. The declining crime rate is mostly due to decreases in nonviolent crime, especially decreases in mischief, break-ins, disturbing the peace, motor vehicle theft, and possession of stolen property. However, only 31 percent of violent and nonviolent crimes were reported to the police.

Opinion polls continue to show that most Canadians believe that crime rates, especially violent crime rates, are rising (Edmiston, 2012), even though the statistics show a steady decline since 1991. Where is the disconnect? There are three primary reasons for the decline in the crime rate.

- First, demographic changes to the Canadian population: Most crime is committed by people aged 15 to 24. This age cohort has declined in size since 1991.

- Second, male unemployment is highly correlated with the crime rate. Following the recession of 1990–1991, better economic conditions improved male unemployment.

- Third, police methods have arguably improved since 1991, including having a more targeted approach to sites and types of crime. While reporting on spectacular crime has not diminished, the underlying social and policing conditions have.

Lower crime rates may be overlooked because of TV and social media daily recital of violent and frightening crime.

Corrections

The corrections system, more commonly known as the prison system, supervises those who have been arrested, convicted, and sentenced for a criminal offence. At the end of 2011, approximately 38,000 adults were in prison in Canada, while another 125,000 were under community supervision or probation (Dauvergne, 2012). In contrast, seven million Americans were behind bars in 2010 (Bureau of Justice Statistics, 2011). Canada’s 2011 rate of adult incarceration was 140 per 100,000 population. In the United States in 2008, the incarceration rate was approximately 1,000 per 100,000 population. More than 1 in 100 U.S. adults were in jail or prison, the highest in U.S. history. While Americans account for 5 percent of the global population, they have 25 percent of the world’s inmates, the largest number of prisoners in the world (Liptak, 2008). While Canada’s incarceration rate is far lower than the United States’, there are some very disturbing features of the Canadian corrections system.

From 2010 to 2011, Indigenous Canadians were 10 times more likely to be incarcerated than the non-Indigenous population. While Indigenous people accounted for about 4 percent of the Canadian population, in 2013, they made up 23.2 percent of the federal penitentiary population. Indigenous women made up 33.6 percent of incarcerated women in Canada. This problem of overrepresentation of Indigenous people in the corrections system—the difference between the proportion of Indigenous people incarcerated in Canadian correctional facilities and their proportion in the general population—continues to grow appreciably despite a Supreme Court ruling in 1999 (R. vs. Gladue) that the social history of Indigenous offenders should be considered in sentencing. Section 718.2 of the Criminal Code states, “all available sanctions other than imprisonment that are reasonable in the circumstances should be considered for all offenders, with particular attention to the circumstances of Indigenous offenders.” Prison is supposed to be used only as a last resort. Nevertheless, between 2003 and 2013, the Indigenous population in prison grew by 44 percent (Correctional Investigator Canada, 2013).

Hartnagel summarized the research about why Indigenous people are overrepresented in the criminal justice system (2004).

- First, Indigenous people are disproportionately poor. Poverty is associated with higher arrest and incarceration rates. Unemployment in particular is correlated with higher crime rates.

- Second, Indigenous lawbreakers tend to commit more detectable street crimes than the less detectable white-collar crimes of other segments of the population.

- Third, the criminal justice system disproportionately profiles and discriminates against Indigenous people. It is more likely for Indigenous people to be apprehended, processed, prosecuted, and sentenced than non-Indigenous people.

- Fourth, the legacy of colonization has disrupted and weakened traditional sources of social control in Indigenous communities. The informal social controls that effectively control criminal and deviant behaviour in intact communities have been compromised in Indigenous communities due to forced assimilation, the residential school system, and migration to poor inner city neighbourhoods.

Although Black Canadians are a smaller minority of the Canadian population than Indigenous people, they experience a similar problem of overrepresentation in the prison system. Blacks represent approximately 2.9 percent of the Canadian population, but make up 9.5 percent of the total prison population in 2013, up from 6.3 percent in 2003–2004 (Correctional Investigator Canada, 2013). A survey revealed that blacks in Toronto are subject to racial profiling by the police, which might partially explain their higher incarceration rate (Wortley, 2003).

Racial profiling occurs when police single out a racialized group for extra policing, including a disproportionate use of stop-and-search practices (i.e. “carding”), undercover sting operations, police patrols in racialized minority neighbourhoods, and extra attention at border crossings and airports. Survey respondents revealed that Blacks in Toronto were much more likely to be stopped and searched by police than were whites or Asians. Moreover, in a reverse of the situation for whites, older and more affluent Black males were more likely to be stopped and searched than younger, lower-income blacks. As one survey respondent put it: “If you are Black and drive a nice car, the police think you are a drug dealer or that you stole the car. They always pull you over to check you out” (Wortley, 2003).

Prisons and their Alternatives

Recent public debates in Canada about being “tough on crime” often assume that imprisonment and mandatory minimum sentences are effective crime control practices. Common sense might suggest that harsher penalties deter offenders from committing more crimes after release from prison. However, research shows that serving prison time does not reduce the tendency to re-offend.

In general, the effect of imprisonment on recidivism — the likelihood for people to be arrested again — was either non-existent or increased the likelihood of re-offence in comparison to non-prison sentences (Nagin, Cullen, & Jonson, 2009). In particular, first time offenders sent to prison have higher rates of recidivism than similar offenders sentenced to community service (Nieuwbeerta, Nagin, & Blockland, 2009).

Moreover, the collateral effects of the imprisonment of one family member include negative impacts on other family members and communities, including increased aggressiveness of young sons (Wildeman, 2010) and increased likelihood that the children of incarcerated fathers will commit offences as adults (van de Rakt & Nieuwbeerta, 2012). Some researchers identify a penal-welfare complex to describe the creation of inter-generational criminalized populations who are excluded from participating in society or holding regular jobs (Garland, 1985). Petty crimes like theft, public consumption of alcohol, drug use, etc. enable those trapped in generational criminal activity to get by in the absence of regular sources of security and income. These petty crimes are increasingly targeted by zero tolerance and minimum sentencing policies, making the cycle harder to break.

Alternatives to prison sentences can be used as criminal sanctions. In Canada, these include fines, electronic monitoring, probation, and community service. These alternatives divert offenders from penal social control, based on principles drawn from labelling theory. They emphasize

- compensatory social control, which obliges an offender to pay a victim to compensate for a harm committed;

- therapeutic social control, which involves the use of therapy to return individuals to a normal state;

- and conciliatory social control, which reconciles the parties of a dispute to mutually restore harmony to a social relationship that has been damaged.

Many non-custodial sentences involve community-based sentencing, in which offenders serve a conditional sentence in the community, usually by performing some sort of community service. Some research shows that rehabilitation is more effective if the offender is in the community rather than prison. A version of community-based sentencing is restorative justice conferencing, which focuses on establishing a direct, face- to-face connection between the offender and the victim. The offender is obliged to make restitution to the victim, thus “restoring” a situation of justice. Part of the process of restorative justice is to lead the offender to fully acknowledge responsibility for the offence, express remorse, and make a meaningful apology to the victim (Department of Justice, 2013).

In special cases where the parties agree, Indigenous sentencing circles involve victims, the Indigenous community, and Indigenous elders in a process of deliberation with Indigenous offenders to determine the best way to find healing for the harm done to victims and communities. This is a form of traditional Indigenous justice, which centres on healing and building community rather than retribution. These might involve specialized counselling or treatment programs, community service under the supervision of elders, or the use of an Indigenous nation’s traditional penalties (Indigenous Justice Directorate, 2005).

It is difficult to find data in Canada on the effectiveness of these types of programs. However, a large meta- analysis examined ten studies from Europe, North America, and Australia. This study determined that restorative justice conferencing was effective in reducing rates of recidivism and criminal justice system costs (Strang et al., 2013). Recidivism was reduced between 7 and 45 percent from traditional penal sentences by using restorative justice conferencing.

Rehabilitation and recidivism are, of course, not the only goals of the corrections systems. Many people are skeptical about the capacity of offenders to be rehabilitated and see criminal sanctions as a means of (a) deterrence to prevent crimes, (b) retribution or revenge to address harms to victims and communities, or (c) incapacitation to remove dangerous individuals from society.

Conclusions

The sociological study of crime, deviance, and social control is especially important for public policy debates. Often, in the news and public debate, how best to respond to crime is framed in moral terms; therefore, for example, the policy alternatives get narrowed to the option of either being “tough” on crime or “soft” on crime. Tough and soft are moral categories.

Debating with these moral terms limits solutions and undermines the ability to raise questions about effective responses to crime. Policy debates over crime seem susceptible to “non-science” discussed in Chapter 2: Sociological Research. The story of an isolated individual crime becomes the basis for belief in a failed criminal justice system. This shows overgeneralization and knowledge based on selective evidence. Moral categories of judgement frame problems unscientifically.

The sociological approach is different. Sociology focuses on the effectiveness of social control strategies for addressing criminal behaviour and risk to public safety. Sociologists think systematically about who commits crimes and why. Sociologists look at the big picture to see why certain acts are considered normal and others deviant, or why certain acts are criminal, and others are not. In a society with large inequalities of power and wealth, sociologists ask who gets to define whom as criminal.

This chapter illustrates the sociological imagination at work by examining the “individual troubles” of criminal behaviour and victimization within the social structures that sustain them. Sociology advocates evidence-based and systematic policy options.

Chapter Summary

Deviance is a violation of norms. Whether or not something is deviant depends on contextual definitions, the situation, and people’s response to the behaviour. Society seeks to limit deviance with sanctions that help maintain a system of social control. In modern normalizing societies, disciplinary social control is a primary governmental strategy of social control.

Key Terms

community-based sentencing: Offenders serve a conditional sentence in the community, usually by performing some sort of community service.

consensus crimes: Serious acts of deviance about which there is near-unanimous public agreement.

conflict crimes: Acts of deviance that may be illegal but about which there is considerable public disagreement concerning their seriousness.

corporate crime: Crime committed by white-collar workers in a business environment.

corrections system: The system tasked with supervising individuals who have been arrested, convicted, or sentenced for criminal offences.

crime: A behaviour that violates official law and is punishable through formal sanctions.

criminal justice system: An organization that exists to enforce a legal code.

deviance: A violation of contextual, cultural, or social norms.

disciplinary social control: Detailed continuous training, control, and observation of individuals to improve their capabilities.

examination: The use of tests by authorities to assess, document, and know individuals.

formal sanctions: Sanctions that are officially recognized and enforced.

government: Practices by which individuals or organizations seek to govern the behaviour of others or themselves.

hate crimes: Attacks based on a person’s race, religion, or other characteristics.

Indigenous sentencing circles: The involvement of Indigenous communities in the sentencing of Indigenous offenders.

informal sanctions: Sanctions that occur in face-to-face interactions.

labelling theory: The ascribing of a deviant behaviour to another person by members of society.

law: Norms that are specified in explicit codes and enforced by government bodies.

legal codes: Codes that maintain formal social control through laws.

moral entrepreneur: An individual or group who, to serve self-interest, publicizes and problematizes “wrongdoing” and has the power to create and enforce rules to penalize wrongdoing.

moral panic: An expanding cycle of deviance, media-generated public fears, and police repression.

negative sanctions: Punishments for violating norms.

nonviolent crimes: Crimes that involve the destruction or theft of property, but do not use force or the threat of force.

normalization: The process by which norms are used to differentiate, rank, and correct individual behaviour.

normalizing society: A society that uses continual observation, discipline, and correction of its subjects to exercise social control.

overrepresentation: The difference between the proportion of an identifiable group in a particular institution (like the correctional system) and their proportion in the general population.

penal social control: A means of social control that prohibits certain social behaviours and responds to violations with punishment.

penal-welfare complex: The network of institutions that create and exclude inter-generational, criminalized populations on a semi-permanent basis.

police: A civil force in charge of regulating laws and public order at a federal, state, or community level.

positive sanctions: Rewards given for conforming to norms.

power elite: A small group of wealthy and influential people at the top of society who hold the power and resources.

psychopathy: A personality disorder characterized by anti-social behaviour, diminished empathy, and lack of inhibitions.

racial profiling: The singling out of a particular racial group for extra policing.

recidivism: The likelihood for people to be arrested again after an initial arrest.

restorative justice conferencing: Focuses on establishing a direct, face-to-face connection between the offender and the victim.

sanctions: The means of enforcing rules.

self-report study: Collection of data acquired using voluntary response methods, such as questionnaires or telephone interviews.

situational crime control: Strategies of social control that redesign spaces where crimes or deviance could occur to minimize the risk of crimes occurring there.

social control: The regulation and enforcement of norms.

social deviations: Deviant acts that are not illegal but are widely regarded as harmful.

social diversions: Acts that violate social norms but are generally regarded as harmless.

social order: An arrangement of practices and behaviours on which society’s members base their daily lives.

sociopathy: A personality disorder characterized by anti-social behaviour, diminished empathy, and lack of inhibitions.

street crime: Crime committed by average people against other people or organizations, usually in public spaces.

surveillance: Various means used to make the lives and activities of individuals visible to authorities.

therapeutic social control: A means of social control that uses therapy to return individuals to a normal state.

traditional Indigenous justice: Centred on healing and building community rather than retribution.

victimless crime: Activities against the law that do not result in injury to any individual other than the person who engages in them.

violent crimes (also known as “crimes against a person”): Based on the use of force or the threat of force.

white-collar crime: Crimes committed by high status or privileged members of society.

Chapter Quiz

- Which of the following best describes how deviance is defined?

- Deviance is defined by federal, provincial, and local laws.

- Deviance’s definition is determined by one’s religion.

- Deviance occurs whenever someone else is harmed by an action.

- Deviance is socially defined.

- In 1946, Viola Desmond was arrested for refusing to sit in the blacks-only section of the cinema in Nova Scotia. This is an example of______________.

- A consensus crime

- A conflict crime

- A social deviation

- A social diversion

- A student has a habit of texting during class. One day, the professor stops his lecture and asks her to respect the other students in the class by turning off her phone. In this situation, the professor used __________ to maintain social control.

- Informal positive sanctions

- Formal negative sanction

- Informal negative sanctions

- Formal positive sanctions

- Societies practise social control to maintain ________.

- Formal sanctions

- Social order

- Cultural deviance

- Sanction labelling

- Which of the following is an example of corporate crime?

- Embezzlement

- Larceny

- Assault

- Burglary

- Spousal abuse is an example of a ________.

- Street crime

- Corporate crime

- Violent crime

- Nonviolent crime

- Which of the following situations best describes crime trends in Canada?

- Rates of violent and nonviolent crimes are decreasing.

- Rates of violent crimes are decreasing, but there are more nonviolent crimes now than ever before.

- Crime rates have skyrocketed since the 1970s due to lax court rulings.

- Rates of street crime have gone up, but corporate crime has gone down.

- What is a disadvantage of crime victimization surveys?

- They do not include demographic data, such as age or gender.

- They may be unable to reach important groups, such as those without phones.

- They do not address the relationship between the criminal and the victim.

- They only include information collected by police officers.

- A convicted sexual offender is released on parole and arrested two weeks later for repeated sexual crimes. How would labelling theory explain this?

- The offender has been labelled deviant by society and has accepted this master status.

- The offender has returned to his old neighbourhood and so re-established his former habits.

- The offender has lost the social bonds he made in prison and feels disconnected from society.

- The offender is poor and coping with conditions of oppression and inequality

Short Answer

-

If given the choice, would you purchase an unusual car such as a hearse for everyday use? How would your friends, family, or significant other react? Since deviance is culturally defined, most of the decisions we make are dependent on the reactions of others. Is there anything the people in your life encourage you to do that you don’t do? Why do you resist their encouragement?

-

Think of a recent time when you used informal negative sanctions. To what act of deviance were you responding? How did your actions affect the deviant person or persons? How did your reaction help maintain social control?

Recall the crime statistics presented in this chapter. Do they surprise you? Are these statistics represented accurately in the media? Why does the public perceive that crime rates are increasing and believe that punishment should be stricter when actual crime rates have been steadily decreasing?

Further Research

Although we rarely think of it in this way, deviance can have a positive effect on society. Check out the Positive Deviance Initiative, a program initiated by Tufts University to promote social movements around the world that strive to improve people’s lives: http://www.positivedeviance.org/.

Crime is established by legal codes and upheld by the criminal justice system. The corrections system is the dominant system of criminal punishment, but a number of community-based sentencing models offer alternatives that promise more effective outcomes in terms of recidivism. Although crime rates increased throughout most of the 20th century, they have been dropping since their peak in 1991.

How is crime data collected in Canada? Read about the victimization survey used by Statistics Canada and take the survey yourself: http://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p2SV.pl?Function=getSurvey&SDDS=4504.

References

9. Introduction to Deviance, Crime, and Social Control

Fallon, J. (2013). The psychopath inside: A neuroscientist’s personal journey into the dark side of the brain. New York, NY: Current.

Hacking, I. (2006, August). Making up people. London Review of Books, 28(16/17), 23-26.

Hare, R. D. (1999). Without conscience: The disturbing world of the psychopaths among us. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Rimke, H. (2011). The pathological approach to crime. In Kirstin Kramar (Ed.), Criminology: critical Canadian perspectives (pp. 79-92). Toronto, ON: Pearson.

Becker, H. (1963). Outsiders: Studies in the sociology of deviance. New York, NY: Free Press.

Black, D. (1976). The behavior of law. New York, NY: Academic Press.

Feely, M., & Simon, J. (1992). The new penology: Notes on the emerging strategy of corrections and its implications. Criminology, 30(4), 449-474.

Foucault, M. (1979). Discipline and punish: The birth of the prison. New York, NY: Vintage Books.

Foucault, M. (1980). The history of sexuality volume 1: An introduction. New York, NY: Vintage Books.

Foucault, M. (2007). The politics of truth. Los Angeles, CA: Semiotext(e).

Hacking, I. (2006, August). Making up people. London Review of Books, 28(16/17), 23-26.

Garland, D. (1996). The limits of the sovereign state: Strategies of crime control in contemporary society. British Journal of Criminology, 36(4), 445-471.

Hagen, J. (1994). Crime and disrepute. Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press.

Innes, M. (2003). Understanding social control: Deviance, crime and social order. Maidenhead, UK: Open University Press.

McDonough, J. (2002). Shakey: Neil Young’s biography. New York, NY: Random House.

Murphy, E. (1973). The black candle. Toronto, ON: Coles Publishing. (Original work published 1922).

O’Malley, P. (1998). Consuming risks: Harm minimization and the government of ‘drug-users.’ In Russell Smandych (Ed.), Governable places: Readings on governmentality and crime control. Brookfield, VT: Ashgate.

Schoepflin, T. (2011, January 28). Deviant while driving? [Blog post]. Everyday Sociology Blog. Retrieved from http://nortonbooks.typepad.com/everydaysociology/2011/01/deviant-while-driving.html.

Sumner, W. G. (1955). Folkways. New York, NY: Dover. (Original work published 1906).

Department of Justice Canada, Aboriginal Justice Directorate. (2005, December). Aboriginal justice strategy annual activities report 2002-2005. [PDF] Retrieved from http://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/aj-ja/0205/rep-rap.pdf.

Allen, M., & Boyce, J. (2013). Police-reported hate crime in Canada, 2011. [PDF] (Statistics Canada catologue no. 85-002-X). Retrieved from http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/85-002-x/2013001/article/11822-eng.pdf.

Boyd, S., & Carter, C. (2014). Killer weed: Marijuana grow ops, media, and justice. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press.

Bureau of Justice Statistics. (2011). U.S. correctional population declined for second consecutive year. Retrieved from http://bjs.ojp.usdoj.gov/content/pub/press/p10cpus10pr.cfm.

Cohen, S. (1972). Folk devils and moral panics. London, UK: MacGibbon & Kee.

Correctional Investigator Canada. (2013). Annual report of the Office of the Correctional Investigator: 2012-2013 [PDF]. Retrieved from http://www.oci-bec.gc.ca/cnt/rpt/pdf/annrpt/annrpt20122013-eng.pdf.

Dauvergne, M. (2012, October 11). Adult correctional statistics in Canada, 2010/2011. [PDF] Juristat. (Statistics Canada catologue No. 85-002-X). Retrieved from http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/85-002-x/2012001/article/11715-eng.pdf.

Department of Justice Canada. (2013, April 30). Community-based sentencing: The perspectives of crime victims. Retrieved from http://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/cj-jp/victim/rr04_vic1/p1.html.

Edmiston, J. (2012, August 4). Canada’s inexplicable anxiety over violent crime. National Post. Retrieved from http://news.nationalpost.com/2012/08/04/canadas-inexplicable-anxiety-over-violent-crime/.

Galloway, G. (2011, July 21). Crime falls to 1973 levels as Tories push for sentencing reform. The Globe and Mail. Retrieved from http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/politics/crime-falls-to-1973-levels-as-tories-push-for-sentencing-reform/article600886.

Garland, D. (1985). Punishment and welfare: A history of penal strategies. Brookfield, VT: Gower Publishing.

Liptak, A. (2008, April 23). Inmate count in U.S. dwarfs other nations’. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2008/04/23/us/23prison.html?ref=adamliptak.

Miljan, L. (2001, March). Murder, mayhem, and television news. Fraser Forum, 17-18.

Perreault, S. (2013, July 25). Police-reported crime statistics in Canada, 2012. [PDF] Jurisdat. (Statistics Canada catologue no. 85-002-X). Retrieved from http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/85-002-x/2013001/article/11854-eng.pdf.

Perreault, S. & Brennan, S. (2010, Summer). Criminal victimization in Canada, 2009. Juristat. (Statistics Canada catologue no. 85-002-X). Retrieved from http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/85-002-x/2010002/article/11340-eng.htm#a18.

R. v. Miloszewski. (1999, November 16). BCJ No. 2710. British Columbia Provincial Court.

Nagin, D., Cullen, F., & Lero Jonson, C. (2009). Imprisonment and reoffending. In M. Tonry (Ed.), Crime and Justice: A Review of Research, 38. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Nieuwbeerta, P., Nagin, D., & Blokland, A. (2009). Assessing the impact of first-time imprisonment on offenders’ subsequent criminal career development: A matched sample comparison. [PDF] Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 25, 227-257.

Silver, W., Mihorean, K., & Taylor-Butts, A. (2004). Hate crime in Canada. Juristat, 24(4). (Statistics Canada catologue no. 85-002-XPE). Retrieved from http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/85-002-x/85-002-x2004004-eng.pdf.

Stockwell, T., Sturge, J., Jones, W., Fischer, B., & Carter, C. (2006, September). Cannabis use in British Columbia. [PDF] Centre for Addictions Research of BC: Bulletin 2. Retrieved from http://carbc.ca/portals/0/propertyagent/558/files/19/carbcbulletin2.pdf.

Strang, H., Sherman, L. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., Woods, D., & Ariel, B. (2013, November 11). Restorative justice conferencing (RJC) using face-to-face meetings of offenders and victims: Effects on offender recidivism and victim satisfaction. A systematic review. Campbell Systematic Reviews. Retrieved from http://www.campbellcollaboration.org/lib/project/63/.

Wildeman, C. (2010). Paternal incarceration and children’s physically aggressive behaviours: Evidence from the fragile families and child wellbeing study. Social Forces, 89(1), 285-310.

Wortley, S. (2003). Hidden intersections: Research on race, crime, and criminal justice in Canada. Canadian Ethnic Studies, 35(3), 99-117.

van de Rakt, M., Murray, J., & Nieuwbeerta, P. (2012). The long-term effects of paternal imprisonment on criminal trajectories of children. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 49(1), 81-108.

Image Attributions

Figure 9.1.

Figure 9.4. Inside one of the prison buildings at Presidio Modelo by Friman (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Presidio-modelo2.JPG) used under CC BY SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/deed.en)

Figure 9.8. Dorchester Penitentiary. Image Courtesy of courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Figure 9._. Lizzie Borden (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Lizzie_borden.jpg) is in the public domain (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain)

Figure 9._. Cover page of 1550 edition of Machiavelli’s Il Principe and La Vita di Castruccio Castracani da Lucca by RJC (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Machiavelli_Principe_Cover_Page.jpg) is in the public domain (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain)

Figure 9.11. Cover scan of a Famous Crimes by Fox Features Syndicate (http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Famous_Crimes_54893.JPG) is in the public domain (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_domain)

Long Descriptions

| Type of Hate Crime | Number reported to Police |

|---|---|

| Race or Ethnicity | 690 |

| Religion | 315 |

| Sexual Orientation | 235 |

| Other | 80 |

| Unknown | 10 |

Solutions to Chapter Quiz

1 d, | 2 a, | 3 c | 4 b, | 5 a, | 6 a, | 7 a, | 8 b, | 9 a

[Return to Quiz]