16

Learning Objectives

By the end of the chapter, you should be able to:

- Describe strategies to minimize and manage debt.

- Explain how to manage monthly income and expenses.

- Define personal finances and financial planning.

- Explain the financial planning life cycle.

- Discuss the advantages of a college education in meeting short-term and long-term financial goals.

- Explain compound interest and the time value of money.

- Discuss the value of getting an early start on your plans for saving.

Show What You Know

The World of Personal Credit

Do you sometimes wonder where your money goes? Do you worry about how you’ll pay off your student loans? Would you like to buy a new car or even a home someday and you’re not sure where you’ll get the money? If these questions seem familiar to you, you could benefit from help in managing your personal finances, which this chapter will seek to provide.

Do you sometimes wonder where your money goes? Do you worry about how you’ll pay off your student loans? Would you like to buy a new car or even a home someday and you’re not sure where you’ll get the money? If these questions seem familiar to you, you could benefit from help in managing your personal finances, which this chapter will seek to provide.

Let’s say that you’re twenty-eight and single. You have a good education and a good job—you’re pulling down $60K working with a local accounting firm. You have $6,000 in a retirement savings account, and you carry three credit cards. You plan to buy a condo in two or three years, and you want to take your dream trip to the world’s hottest surfing spots within five years. Your only big worry is the fact that you’re $70,000 in debt, due to student loans, your car loan, and credit card debt. In fact, even though you’ve been gainfully employed for a total of six years now, you haven’t been able to make a dent in that $70,000. You can afford the necessities of life and then some, but you’ve occasionally wondered if you’re ever going to have enough income to put something toward that debt.[1]

You’re not alone! The average student in Canada will graduate in 2018 having accumulated over $27,000 in student debt. But this is not the only financial problem in Canada. Canadian household debt has reached a record high of over $2.08 trillion as of September 2017, that is $1.68 of debt for every $1 of income.

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development began measuring the financial literacy of its OECD countries using a 5 question survey. This simple 5 question survey tests basic financial literacy knowledge. Take the survey!

Personal financial literacy is more important than ever in Canada. As a country we need to improve our financial literacy. The Bank for International Settlements, an “international watchdog” regarding country economic risk, has warned that Canada’s banking system is at risk due to the rising collective household debt level. In the coming chapter you will learn the basics of personal financial literacy.

Time Is Money

The fact that you have to choose a career at an early stage in your financial life cycle isn’t the only reason that you need to start early, on your financial planning. Let’s assume, for instance, that it’s your eighteenth birthday and that on this day you take possession of $10,000 that your grandparents put in trust for you. You could, of course, spend it; in particular, it would probably cover the cost of flight training for a private pilot’s license—something you’ve always wanted but were convinced that you couldn’t afford right away. Your grandfather, of course, suggests that you put it into some kind of savings account. This way, your $10,000 could take advantage of something called interest. Interest is the charge for the privilege of borrowing money, typically expressed as an annual percentage rate, or is the payment made to you from the investing institution on top of the principal amount you invested of $10,000. If you just wait until you finish college, he says, and if you can find a savings plan that pays 5 percent interest, you’ll have the $10,000 plus about another $2,000 for something else or to invest.

The total amount you’ll have— $12,000—piques your interest. If that $10,000 could turn itself into $12,000 after sitting around for four years, what would it be worth if you actually held on to it until you did retire—say, at age sixty-five? A quick trip to the Internet to find a compound-interest calculator informs you that, forty-seven years later, your $10,000 will have grown to $104,345 (assuming a 5 percent interest rate). That’s not really enough to retire on, but it would be a good start. On the other hand, what if that four years in college had paid off the way you planned, so that once you get a good job you’re able to add, say, another $10,000 to your retirement savings account every year until age sixty-five? At that rate, you’ll have amassed a nice little nest egg of slightly more than $1.6 million.

Compound Interest

In your efforts to appreciate the potential of your $10,000 to multiply itself, you have acquainted yourself with two of the most important concepts in finance. As we’ve already indicated, one is the principle of compound interest, which refers to the effect of earning interest on your interest.

Let’s say, for example, that you take your grandfather’s advice and invest your $10,000 (your principal) in a savings account at an annual interest rate of 5 percent. Over the course of the first year, your investment will earn $500 in interest and grow to $10,500. If you now reinvest the entire $10,500 at the same 5 percent annual rate, you’ll earn another $525 in interest, giving you a total investment at the end of year 2 of $11,025. And so forth. And that’s how you can end up with $81,496.67 at age sixty-five.

Prefer a video to help you decipher and understand compound interest? Watch Khan Academy’s seven minute explanation:

Time Value of Money

You’ve also encountered the principle of the time value of money—the principle whereby a dollar received in the present is worth more than a dollar received in the future. If there’s one thing that we’ve stressed throughout this chapter so far, it’s the fact that most people prefer to consume now rather than in the future. If you borrow money from me, it’s because you can’t otherwise buy something that you want at the present time. If I lend it to you, I must forego my opportunity to purchase something I want at the present time. I will do so only if I can get some compensation for making that sacrifice, and that’s why I’m going to charge you interest. And you’re going to pay the interest because you need the money to buy what you want to buy now. How much interest should we agree on? In theory, it could be just enough to cover the cost of my lost opportunity, but there are, of course, other factors. Inflation, which is the general increase in prices of goods and services and the corresponding decrease in the purchasing power of money, for example, will have eroded the value of my money by the time I get it back from you. In addition, while I would be taking no risk in loaning money to the Canadian government, I am taking a risk in lending it to you. Our agreed-on rate will reflect such factors.[2]

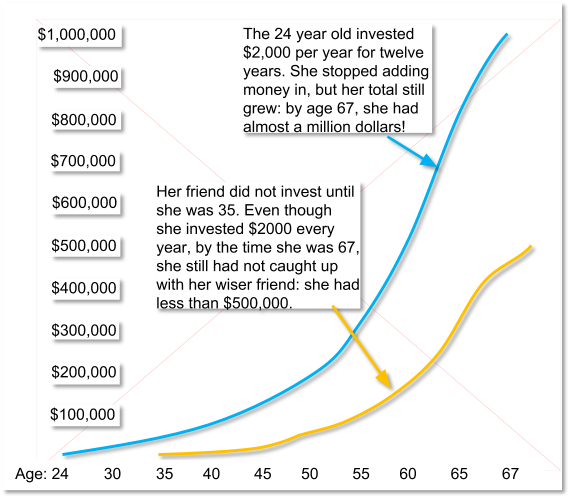

Finally, the time value of money principle also states that a dollar received today starts earning interest sooner than one received tomorrow. Let’s say, for example, that you receive $2,000 in cash gifts when you graduate from college. At age twenty-three, with your college degree in hand, you get a decent job and don’t have an immediate need for that $2,000. So you put it into an account that pays 10 percent compounded and you add another $2,000 ($167 per month) to your account every year for the next eleven years.[3] The blue line in the graph below shows how much your account will earn each year and how much money you’ll have at certain ages between twenty-four and sixty-seven.

As you can see, you’d have nearly $52,000 at age thirty-six and a little more than $196,000 at age fifty; at age sixty-seven, you’d be just a bit short of $1 million. The yellow line in the graph shows what you’d have if you hadn’t started saving $2,000 a year until you were age thirty-six. As you can also see, you’d have a respectable sum at age sixty-seven—but less than half of what you would have accumulated by starting at age twenty-three. More important, even to accumulate that much, you’d have to add $2,000 per year for a total of thirty-two years, not just twelve.

Here’s another way of looking at the same principle. Suppose that you’re twenty years old, don’t have $2,000, and don’t want to attend college full-time. You are, however, a hard worker and a conscientious saver, and one of your financial goals is to accumulate a $1 million retirement nest egg. As a matter of fact, if you can put $33 a month into an account that pays 12 percent interest compounded,[4] you can have your $1 million by age sixty-seven. That is, if you start at age twenty. As you can see from the figure below, if you wait until you’re twenty-one to start saving, you’ll need $37 a month. If you wait until you’re thirty, you’ll have to save $109 a month, and if you procrastinate until you’re forty, the ante goes up to $366 a month.[5] Unfortunately in today’s low interest rate environment, finding 10 to 12% return is not likely. Nevertheless, these figures illustrate the significant benefit of saving early.

How to save a million dollars by age 67 |

|

|---|---|

Make your first payment at age: |

And this is what you’ll have to save each month: |

|

20 |

$33 |

|

21 |

$37 |

|

22 |

$42 |

|

23 |

$47 |

|

24 |

$53 |

|

25 |

$60 |

|

26 |

$67 |

|

27 |

$76 |

|

28 |

$85 |

|

30 |

$109 |

|

35 |

$199 |

|

40 |

$366 |

|

50 |

$1,319 |

|

60 |

$6,253 |

The reason should be fairly obvious: a dollar saved today not only starts earning interest sooner than one saved tomorrow (or ten years from now) but also can ultimately earn a lot more money in the long run. Starting early means in your twenties—early in stage 1 of your financial life cycle. As one well-known financial advisor puts it, “If you’re in your 20s and you haven’t yet learned how to delay gratification, your life is likely to be a constant financial struggle.”[6]

Financial Planning

Before we go any further, we need to nail down a couple of key concepts. First, just what, exactly, do we mean by personal finances? Finance itself concerns the flow of money from one place to another, and your personal finances concern your money and what you plan to do with it as it flows in and out of your possession. Essentially, then, personal finance is the application of financial principles to the monetary decisions that you make either for your individual benefit or for that of your family.

Second, as we suggested earlier, monetary decisions work out much more beneficially when they’re planned rather than improvised. Thus our emphasis on financial planning—the ongoing process of managing your personal finances in order to meet goals that you’ve set for yourself or your family.

Financial planning requires you to address several questions, some of them relatively simple:

- What’s my annual income?

- How much debt do I have, and what are my monthly payments on that debt?

Others will require some investigation and calculation:

- What’s the value of my assets?

- How can I best budget my annual income?

Still others will require some forethought and forecasting:

- How much wealth can I expect to accumulate during my working lifetime?

- How much money will I need when I retire?

The Financial Planning Life Cycle

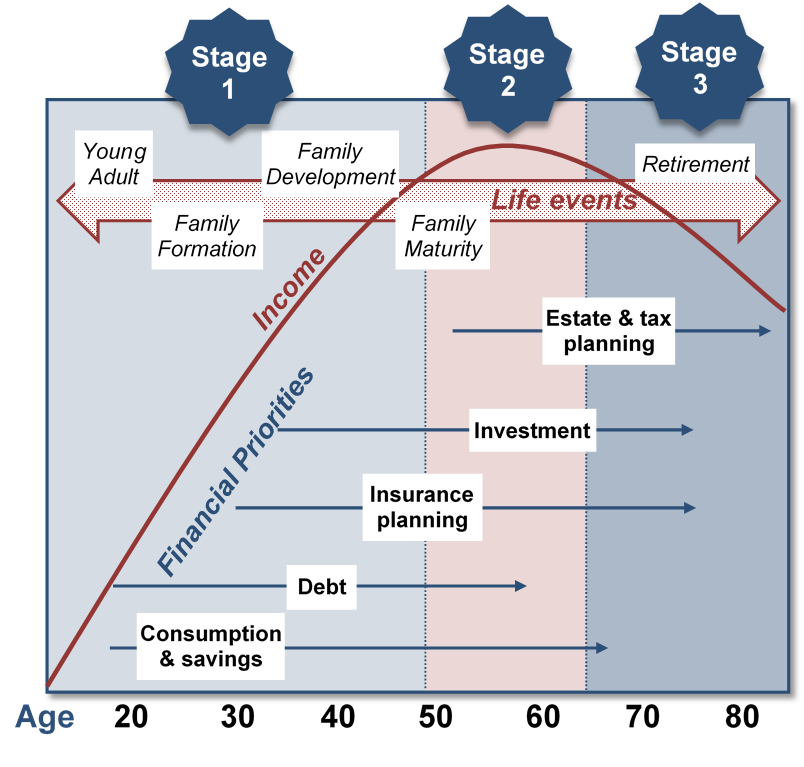

Another question that you might ask yourself—and certainly would do if you worked with a professional in financial planning—is: “How will my financial plans change over the course of my life?” The figure below illustrates the financial life cycle of a typical individual—one whose financial outlook and likely outcomes are probably a lot like yours.[7] As you can see, our diagram divides this individual’s life into three stages, each of which is characterized by different life events (such as beginning a family, buying a home, planning an estate, retiring).

At each stage, there are recommended changes in the focus of the individual’s financial planning:

- Stage 1 focuses on building wealth.

- Stage 2 shifts the focus to the process of preserving and increasing wealth that one has accumulated and continues to accumulate.

- Stage 3 turns the focus to the process of living on (and, if possible, continuing to grow) one’s saved wealth after retirement.

At each stage, of course, complications can set in—changes in such conditions as marital or employment status or in the overall economic outlook, for example. Finally, as you can also see, your financial needs will probably peak somewhere in stage 2, at approximately age fifty-five, or ten years before typical retirement age.

Choosing a Career

Until you’re on your own and working, you’re probably living on your parents’ wealth right now. In our hypothetical life cycle, financial planning begins in the individual’s early twenties. If that seems like rushing things, consider a basic fact of life: this is the age at which you’ll be choosing your career—not only the sort of work you want to do during your prime income-generating years, but also the kind of lifestyle you want to live. What about college? Most readers of this book, of course, have decided to go to college. If you haven’t yet decided, you need to know that college is an extremely good investment of both money and time.

The figure below summarizes the most recent, 2015, findings from Statistics Canada.[8] A quick review shows that people who graduate from high school can expect to enjoy average annual earnings of just under $50,000, and those who go on to finish college can expect to generate 17 percent more annual income than high school graduates who didn’t attend college. With better access to health care—and, studies show, with better dietary and health practices—college graduates will also live longer. And so will their children.)[9]

| Education | Average Income: Canadian Women | Average Income: Canadian Men |

| High school diploma | $43,254 | $55,774 |

| College diploma | $48,599 | $67,965 |

| Bachelor’s degree | $68,342 | $82,082 |

What about the student-loan debt that so many people accumulate? At an average cost of $27,000 (the average amount of debt accumulated by post-secondary students upon graduation) and an average increase in earnings of $263,000 over an average work-life expectancy of 30 years, you would need to invest that $27,000 for 30 years at an average annual rate of return of 8%.[10] At that rate of return, you should be able to pay off your student loans (unless, of course, you fail to practice reasonable financial planning).

Naturally, there are exceptions to these average outcomes. You’ll find some college graduates stocking shelves at 7-Eleven, and you’ll find college dropouts running multibillion-dollar enterprises. Microsoft co-founder Bill Gates dropped out of college after two years, as did his founding partner, Paul Allen. Though exceptions to rules (and average outcomes) certainly can be found, they fall far short of disproving them: in entrepreneurship as in most other walks of adult life, the better your education, the more promising your financial future. One expert in the field puts the case for the average person bluntly: educational credentials “are about being employable, becoming a legitimate candidate for a job with a future. They are about climbing out of the dead-end job market”.[11]

Bringing Down Those Monthly Bills

So to be able to practice reasonable financial planning you must first be able to identify how you can bring down your monthly bills? If you want to take a gradual approach, one financial planner suggests that you perform the following “exercises” for one week:[12]

- Keep a written record of everything you spend and total it at week’s end.

- Keep all your ATM receipts and count up the fees.

- Take $100 out of the bank and don’t spend a penny more.

- Avoid gourmet coffee shops.

You’ll probably be surprised at how much of your money can quickly become somebody else’s money. If, for example, you spend $3 every day for one cup of coffee at a coffee shop, you’re laying out nearly $1,100 a year just for coffee. If you use your ATM card at a bank other than your own, you’ll probably be charged a fee that can be as high as $3. The average person pays more than $60 a year in ATM fees. If you withdraw cash from an ATM twice a week, you could be racking up $300 in annual fees.[13] Another idea – eat out as a reward, not as a rule. A sandwich or leftovers from home can be just as tasty and can save you $6 to $10 a day, even more than our number for coffee! In 2013, the website DailyWorth asked three women to try to cut their spending in half. After tracking her spending, one participant discovered that she had spent $175 eating out in just one week; do that for a year and you’d spend over $9,000![14] If you think your cable bill is too high, consider alternatives like Playstation Vue or Sling. Changing channels is a bit different, but the savings can be substantial.

You may or may not be among the Canadian consumers who purchased more than 3 billion cans, 2 billion bottles and 40 million kegs of beer, in 2016 alone, or purchased one or more of the over 2 billion Tim Hortons coffees sold each year. You may not be one of the 37% percent of Canadian consumers that regret spending outside of your means.[15] Bottom line – if, at age twenty-eight, you have a good education and a good job, a $60,000 income, and $70,000 in debt—by no means an implausible scenario—there’s a very good reason why you should think hard about controlling your debt: your level of indebtedness will be a key factor in your ability—or inability—to reach your longer-term financial goals, such as home ownership, a dream trip, and, perhaps most importantly, a reasonably comfortable retirement.

One of the best ways to manage your money and personal finances is to build a personal budget.

Personal budget

Personal budget

You will need to have all your information gathered. This includes what you bring in – from employment to student loans – and what goes out – for food, entertainment, health and wellness, rent, utilities, etc. Be honest and thorough.

The Government of Canada, through the Financial Agency of Canada, created a tool that provides an in-depth account of your personal finances. Use the Budget Calculator to document your situation. Export your budget as an Excel spreadsheet. You will now be able to make improvements, if appropriate. If your balance is negative, or when your expenses exceed your income, you need to make some choices based on what you learned when you tracked your spending. Ask yourself some tough questions:

- What can be eliminated from my expenses?

- What can be reduced from my expenses?

- In what areas can I be a smarter consumer?

- Where does my money seem to get gobbled up?

After you have made some difficult choices, turn back to the budget worksheet and create a new “revised” column. You will want to work toward achieving a positive balance.

Should you end up with a surplus or positive balance, you need to make some choices about what to do with the extra money. Perhaps you could put it toward your financial SMARTER goal. Avoid the temptation to spend it.

Now let’s suppose that while browsing through a magazine in the doctor’s office, you run across a short personal-finances self-help quiz. There are six questions (recreated here):

You took the quiz and added your response values.

Personal-finances experts tend to utilize the types of questions on the quiz: if you had 1s or 2s on any of the first three questions, you have a problem with splurging; if any questions from four through six got 1s or 2s, your monthly bills are too high for your income.

Building a Good Credit Rating

So, you may or may not have a financial problem. According to the quick test you took, do you splurge? Are your bills too high for your income? If you get in over your head and can’t make your loan or rent payments on time, you risk hurting your credit rating—your ability to borrow in the future.

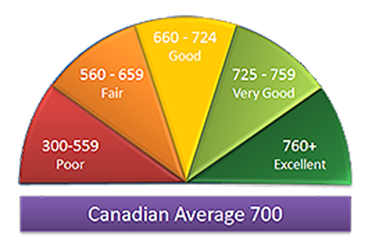

How do potential lenders decide whether you’re a good or bad credit risk? If you’re a poor credit risk, how does this affect your ability to borrow, or the rate of interest you have to pay? Whenever you use credit, those from whom you borrow (retailers, credit card companies, banks) provide information on your debt and payment habits to two national credit bureaus: Equifax, and TransUnion. The credit bureaus use the information to compile a numerical credit score, called a FICO score; it ranges from 300 to 900, with the majority of people falling in the 600–700 range. In compiling the score, the credit bureaus consider five criteria: However, the main factors that are used to calculate your score include:

- Payment history

- Use of available credit

- Length of credit history

- Number of inquiries

- Types of credit

The credit bureaus share their score and other information about your credit history with their subscribers.[16]

So what does this do for you? It depends. If you pay your bills on time and don’t borrow too heavily, you’d likely have a high FICO score and lenders would like you, probably giving you reasonable interest rates on the loans you requested. But if your FICO score is low, lenders won’t likely lend you money (or would lend it to you at high interest rates). A low FICO score can even affect your chances of renting an apartment or landing a particular job. So it’s very important that you do everything possible to earn and maintain a high credit score.

As a young person, though, how do you build a credit history that will give you a high FICO score? Based on feedback from several financial experts, Emily Starbuck Gerson and Jeremy Simon of CreditCards.com compiled the following list of ways students can build good credit.[17]

- Become an authorized user on a parent’s account.

- Obtain your own credit card.

- Get the right card for you.

- Use the credit card for occasional, small purchases.

- Avoid big-ticket buys, except in case of emergency.

- Pay off your balance each month.

- Pay all your other bills on time.

- Don’t cosign for your friends.

- Don’t apply for several credit cards at one time.

- Use student loans for education expenses only, and pay on time.

If you meet the qualifications to obtain your own credit card, look for a card with a low interest rate and no annual fee.

A Few More Words about Debt

What should you do to turn things around—to start getting out of debt? According to many experts, you need to take two steps:

- Cut up your credit cards and start living on a cash-only basis.

- Do whatever you can to bring down your monthly bills.

Although credit cards can be an important way to build a credit rating, many people simply lack the financial discipline to handle them well. If you see yourself in that statement, then moving to a pay-as-you go basis, i.e., cash or debit card only, may be for you. Be honest with yourself; if you can’t handle credit, then don’t use it.

Banking

Suppose you want to save or invest – do you know how or where to do so? You probably know that your branch bank can open a savings account for you, but interest rates on such accounts can be pretty unattractive. Investing in individual stocks or bonds can be risky, and usually require a level of funds available that most students don’t have. In those cases, mutual funds can be quite interesting. A mutual fund is a professionally managed investment program in which shareholders buy into a group of diversified holdings, such as stocks and bonds. Any of the big 5 banks in Canada (RBC, CIBC, BMO, TDCanada, or Scotiabank) offer a range of investment options including indexed funds, which track with well-known indices such as the Toronto Stock Exchange, a.k.a. the TSX. Minimum investment levels in such funds can actually be within the reach of many students, and the funds accept electronic transfers to make investing more convenient.

We’ll leave a more detailed discussion of investment vehicles to your more advanced courses.

You may choose to do your banking with a major bank, or with a local credit union. Most people never notice the differences between credit unions and banks. They offer similar products and services, but they’re not the same. The following are some key points which highlight the differences:

Major Banks:

- Funds are secure

- Profitability– usually shareholders own a bank and expect financial performance from bank management

- Offer a wide range of competitive and advanced banking products

- Inter-branch banking = convenience

Credit Unions:

- Customers are “members”; deposits are called “shares”

- Credit Unions are non-profit organizations that strive for service over profitability. They are NOT charities; credit unions must make sound financial decisions, collect revenue, pay salaries, and compete with other institutions.

- May not have all the banking products as major banks

- Inter-branch banking is limited

- Funds are also secure

Choose an Institution that is Right for You

As a college or university student, you might be out on your own for the first time. Part of handling your own finances will be choosing a banking institution or institutions that best suit your needs. Banks are eager to gain new clientele and establish brand loyalty early on. It should come as no surprise, then, that just about every major banking institution in Canada offers student-banking plans.

Now you are ready to start planning for your financial future.

Key Takeaways

Important terms and concepts

- Credit worthiness is measured by the FICO score – or credit rating – which can range from 300-850. The average ranges from 680-719.

- To maintain a satisfactory score, pay your bills on time, borrow only when necessary, and pay in full whenever you do borrow.

- 81% of financial planners recommend eating out less as a way to reduce your expenses.

- Personal finance is the application of financial principles to the monetary decisions that you make.

- Financial planning is the ongoing process of managing your personal finances in order to meet your goals, which vary by stage of life.

- Time value of money is the principle that a dollar received in the present is worth more than a dollar received in the future due to its potential to earn interest.

- Compound interest refers to the effect of earning interest on your interest. It is a powerful way to accumulate wealth.