1.1 Understanding Organizational Behavior

Learning Objectives

- Understand what organizational behaviour is.

- Explore notions of work and organization.

- Understand why organizational behaviour matters.

- Learn about OB Toolboxes in this book.

The people make the place.

Throughout this course we will share many examples of people making their workplaces work. People can make work an exciting, fun, and productive place to be, or they can make it a routine, boring, and ineffective place where everyone dreads to go. Steve Jobs, cofounder, chairman, and CEO of Apple Inc. attributes the innovations at Apple, which include the iPod, MacBook, and iPhone, to people, noting, “Innovation has nothing to do with how many R&D dollars you have.…It’s not about money. It’s about the people you have, how you’re led, and how much you get it”[1]. This became a sore point with investors in early 2009 when Jobs took a medical leave of absence. Many wonder if Apple will be as successful without him at the helm, and Apple stock plunged upon worries about his health.[2]

Mary Kay Ash, founder of Mary Kay Inc., a billion-dollar cosmetics company, makes a similar point, saying, “People are definitely a company’s greatest asset. It doesn’t make any difference whether the product is cars or cosmetics. A company is only as good as the people it keeps”[3]

Just like people, organizations come in many shapes and sizes. We understand that the career path you will take may include a variety of different organizations. In addition, we know that each student reading this book has a unique set of personal and work-related experiences, capabilities, and career goals. The Great Resignation is in full swing and impacting employers across the country. A recent survey conducted by Randstad and Ipsos shows that 36% of blue-collar workers and 21% of white-collar workers in Canada have changed jobs within the last 12 months.[4]. In order to succeed in this type of career situation, individuals need to be armed with the tools necessary to be lifelong learners. So, this book will not be about giving you all the answers to every situation you may encounter when you start your first job or as you continue up the career ladder. Instead, this book will give you the vocabulary, framework, and critical thinking skills necessary for you to diagnose situations, ask tough questions, evaluate the answers you receive, and act in an effective and ethical manner regardless of situational characteristics.

Throughout this book, when we refer to organizations, we will include examples that may apply to diverse organizations such as publicly held, for-profit organizations like Google and American Airlines, privately owned businesses such as S. C. Johnson & Son Inc. (makers of Windex glass cleaner) and Mars Inc. (makers of Snickers and M&Ms), and not-for-profit organizations such as the Sierra Club or Mercy Corps, and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) such as Doctors Without Borders and the International Red Cross. We will also refer to both small and large corporations. You will see examples from Fortune 500 organizations such as Intel Corporation or Home Depot Inc., as well as small start-up organizations. Keep in mind that some of the small organizations of today may become large organizations in the future. For example, in 1998, eBay Inc. had only 29 employees and $47.4 million in income, but by 2008 they had grown to 11,000 employees and over $7 billion in revenue.[5] Regardless of the size or type of organization you may work for, people are the common denominator of how work is accomplished within organizations.

Together, we will examine people at work both as individuals and within work groups and how they impact and are impacted by the organizations where they work. Before we can understand these three levels of organizational behaviour, we need to agree on a definition of organizational behaviour.

What is Work?[6]

Some people live to work, while others simply work to live. In any case, people clearly have strong feelings about what they do on the job and about the people with whom they work. In our study of behaviour in organizations, we shall examine what people do, what causes them to do it, and how they feel about what they do. As a prelude to this analysis, however, we should first consider the basic unit of analysis in this study: work itself. What is work, and what functions does it serve in today’s society?

Work has a variety of meanings in contemporary society. Often we think of work as paid employment—the exchange of services for money. Although this definition may suffice in a technical sense, it does not adequately describe why work is necessary. Perhaps work could be more meaningfully defined as an activity that produces something of value for other people. This definition broadens the scope of work and emphasizes the social context in which the wage-effort bargain transpires. It clearly recognizes that work has purpose—it is productive. Of course, this is not to say that work is necessarily interesting or rewarding or satisfying. On the contrary, we know that many jobs are dull, repetitive, and stressful. Even so, the activities performed do have utility for society at large. One of the challenges of management is to discover ways of transforming necessary yet distasteful jobs into more meaningful situations that are more satisfying and rewarding for individuals and that still contribute to organizational productivity and effectiveness.

Functions of Work[7]

We know why work activities are important from an organization’s viewpoint. Without work there is no product or service to provide. But why is work important to individuals? What functions does it serve?

First, work serves a rather obvious economic function. In exchange for labour, individuals receive necessary income with which to support themselves and their families. But people work for many reasons beyond simple economic necessity.

Second, work also serves several social functions. The workplace provides opportunities for meeting new people and developing friendships. Many people spend more time at work with their co-workers than they spend at home with their own families.

Third, work also provides a source of social status in the community. One’s occupation is a clue to how one is regarded on the basis of standards of importance prescribed by the community. For instance, in the United States a corporate president is generally accorded greater status than a janitor in the same corporation. In China, on the other hand, great status is ascribed to peasants and people from the working class, whereas managers are not so significantly differentiated from those they manage. In Japan, status is first a function of the company you work for and how well-known it is, and then the position you hold. It is important to note here that the status associated with the work we perform often transcends the boundaries of our organization. A corporate president or a university president may have a great deal of status in the community at large because of his position in the organization. Hence, the work we do can simultaneously represent a source of social differentiation and a source of social integration.

Fourth, work can be an important source of identity and self-esteem and, for some, a means for self-actualization. It provides a sense of purpose for individuals and clarifies their value or contribution to society. As Freud noted long ago, “Work has a greater effect than any other technique of living in binding the individual more closely to reality; in his work he is at least securely attached to a part of reality, the human community.”[8]

Work contributes to self-esteem in at least two ways. First, it provides individuals with an opportunity to demonstrate competence or mastery over themselves and their environment. Individuals discover that they can actually do something. Second, work reassures individuals that they are carrying out activities that produce something of value to others—that they have something significant to offer. Without this, the individual feels that they have little to contribute and is thus of little value to society.

We clearly can see that work serves several useful purposes from an individual’s standpoint. It provides a degree of economic self-sufficiency, social interchange, social status, self-esteem, and identity. Without this, individuals often experience sensations of powerlessness, meaninglessness, and normlessness—a condition called alienation. In work, individuals have the possibility of finding some meaning in their day-to-day activities—if, of course, their work is sufficiently challenging.

When employees are not involved in their jobs because the work is not challenging enough, they usually see no reason to apply themselves, which, of course, jeopardizes productivity and organizational effectiveness. This self-evident truth has given rise to a general concern among managers about declining productivity and work values. In fact, concern about this situation has caused many managers to take a renewed interest in how the behavioural sciences can help them solve many of the problems of people at work.

What Is Organizational Behavior?

Organizational behaviour (OB) is defined as the systematic study and application of knowledge about how individuals and groups act within the organizations where they work. As you will see throughout this book, definitions are important. They are important because they tell us what something is as well as what it is not. For example, we will not be addressing childhood development in this course—that concept is often covered in psychology—but we might draw on research about twins raised apart to understand whether job attitudes are affected by genetics.

OB draws from other disciplines to create a unique field. As you read this book, you will most likely recognize OB’s roots in other disciplines. For example, when we review topics such as personality and motivation, we will again review studies from the field of psychology. The topic of team processes relies heavily on the field of sociology. In the chapter relating to decision making, you will come across the influence of economics. When we study power and influence in organizations, we borrow heavily from political sciences. Even medical science contributes to the field of organizational behaviour, particularly to the study of stress and its effects on individuals.

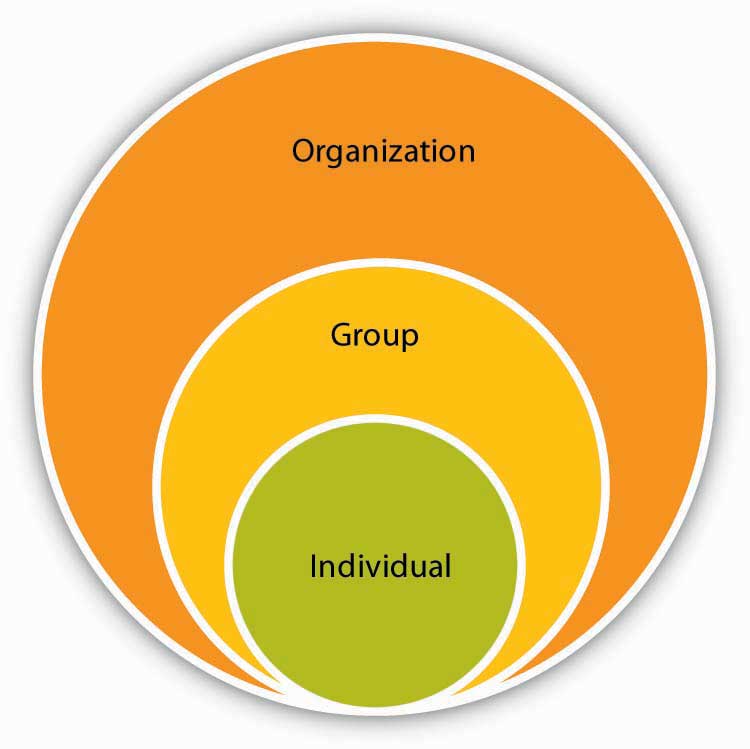

Those who study organizational behaviour—which now includes you—are interested in several outcomes such as work attitudes (e.g., job satisfaction and organizational commitment) as well as job performance (e.g., customer service and counterproductive work behaviours). A distinction is made in OB regarding which level of the organization is being studied at any given time. There are three key levels of analysis in OB. They are examining the individual, the group, and the organization. For example, if I want to understand my boss’s personality, I would be examining the individual level of analysis. If we want to know about how my manager’s personality affects my team, I am examining things at the team level. But, if I want to understand how my organization’s culture affects my boss’s behaviour, I would be interested in the organizational level of analysis. The study of the behaviour of people in organizations is typically referred to as organizational behaviour. Here, the focus is on applying what we can learn from the social and behavioural sciences so we can better understand and predict human behaviour at work.

We examine such behaviour on three levels—the individual, the group, and the organization as a whole. In all three cases, we seek to learn more about what causes people—individually or collectively—to behave as they do in organizational settings. What motivates people? What makes some employees leaders and others not? Why do groups often work in opposition to their employer? How do organizations respond to changes in their external environments? How do people communicate and make decisions? Questions such as these constitute the domain of organizational behaviour and are the focus of this course.To a large extent, we can apply what has been learned from psychology, sociology, and cultural anthropology. In addition, we can learn from economics and political science. All of these disciplines have something to say about life in organizations. However, what sets organizational behaviour apart is its particular focus on the organization (not the discipline) in organizational analysis. Thus, if we wish to examine a problem of employee motivation, for example, we can draw upon economic theories of wage structures in the workplace.

At the same time, we can also draw on the psychological theories of motivation and incentives as they relate to work. We can bring in sociological treatments of social forces on behaviour, and we can make use of anthropological studies of cultural influences on individual performance. It is this conceptual richness that establishes organizational behaviour as a unique applied discipline. And throughout our analyses, we are continually concerned with the implications of what we learn for the quality of working life and organizational performance. We always look for management implications so the managers of the future can develop more humane and more competitive organizations for the future.

For convenience, we often differentiate between micro- and macro-organizational behaviour. Micro-organizational behaviour is primarily concerned with the behaviour of individuals and groups, while macro-organizational behaviour (also referred to as organization theory) is concerned with organization-wide issues, such as organization design and the relations between an organization and its environment.

Why Organizational Behavior Matters

OB matters at three critical levels. It matters because it is all about things you care about. OB can help you become a more engaged organizational member. Getting along with others, getting a great job, lowering your stress level, making more effective decisions, and working effectively within a team…these are all great things, and OB addresses them!

It matters because employers care about OB. A recent survey by the National Association of Colleges and Employers (NACE) asked employers which skills are the most important for them when evaluating job candidates, and OB topics topped the list.[9]

The following were the top five personal qualities/skills:

- Communication skills (verbal and written)

- Honesty/integrity

- Interpersonal skills (relates well to others)

- Motivation/initiative

- Strong work ethic

These are all things we will cover in OB.

Finally, it matters because organizations care about OB. The best companies in the world understand that the people make the place. How do we know this? Well, we know that organizations that value their employees are more profitable than those that do not.[10] [11][12][13]Research shows that successful organizations have a number of things in common, such as providing employment security, engaging in selective hiring, utilizing self-managed teams, being decentralized, paying well, training employees, reducing status differences, and sharing information.[14]

For example, every Whole Foods store has an open compensation policy in which salaries (including bonuses) are listed for all employees. There is also a salary cap that limits the maximum cash compensation paid to anyone in the organization, such as a CEO, in a given year to 19 times the companywide annual average salary of all full-time employees. What this means is that if the average employee makes $30,000 per year, the highest potential pay for their CEO would be $570,000, which is a lot of money but pales in comparison to salaries such as Steve Jobs of Apple at $14.6 million or the highest paid CEO in 2007, Larry Ellison of Oracle, at $192.9 million.[15]

Research shows that organizations that are considered healthier and more effective have strong OB characteristics throughout them such as role clarity, information sharing, and performance feedback. Unfortunately, research shows that most organizations are unhealthy, with 50% of respondents saying that their organizations do not engage in effective OB practices.[16]

In the rest of this chapter, we will build on how you can use this book by adding tools to your OB Toolbox in each section of the book as well as assessing your own learning style. In addition, it is important to understand the research methods used to define OB, so we will also review those. Finally, you will see what challenges and opportunities businesses are facing and how OB can help overcome these challenges.

Adding to Your OB Toolbox

Your OB Toolbox

OB Toolboxes appear throughout this book. They indicate a tool that you can try out today to help you develop your OB skills.

Throughout the book, you will see many OB Toolbox features. Our goal in writing this book is to create something useful for you to use now and as you progress through your career. Sometimes we will focus on tools you can use today. Other times we will focus on things you may want to think about that may help you later. As you progress, you may discover some OB tools that are particularly relevant to you while others are not as appropriate at the moment. That’s great—keep those that have value to you. You can always go back and pick up tools later on if they don’t seem applicable right now.

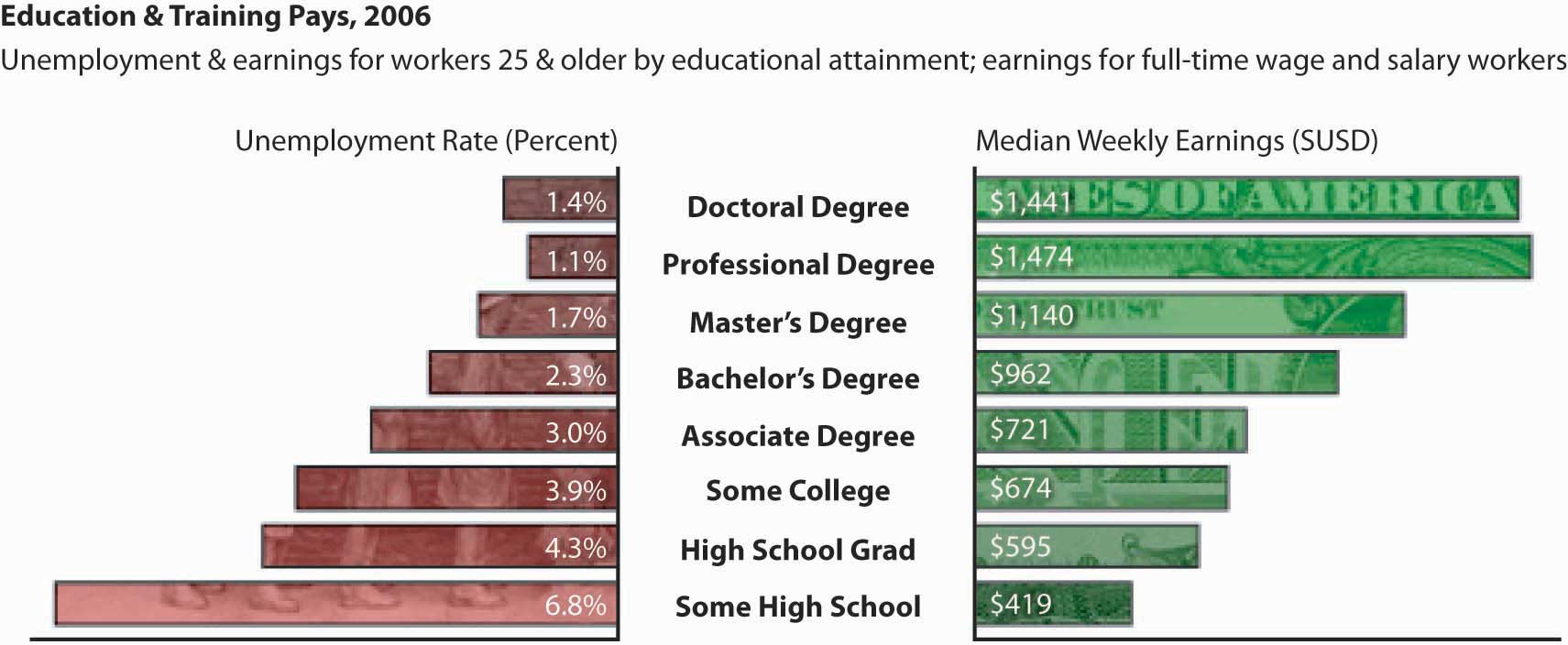

The important thing to keep in mind is that the more tools and skills you have, the higher the quality of your interactions with others will be and the more valuable you will become to organizations that compete for top talent.[17] It is not surprising that, on average, the greater the level of education you have, the more money you will make. In 2006, those who had a college degree made 62% more money than those who had a high school degree (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics). Organizations value and pay for skills as the next figure shows. Figure 1.4[18]

Tom Peters is a management expert who talks about the concept of individuals thinking of themselves as a brand to be managed. Further, he recommends that individuals manage themselves like free agents.[19]The following OB Toolbox includes several ideas for being effective in keeping up your skill set.

Your OB Toolbox: Skill Survival Kit

- Keep your skills fresh. Consider revolutionizing your portfolio of skills at least every 6 years.

- Master something. Competence in many skills is important, but excelling at something will set you apart.

- Embrace ambiguity. Many people fear the unknown. They like things to be predictable. Unfortunately, the only certainty in life is that things will change. Instead of running from this truth, embrace the situation as a great opportunity.

- Network. The term has been overused to the point of sounding like a cliché, but networking works. This doesn’t mean that having 200 connections on MySpace, LinkedIn, or Facebook makes you more effective than someone who has 50, but it does mean that getting to know people is a good thing in ways you can’t even imagine now.

- Appreciate new technology. This doesn’t mean you should get and use every new gadget that comes out on the market, but it does mean you need to keep up on what the new technologies are and how they may affect you and the business you are in.[20]

A key step in building your OB skills and filling your toolbox is to learn the language of OB. Once you understand a concept, you are better able to recognize it. Once you recognize these concepts in real-world events and understand that you have choices in how you will react, you can better manage yourself and others. An effective tool you can start today is journaling, which helps you chart your progress as you learn new skills. For more on this, see the OB Toolbox below.

OB Toolbox: Journaling as a Developmental Tool

- What exactly is journaling? Journaling refers to the process of writing out thoughts and emotions on a regular basis.

- Why is journaling a good idea? Journaling is an effective way to record how you are feeling from day to day. It can be a more objective way to view trends in your thoughts and emotions so you are not simply relying on your memory of past events, which can be inaccurate. Simply getting your thoughts and ideas down has been shown to have health benefits as well such as lowering the writer’s blood pressure, heart rate, and decreasing stress levels.

- How do I get started? The first step is to get a journal or create a computer file where you can add new entries on a regular basis. Set a goal for how many minutes per day you want to write and stick to it. Experts say at least 10 minutes a day is needed to see benefits, with 20 minutes being ideal. The quality of what you write is also important. Write your thoughts down clearly and specifically while also conveying your emotions in your writing. After you have been writing for at least a week, go back and examine what you have written. Do you see patterns in your interactions with others? Do you see things you like and things you’d like to change about yourself? If so, great! These are the things you can work on and reflect on. Over time, you will also be able to track changes in yourself, which can be motivating as well.[21]

Isn’t OB Just Common Sense?

As teachers we have heard this question many times. The answer, as you might have guessed, is no—OB is not just common sense. As we noted earlier, OB is the systematic study and application of knowledge about how individuals and groups act within the organizations where they work. Systematic is an important word in this definition. It is easy to think we understand something if it makes sense, but research on decision making shows that this can easily lead to faulty conclusions because our memories fail us. We tend to notice certain things and ignore others, and the specific manner in which information is framed can affect the choices we make. Therefore, it is important to rule out alternative explanations one by one rather than to assume we know about human behaviour just because we are humans! Go ahead and take the following quiz and see how many of the 10 questions you get right. If you miss a few, you will see that OB isn’t just common sense. If you get them all right, you are way ahead of the game!

Exercise – Putting Common Sense to the Test

Please answer the following 10 questions by noting whether you believe the sentence is true or false.

- Brainstorming in a group is more effective than brainstorming alone. _____

- The first 5 minutes of a negotiation are just a warm-up to the actual negotiation and don’t matter much. _____

The best way to help someone reach their goals is to tell them to do their best. _____ - If you pay someone to do a task they routinely enjoy, they’ll do it even more often in the future. _____

- Pay is a major determinant of how hard someone will work. _____

- If a person fails the first time, they try harder the next time. _____

- People perform better if goals are easier. _____

- Most people within organizations make effective decisions. _____

- Positive people are more likely to withdraw from their jobs when they are dissatisfied. _____

- Teams with one smart person outperform teams in which everyone is average in intelligence. ______

You may check your answers with your instructor.

Key Takeaways

- This book is about people at work.

- Organizations come in many shapes and sizes.

- Organizational behaviour is the systematic study and application of knowledge about how individuals and groups act within the organizations where they work.

- OB matters for your career, and successful companies tend to employ effective OB practices.

- The OB Toolboxes throughout this book are useful in increasing your OB skills now and in the future.

Exercises

- Which type of organizations did you have the most experience with? How did that affect your understanding of the issues in this chapter?

- Which skills do you think are the most important ones for being an effective employee?

- What are the three key levels of analysis for OB?

- Have you ever used journaling before? If so, were your experiences positive? Do you think you will use journaling as a tool in the future?

- How do you plan on using the OB Toolboxes in this book? Creating a plan now can help to make you more effective throughout the term.

- Kirkpatrick, D. (1998). The second coming of Apple. Fortune, 138, 90. ↵

- Parloff, R. (2008, January 22). Why the SEC is probing Steve Jobs. Money. Retrieved January 28, 2009, from http://money.cnn.com/2009/01/22/technology/stevejobs_disclosure.fortune/?postversion=2009012216. ↵

- Retrieved June 4, 2008, from http://www.litera.co.uk/t/NDk1MDA/. ↵

- Randstad. (2022, February 7). 5 reasons employees are leaving your organization [blog]. https://www.randstad.ca/employers/workplace-insights/talent-management/why-canadian-employees-are-changing-jobs ↵

- Gibson, E. (2008, March). Meg Whitman’s 10th anniversary as CEO of eBay. Fast Company, 25. ↵

- Section adapted from 1.1 The nature of work in OpenStax Organizational Behaviour shared under a CC BY license. ↵

- ibid. ↵

- S. Freud, Lecture XXXIII, New Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis (New York: Norton, 1933), p. 34. ↵

- NACE 2007 Job Outlook Survey. Retrieved July 26, 2008, from the National Association of Colleges and Employers (NACE) Web site: http://www.naceweb.org/press/quick.htm#qualities. ↵

- Huselid, M. A. (1995). The impact of human resource management practices on turnover, productivity, and corporate financial performance. Academy of Management Journal, 38, 635-672. ↵

- Pfeffer, J. (1998). The human equation: Building profits by putting people first. Boston: Harvard Business School Press. ↵

- Pfeffer & Veiga, 1999 ↵

- Welbourne, T., & Andrews, A. (1996). Predicting performance of Initial Public Offering firms: Should HRM be in the equation? Academy of Management Journal, 39, 910–911. ↵

- Pfeffer, J., & Veiga, J. F. (1999). Putting people first for organizational success. Academy of Management Executive, 13, 37–48. ↵

- Elmer-DeWitt, P. (2008, May 2). Top-paid CEOs: Steve Jobs drops from no. 1 to no. 120. Fortune. Retrieved July 26, 2008, from CNNMoney.com: http://apple20.blogs.fortune.cnn.com/2008/05/02/top-paid-ceos- steve-jobs-drops-from-no-1-to-no-120/. ↵

- Aguirre, D. M., Howell, L. W., Kletter, D. B., & Neilson, G. L. (2005). A global check-up: Diagnosing the health of today’s organizations (online report). Retrieved July 25, 2008, from the Booz & Company Web site: http://www.orgdna.com/downloads/GlobalCheckUp-OrgHealthNov2005.pdf. ↵

- Michaels, E., Handfield-Jones, H., & Axelrod, B. (2001). The war for talent. Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing. ↵

- Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, http://www.bls.gov. ↵

- Peters, T. (1997). The brand called you. Fast Company. Retrieved July 1, 2008, from http://www.fastcompany.com/magazine/10/brandyou.html.; Peters, T. (2004). Brand you survival kit. Fast Company. Retrieved July 1, 2008, from http://www.fastcompany.com/magazine/83/playbook.html. ↵

- Source: Adapted from ideas in Peters, T. (2007). Brand you survival kit. Fast Company. Retrieved July 1, 2008, from http://www.fastcompany.com/magazine/83/playbook.html. ↵

- Sources: Created based on ideas and information in Bromley, K. (1993). Journaling: Engagements in reading, writing, and thinking. New York: Scholastic; Caruso, D., & Salovey, P. (2004). The emotionally intelligent manager: How to develop and use the four key emotional skills of leadership. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; Scott, E. (2008). The benefits of journaling for stress management. Retrieved January 27, 2008, from About.com: http://stress.about.com/od/generaltechniques/p/profilejournal.htm. ↵