Module 6: Basic Operant Conditioning Principles/Procedures and Respondent Conditioning and Observational Learning

Module Overview

We have now discussed the basics of behavior modification and how the scientific method applies to both psychology and it. In our second part, we began discussing making important, and at times, life-saving changes. Important to this discussion is establishing a precise and objective definition of the target behavior, setting clear distal and proximal goals, changing because you genuinely want to, and then gathering data about the problem/desired behavior. This all leads to a functional assessment in which we can more clearly see the causes of our behavior or non-behavior and what consequences maintain it.

With all this in mind, we now are at the point that we can do something about our issue, whether a deficit or excess. But what do we do? What does our plan include? Modules 7-9 will focus on operant conditioning strategies that can be used to deal with the antecedent, behavior, and/or consequence. Most likely you will use a combination of all three and we will discuss about 30 such strategies across these three modules. Before we get there, we will lay down some basic operant condition principles that you will use throughout the duration of this course and to be candid, life. I do not see this as an exaggeration since you will likely have kids and need to implement some type of reinforcement or punishment. You are almost guaranteed to work, and I bet you will want a paycheck. If so, you will be reinforced for your hard work at a fixed amount of time. And you may find that you or someone you love is making a behavior you will want to get rid of completely, or my favorite word, extinguish. That sounds bad but it really is not. More on this in a bit. We will also discuss the non-operant procedures of respondent conditioning and observational learning, several of which you will see presented in the next three modules.

My advice. Take it slow. Ask questions whether you are taking this course in the classroom or online. It is easy to get confused with the strategies. If you ask questions and figure things out now, you will have success later when asked to apply these strategies to the many scenarios you will see in Part VI of the course. Oh yeah. Don’t forget about your self-modification project too.

Module Outline

- 6.1. Operant Conditioning – Overview

- 6.2. Behavioral Contingencies

- 6.3. Reinforcement Schedules

- 6.4. Take a Pause – Exercises

- 6.5. Extinction and Spontaneous Recovery

- 6.6. Respondent Conditioning

- 6.7. Observational Learning

Module Learning Outcomes

- Clarify how operant conditioning tackles the task of learning.

- List and describe behavioral contingencies. Clarify factors on their effectiveness.

- Outline the four reinforcement schedules.

- Solve problems using behavioral contingencies and schedules of reinforcement.

- Clarify the concepts of extinction and spontaneous recovery.

- Discuss the utility of respondent conditioning in changing unwanted behavior.

- Discuss the utility of observational learning in changing unwanted behavior.

6.1. Operant Conditioning – Overview

Section Learning Objectives

- Clarify what happens when we make a behavior (the framework).

- Define operant conditioning.

- Remember whose groundbreaking work operant conditioning is based on.

Before jumping into a lot of terminology, it is important to understand what operant conditioning is or attempts to do. But before we get there, let’s take a step back. So what happens when we make a behavior? Consider this framework that will look familiar to you:

Recognize it? Two words are different but it should remind you of Antecedent, Behavior, and Consequence. It looks the same because it is the same. Stimulus is another word for antecedent and is whatever comes before the behavior, usually from the environment, but we know that the source of our behavior could be internal too. Response is a behavior. And of course, consequence is the same word. The definitions for these terms are the same as the ones you were given in Module 1 for the ABCs of behavior. Presenting this framework is important, because operant conditioning as a learning model focuses on the person making some response for which there is a consequence. As we learned from Thorndike’s work, if the consequence is favorable or satisfying, we will be more likely to make the response again (when the stimulus occurs). If not favorable or unsatisfying, we will be less likely. In Section 6.7, we will talk about respondent or classical conditioning which developed thanks to Pavlov’s efforts. This type of learning focuses on stimulus and response.

Before moving on let’s state a formal definition for operant conditioning:

Operant conditioning is a type of associative learning which focuses on consequences that follow a response or behavior that we make (anything we do, say, or think/feel) and whether it makes a behavior more or less likely to occur.

6.2. Behavioral Contingencies

Section Learning Objectives

- Contrast reinforcement and punishment.

- Clarify what positive and negative mean.

- Outline the four contingencies of behavior.

- Distinguish primary and secondary reinforcers.

- List and describe the five factors on the effectiveness of reinforcers.

6.2.1. Contingencies

As we have seen, the basis of operant conditioning is that you make a response for which there is a consequence. Based on the consequence you are more or less likely to make the response again. This section introduces the term contingency. A contingency is when one thing occurs due to another. Think of it as an If-Then statement. If I do X, then Y will happen. For operant conditioning this means that if I make a behavior, then a specific consequence will follow. The events (response and consequence) are linked in time.

What form do these consequences take? There are two main ways they can present themselves.

-

- Reinforcement – Due to the consequences, a behavior/response is more likely to occur in the future. It is strengthened.

- Punishment – Due to the consequence, a behavior/response is less likely to occur in the future. It is weakened.

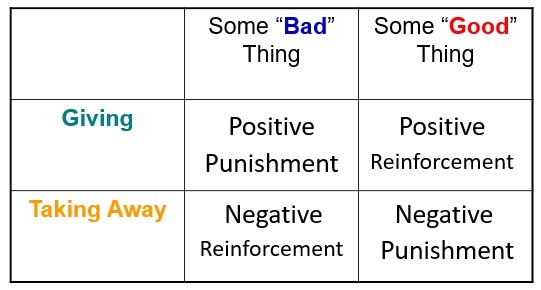

Reinforcement and punishment can occur as two types – positive and negative. These words have no affective connotation to them meaning they do not imply good or bad. Positive means that you are giving something – good or bad. Negative means that something is being taken away – good or bad. Check out the table below for how these contingencies are arranged.

Figure 6.1. Contingencies in Operant Conditioning

Let’s go through each:

- Positive Punishment (PP) – If something bad or aversive is given or added, then the behavior is less likely to occur in the future. If you talk back to your mother and she slaps your mouth, this is a PP. Your response of talking back led to the consequence of the aversive slap being delivered or given to your face.

- Positive Reinforcement (PR) – If something good is given or added, then the behavior is more likely to occur in the future. If you study hard and earn, or are given, an A on your exam, you will be more likely to study hard in the future.

- Negative Reinforcement (NR) – This is a tough one for students to comprehend because the terms don’t seem to go together and are counterintuitive. But it is really simple, and you experience NR all the time. This is when something bad or aversive is taken away or subtracted due to your actions, making it that you will be more likely to make the same behavior in the future when some stimuli presents itself. For instance, what do you do if you have a headache? You likely answered take Tylenol. If you do this and the headache goes away, you will take Tylenol in the future when you have a headache. NR can either result in current escape behavior or future avoidance behavior. Escape occurs when we are presently experiencing an aversive event and want it to end. We make a behavior and if the aversive event, like the headache, goes away, we will repeat the taking of Tylenol in the future. This future action is an avoidance event. We might start to feel a headache coming on and run to take Tylenol right away. By doing so we have removed the possibility of the aversive event occurring and this behavior demonstrates that learning has occurred.

- Negative Punishment (NP) – This is when something good is taken away or subtracted making a behavior less likely in the future. If you are late to class and your professor deducts 5 points from your final grade (the points are something good and the loss is negative), you will hopefully be on time in all subsequent classes.

6.2.2. Primary vs. Secondary (Conditioned)

The type of reinforcer or punisher we use is important. Some are naturally occurring while some need to be learned. We describe these as primary and secondary reinforcers and punishers. Primary refers to reinforcers and punishers that have their effect without having to be learned. Food, water, temperature, and sex, for instance, are primary reinforcers while extreme cold or hot or a punch on the arm are inherently punishing. A story will illustrate the latter. When I was about 8 years old, I would walk on the street in my neighborhood saying, “I’m Chicken Little and you can’t hurt me.” Most ignored me but some gave me the attention I was seeking, a positive reinforcer. So, I kept doing it and doing it until one day, another kid was tired of hearing about my other identity and punched me in the face. The pain was enough that I never walked up and down the street echoing my identity crisis for all to hear. This was a positive punisher and did not have to be learned. That was definitely not one of my finer moments in life.

Secondary or conditioned reinforcers and punishers are not inherently reinforcing or punishing but must be learned. An example was the attention I received for saying I was Chicken Little. Over time I learned that attention was good. Other examples of secondary reinforcers include praise, a smile, getting money for working or earning good grades, stickers on a board, points, getting to go out dancing, and getting out of an exam if you are doing well in a class. Examples of secondary punishers include a ticket for speeding, losing television or video game privileges, being ridiculed, or a fee for paying your rent or credit card bill late. Really, the sky is the limit with reinforcers in particular.

6.2.3. Factors Affecting the Effectiveness of Reinforcers and Punishers

The four contingencies of behavior can be made to be more or less effective by taking a few key steps. These include:

- It should not be surprising to know that the quicker you deliver a reinforcer or punisher after a response, the more effective it will be. This is called immediacy. Don’t be confused by the word. If you notice, you can see immediately in it. If a person is speeding and you ticket them right away, they will stop speeding. If your daughter does well on her spelling quiz, and you take her out for ice cream after school, she will want to do better.

- The reinforcer or punisher should be unique to the situation. So, if you do well on your report card, and your parents give you $25 each A, and you only get money for school performance, the secondary reinforcer of money will have an even greater effect. This ties back to our discussion of contingency.

- But also, you are more likely to work harder for $25 an A than you are $5 an A. This is called magnitude. Premeditated homicide or murder is another example. If the penalty is life in prison and possibly the death penalty, this will have a greater effect on deterring the heinous crime than just giving 10 years in prison with the chance of parole.

- At times, events make a reinforcer or punisher more or less reinforcing or punishing. We call these motivating operations and they can take the form of an establishing or an abolishing operation. If we go to the store when hungry or in a state of deprivation, food becomes even more reinforcing and we are more likely to pick up junk food. This is an establishing operation and is when an event makes a reinforcer or punisher more potent and so more likely to occur. What if you went to the grocery store full or in a state of satiation? In this case, junk food would not sound appealing and you would not buy it and throw your diet off. This is an abolishing operation and is when an event makes a reinforcer or punisher less potent and so less likely to occur. An example of a punisher is as follows: If a kid loves playing video games and you offer additional time on Call of Duty for completing chores both in a timely fashion and correctly, this will be an establishing operation and make Call of Duty even more reinforcing. But what if you offer a child video game time for doing those chores and he or she does not like playing them? This is now an abolishing operation and the video games are not likely to induce the behavior you want.

- The example of the video games demonstrates establishing and abolishing operations, but it also shows one very important fact – all people are different. Reinforcers will motivate behavior. That is a universal occurrence and unquestionable. But the same reinforcers will not reinforce all people. This shows diversity and individual differences. Before implementing any type of behavior modification plan, whether on yourself or another person, you must make sure you have the right reinforcers and punishers in place.

Alright. Now that we have established what contingencies are, let’s move to a discussion of when we reinforce.

6.3. Reinforcement Schedules

Section Learning Objectives

- Contrast continuous and partial/intermittent reinforcement.

- List the four main reinforcement schedules and exemplify each.

In operant conditioning, the rule for determining when and how often we will reinforce a desired behavior is called the reinforcement schedule. Reinforcement can either occur continuously meaning every time the desired behavior is made the person or animal will receive some reinforcer, or intermittently/partially meaning reinforcement does not occur with every behavior. Our focus will be on partial/intermittent reinforcement.

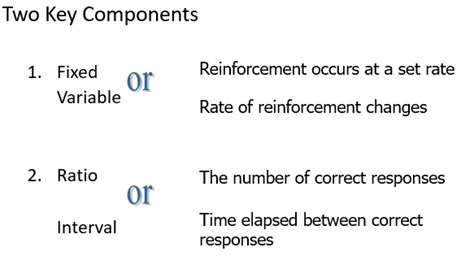

Figure 6.2. Key Components of Reinforcement Schedules

Figure 6.2. shows that that are two main components that make up a reinforcement schedule – when you will reinforce and what is being reinforced. In the case of when, it will be either fixed or at a set rate, or variable and at a rate that changes. In terms of what is being reinforced, we will either reinforce responses or time. These two components pair up as follows:

- Fixed Ratio schedule (FR) – With this schedule, we reinforce some set number of responses. For instance, every twenty problems (fixed) a student gets correct (ratio), the teacher gives him an extra credit point. A specific behavior is being reinforced – getting problems correct. Note that if we reinforce each occurrence of the behavior, the definition of continuous reinforcement, we could also describe this as a FR1 schedule. The number indicates how many responses have to be made and, in this case, it is one.

- Variable Ratio schedule (VR) – We might decide to reinforce some varying number of responses such as if the teacher gives him an extra credit point after finishing between 40 and 50 problems correctly. This is useful after the student is obviously learning the material and does not need regular reinforcement. Also, since the schedule changes, the student will keep responding in the absence of reinforcement.

- Fixed Interval schedule (FI) – With a FI schedule, you will reinforce after some set amount of time. Let’s say a company wanted to hire someone to sell their products. To attract someone, they could offer to pay them $15 an hour 40 hours a week and give this money every two weeks. Crazy idea but it could work. J Saying the person will be paid every indicates fixed, and two weeks is time or interval. So, FI.

- Variable Interval schedule (VI) – Finally, you could reinforce someone at some changing amount of time. Maybe they receive payment on Friday one week, then three weeks later on Monday, then two days later on Wednesday, then eight days later on Thursday. Etc. This could work, right? Not for a job but maybe we could say we are reinforced on a VI schedule if we are.

6.4. Take a Pause – Exercises

Section Learning Objectives

- Practice using contingencies of behavior and reinforcement schedules.

Now that we have discussed the main elements of operant conditioning, let’s make sure you understand how to identify contingencies and schedules of reinforcement.

6.4.1. A Way to Easily Identify Contingencies

Use the following three steps:

- Identify if the contingency is positive or negative. If positive, you should see words indicating something was given, earned, or received. If negative, you should see words indicating something was taken away or removed.

- Identify if a behavior is being reinforced or punished. If reinforced, you will see a clear indication that the behavior increases in the future. If punished, there will be an indication that the behavior decreases in the future.

- The last step is easy. Just put it all together. Indicate first if it is P or N, and then indicate if there is R or P. So you will have either PR, PP, NR, or NP. Check above for what these acronyms mean if you are confused.

Example:

You study hard for your calculus exam and earn an A. Your parents send you $100. In the future, you study harder hoping to receive another gift for an exemplary grade.

- P or N – “Your parents send you $100” but also “earn an A” – You are given an A and money so you have two reinforcers that are given which is P

- R or P – “In the future you study harder….” – behavior increases so R

- Together – PR

To make your life easier, feel free to underline where you see P or N and R or P. You cannot go wrong if you do.

Exercise 6.1. Contingencies of Behavior Practice

Directions: For each of the following examples identify the type of consequence. Remember, in each case a consequence is something that follows a behavior. Consequences may increase or decrease the likelihood (in the future) of the behavior that they follow. For example:

- PR (positive reinforcement): Something good is presented, which encourages the behavior in the future.

- NR (negative reinforcement): Something bad is removed or avoided, which encourages the behavior.

- PP (positive punishment): Something bad is presented, which discourages the behavior in the future.

- NP (negative punishment): Something good is removed, which discourages the behavior in the future.

Write or type the two-letter abbreviation in the box to the left of the question.

| 1. Police stop drivers and give them a prize if their seat belts are buckled; seat belt use increases in town. | |

| 2. A basketball player who commits a flagrant foul is removed from the game; his fouls decrease in later games. | |

| 3. A soccer player rolls her eyes at a teammate who delivered a bad pass; the teammate makes fewer errors after that. | |

| 4. To help decrease muscle aches when you are sore you take a hot bath. Since your aches went away, in the future you take a hot bath when you are sore. | |

| 5. After a good workout in physical therapy, hospital patients are given ice cream sundaes. They work harder in later sessions. | |

| 6. Homeowners who recycle get to deduct 5 percent from their utility bill. Recycling increases after this program begins. | |

| 7. After completing an alcohol education program, the suspension of your driver’s license is lifted. More DWI drivers now complete the program. | |

| 8. After Jodi flirted with another guy at a party her boyfriend stopped talking to her. Jodi didn’t flirt at the next party. | |

| 9. The employee of the month is rewarded with a reserved parking space. Employees now work harder. | |

| 10. A dog is sent to his doghouse after soiling the living room carpet. The dog has fewer accidents after that. | |

| 11. A professor allows students with A averages in the class to skip the final exam. Students work harder for A’s. | |

| 12. You clean up your stuff more regularly now to avoid your roommate’s (or mother’s) nagging. | |

| 13. You wax your skis making them go faster. In the future, you wax them before skiing. | |

| 14. You do not study for your Psycholgy 101 exam and your earn an F. Your parents scold you over the phone. | |

| 15. To deal with hunger pangs, you eat food and feel better. In the future you seek out food when you feel the pangs. | |

| 16. You do not study for your Psychology 101 exam and your sorority or fraternity expels you from the house. | |

| 17. You intentionally do not reply to an e-mail from your boss and are given a reprimand. In the future, you do not ignore her emails. | |

| 18. You are given a kiss by your girlfriend after you surprise her with a rose. In the future, you are more likely to shower her with gifts. | |

| 19. You never surprise your boyfriend with anything nice to show him how much you appreciate him. Therefore, he refrains from talking to or kissing you. | |

| 20. Your computer shuts down after you do not plug it in and allow it to recharge. In the future, you plug it in when the battery indicator flashes red to avoid it shutting down and you losing work | |

| 21. A cat keeps confusing the sofa for the litter box and so its owner removes its feeding dish to discourage this smelly behavior. | |

| 22. The sun is bright on the horizon. You put on your sunglasses and the discomfort is reduced. In the future, you put on sunglasses in the same situation. | |

| 23. You earn an A on your exam. Your professor praises you. In the future you study more. | |

| 24. You and your brother are fighting over the PS3. Your parents take it away for one week and fighting decreases in the future. | |

| 25. The annoying child jumps up and down, hand raised, yelling “Me, me, me!” until the teacher calls on her. The child jumps and yells even more in the future. When you answer, consider that there could be two reinforcement schedules going on. What are they? (i.e. In other words, there are two schedules at work) |

Please see the answer key at the back of the book under Exercises after you have tried the exercise on your own.

6.4.2. A Way to Easily Identify Reinforcement Schedules

Use the following three steps:

- When does reinforcement occur? Is it at a set or varying rate? If fixed (F), you will see words such as set, every, and each. If variable (V), you will see words like sometimes or varies.

- Next, determine what is reinforced – some number of responses or time. If a response (R), you will see a clear indication of a behavior that is made. If interval (I), some indication of a specific or period of time will be given.

- Put them together. First identify the rate. Write an F or V. Next identify the what and write a R or I. This will give you one of the pairings mentioned above – FI, FR, VI, or VR.

Example:

You girlfriend or boyfriend display affection about every three times you give him/her a compliment or flirt.

- F or V – “about every three times” which is V.

- R or I – “give him/her a compliment or flirt” which is a response.

- Together – VR

To make your life easier, feel free to underline where you see F or V and R or I. You cannot go wrong if you do, as with the contingencies exercise.

Exercise 6.2. Reinforcement Schedules Practice

Write or type the two-letter abbreviation in the box to the left of the question.

| 1. You get paid on the 10th and 25th of every month. | |

| 2. A worker is paid $2 for every 150 envelopes stuffed. | |

| 3. Slot machines at casinos pay off after a variable number of times the handle is pulled. | |

| 4. Students are released from class when the bell rings. | |

| 5. A fisherman casts and reels back his line several times before he catches a fish. | |

| 6. You get a nickel for every soda can you take to your local recycling center. | |

| 7. Every time you make a purchase at your local sub shop you earn points for the purchase. With every 75 points earned, you receive a free foot-long sub. | |

| 8. Sometimes the mail is delivered at 1:00, sometimes closer to 2:00. | |

| 9. A used car salesperson is paid commission by the dealership for each sale she makes. | |

| 10. Consider the same salesperson in item #9. Does she get a sale for every car she attempts to sell? What schedule does this represent? | |

| 11. You receive a small increase in your hourly wage once a year. | |

| 12. A teacher programs a buzzer to go off at various times during the period. If students are on task they receive a reward. | |

| 13. Matt gets a hit about once every three times he swings the bat. | |

| 14. Every time Matt gets a hit, however, the fans cheer, making him feel good and want to get more hits. | |

| 15. A child receives a star on the board when he is good and makes positive contributions to the class discussions, as determined by his teacher and after some random amount of contributions each day. Every three stars earn him a prize from the prize box. Is there more than one schedule present here? If so, what are they? |

Please see the answer key at the back of the book under Exercises after you have tried the exercise on your own.

6.5. Extinction and Spontaneous Recovery

Section Learning Objectives

- Define extinction.

- Clarify which type of reinforcement extinguishes quicker.

- Define extinction burst.

- Define spontaneous recovery.

In this section, we will discuss two properties of operant conditioning – extinction and spontaneous recovery. Later in the course, we will discuss two others – discrimination and generalization. Keep them on the backburner for now.

6.5.1. Extinction

First, extinction is when something that we do, say, think/feel has not been reinforced for some time. As you might expect, the behavior will begin to weaken and eventually stop when this occurs. Does extinction just occur as soon as the anticipated reinforcer is not there? The answer is yes and no, depending on whether we are talking about continuous or partial reinforcement. With which type of reinforcement would you expect a person to stop responding to immediately if reinforcement is not there?

Do you suppose continuous? Or partial?

The answer is continuous. If a person is used to receiving reinforcement every time the correct behavior is made and then suddenly no reinforcer is delivered, he or she will cease the response immediately. Obviously then, with partial reinforcement, a response continues being made for a while. Why is this? The person may think the schedule has simply changed. ‘Maybe I am not paid weekly now. Maybe it changed to biweekly and I missed the email.’ Due to this we say that intermittent or partial reinforcement shows resistance to extinction, meaning the behavior does weaken, but gradually.

As you might expect, if reinforcement “mistakenly” occurs after extinction has started, the behavior will re-emerge. Consider your parents for a minute. To stop some undesirable behavior you made in the past surely they took away some privilege. I bet the bad behavior ended too. But did you ever go to your grandparent’s house and grandma or grandpa, or worse, BOTH….. took pity on you and let you play your video games for an hour or two (or something equivalent)? I know my grandmother used to. What happened to that bad behavior that had disappeared? Did it start again and your parents could not figure out why? Don’t worry. Someday your parents will get you back and do the same thing with your kid(s). J

When extinction first occurs, the person or animal is not sure what is going on and begins to make the response more often (frequency), longer (duration), and more intensely. This is called an extinction burst. We might even see novel behaviors such as aggression. I mean. Who likes having their privileges taken away? That will likely create frustration which can lead to aggression.

One final point about extinction is important. You must know what the reinforcer is and be able to eliminate it. Say your child bullies other kids at school. Since you cannot be there to stop the behavior, and most likely the teacher cannot be either if done on the playground at recess, the behavior will continue. Your child will continue bullying because it makes him or her feel better about themselves (a PR).

With all this in mind, you must have wondered if extinction is the same as punishment. With both, isn’t it correct that you are stopping an undesirable behavior? Yes, but that is the only similarity they share. Punishment reduces unwanted behavior by either giving something bad or taking away something good. Extinction is simply when you take away the reinforcer for the behavior. This could be seen as taking away something good, but the good in punishment is not usually what is reinforcing the bad behavior. If a child misbehaves (the bad behavior) for attention (the PR), then with extinction you would not give the PR (meaning nothing happens) while with punishment, you might slap his or her behind (a PP) or taking away tv time (an NP).

6.5.2. Spontaneous Recovery

You might have wondered if the person or animal will try to make the response again in the future even though it stopped being reinforced in the past. The answer is yes, and one of two outcomes is possible. First, the response is made and nothing happens. In this case extinction continues. Second, the response is made and a reinforcer is delivered. The response re-emerges. Consider a rat that has been trained to push a lever to receive a food pellet. If we stop delivering the food pellets, in time, the rat will stop pushing the lever. The rat will push the lever again sometime in the future and if food is delivered, the behavior spontaneously recovers.

6.6. Respondent Conditioning

Section Learning Objectives

- Clarify the importance of Pavlov’s work.

- Describe how respondent behaviors work.

- Describe Pavlov’s classic experiment, defining any key terms.

- Explain how fears are both learned and unlearned in respondent conditioning.

- Name the four principles discussed in operant conditioning and explain how they relate to respondent conditioning too.

6.6.1. Pavlov and His Dogs

You have likely heard about Pavlov and his dogs but what you may not know is that this was a discovery made accidentally. Ivan Petrovich Pavlov (1906, 1927, 1928), a Russian physiologist, was interested in studying digestive processes in dogs in response to being fed meat powder. What he discovered was the dogs would salivate even before the meat powder was presented. They would salivate at the sound of a bell, footsteps in the hall, a tuning fork, or the presence of a lab assistant. Pavlov realized there were some stimuli that automatically elicited responses (such as salivating to meat powder) and those that had to be paired with these automatic associations for the animal or person to respond to it (such as salivating to a bell). Armed with this stunning revelation, Pavlov spent the rest of his career investigating the learning phenomenon.

The important thing to understand is that not all behaviors occur due to reinforcement and punishment as operant conditioning says. In the case of respondent condition, antecedent stimuli exert complete and automatic control over some behaviors. We see this in the case of reflexes. When a doctor strikes your knee with that little hammer it extends out automatically. You do not have to do anything but watch. Babies will root for a food source if the mother’s breast is placed near their mouth. If a nipple is placed in their mouth, they will also automatically suck, as per the sucking reflex. Humans have several of these reflexes though not as many as other animals due to our more complicated nervous system.

6.6.2. Respondent conditioning

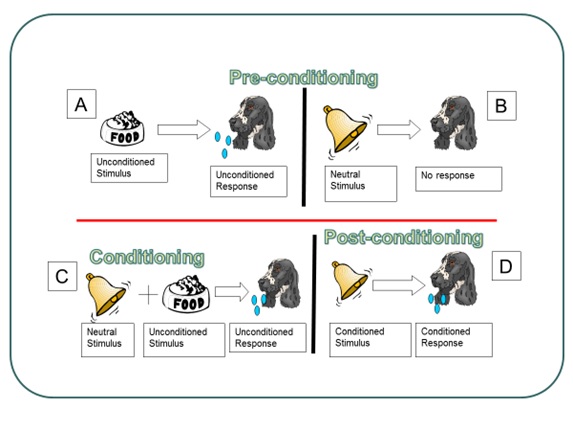

Respondent conditioning occurs when we link a previously neutral stimulus with a stimulus that is unlearned or inborn, called an unconditioned stimulus. In respondent conditioning, learning occurs in three phases: preconditioning, conditioning, and postconditioning. See Figure 6.3 for an overview of Pavlov’s classic experiment.

Preconditioning. Notice that preconditioning has both an A and a B panel. Really, all this stage of learning signifies is that some learning is already present. There is no need to learn it again as in the case of primary reinforcers and punishers in operant conditioning. In Panel A, food makes a dog salivate. This does not need to be learned and is the relationship of an unconditioned stimulus (UCS) yielding an unconditioned response (UCR). Unconditioned means unlearned. In Panel B, we see that a neutral stimulus (NS) yields nothing. Dogs do not enter the world knowing to respond to the ringing of a bell (which it hears).

Conditioning. Conditioning is when learning occurs. Through a pairing of neutral stimulus and unconditioned stimulus (bell and food, respectively) the dog will learn that the bell ringing (NS) signals food coming (UCS) and salivate (UCR). The pairing must occur more than once so that needless pairings are not learned such as someone farting right before your food comes out and now you salivate whenever someone farts (…at least for a while. Eventually the fact that no food comes will extinguish this reaction but still, it will be weird for a bit).

Postconditioning. Postconditioning, or after learning has occurred, establishes a new and not naturally occurring relationship of a conditioned stimulus (CS; previously the NS) and conditioned response (CR; the same response). So the dog now reliably salivates at the sound of the bell because he expects that food will follow, and it does.

Comprehension check. A lot of terms were thrown at you in the preceding three paragraphs and so a quick check will make sure you understand. First, we talk about stimuli and responses being unconditioned or conditioned. The term conditioned means learned and if it is unconditioned then it is unlearned. Next, a stimulus (or stimuli) is an event/object in your environment that you detect via your five sensory systems – vision, hearing, taste, touch, and smell. A response is a behavior that you make due to one of these stimuli. Finally, pre means before and post means after, so preconditioning comes before learning occurs, conditioning is when learning is occurring, and postconditioning is what happens after learning has occurred. Be sure to keep these terms straight and this explanation is an easy way to do so.

Figure 6.3. Pavlov’s Classic Experiment

6.6.3. Learning (and unlearning) Phobias

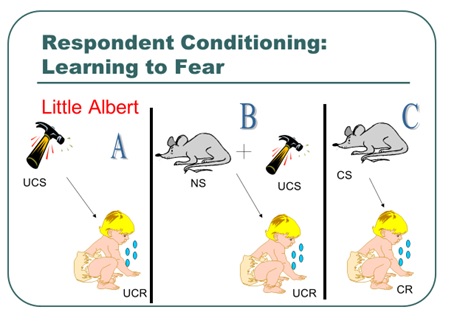

One of the most famous studies in psychology was conducted by Watson and Rayner (1920). Essentially, they wanted to explore “the possibility of conditioning various types of emotional response(s).” The researchers ran a 9-month-old child, known as Little Albert, through a series of trials in which he was exposed to a white rat to which no response was made outside of curiosity (NS–NR not shown).

In Panel A of Figure 6.4, we have the naturally occurring response to the stimulus of a loud sound. On later trials, the rat was presented (NS) and followed closely by a loud sound (UCS; Panel B). After several conditioning trials, the child responded with fear to the mere presence of the white rat (Panel C).

Figure 6.4. Learning to Fear

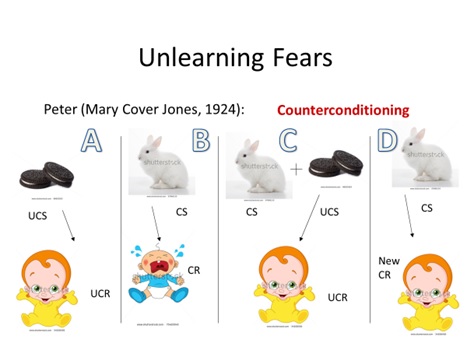

As fears can be learned, so too they can be unlearned. Considered the follow-up to Watson and Rayner (1920), Jones (1924; Figure 6.5) wanted to see if a child who learned to be afraid of white rabbits (Panel B) could be conditioned to become unafraid of them. Simply, she placed the child in one end of a room and then brought in the rabbit. The rabbit was far enough away so as to not cause distress. Then, Jones gave the child some pleasant food (i.e., something sweet such as cookies [Panel C]; remember the response to the food is unlearned, i.e., Panel A). The procedure in Panel C continued with the rabbit being brought in a bit closer each time to eventually the child did not respond with distress to the rabbit (Panel D).

Figure 6.5. Unlearning Fears

This process is called counterconditioning, or the reversal of previous learning.

Another respondent conditioning way to unlearn a fear is what is called flooding or exposing the person to the maximum level of stimulus and as nothing aversive occurs, the link between CS and UCS producing the CR of fear should break, leaving the person unafraid. That is the idea at least and if you were afraid of clowns, you would be thrown into a room full of clowns. Hmm….

6.6.4. Other Key Concepts

In operant conditioning we talked about generalization, discrimination, extinction, and spontaneous recovery. These terms apply equally as well to respondent conditioning as follows:

- Respondent Generalization – When a number of similar CSs or a broad range of CSs elicit the same CR. An example is the sound of a whistle eliciting salivation the same as the sound of a bell, both detected via audition.

- Respondent Discrimination – When the CR is elicited by a single CS or a narrow range of CSs. Teaching the dog to not respond to the whistle but only to the bell, and just that type of bell. Other bells would not be followed by food, eventually leading to….

- Respondent Extinction – When the CS is no longer paired with the UCS. The sound of a school bell ringing (new CS that was generalized) is not followed by food (UCS), and so eventually the dog stops salivating (the CR).

- Spontaneous recovery – When the CS elicits the CR after extinction has occurred. Eventually, the school bell will ring making the dog salivate. If no food comes, the behavior will not continue on. If food comes, the salivation response will be re-established.

So again, all four terms from operant conditioning apply in respondent conditioning too.

6.7. Observational Learning

Section Learning Objectives

- Differentiate observational and enactive learning.

- Describe Bandura’s classic experiment.

- Clarify how observational learning can be used in behavior modification.

6.7.1. Learning by Watching Others

There are times when we learn by simply watching others. This is called observational learning and is contrasted with enactive learning, which is learning by doing. There is no firsthand experience by the learner in observational learning unlike enactive. As you can learn desirable behaviors such as watching how your father bags groceries at the grocery store (I did this and still bag the same way today) you can learn undesirable ones too. If your parents resort to alcohol consumption to deal with the stressors life presents, then you too might do the same. What is critical is what happens to the model in all of these cases. If my father seems genuinely happy and pleased with himself after bagging groceries his way, then I will be more likely to adopt this behavior. If my mother or father consumes alcohol to feel better when things are tough, and it works, then I might do the same. On the other hand, if we see a sibling constantly getting in trouble with the law then we may not model this behavior due to the negative consequences.

6.7.2. Bandura’s Classic Experiment

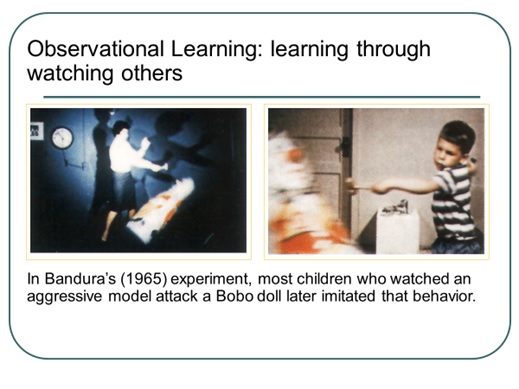

Albert Bandura conducted the pivotal research on observational learning and you likely already know all about it. Check out Figure 6.6 to see if you do. In Bandura’s experiment, children were first brought into a room to watch a video of an adult playing nicely or aggressively with a Bobo doll. This was a model. Next, the children are placed in a room with a lot of toys in it. In the room is a highly prized toy but they are told they cannot play with it. All other toys are fine and a Bobo doll is in the room. Children who watched the aggressive model behaved aggressively with the Bobo doll while those who saw the nice model, played nice. Both groups were frustrated when deprived of the coveted toy.

Figure 6.6. Bandura’s Classic Experiment

6.7.3. Observational Learning and Behavior Modification

Bandura said if all behaviors are learned by observing others and we model our behaviors on theirs, then undesirable behaviors can be altered or relearned in the same way. Modeling techniques are used to change behavior by having subjects observe a model in a situation that usually causes them some anxiety. By seeing the model interact nicely with the fear evoking stimulus, their fear should subside. This form of behavior therapy is widely used in clinical, business, and classroom situations. In the classroom, we might use modeling to demonstrate to a student how to do a math problem. In fact, in many college classrooms this is exactly what the instructor does. In the business setting, a model or trainer demonstrates how to use a computer program or run a register for a new employee. At the gym, a trainer will demonstrate how to use a weight machine.

6.7.4. Final Word on Modeling

To end our discussion on modeling I thought it would be important to point out that we do not model everything we see. Why? First, we cannot pay attention to everything going on around us. We are more likely to model behaviors by someone who commands our attention. Second, we must remember what a model does in order to imitate it. If a behavior is not memorable, it will not be imitated. Third, we must try to convert what we see into action. If we are not motivated to perform an observed behavior, we probably will not show what we have learned.

Module Recap

As I noted, we are now to the business of identifying strategies we can use to modify our behavior. To help you understand what you are about to learn, Module 6 presented the four contingencies of behavior, the four schedules of reinforcement, and then explained the concepts of extinction and spontaneous recovery. We also practiced with these concepts to ensure you understand them. Finally, we discussed respondent conditioning and observational learning procedures, to include flooding and modeling, respectively.

Before moving on, let your instructor know if you are still confused. Once ready, take on the topic of antecedent focused strategies in Module 7.