7 Global Inequality

Learning Objectives

7.1 Global Stratification and Classification

- Describe global stratification.

- Understand how different classification systems have developed.

- Use terminology from Wallerstein’s world systems approach.

- Explain the World Bank’s classification of economies.

7.2. Global Wealth and Poverty

- Understand the differences between relative and absolute poverty.

- Describe the economic situation of some of the world’s most impoverished areas.

- Explain the cyclical impact of the consequences of poverty.

7.3. Theoretical Perspectives on Global Stratification

- Describe the modernization and dependency theory perspectives on global stratification.

Introduction to Global Inequality

A new millennium started in 2000. Just like we make New Year resolutions, some countries wanted to change the world in the new millennium. United Nations countries made Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). The MDGs aimed to eliminate extreme poverty around the world. Nearly 200 countries signed the goals.

The countries created eight categories of goals. They hoped to reach these targets by 2015:

- Eradicate extreme poverty and hunger

- Achieve universal primary education

- Promote gender equality and empower women

- Reduce child mortality

- Improve maternal health

- Combat HIV/AIDS, malaria, and other diseases

- Ensure environmental sustainability

- Develop a global partnership for development (United Nations, 2010)

By 2016, progress was made toward some MDGs, but little progress was made toward others.

Goals with progress:

- poverty

- education

- child mortality

- access to clean water (health)

Some nations made much progress in these goals, but others made very little.

Goals with less progress:

- Hunger and malnutrition increased from 2007 through 2009, undoing earlier achievements.

- Employment was also slow to increase

- HIV infection rates were not reduced. Infection rates continue to outpace the number of people getting treatment.

- Mortality and health care rates for mothers and infants also showed little advancement. (United Nations, 2010)

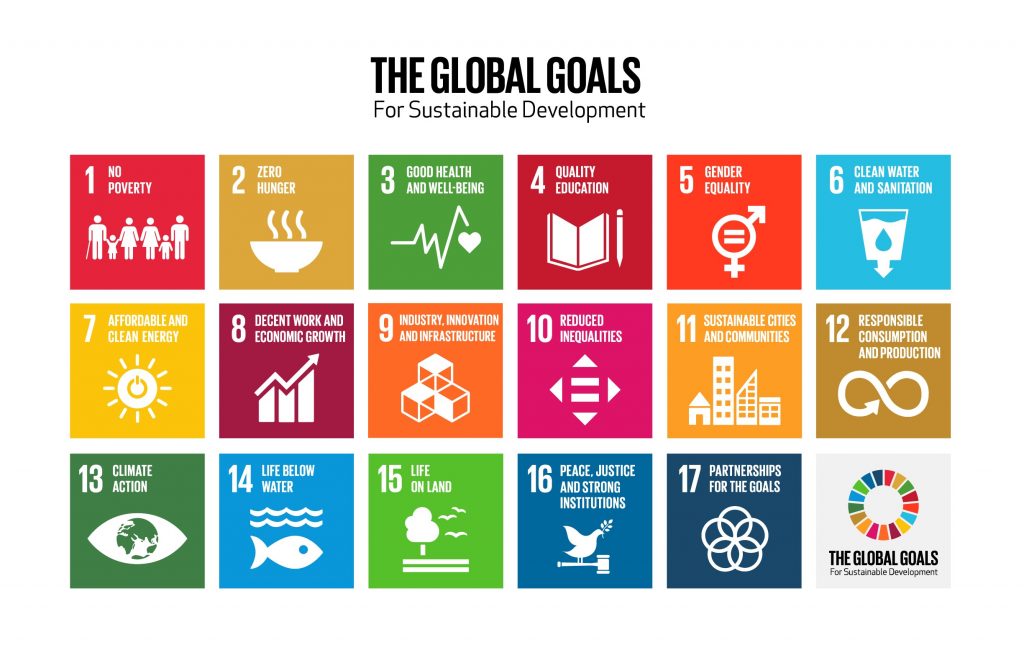

The United Nations continues to work for global equality, however. In 2016 the UN launched its 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development to build on progress made in the MDGs. The Agenda includes seventeen Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), described as “our shared vision of humanity and a social contract between the world’s leaders and the people. They are a to-do list for people and planet, and a blueprint for success.” (United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, 2016) You can follow the progress towards these goals on the United Nations’ website dedicated to the SDGs, https://www.globalgoals.org.

How have the world’s people have ended up in circumstances that require projects like the MDGs and SDGs? How did wealth become concentrated in some nations? What motivates companies to globalize? Is it fair for powerful countries to make rules that make it difficult for less-powerful nations to compete globally? Sociologists and historians investigate questions like these. This chapter provides background for understanding some of these issues.

7.1. Global Stratification and Classification

Just as North America’s wealth is increasingly concentrated among its richest citizens while the middle class slowly disappears, global inequality involves the concentration of resources in certain nations, significantly affecting the opportunities of individuals in poorer and less powerful countries.

Global Stratification

In Canada, stratification refers to the unequal distribution of resources among individuals, global stratification refers to this unequal distribution among nations. Global stratification refers to this unequal distribution of resources among nations. There are two dimensions to global stratification: gaps between nations and gaps within nations.

Economic inequality and social inequality are often related (Myrdal, 1970). For example, as the table below illustrates, people’s life expectancy depends heavily on where they happen to be born.

| Country | Infant Mortality Rate | Life Expectancy |

|---|---|---|

| Canada | 4.9 deaths per 1,000 live births | 81 years |

| Mexico | 17.2 deaths per 1,000 live births | 76 years |

| Democratic Republic of Congo | 78.4 deaths per 1,000 live births | 55 years |

Most of us are accustomed to thinking of global stratification as economic inequality. For example, we can compare China’s average worker’s wage to Canada’s average wage. Social inequality, however, is just as harmful as economic discrepancies. Prejudice and discrimination — whether against a certain race, ethnicity, religion, or the like — can create and aggravate conditions of economic equality, both within and between nations.

Think about the inequiality that existed for decades within the nation of South Africa. Apartheid was one of the most extreme cases of institutionalized and legal racism. Apartheid created social inequality that earned the world’s condemnation. Think also about Western disregard of the crisis in Darfur. Since few citizens of Western nations identified with the impoverished, non-white victims of the genocide, there was little pressure to provide aid.

Gender inequity is another global concern. Consider female genital mutilation. Nations that practice this female circumcision procedure defend it as a cultural tradition and argue that the West should not interfere. Other nations, however, condemn the practice and work to stop it.

Inequalities based on sexual orientation and gender identity exist around the world. According to Amnesty International, many crimes are committed against people who do not conform to traditional gender roles or sexual orientations. Legalized and culturally accepted forms of prejudice and discrimination exist everywhere. The prejudice and discrimination can restrict freedom and even endanger lives; for example, culturally sanctioned rape and state-sanctioned executions. (Amnesty International, 2012).

Global Classification

Our language can imply that less developed nations want to be like countries with postindustrial global power like the U.S. and Russia. Terms such as “developing” (non-industrialized) and “developed” (industrialized) imply that non-industrialized countries are inferior. These terms suggest that developing nations must improve to participate successfully in the global economy. Global economy is a label meaning that economic activity crosses national borders.

In fact, the earth couldn’t sustain life if every country consumed resources and polluted like Canada, Russia and the United States. Here is a history of how we talked about development.

Cold War Terminology

During the Cold War (1945–1980) the world was divided between capitalist and communist economic systems. We classified countries into first world, second world, and third world nations based on economic development and standard of living. Capitalist democracies such as the United States, Canada and Japan were part of the first world. The poorest, most undeveloped countries were referred to as the third world. The third world included most of sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America, and Asia. The second world was the socialist world or Soviet bloc: These countries were industrially developed but organized according to a state socialist or communist model.

During the Cold War, global inequality was described in terms of economic development. Along with developing and developed nations, the terms “less-developed nation” and “underdeveloped nation” were used. Modernization theory suggested that societies moved through natural stages of development: They progressed toward becoming developed societies (defined as stable, democratic, capitalist). Here is a summary of stages according to modernization theory:

- traditional society (based on simple agriculture with low productivity)

- industrial production, expansion of markets

- maturity (a modern industrialized economy, highly capitalized and technologically advanced)

- the age of mass-consumption (TVs, cars, refrigerators, etc.), and luxury goods, general prosperity, egalitarianism.

This was the era when we thought “developed nations” should provide foreign aid to the less-developed nations to raise their standard of living (that is, to be more like them).

Immanuel Wallerstein: World Systems Approach

Wallerstein’s (1979) world systems approach uses an economic and political basis to understand global inequality. Development and underdevelopment are not stages in a natural process of gradual modernization, but the product of power relations and colonialism. Wallerstein conceived the global economy as a complex historical system supporting an economic hierarchy. This hierarchy placed some nations in positions of power with many resources; Other nations were put in a state of economic subordination. Those in a state of subordination faced many obstacles.

Core nations are dominant countries, highly industrialized, technological, and urbanized. For example, Wallerstein says that the United States is an economic powerhouse that can support or deny support to important economic legislation. In that way the U.S. exerts control over aspects of the global economy and exploits other nations. Free trade agreements such as the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and United States Mexico Canada Agreement (USMCA) are examples of how a core nation tires to use its power to gain the most advantageous trade position.

Peripheral nations have little industrialization. Their industries are often built from the outdated castoffs of core nations. Their factories and means of production are owned by core nations. Their resources are exploited by core nations. They may have unstable government and inadequate social programs, and they become economically dependent on core nations for jobs and aid. Many countries are in this category. Check the label of your jeans or sweatshirt and see where it was made. Chances are it was a peripheral nation such as Guatemala, Bangladesh, Malaysia, or Colombia. Workers in these factories, which are owned or leased by global core nation companies, usually do not have the same privileges and rights as Canadian workers.

Semi-peripheral nations are in-between nations, not powerful enough to dictate policy and are used as major sources for raw material. They may have an expanding middle-class marketplace for core nations. They may also exploit peripheral nations. Mexico is an example. Mexico provides cheap agricultural labour to the United States and Canada and supplies goods to the North American market at a rate dictated by U.S. and Canadian consumers. However, Mexicans don’t have the protections offered to U.S. or Canadian workers.

World Bank Economic Classification by Income

The World Bank classifies economies by GNI or gross national income. Gross national income equals all goods and services plus net income earned outside the country by nationals. It also includes incomes from corporations headquartered in the country doing business out of the country. GNI is measured in U.S. dollars. GNI includes not only the value of goods and services inside the country, but also the value of income earned outside the country if it is earned by nationals. That means that multinational corporations that earn billions in offices and factories around the globe are considered part of a core nation’s GNI if they have headquarters in the core nations. Along with tracking the economy, the World Bank tracks demographics and environmental health to provide a picture of whether a nation is high income, middle income, or low income.

High-Income Nations

The World Bank defines high-income nations as having a GNI of at least $12,500 (USD) per capita. It separates out the OECD (Organization for Economic and Co-operative Development) countries, a group of 34 nations whose governments work together to promote economic growth and sustainability. According to the Work Bank (2011), in 2010, the average GNI of a high-income nation belonging to the OECD was $40,136 per capita; on average, 77% of the population in these nations was urban. OECD countries include Canada, the United States, Germany, and the United Kingdom (World Bank, 2011). In 2010, the average GNI of a high-income nation that did not belong to the OECD was $23,839 per capita. 83% of their population was, on average, urban. These countries include Saudi Arabia and Qatar (World Bank, 2011, 2018).

High-income countries face two major issues: capital flight and deindustrialization. Capital flight refers to the movement (flight) of capital from one nation to another, as when General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler close Canadian factories in Ontario and open factories in Mexico. Deindustrialization, a related issue, occurs because of capital flight. No new companies open to replace jobs lost to foreign nations. Global companies move their industrial processes to the places where they can get the most production with the least cost, including the costs for building infrastructure, training workers, shipping goods, and, of course, paying employee wages. As emerging economies create their own industrial zones, global companies see the opportunity for much lower costs. Those opportunities lead to businesses closing the factories that supply jobs to the middle-class in core nations and moving their industrial production to peripheral and semi-peripheral nations

Capital Flight, Outsourcing, and Jobs in Canada

Capital flight describes jobs and infrastructure moving from one nation to another. Look at the manufacturing industries in Ontario. Ontario was the traditional centre of manufacturing in Canada from the 19th century. At the turn of the 21st century, 18% of Ontario’s labour market was made up of manufacturing jobs in industries like automobile manufacturing, food processing, and steel production. At the end of 2013, only 11% of the labour force worked in manufacturing. Between 2000 and 2013, 290,000 manufacturing jobs were lost (Tiessen, 2014).

Often the value of the Canadian dollar compared to the American dollar is blamed for these job losses. Because of the high value of Canada’s oil exports, international investors can drive up the value of the Canadian dollar in a process referred to as Dutch disease, the relationship between an increase in the development of natural resources and a decline in manufacturing. Canadian-manufactured products become too expensive as a result. However, this is just another way of describing capital flight to locations that have cheaper manufacturing costs and cheaper labour. Since the introduction of the North American free trade agreements, the ending of the tariff system that protected branch plant manufacturing in Canada allowed U.S. companies to shift production to low-wage regions south of the border and in Mexico.

Capital flight also occurs when services (as opposed to manufacturing) are relocated. When you contact the tech support line for your cell phone or internet provider, you may have spoken to someone halfway across the globe. It might be the middle of the night in that country, yet these service providers pick up the line saying, “good morning,” as though they are in the next town over. They know everything about your phone or your modem, often using a remote server to log in to your home computer to accomplish what is needed. These are the workers of the 21st century. They are not on factory floors or in traditional sweatshops; they are educated, speak at least two languages, and usually have significant technology skills. They are skilled workers, but they are paid a fraction of what similar workers are paid in Canada. For Canadian and multinational companies, this makes sense. India and other semi-peripheral countries have emerging infrastructures and education systems to fill their needs, without core nation costs.

As services relocate, so do jobs. In Canada, unemployment is high. Many university-educated people can’t find work, and those with only a high school diploma have more obstacles. We have outsourced ourselves out of jobs. But before we complain, look at the culture of consumerism that Canadians embrace. A television that might have cost $2,000 a few years ago is now $450. That cost saving comes from somewhere. When Canadians seek the lowest possible price, shop at big box stores for the biggest discount they can get, and ignore other factors in exchange for low cost, they are building the market for outsourcing. And as the demand builds, the market will ensure it is met, often at the expense of the people who wanted that inexpensive television.

Middle-Income Nations

The World Bank defines lower middle-income countries as having a GNI that ranges from $1,006 to $3,975 per capita and upper middle-income countries as having a GNI ranging from $3,976 to $12,500 per capita. In 2010, the average GNI of an upper middle-income nation was $5,886 per capita with a population that was 57% urban. Brazil, Thailand, China, and Namibia are examples of middle-income nations (World Bank, 2011).

Perhaps the most important issue for middle-income nations is the problem of debt accumulation. Debt accumulation is the buildup of external debt, when countries borrow money from other nations to fund expansion or growth. Global economic uncertainty make repaying these debts (or even paying the interest) challenging, and nations find themselves in trouble. Such issues have plagued middle-income countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, as well as East Asian and Pacific nations (Dogruel and Dogruel, 2007). Even in the European Union, composed of more core nations than semi-peripheral nations, the semi-peripheral nations of Italy, Portugal, and Greece face increasing debt burdens. The economic downturns in these countries threaten the economy of the entire European Union.

Low-Income Nations

The World Bank defines low-income countries as nations having a GNI of $1,005 per capita or less in 2010. In 2010, the average GNI of a low-income nation was $528 and the average population was 796,261,360, with 28% located in urban areas. For example, Myanmar, Ethiopia, and Somalia are considered low-income countries. Low-income economies are primarily found in Asia and Africa, where most of the world’s population lives (World Bank, 2011).

Two major challenges these countries face: women are disproportionately affected by poverty (in a trend toward a global feminization of poverty) and much of the population lives in absolute poverty. Global feminization of poverty means that around the world, women bear a disproportionate percentage of the burden of poverty. More women than men live in poor conditions, receive inadequate health care, endure the most of malnutrition and inadequate drinking water, and so on. Throughout the 1990s, data showed that while overall poverty rates were rising, especially in peripheral nations, the rates of impoverishment increased nearly 20% more for women than for men (Mogadham, 2005).

Why is this happening? While many variables affect women’s poverty, research identifies three causes:

- The expansion of female-headed households

- The persistence and consequences of inequalities within households ( biases against women)

- The implementation of neoliberal economic policies around the world (Mogadham, 2005)

This means that within an impoverished household, women are more likely to go hungry than men; in agricultural aid programs, women are less likely to receive help than men; and often, women are left taking care of families with no male counterpart due to economic, social or political conditions.

7.2. Global Wealth and Poverty

What does it mean to be poor? Does it mean being a single support parent with two kids in Toronto, waiting for the next pay cheque to buy groceries? Does it mean living with almost no furniture in your apartment because your income does not allow for extras like beds or chairs? Or does it mean the distended bellies of the chronically malnourished in the peripheral nations of sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia?

Poverty has no single definition. You might feel poor if you can’t afford cable television or a car. When you see a fellow student with a new laptop or smartphone, you might feel that your ten-year-old desktop computer makes you poor. However, someone else might look your clothes or food and consider you rich.

Types of Poverty

Social scientists define global poverty in different ways, considering the complexities and the issues of relativism. Relative poverty is a state of living where people can afford necessities but are unable to meet their society’s average standard of living. They may be unable to participate in society in a meaningful way. A Canadian might feel “poor” if they do not have a car or money for a safety net should a family member become sick.

Unlike relative poverty, people who live in absolute poverty lack even the necessities: adequate food, clean water, safe housing, and access to health care. Absolute poverty is defined by the World Bank (2011) as living on less than a dollar a day. A shocking number of people — more than 88 million — live in absolute poverty. Close to 3 billion people live on less than $2.50 a day (Shah, 2011). If you were forced to live on $2.50 a day, how would you do it? What would you buy, and what could you do without? How would you manage the necessities — and how would you make up the gap between what you need to live and what you can afford?

Who Are the Impoverished?

Who is living in absolute poverty? Most of us would guess correctly that the richest countries typically have the fewest people. Compare Canada and India. Canada has a relatively small population but owns a large amount of the world’s wealth. India has a large population and less accumulated wealth (although that country’s wealth increases).

The poorest people in the world are women in peripheral and semi-peripheral nations. For women, the rate of poverty is worsened by the pressure on their time. Studies show that women in poverty, who are responsible for all family comforts as well as any earnings they can make, have less leisure time. While men and women may have the same rate of economic poverty, women are suffering more in terms of overall well-being (Buvinić, 1997). It is harder for females to get credit to expand businesses, to take the time to learn a new skill, or to spend extra hours improving their craft to be able to earn at a higher rate.

Africa

Most of the poor countries in the world are in Africa. Not all African nations are poor, however. Countries like South Africa and Egypt have much lower rates of poverty than Angola and Ethiopia, for instance. Overall, African income levels have been dropping relative to the rest of the world, meaning that Africa is getting relatively poorer. Climate conditions like drought bring starvation to some regions and make the problem worse. Wars are fought over resources. Many wars and resource depletion are the legacy of centuries of colonialism and continued exploitation by economically powerful nations.

Why is Africa—a resource rich continent–so poor? The biggest reason: Many natural resources were long ago taken or destroyed by colonial countries and their wars. Much of the continent’s poverty is due to destruction of land that can be farmed (arable land). Centuries of struggle over land and resources left much arable land ruined. Climate change and deforestation affect many areas. Some countries with inadequate rainfall don’t have irrigation infrastructure.

In some African countries, civil wars and poor government happened because artificial borders were made by colonial countries. Often puppet leaders were put in charge by colonial power, too.

Consider Rwanda. Two ethnic groups lived together with their own system of hierarchy and management until Belgians took control of the country in 1915. The Belgian occupiers rigidly defined members of the population into two unequal ethnic groups. Before the Belgians, members of the Tutsi group held positions of power. Belgian interference led to the Hutu’s seizing power during a 1960s revolt. This eventually led to a repressive government and genocide against Tutsis. Hundreds of thousands of Rwandans were killed or fled their country. (U.S. Department of State, 2011c).

Since the 1960s, most African countries regained the power to govern themselves; however, many countries continue to struggle to overcome the past interference. (World Poverty, 2012a).

Asia

While most the world’s poorest countries are in Africa, most of the world’s poorest people are in Asia. (Why is that?) Like Africa, Asia finds itself with unequal distribution of wealth. Japan, South Korea, Indonesia hold much more wealth than Laos and Cambodia, for example. In fact, most poverty is concentrated in South Asia. Centuries of colonialism also affected economic development in many Asian countries. Another cause of poverty in Asia is the pressure that the size of the population puts on its resources. In fact, many believe that China’s success in recent times has much to do with its harsh population control rules.

According to the U.S. State Department, China’s market-oriented reforms have also contributed to significant reduction of poverty and rapidly increasing in income levels (U.S. Department of State, 2011b). However, every part of Asia has felt the recent global recessions, from the poorest countries whose aid packages were hit, to the more industrialized ones whose own industries slowed down. (World Poverty, 2012b).

Latin America

Poverty rates in some Latin American countries like Mexico have improved recently, partly because of investment in education. But other countries continue to struggle. Although there is a large amount of foreign investment in this part of the world, it tends to be higher-risk speculative investment. The instability of these investments means that the region has been unable to benefit, especially when mixed with high interest rates for aid loans. Further, internal political struggles, illegal drug trafficking, and corrupt governments have added to the pressure (World Poverty, 2012c). This is another area of the world impacted by centuries of colonialism.

The True Cost of a T-Shirt

Most of us do not pay too much attention to where our favourite products are made. And certainly when you are shopping for a cheap T-shirt, you probably do not turn over the label, check who produced the item, and then research whether or not the company has fair labour practices. In fact it can be very difficult to discover where exactly the items we use everyday have come from. Nevertheless, the purchase of a T-shirt involves us in a series of social relationships that ties us to the lives and working conditions of people around the world.

On April 24, 2013, the Rana Plaza building in Dhaka, Bangladesh, collapsed killing 1,129 garment workers. The building, like 90% of Dhaka’s 4,000 garment factories, was structurally unsound. Garment workers in Bangladesh work under unsafe conditions for as little as $38 a month so that North American consumers can purchase T-shirts in the fashionable colours of the season for as little as $5. The workers at Rana Plaza were in fact making clothes for the Joe Fresh label — the signature popular Loblaw brand — when the building collapsed. Having been put on the defensive for their overseas sweatshop practices, companies like Loblaw have pledged to improve working conditions in their suppliers’ factories, but compliance has proven difficult to ensure because of the increasingly complex web of globalized production (MacKinnon and Strauss, 2013).

At one time, the garment industry was important in Canada, centred on Spadina Avenue in Toronto and Chabanel Street in Montreal. But over the last two decades of globalization, Canadian consumers have become increasingly tied through popular retail chains to a complex network of outsourced garment production that stretches from China, through Southeast Asia, to Bangladesh and Sri Lanka. The early 1990s saw the economic opening of China when suddenly millions of workers were available to produce and manufacture consumer items for Westerners at a fraction of the cost of Western production. Manufacturing that used to take place in Canada moved overseas. Over the ensuing years, the Chinese began to outsource production to regions with even cheaper labour: Vietnam, Cambodia, Sri Lanka, and Bangladesh. The outsourcing was outsourced. The result is that when a store like Loblaw places an order, it usually works through agents who in turn source and negotiate the price of materials and production from competing locales around the globe.

Most of the T-shirts that we wear in Canada today begin their life in the cotton fields of arid west China, which owe their scale and efficiency to the collectivization projects of centralized state socialism. However, as the cost of Chinese labour has incrementally increased since the 1990s, the Chinese have moved into the role of connecting Western retailers and designers with production centres elsewhere. In a global division of labour, if agents organize the sourcing, production chain and logistics, Western retailers can focus their skill and effort on retail marketing. It was in this context that Bangladesh went from having a few dozen garment factories to several thousand. The garment industry now accounts for 80% of Bangladesh’s export earnings. Unfortunately, although there are legal safety regulations and inspections in Bangladesh, the rapid expansion of the industry has exceeded the ability of underfunded state agencies to enforce them.

The globalization of production makes it difficult to follow the links between the purchasing of a T-shirt in a Canadian store and the chain of agents, garment workers, shippers, and agricultural workers whose labour has gone into producing it and getting it to the store. Our lives are tied to this chain each time we wear a T-shirt, yet the history of its production and the lives it has touched are more or less invisible to us. It becomes even more difficult to do something about the working conditions of those global workers when even the retail stores are uncertain about where the shirts come form. There is no international agency that can enforce compliance with safety or working standards. Why do you think worker safety standards and factory building inspections have to be imposed by government regulations rather than being simply an integral part of the production process? Why does it seem normal that the issue of worker safety in garment factories is set up in this way? Why does this make it difficult to resolve or address the issue?

The fair trade movement has pushed back against the hyper-exploitation of global workers and forced stores like Loblaw to try to address the unsafe conditions in garment factories like Rana Plaza. Organizations like the Better Factories Cambodia program inspect garment production regularly in Cambodia, enabling stores like Mountain Equipment Co-op to purchase reports on the factory chains it relies on. After the Rana Plaza disaster, Loblaw signed an Accord of Fire and Building Safety in Bangladesh to try to ensure safety compliance of their suppliers. However the bigger problem seems to originate with our desire to be able to purchase a T-shirt for $5 in the first place.

Consequences of Poverty

The consequences of poverty are often also causes of poverty. Poor people experience inadequate health care, limited education, and inaccessible birth control. Those born into these conditions are incredibly challenged in their efforts to break this cycle of disadvantage.

Sociologists Neckerman and Torche (2007) divided the consequences into three areas. The first, “the sedimentation of global inequality,” means that once poverty becomes entrenched in an area, it is very difficult to reverse. Poverty exists in a cycle where the consequences and causes are interconnected. The second consequence of poverty is its effect on physical and mental health. Poor people face physical health challenges, including malnutrition and high infant and maternal mortality rates. Mental health is also negatively affected by the emotional stresses of poverty. Again, these effects of poverty become more entrenched as time goes on. Neckerman and Torche’s third consequence of poverty is the prevalence of crime. Cross-nationally, crime rates, particularly violent crime, are higher in countries with higher levels of income inequality (Fajnzylber, Lederman, and Loayza 2002).

Slavery

While most of us are accustomed to thinking of slavery in terms of pre–Civil War America, modern-day slavery goes hand in hand with global inequality. In short, slavery refers to any time people are sold, treated as property, or forced to work for little or no pay. Just as in pre–Civil War America, these humans are at the mercy of their employers. Chattel slavery, the form of slavery practised in the pre–Civil War American South, is when one person owns another as property. Child slavery, which may include child prostitution, is a form of chattel slavery. Debt bondage, or bonded labour, involves the poor pledging themselves as servants in exchange for the cost of basic necessities like transportation, room, and board. In this scenario, people are paid less than they are charged for room and board. When travel is involved, people can arrive in debt for their travel expenses and be unable to work their way free, since their wages do not allow them to ever get ahead.

The global watchdog group Anti-Slavery International recognizes other forms of slavery: human trafficking (where people are moved away from their communities and forced to work against their will), child domestic work and child labour, and certain forms of servile marriage, in which women are little more than chattel slaves (Anti-Slavery International, 2012).

7.3. Theoretical Perspectives on Global Stratification

As with any social issue, global or otherwise, there are a variety of theories that scholars develop to study the topic. The two most widely applied perspectives on global stratification are modernization theory and dependency theory.

Modernization Theory

According to modernization theory, low-income countries are affected by their lack of industrialization and can improve their global economic standing through:

- An adjustment of cultural values and attitudes to work

- Industrialization and other forms of economic growth (Armer and Katsillis, 2010)

Critics point out the inherent ethnocentric bias of this theory. It supposes all countries have the same resources and are capable of following the same path. In addition, it assumes that the goal of all countries is to be as “developed” as possible (i.e., like the model of capitalist democracies provided by Canada or the United States). There is no room within this theory for the possibility that industrialization and technology are not the best goals.

There is, of course, some basis for this assumption. Data show that core nations tend to have lower maternal and child mortality rates, longer lifespans, and less absolute poverty. It is also true that in the poorest countries, millions of people die from the lack of clean drinking water and sanitation facilities, which are benefits most of us take for granted. At the same time, the issue is more complex than the numbers might suggest. Cultural equality, history, community, and local traditions are all at risk as modernization pushes into peripheral countries. The challenge, then, is to allow the benefits of modernization while maintaining a cultural sensitivity to what already exists.

Dependency Theory

Dependency theory was created in part as a response to the Western-centric mindset of modernization theory. It states that global inequality is primarily caused by core nations (or high-income nations) exploiting semi-peripheral and peripheral nations (or middle-income and low-income nations), creating a cycle of dependence (Hendricks, 2010). In the period of colonialism, core or metropolis nations created the conditions for the underdevelopment of peripheral or hinterland nations through a metropolis-hinterland relationship. The resources of the hinterlands were shipped to the metropolises where they were converted into manufactured goods and shipped back for consumption in the hinterlands. The hinterlands were used as the source of cheap resources and were unable to develop competitive manufacturing sectors of their own.

Dependency theory states that as long as peripheral nations are dependent on core nations for economic stimulus and access to a larger piece of the global economy, they will never achieve stable and consistent economic growth. Further, the theory states that since core nations, as well as the World Bank, choose which countries to make loans to, and for what they will loan funds, they are creating highly segmented labour markets that are built to benefit the dominant market countries.

At first glance, it seems this theory ignores the formerly low-income nations that are now considered middle-income nations and are on their way to becoming high-income nations and major players in the global economy, such as China. But some dependency theorists would state that it is in the best interests of core nations to ensure the long-term usefulness of their peripheral and semi-peripheral partners. Following that theory, sociologists have found that entities are more likely to outsource a significant portion of a company’s work if they are the dominant player in the equation; in other words, companies want to see their partner countries healthy enough to provide work, but not so healthy as to establish a threat (Caniels, Roeleveld, and Roeleveld, 2009).

Globalization Theory

Globalization theory focuses less on the relationship between dependent and core nations, and more on the international flow of capital investment in an increasingly interconnected world market. Since the 1970s, capital accumulates less in national economies. Rather, as in the example of the garment industry, capital circulates on a global scale, leading to global inequalities both between nations and within nations. The production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services are integrated on a worldwide basis. Effectively, we no longer live and act in national states.

The core pieces of the “globalization project” (McMichael, 2012) — the project to transform the world into one market — are

- imposition of open “free” markets across national borders

- deregulation of trade and investment

- privatization of public goods and services.

Development has been redefined from nationally managed economic growth to “participation in the world market” (World bank, cited in McMichael, 2012, pp. 112-113). The global economy, not modernized national economies, emerges as the site of development. Within this model, the world and its resources are reorganized and managed based on free trade of goods and services and the free circulation of capital. This is all managed by democratically unaccountable political and economic elite organizations like the G20, the WTO (World Trade Organization), GATT (General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs), the World Bank and IMF (International Monetary Fund), and international measures used to liberalize the global economy.

According to globalization theory, globalization redistributes wealth and poverty on a global scale. Outsourcing shifts production to low-wage areas, displacement leads to higher unemployment rates in the traditionally wealthy global north, people migrate from rural to urban areas and “slum cities” and from poor countries to rich countries. Large numbers of workers simply become redundant to global production and turn to informal, casual labour. The anti-globalization movement has emerged as a counter-movement for an alternative, non-corporate world based on environmental sustainability, food sovereignty, labour rights, and democratic accountability.

Some populist leaders like Donald Trump have been accused of “hijacking” anti-globalization feelings for votes while they continue to support accumulation of wealth by capitalist elites and exploitation of the world’s workers.

Factory Girls

Would you like to know more about global inequality, and modernization and dependency theories.?

The book Factory Girls: From Village to City in Changing China, by Leslie T. Chang, provides this opportunity. Chang follows two young women (Min and Chunming) who are employed at a handbag plant. They help manufacture fashionable purses and bags for the global market. As part of the growing population of young people who are leaving behind the homesteads and farms of rural China, these female factory workers enter city life to pursue an income much higher than they could have earned back home.

Chang’s study is based in a city you may not have heard of, Dongguan. Dongguan produces one-third of all shoes on the planet (Nike and Reebok are major manufacturers here) and 30% of the world’s computer disk drives, in addition to a wide range of clothing (Chang, 2008).

Chang focused less on this global market and was more concerned with its effect on these two women. Chang examines the daily lives and interactions of Min and Chunming — their workplace friendships, family relations, gadgets, and goods — in this evolving global space where young women can leave tradition behind and shape their own futures. Change discovers that the women are hyper-exploited, but are also freed from the rural, Confucian, traditional culture. This allows them unprecedented personal freedoms. They go from the traditional family affiliations and narrow options of the past to life in a “perpetual present.” Friendships are fleeting and fragile, forms of life are improvised and sketchy, and everything they do is marked by the goals of upward mobility, resolute individualism, and an obsession with prosperity. Life for the women factory workers in Dongguan is an adventure, compared to their fate in rural village life, but one characterized by grueling work, insecurity, isolation, and loneliness. Chang writes, “Dongguan was a place without memory.”

Chapter Summary

Global Stratification and Classification

Stratification refers to the gaps in resources both between nations and within nations. While economic equality is of great concern, so is social equality, like the discrimination stemming from race, ethnicity, gender, religion, and/or sexual orientation. While global inequality is nothing new, several factors, like the global marketplace and the pace of information sharing, make it more relevant than ever. Researchers try to understand global inequality by classifying it according to factors such as how industrialized a nation is, whether it serves as a means of production or as an owner, and what income it produces.

Global Wealth and Poverty

When looking at the world’s poor, we first have to define the difference between relative poverty, absolute poverty, and subjective poverty. While those in relative poverty might not have enough to live at their country’s standard of living, those in absolute poverty do not have, or barely have, basic necessities such as food. Subjective poverty has more to do with one’s perception of one’s situation. North America and Europe are home to fewer of the world’s poor than Africa, which has highest number of poor countries, or Asia, which has the most people living in poverty. Poverty has numerous negative consequences, from increased crime rates to a detrimental impact on physical and mental health.

Theoretical Perspectives on Global Stratification

Modernization theory, dependency theory, and globalization theory are three of the most common lenses sociologists use when looking at the issues of global inequality. Modernization theory posits that countries go through evolutionary stages and that industrialization and improved technology are the keys to forward movement. Dependency theory sees modernization theory as Eurocentric and patronizing. With this theory, global inequality is the result of core nations creating a cycle of dependence by exploiting resources and labour in peripheral and semi-peripheral countries. Globalization theory argues that the division between the wealthy and the poor is now organized in the context of a single, integrated global economy rather than between core and peripheral nations.

Key Terms

absolute poverty: The state where one is barely able, or unable, to afford basic necessities.

anti-globalization movement: A global counter-movement based on principles of environmental sustainability, food sovereignty, labour rights, and democratic accountability that challenges the corporate model of globalization.

capital flight: The movement (flight) of capital from one nation to another, via jobs and resources.

chattel slavery: A form of slavery in which one person owns another.

core nations: Dominant capitalist countries.

debt accumulation: The buildup of external debt, wherein countries borrow money from other nations to fund their expansion or growth goals.

debt bondage: When people pledge themselves as servants in exchange for money or passage. They are subsequently paid too little to regain their freedom.

deindustrialization: The loss of industrial production, usually to peripheral and semi-peripheral nations where the costs are lower.

dependency theory: Theory stating that global inequity is due to the exploitation of peripheral and semi-peripheral nations by core nations.

first world: A term from the Cold War era that is used to describe industrialized capitalist democracies.

global inequality: The concentration of resources in core nations and in the hands of a wealthy minority.

global stratification: The unequal distribution of resources between countries.

gross national income (GNI): The income of a nation calculated based on goods and services produced, plus income earned by citizens and corporations headquartered in that country.

metropolis-hinterland relationship: The relationship between nations when resources of the hinterlands are shipped to the metropolises where they are converted into manufactured goods and shipped back to the hinterlands for consumption.

modernization theory: A theory that low-income countries can improve their global economic standing by industrialization of infrastructure and a shift in cultural attitudes toward work.

peripheral nations: Nations on the fringes of the global economy, dominated by core nations, with very little industrialization.

relative poverty: The state of poverty where one is unable to live the lifestyle of the average person in the country.

second world: A term from the Cold War era that describes nations with moderate economies and standards of living.

semi-peripheral nations: In-between nations, not powerful enough to dictate policy but acting as a major source of raw materials and providing an expanding middle-class marketplace.

third world: A term from the Cold War era that refers to poor, nonindustrialized countries.

Chapter Quiz

- France might be classified as which kind of nation?

- Global

- Core

- Semi-peripheral

- Peripheral

- In the past, Canada manufactured clothes. Many clothing corporations have shut down their Canadian factories and relocated to China. This is an example of ________.

- Conflict theory

- OECD

- Global inequality

- Capital fligh

- Slavery in the pre–Civil War American South most closely resembled _________.

- Chattel slavery

- Debt bondage

- Relative poverty

- Peonage

- Maya is a 12-year-old girl living in Thailand. She is homeless and often does not know where she will sleep or when she will eat. We might say that Maya lives in _________ poverty.

- Subjective

- Absolute

- Relative

- Global

- Mike, a college student, rents a studio apartment. He cannot afford a television and lives on cheap groceries like dried beans and ramen noodles. Since he does not have a regular job, he does not own a car. Mike is living in _________.

- Global poverty

- Absolute poverty

- Subjective poverty

- Relative poverty

- In a B.C. town, a mining company owns all the stores and most of the houses. It sells goods to the workers at inflated prices, offers house rentals for twice what a mortgage would be, and makes sure to always pay the workers less than they need to cover food and rent. Once the workers are in debt, they have no choice but to continue working for the company, since their skills will not transfer to a new position. This most closely resembles ___________.

- Child slavery

- Chattel slavery

- Debt slavery

- Servile marriage

- One flaw in dependency theory is the unwillingness to recognize ___________.

- That previously low-income nations such as China have successfully developed their economies and can no longer be classified as dependent on core nations

- That previously high-income nations such as China have been economically overpowered by low-income nations entering the global marketplace

- That countries such as China are growing more dependent on core nations

- That countries such as China do not necessarily want to be more like core nations

- One flaw in modernization theory is the unwillingness to recognize ____________.

- That semi-peripheral nations are incapable of industrializing

- That peripheral nations prevent semi-peripheral nations from entering the global market

- Its inherent ethnocentric bias

- The importance of semi-peripheral nations industrializing

- If a historian says that nations evolve toward more advanced technology and more complex industry as their citizens learn cultural values that celebrate hard work and success, she is using _________________ theory to study the global economy.

- Modernization theory

- Dependency theory

- Globalization theory

- Evolutionary dependency theory

- If a historian says that corporate interests dominate the global economy by creating global trade agreements and eliminating international tariffs that will favour the ability of capital to invest in low wage regions, he or she is a ____________.

- Dependency theorist

- Globalization theorist

- Modernization theorist

- Symbolic interactionist

- Dependency theorists explain global inequality and global stratification by focusing on the way that ____________.

- Core nations and peripheral nations exploit semi-peripheral nations

- Semi-peripheral nations exploit core nations

- Peripheral nations exploit core nations

- Core nations exploit peripheral nations

Short Answer

7.1. Global Stratification and Classification

-

Why do you think some researchers believe that Cold War terminology is objectionable? (“first world” etc.)

-

Give an example of the feminization of poverty in core nations. How is it the same or different in peripheral nations?

-

Imagine you are studying global inequality by looking at child labour manufacturing Barbie dolls in China. What do you focus on? How will you find this information? What theoretical perspective might you use?

7.2. Global Wealth and Poverty

Go to your campus bookstore. Find out who manufactures apparel and novelty items with your school’s insignias. In what countries are these produced? Does your school adhere to any principles of fair trade?

7.3. Theoretical Perspectives on Global Stratification

-

There is much criticism that modernization theory is Eurocentric. Do you think dependency theory and globalization theory are also biased? Why or why not?

-

Compare and contrast modernization theory, dependency theory, and globalization theory. Which do you think is more useful for explaining global inequality? Explain, using examples. You may want ot use a table for your comparison.

Further Research

7.2. Global Wealth and Poverty

Students often think that Canada is immune to the atrocity of human trafficking. Check out the following link to learn more about trafficking in Canada: http://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/rsrcs/pblctns/ntnl-ctn-pln-cmbt/index-eng.aspx; You can also check out the Canadian Women’s Foundation’s efforts to end sex trafficking: http://www.canadianwomen.org/trafficking

7.3. Theoretical Perspectives on Global Stratification

For more information about global affairs, check the Munk School of Global Affairs website: http://munkschool.utoronto.ca/

Go to Naomi Klein’s website for more information about the anti-globalization movement: http://www.naomiklein.org/main

References

7. Introduction to Global Inequality

United Nations Development Programme. (2010). “Millennium Development Goals.” Retrieved December 29, 2011 (http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/bkgd.shtml).

7.1. Global Stratification and Classification

Amnesty International. (2012). “Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity.” Retrieved January 3, 2012 (http://www.amnesty.org/en/sexual-orientation-and-gender-identity).

Castells, Manuel. (1998). End of Millennium. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Central Intelligence Agency. (2012). The world factbook. Central Intelligence Agency Library. Retrieved January 5, 2012, from https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/wfbExt/region_noa.html.

Dogruel, Fatma and A.Suut Dogruel. (2007). Foreign debt dynamics in middle income countries. Paper presented January 4, 2007 at Middle East Economic Association Meeting. Allied Social Science Associations, Chicago, IL.

Moghadam, Valentine M. (2005). The Feminization of poverty and women’s human rights. Gender Equality and Development Section, UNESCO, July. Paris, France.

Myrdal, Gunnar. (1970). The challenge of world poverty: A world anti-poverty program in outline. New York: Pantheon.

Rustow, Walt. (1960). The stages of economic growth: A non-communist manifesto. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tiessen, Kaylie. (2014, March). Seismic shift: Ontario’s changing labour market [PDF] Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. Retrieved April 9, 2014, from https://www.policyalternatives.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/publications/Ontario%20Office/2014/03/Seismic%20ShiftFINAL.pdf.

Wallerstein, Immanuel. (1979). The capitalist world economy. Cambridge, England: Cambridge World Press.

World Bank. (2011). Poverty and equity data. Retrieved December 29, 2011, from http://povertydata.worldbank.org/poverty/home.

7.2. Global Wealth and Poverty

Anti-Slavery International. (2012). What is modern slavery? Retrieved January 1, 2012, from http://www.antislavery.org/english/slavery_today/what_is_modern_slavery.aspx.

Barta, Patrick. (2009, March 14). The rise of the underground. Wall Street Journal. Retrieved January 1, 2012, from http://online.wsj.com/article/SB123698646833925567.html.

Buvinić, M. (1997). Women in poverty: A new global underclass. Foreign Policy, Fall (108):1–7.

Chen, Martha. (2001). Women in the informal sector: A global picture, the global movement. The SAIS Review 21:71–82.

Fajnzylber, Pablo, Daniel Lederman, and Norman Loayza. (2002). Inequality and violent crime. Journal of Law and Economics, 45:1–40.

Mackinnon, Mark and Marina Strauss. (2013, October 12). The true cost of a t-shirt [B1]. Toronto Globe and Mail. Retrieved April 8, 2014, from http://www.theglobeandmail.com/report-on-business/spinning-tragedy-the-true-cost-of-a-t-shirt/article14849193/

Neckerman, Kathryn and Florencia Torche. (2007). Inequality: Causes and consequences. Annual Review of Sociology, 33:335–357.

Schneider, F. and D.H. Enste. (2000). Shadow economies: size, causes, and consequences. Journal of Economic Literature, 38 (1): 77-114.

Shah, Anup. (2011). Poverty around the world. Global Issues [website]. Retrieved January 17, 2012, from http://www.globalissues.org/print/article/4.

U.S. Department of State. (2011a). Background note: Argentina. Retrieved January 3, 2012, from http://www.state.gov/r/pa/ei/bgn/26516.htm.

U.S. Department of State. (2011b). Background note: China. Retrieved January 3, 2012, from http://www.state.gov/r/pa/ei/bgn/18902.htm#econ.

U.S. Department of State. (2011c). Background note: Rwanda. Retrieved January 3, 2012, from http://www.state.gov/r/pa/ei/bgn/2861.htm#econ.

USAS. (2009, August). Mission, vision and organizing philosophy. Retrieved January 2, 2012, from http://usas.org.

World Bank. (2011). Data. Retrieved December 22, 2011, from http://www.worldbank.org.

World Poverty. (2012a). Poverty in Africa, famine and disease. Retrieved January 2, 2012, from http://world-poverty.org/povertyinafrica.aspx.

World Poverty. (2012b). Poverty in Asia, caste and progress. Retrieved January 2, 2012, from http://world-poverty.org/povertyinasia.aspx.

World Poverty. (2012c). Poverty in Latin America, foreign aid debt burdens. Retrieved January 2, 2012, from http://world-poverty.org/povertyinlatinamerica.aspx.

7.3. Theoretical Perspectives on Global Stratification

Armer, J. Michael and John Katsillis. (2010). Modernization theory. In E.F. Borgatta (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Sociology. Retrieved January 5, 2012, from http://edu.learnsoc.org/Chapters/3%20theories%20of%20sociology/11%20modernization%20theory.htm.

Caniels, Marjolein, C.J. Roeleveld, and Adriaan Roeleveld. (2009). Power and dependence perspectives on outsourcing decisions. European Management Journal, 27:402–417. Retrieved January 4, 2012, from http://ou-nl.academia.edu/MarjoleinCaniels/Papers/645947/Power_and_dependence_perspectives_on_outsourcing_decisions.

Chang, Leslie T. (2008). Factory girls: From village to city in changing China. New York: Random House.

Hendricks, John. (2010). Dependency theory. In E.F Borgatta (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Sociology. Retrieved January 5, 2012, from http://edu.learnsoc.org/Chapters/3%20theories%20of%20sociology/5%20dependency%20theory.htm.

McMichael, Philip. (2012). Development and Change. L.A.: Sage.

Image Attributions

Figure 7.2. Eve of Destruction by Rick Harris (https://www.flickr.com/photos/37153080@N00/62624493/) use under CC BY SA 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/)

Long Descriptions

Figure 7.1:

Eradicate extreme poverty and hunger.

Achieve universal primary education.

Promote gender equality and empower women.

Reduce child mortality.

Improve maternal health.

Combat HIV/AIDS, malaria, and other diseases.

Ensure environmental sustainability.

Develop a global partnership for development.

Solutions to Chapter Quiz

1 b, | 2 a, | 3 d, | 4 b, | 5 d, | 6 a, | 7 b, | 8 d, | 9 b, | 10 c, | 11 a, |

12 c, | 13 a, | 14 b, | 15 d

[Return to Quiz]