42 Avoiding Confirmation Bias in Searches

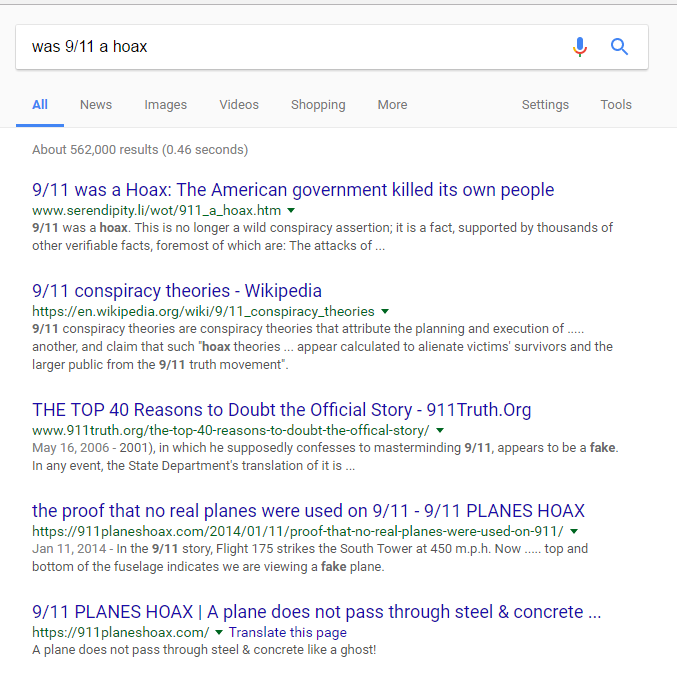

Was 9/11 a hoax? Let’s find out. We type in ‘was 9/11 a hoax’ and we get:

Well, look at that. Not only the top result says that the attack on 9/11 was faked–the top five results do. To the untrained eye it looks like the press has been hiding something from you.

But of course the 9/11 attacks were not faked. So why does Google return these results?

The main reason here is the term. The term “hoax” is applied to the 9/11 attacks primarily on conspiracy sites. So when Google looks for clusters on that term (and links to documents containing that term), it finds that conspiracy sites rank highly.

Think about it: reputable physics journals, policy magazines, and national newspapers are not likely to run headlines asking if the attacks were a hoax. But conspiracy sites are.

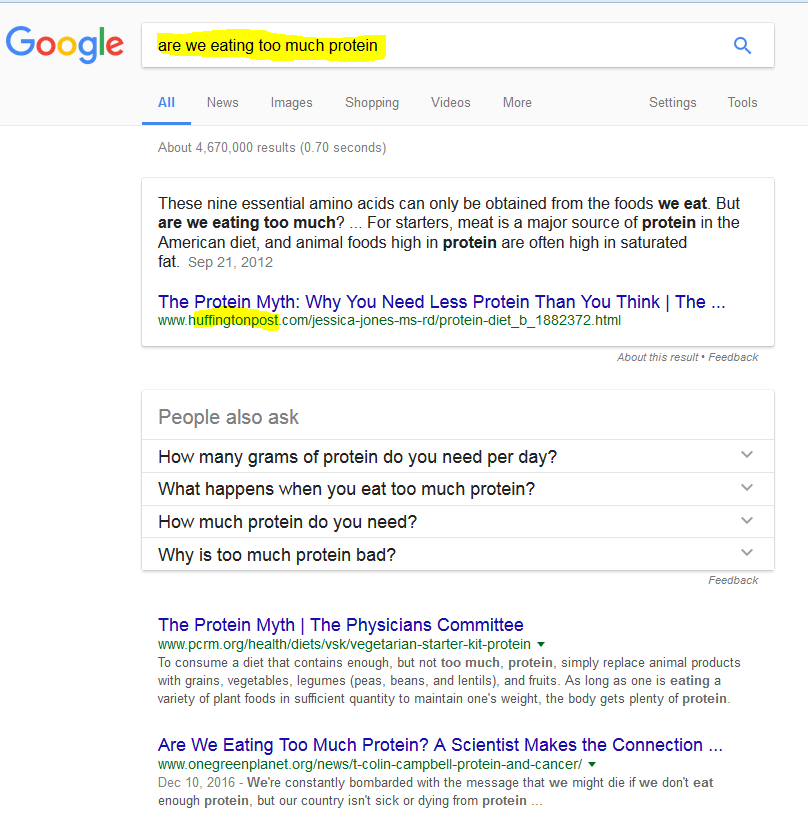

The same holds true even for more benign searches. The question, “Are we eating too much protein” has Google return a panel from the Huffington Post (now HuffPost) and a website from a vegan advocacy group.

To avoid confirmation bias in searches:

- Avoid asking questions that imply a certain answer. If I ask “Did the Holocaust happen?,” for example, I am implying that it is likely that the Holocaust was faked. If you want information on the Holocaust, sometimes it’s better just to start with a simple noun search, e.g. “Holocaust,” and read summaries that show how we know what happened.

- Avoid using terms that imply a certain answer. As an example, if you query “Women 72 cents on the dollar” you’ll likely get articles that tell you women make 72 cents on the dollar. But if you search for “Women 80 cents on the dollar” you’ll get articles that say women make 80 cents on the dollar. Searching for general articles on the “wage gap” might be a better choice.

- Avoid culturally loaded terms. As an example, the term “black-on-white crime” is a term used by white supremacist groups, but is not a term generally used by sociologists. As such, if you put that term into the Google search bar, you are going to get some sites that will carry the perspective of white supremacist sites, and be poor sources of serious sociological analysis.

- Plan to reformulate. Think carefully about what constitutes an authoritative source before you search. Once you search you’ll find you have an irrepressible urge to click into the top results. If you can, think of what sorts of sources and information you would like to see in the results before you search. If you don’t see those in the results, fight the impulse to click on forward, and reformulate your search.

- Scan results for better terms. Maybe your first question about whether the Holocaust happened turned up a poor result set in general but did pop up a Wikipedia article on Holocaust denialism. Use that term to make a better search for what you actually want to know.