This section looks at the difference between mental health and mental illness and introduces the Mental Health Continuum, which illustrates how we can all move from healthier to more disrupted levels of functioning and back.

This section also looks at marginalized groups that are at higher risk of experiencing mental health challenges and face greater barriers to getting help.

These slides are available for use with this section of the presentation. For information about downloading presentation slides, see Introduction.

Mental Health and Mental Illness

Mental health is a term that is often used interchangeably with mental health issues or mental illness, but they are not the same.

As we discussed, mental health is the capacity of every individual to feel, think, and act in ways that enhance their ability to enjoy life and deal with challenges.

Mental health issues refer to diminished capacities – whether cognitive, emotional, attentional, interpersonal, motivational, or behavioural – that interfere with a person’s enjoyment of life or adversely affect interactions with society and environment. Feelings of low self-esteem, frequent frustration or irritability, burnout, feelings of stress, or excessive worrying, are all examples of common mental health problems.[1] Most people will experience mental health issues like these at some point in their life.

Mental illnesses are conditions that affect a person’s thinking, feeling, mood, or behaviour, such as depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia. Such conditions may be occasional or long-lasting (chronic) and affect someone’s ability to relate to others and function each day.

Mental health is more than the absence of mental illness. It includes our emotional, psychological, and social well-being. It is influenced by many factors, and it affects how we handle the normal stresses of life and relate to others.

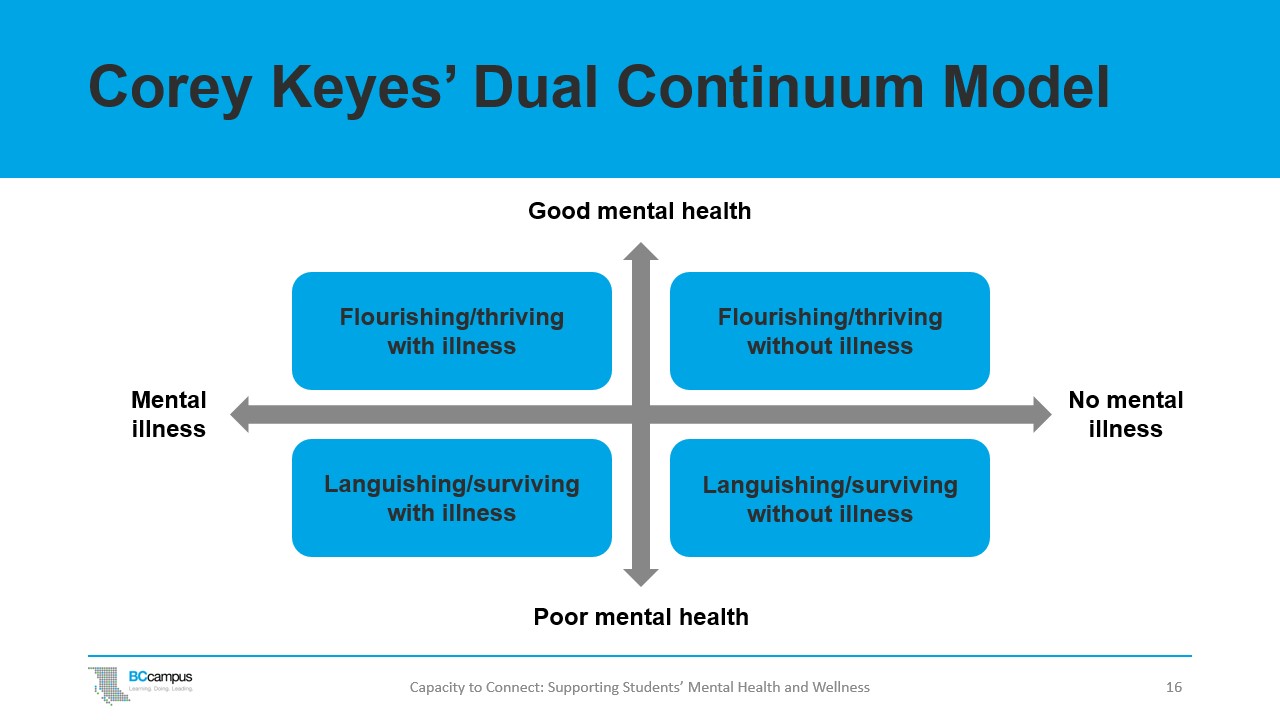

A person diagnosed with a mental illness can have good mental health and be flourishing and thriving. Likewise, a person can be languishing or experiencing poor mental health and not be diagnosed with a mental illness. The Corey Keyes Dual Continuum Model illustrates this.

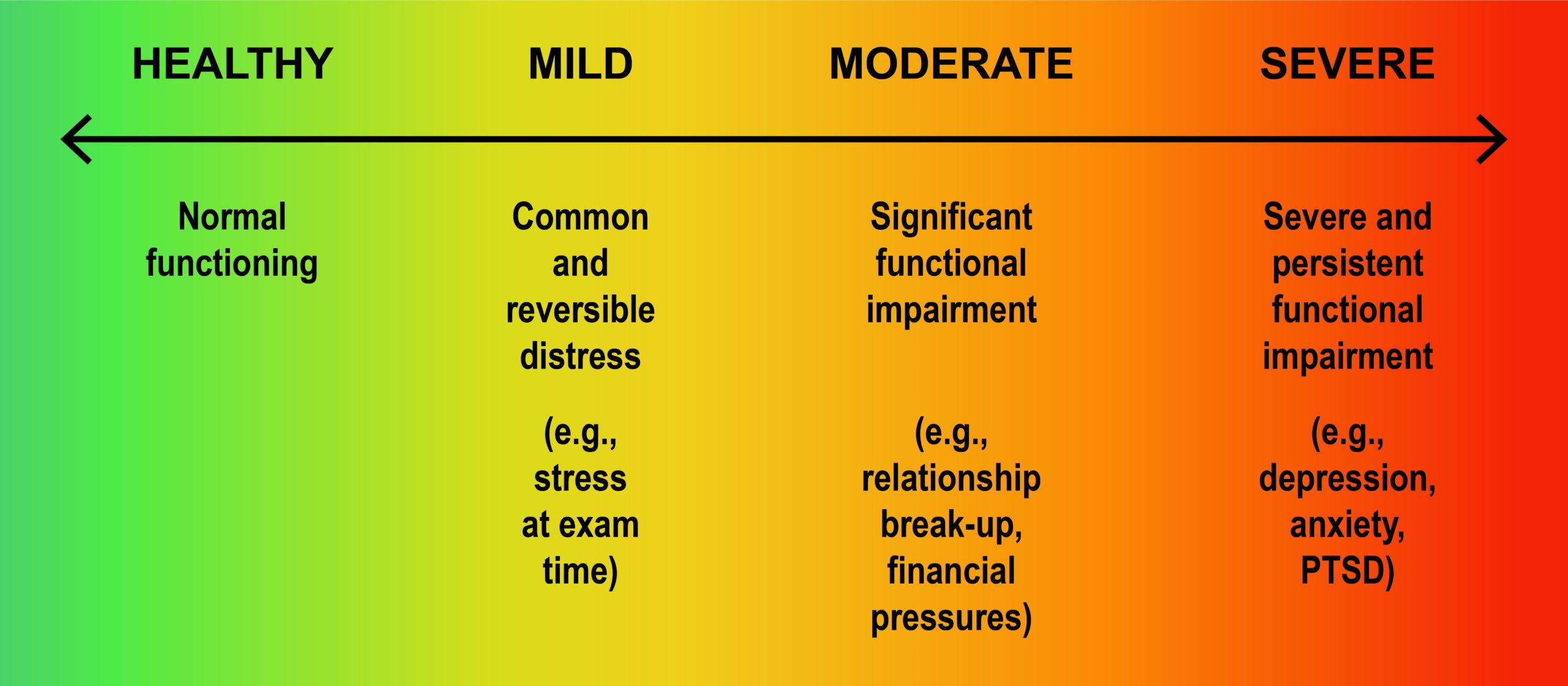

Mental Health Continuum

The Mental Health Continuum is another way to think about mental health. All of us have a mental health life; we all experience changes in our mood, changes in our level of anxiety – from life stressors or from crises – and those changes can be considered on a spectrum or a continuum. On this continuum, we can move from healthier to more disrupted levels of functioning and back. At each level, there are resources to promote health and reduce disruption.

Healthy

On one end of the continuum, we have times when our health is good, we can cope with whatever comes our way, and we can do the things we need or want to do. We would describe that as healthy functioning. Thinking back to the Wellness Wheel, this is when everything is mostly in balance on the wheel or in our lives.

Mild Disruption

There are moments in our lives when we have what we call predictable or common stress. These experiences of stress are to be expected at times in our lives – they may be common and reversible, and they are usually temporary, such as the stress students experience during exam time. Students can maintain hope that when it’s all over, they’ll likely feel a lot better – the stressor will come to end and there is usually some relief.

We all have times when we feel down or stressed or frightened. Most of the time those feelings pass. Sometimes a person may just need someone to talk to and to be reminded that they are resilient and have other strengths, even though they may be struggling in one part of their life.

Moderate Disruption

The next level is moderate disruption, which signifies more severe impairment to one’s mental health. Here the disruption is becoming more serious, and it is affecting other parts of a person’s life and their ability to function. A relationship break-up or financial pressures could cause more moderate disruption. On the Wellness Wheel, several areas of wellness are impaired and there is a more serious imbalance.

Severe Disruption

Severe disruption is when a person is unable to cope on their own because of significant and persistent functional impairment. They may need to take time off, and to seek professional help from a counsellor, doctor, or the hospital because of a mental illness such as anxiety, depression, or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Marginalized Groups and Mental Health

When we talk about mental health, we also need to be aware of factors like race, sexual orientation, social class, age, disability, and gender and the unique life experiences and stressors that accompany them. Some students face inequality, discrimination, and violence because of their race, gender orientation, or disability. These unique and specific stressors impact mental and physical health, and these students often experience greater mental health burdens and face more barriers to accessing care.

By providing a culturally safe environment, we can all play a role to ensure that each student feels their personal, social, and cultural identity is respected and valued.

International Students

Both undergraduate and graduate international students are often under a lot of pressure and the stakes are often very high for them. Their tuition is expensive, they’ve travelled a long way to attend a post-secondary institution in B.C., and they feel a lot of pressure to do well academically. They may be struggling to adjust to a new culture or learn English, and they may be missing home, family, and friends. The understanding of mental health and wellness differs between cultures, and international students may have a different understanding of how mental health impacts academic performance, and they may not be aware of the support systems available to them when they arrive.

Indigenous Students

Indigenous students may be struggling as they adjust from living in a community where they are surrounded by family and neighbours who share the same culture and spiritual beliefs to living in an urban academic setting. They may be the first generation to pursue post-secondary education, and they may be missing their home, family, Elders, and community. The impact of residential schools and other colonial policies have created ongoing adversity for Indigenous people, and there is evidence that this has created intergenerational trauma. Many Indigenous students may also lack trust in educational and health care institutions because of the negative or traumatic experiences they or family and friends have experienced in the past.

LGBTQ2S+ Students

People who are LGBTQ2S+ (lesbian, gay, bi-sexual, transgender, queer, Two-Spirit) are at a much higher risk than the general population for mental health disorders, substance abuse, and suicide.[2] Homophobia and negative stereotypes about being LGBTQ2S+ can make it challenging for a student to let people know this important part of their identity. When people do openly express this part of themselves, they worry about the potential of rejection from peers, colleagues, and friends, and this can exacerbate feelings of loneliness. Their health needs may be unique and complex, and health care settings can feel unsafe or uncomfortable for some.

Students with a Disability

Many students live with some form of physical, cognitive, sensory, mental health, or other disability. Students of all abilities and backgrounds deserve post-secondary settings that are inclusive and respectful. Unfortunately, many institutions are not designed to fully support people who need extra accommodation, and students with a disability frequently encounter accessibility challenges and extra barriers to achieving academic success. In addition to navigating the complex environment of a post-secondary institution that is not set up for them, students with a disability also often have to combat negative stereotypes, bias, and discrimination. These many extra challenges can take their toll on mental health.

Racialized Students

Black, Indigenous, and other racialized students have likely faced racism and discrimination multiple times throughout their lives. Racism can encompass a range of words and actions, from the overt racism of violence or slurs to microaggressions (everyday, subtle interactions that demean or put down a person based on their race). Sometimes microaggressions are not intentional, but they can still be very harmful, and they are a form of racism that many students experience. These repeated negative interactions can be overwhelming at times, especially in post-secondary spaces where a student could reasonably assume they would be free from any form of bullying, harassment, or discrimination.

Racism and discrimination in various forms can have a significant impact on a student’s mental health and can lead to increased risk of depression or suicide, increased levels of anxiety and stress-related illnesses, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

Reflection Activity

Ask participants to think about the students they work with and consider the stresses that may be specific to certain groups.

Text Attributions

- This chapter was adapted from Capacity to Connect: Supporting Students in Distress © Vancouver Island University. Added “Mental Health and Mental Illness,” “Continuum of Mental Health,” “Marginalized Groups and Mental Health.” Adapted by Barbara Johnston. CC BY 4.0 license.

Media Attributions

- Dual-Continuum Model © BCcampus based on the conceptual work of Corey Keys and a diagram created by CACUSS and Canadian Mental Health Association is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 license.

- Mental Health Continuum model, based on the University of Victoria continuum of mental health, which is adapted from on Queen’s University continuum of mental health and the Canada Department of National Defence continuum of mental health.

- Icon on slide 6. reflections of the heart by www.mindgraphy.com, ES In the Heart and love 2 Collection, from the Noun Project is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 license.

- Stephens, T., Dulberg, C., & Joubert, N. (1999). Mental health of the Canadian population: A comprehensive analysis. Chronic Diseases in Canada, 20(3): 118–126. ↵

- U.S. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (n.d.). Healthy people 2020: Lesbian, gay, and transgender health. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/lesbian-gay-bisexual-and-transgender-health ↵