11 Tracking the Source of Viral Content

In our previous examples, it has not been too difficult to trace the source of the information or claim. The Blaze story, clearly links to the Daily Dot piece so that anyone reading their summary is one click away from confirming it with the source. The New York Times makes it apparent that the syndicated content is from the Associated Press and Reuters, so checking the credibility of the sources is fairly simple.

This is good internet citizenship. Articles on the web that re-purpose other information or artifacts should state their sources, and, if appropriate, link to them. This matters to creators, because they deserve credit for their work. It also matters to readers who need to check the credibility of the original sources.

Unfortunately, some people on the web are not good internet citizens. This is particularly true with material that spreads quickly as hundreds or thousands of people share it – so-called “viral” content.

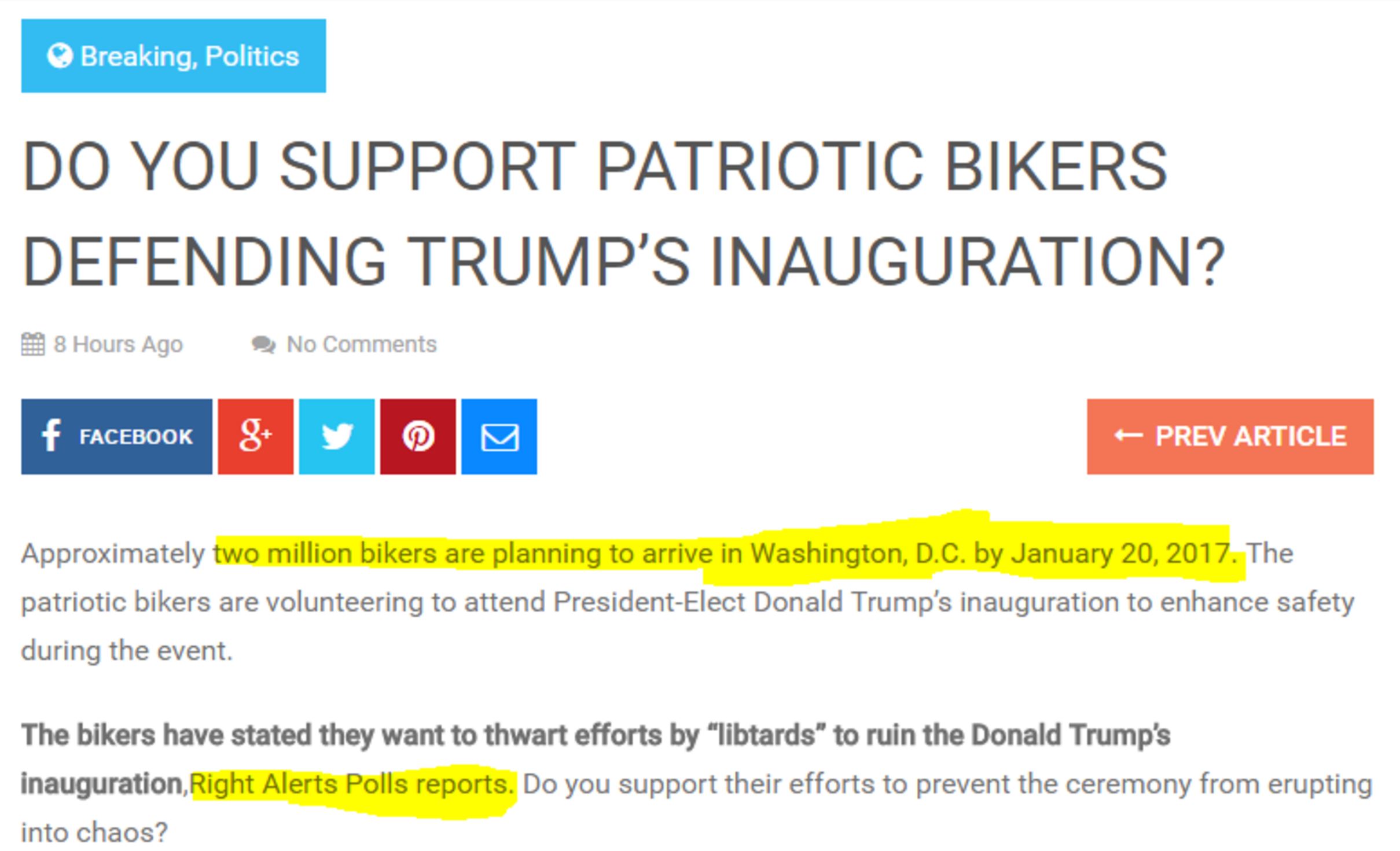

When that type of information travels around a network, people often fail to link it to sources, or they hide the sources altogether. For example, it was claimed that two million bikers were going to show up for President-elect Trump’s inauguration. Whatever your political persuasion, that would be pretty amazing.

But the source of the information, Right Alerts Polls, is not linked.

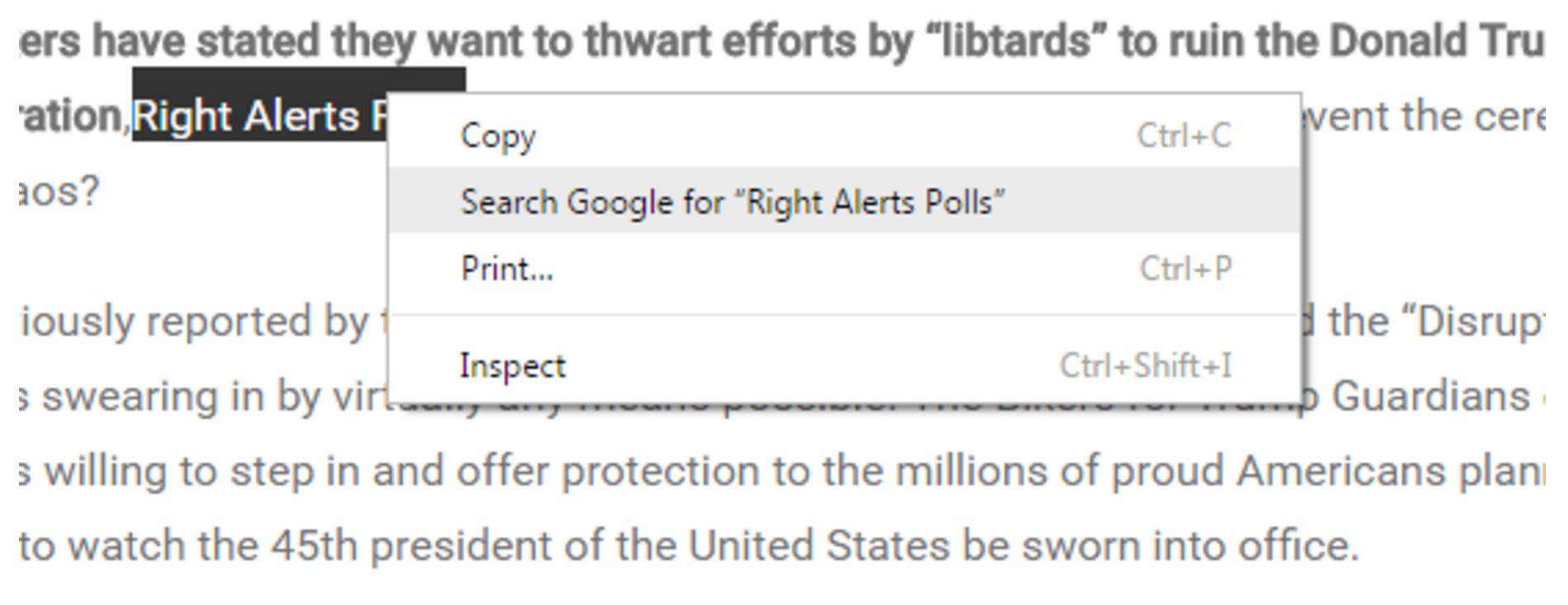

Here is a tip for locating the source. Using the Chrome web browser, select the text “Right Alerts Polls.” Then right-click your mouse (control-click on a Mac), and choose the option to search Google for the highlighted phrase.

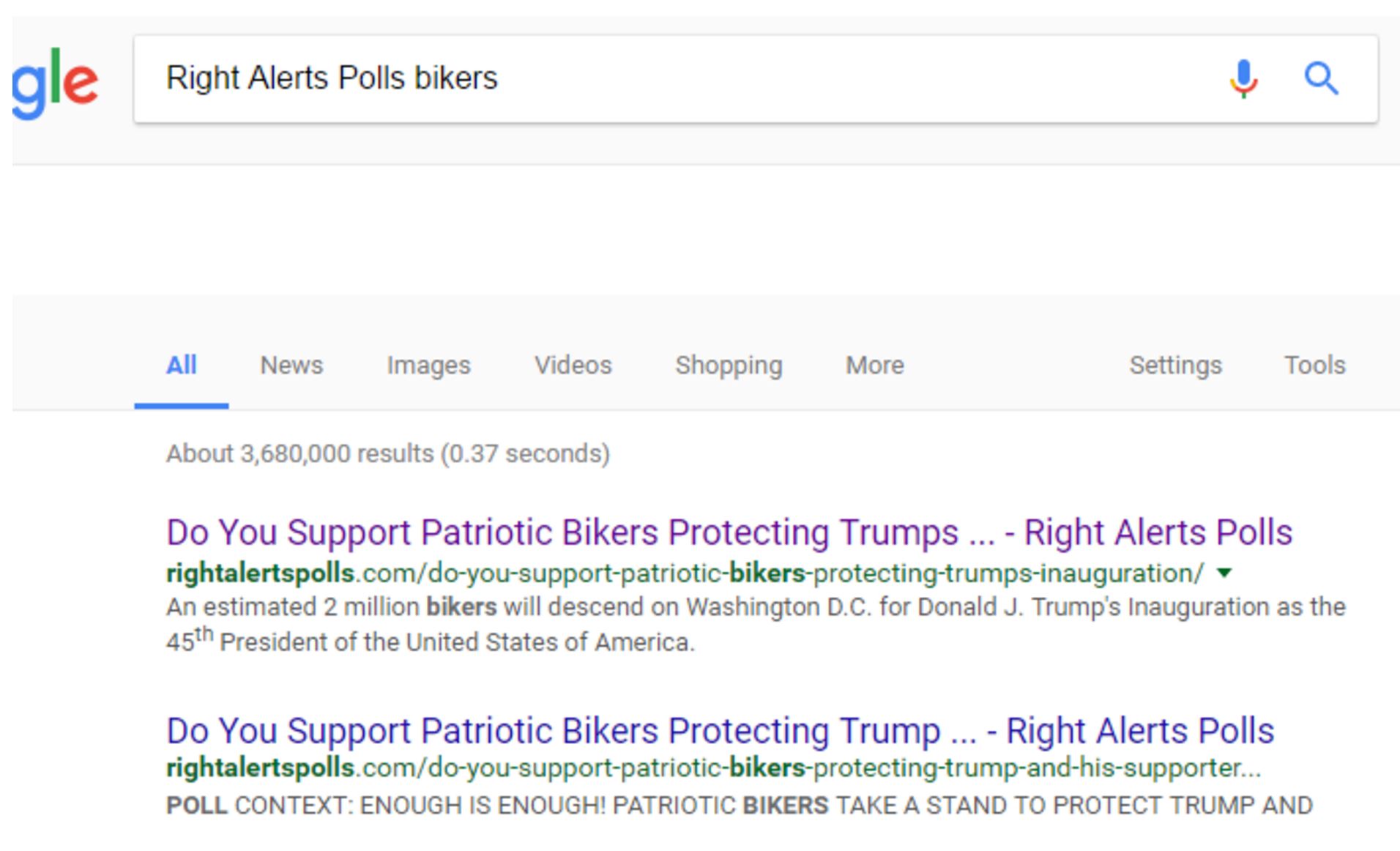

Your computer will execute a search for “Right Alerts Polls.” To find the story, add “bikers” to the end of the search:

Our article appears at the top of the results list. Another option is to go directly to Google and type in the search terms.

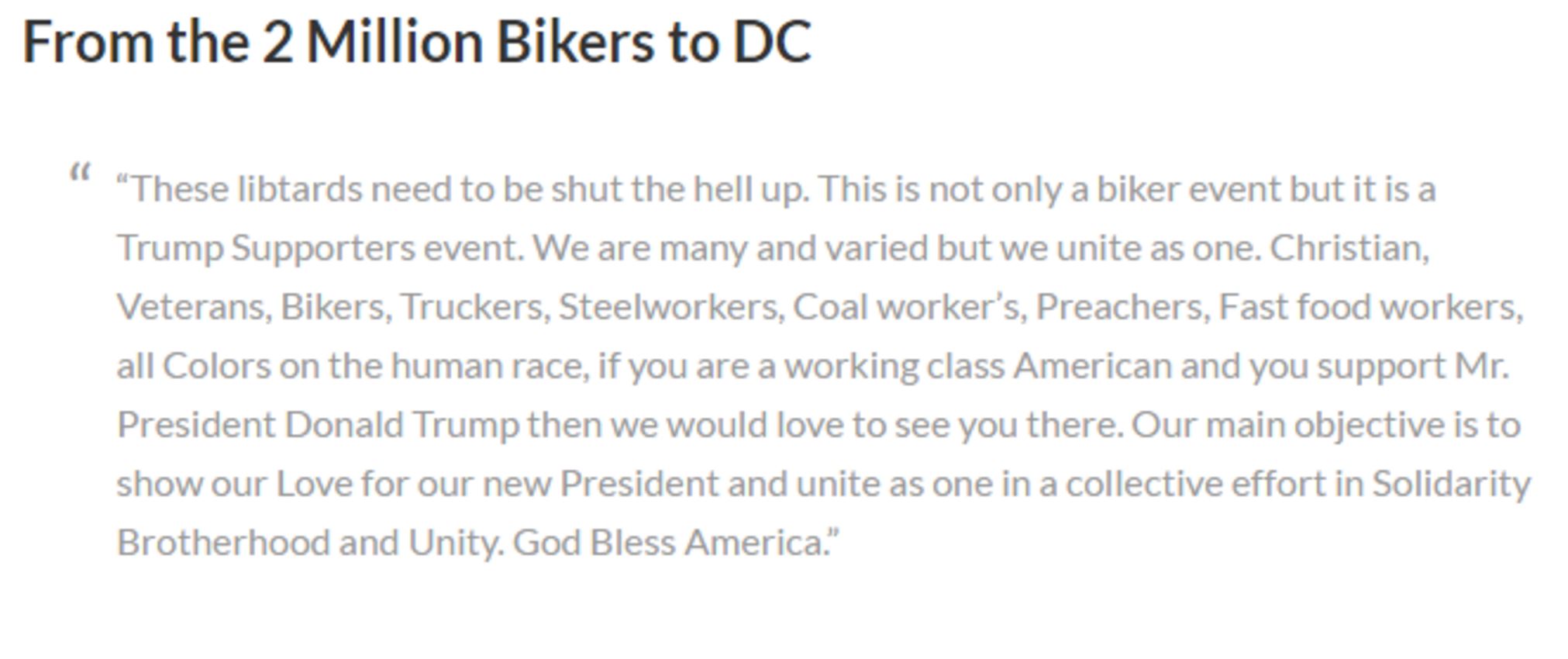

So have we found the source? Not yet. When we click through to the supposed source article, we find that this article does not tell us where the information is coming from; however, it does have an extended quote from one of the “Two Million Bikers” organizers:

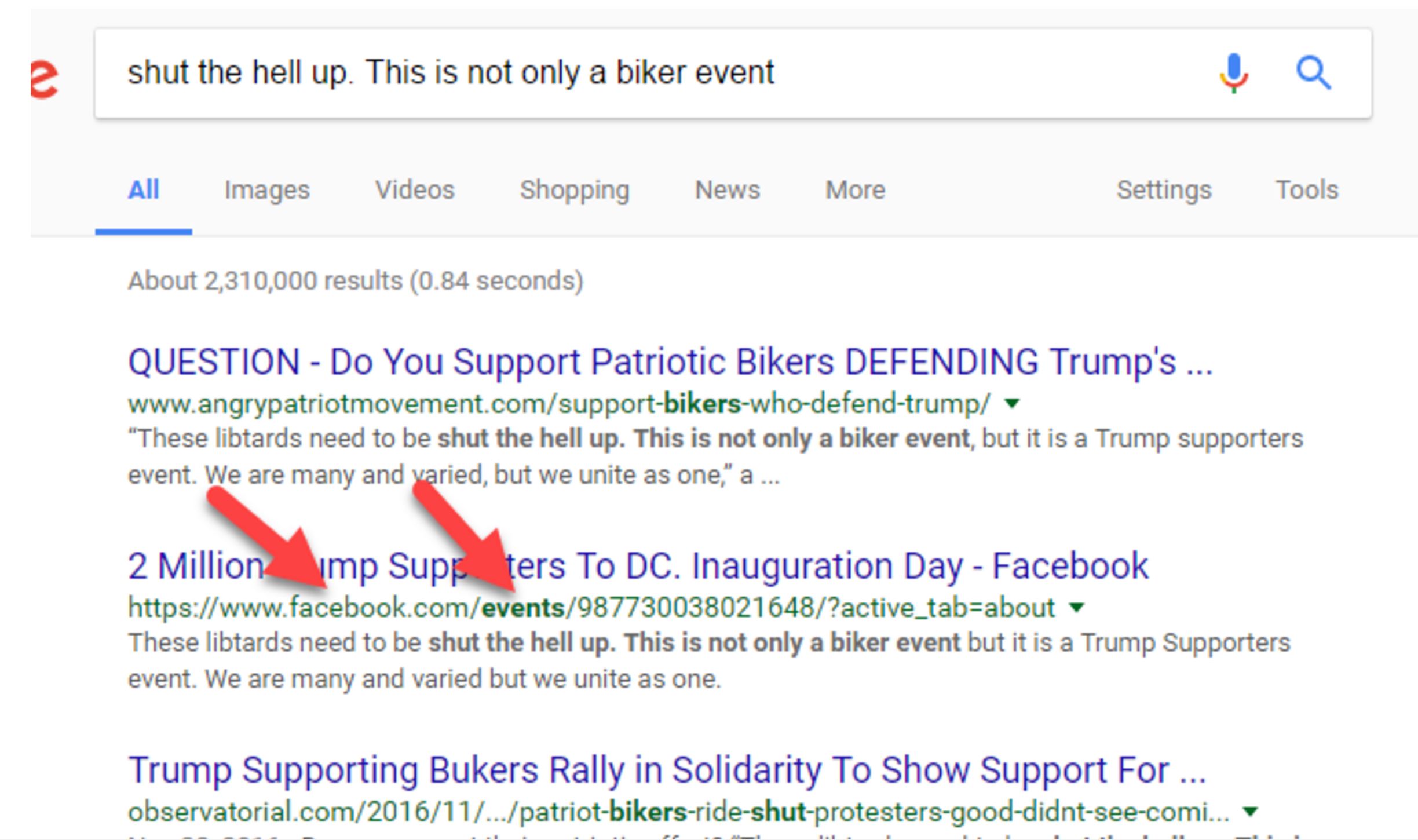

So we just repeat our technique here, and select a bit of text from the quote and right-click/control-click. Our goal is to figure out where this quote came from, and searching on this small but unique piece of it should bring it close to the top of the Google results list.

When we search this snippet of the quote, we see that there are dozens of articles covering this story, using the same quote and sometimes even the same headline. But one of those results is the actual Facebook page for the event, and if we want a sense of how many people are committing, then this is a place to start.

As we begin to develop fact-checking habits, we should remember to not only scan the titles in a result list but also the URLs beneath the titles. These are clues as to which sources are best.

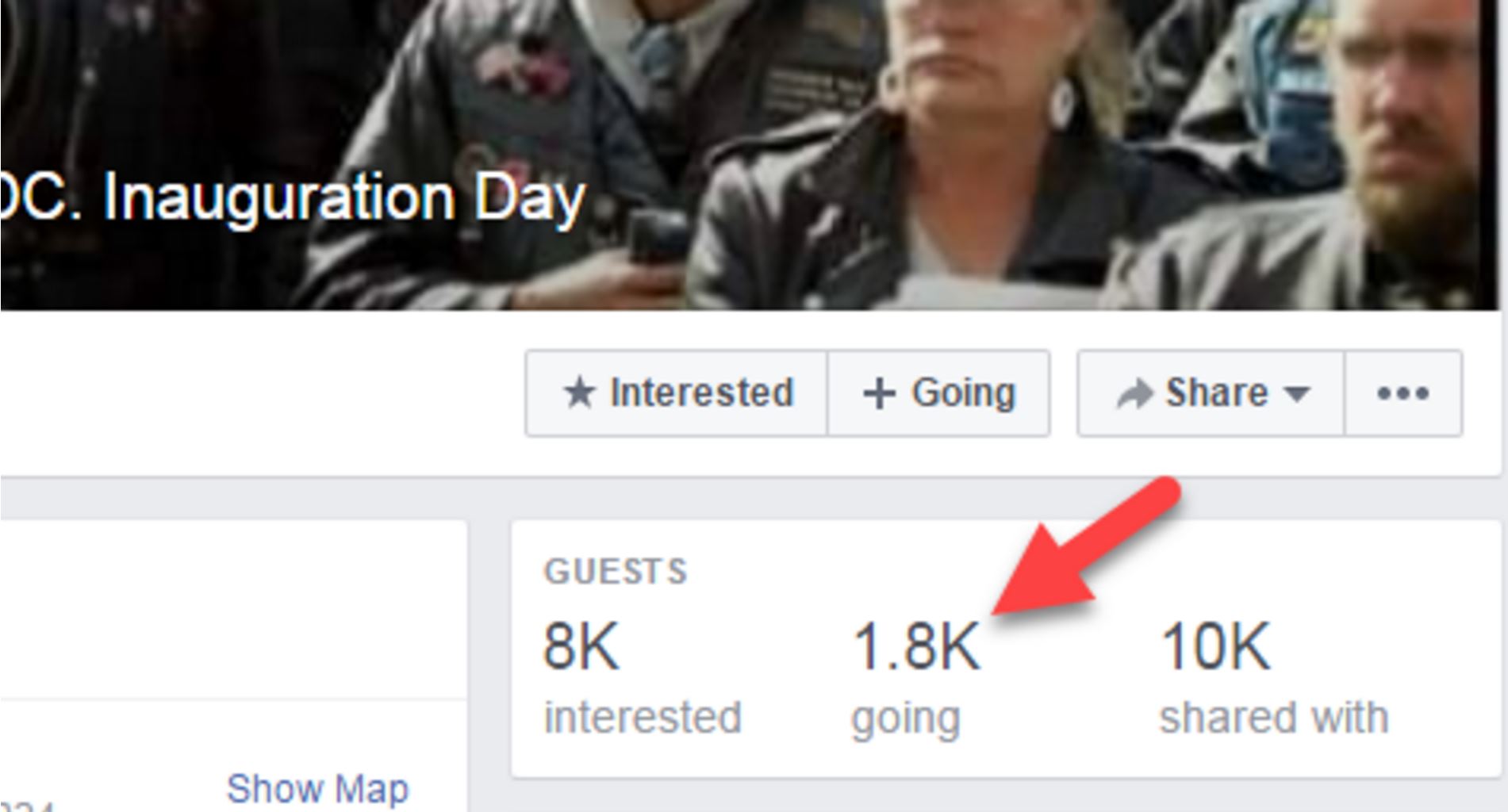

So we go to the “Two Million Biker” Facebook event page, and take a look. How close are they to getting two million bikers to commit to this?

So far, about 1,800 bikers have committed to going to the inauguration. That is quite positive – organizing is hard, and people have lives. Getting people to give up time for a political activity is tough. But it is well short of the “two million bikers” most of these articles were telling us were going to show up.

It appears that the overall numbers are “Mostly False” or “Unlikely” – there are people planning to attend, but the importance of the story was based around the scale of attendance. All indications seem to be that attendance will likely be a tenth of one percent (0.1%) of what the other articles promised. We only learned this by finding the source of the content.