Chapter 7: Competing in International Markets

Advantages and Disadvantages of Competing in International Markets

Learning Objectives

- Understand the potential benefits of competing in international markets.

- Understand the risks faced when competing in international markets.

As Kia’s experience illustrates, fueled by globalization, international business has become a huge segment of the world’s overall economic activity. Amazingly, current projections suggest that, within a few years, the total dollar value of trade across national borders will be greater than the total dollar value of trade within all of the world’s countries combined. One driver of the rapid growth of international business over the past two decades has been the opening up of large economies such as China and Russia, which had been mostly closed off to outside investors and producers.

The United States, as a single country, has the world’s largest economy. Collectively, the European Union (EU) has a higher GDP than the United States, but of course it is composed of a group of nations. As an illustration of the power of the American economy, consider that, as of early 2011, the economy of just one state—California—if it were a country, would be ranked eighth largest in the world, between the UK and Russia. The U.S. capacity for production of manufactured and agricultural goods is far greater than can be consumed in America alone or NAFTA (North American Free Trade Agreement; includes Canada, Mexico, and the United States). As a result, the overall size of the U.S. economy has led American commerce to be very much intertwined with international markets.

As primarily a trading nation, Canada has also benefited from the rapid growth in international trade and globalization. Given our immense shared border with the United States, it is not surprising that Canada and the U.S. are each others’ largest trading partner, and the world’s largest trading partnership. In fact, it is fair to say that every Canadian business is affected by international markets to some degree, although services are typically affected to a lesser extent. Tiny businesses such as individual convenience stores and clothing boutiques sell products that are largely imported from abroad. Many Canadian manufacturing firms would be hard pressed to produce for only the Canadian market, as the volumes of potential sales would not allow them to achieve economies of scale. Many large corporations, on both sides of the border (e.g., General Motors (Canada), Coca-Cola, Blackberry, and Microsoft) conduct much of their business internationally (Wikipedia, 2014).

The Economist, a well-respected international magazine, has predicted that the economy of China, just 20 years ago a closed economic backwater, will be larger than that of the United States by 2019, based on real GDP growth, inflation, and the appreciation of the value of the yuan, China’s currency (S.C. & D.H., 2014). Economics suggests that the core reason for this remarkable growth has been the gradual opening of China’s border to trade. Their initially low salary scale, unlimited labor force, and few manufacturing restrictions have made China a major manufacturing and trade nation. More recently an emerging middle class has begun to fuel national consumption, further increasing the economic wealth of the nation (Wikipedia, 2014).

Access to New Customers

Perhaps the most obvious reason to compete in international markets is gaining access to new customers. Although the United States currently has the largest economy in the world, it accounts for less than 5 percent of the world’s population. Canada ranks at 0.5 percent of the world’s population. Selling goods and services to the other 95 percent of people on the planet can be very appealing, especially for companies whose home market is saturated (Figure 7.3 “Why Compete in New Markets?”).

Few companies have a stronger “American” identity than McDonald’s. Yet McDonald’s is increasingly reliant on sales outside the United States. In 2006, the United States accounted for 34 percent of McDonald’s revenue, while Europe accounted for 32 percent, and Asia, the Middle East, and Africa accounted for 14 percent. By 2012 Europe was McDonald’s biggest source of revenue (39 percent), the U.S. share had fallen to 32 percent, and the collective contribution of Asia, the Middle East, and Africa had jumped to 23 percent. With less than one-third of its sales being generated in its home country, McDonald’s is truly a global powerhouse (University of Oregon Investment Group, 2013).

China and India are increasingly attractive markets to U.S. firms. The two most populous nations in the world, both have growing middle classes, defined loosely as people financially able to purchase goods and services that are not merely necessities of life. With their immense population numbers, if only 1 percent of Chinese became middle class over the next three years, that would be 16 million potential new consumers! This trend has created tremendous opportunities for some firms. In 2013, for example, GM sold more vehicles in China than it sold in the United States (3.2 million vs. 2.8 million) (Szczesny, 2014).

GM is not alone in moving into China. Ford Motor Company sold a total of 935,813 vehicles in China in 2013, setting another annual record. Toyota and its two joint-venture partners recorded sales of 917,500 units, a 9.2 percent increase, while Honda’s China volume jumped 26 percent to 756,882. Meanwhile, sales for Japanese brands in China continued to suffer early last year amid boycotts and violent protests that occurred after Japan renewed its claims on the disputed Senkakus islands in the East China Sea, noted for their potential offshore oil and gas reserves (Miller, 2014).

Lowering Costs

Offshoring has become a popular yet controversial means of trying to reduce costs. Offshoring involves relocating a business activity to another country. Many Canadian and U.S. companies have closed down operations at home in favor of creating new operations in countries such as China and India that offer cheaper labor. While offshoring can reduce a firm’s costs of doing business, the job losses in the firm’s home country can devastate local communities, leading to negative publicity.

Many firms that compete in international markets hope to gain cost advantages. When a firm increases sales volume by entering a new country, for example, it may generate economies of scale that lower its overall and average production costs. Economics of scale may be linked to greater production from existing facilities (sharing fixed costs across larger sales) and other shared costs such as research and development (R&D) and marketing. It also has the potential to diversify risks. As well, going international has implications for dealing with suppliers. The growth that overseas expansion creates leads many businesses to purchase supplies in greater amounts and from suppliers in multiple countries, reducing risk. This can provide a firm with stronger leverage when negotiating prices with its existing suppliers.

For example, major companies continue to outsource much of their IT work to specialists, a move that in many cases makes good business sense. The majority of employers (six out of ten) said cost savings was the main benefit of outsourcing, which they estimated at 35 percent on average, according to an IDC survey called Outsourcing Monitor in June 2012. Competitive advantage and access to specialized skills also ranked high on the list of benefits, the survey found. Most IT work is still performed in Canada, IDC says, but a growing share of the market is going to companies outside the country. Offshore firms account for $3 billion of the Canadian outsourced IT market. And their share is rising 20 percent a year. They’re handling everything from check processing to large databases, IDC says.

However, a growing number of U.S. companies are finding that offshoring is not providing the benefits they had expected. This has led to a new phenomenon known as reshoring, whereby jobs that had been sent overseas are returning home. In some cases, the quality provided by workers overseas is not good enough. Carbonite, a seller of computer backup services, found that its call centre in Boston was providing much stronger customer satisfaction than its call centre in India. The Boston operation’s higher rating was attained even though it handled the more challenging customer complaints. As a result, Carbonite returned 250 call centre jobs to the United States in 2012.

After spending a couple of decades advising Western clients on how to “offshore” their production facilities to low-cost jurisdictions in Asia, business consultancies say it might be time to bring some of that work home. The combination of rising wages in China, elevated shipping costs, and a rethinking of supply chains is making North America the hot “new” global manufacturing hub. Boston Consulting Group predicts the combination of production returning from China and increased exports will create between 600,000 and one million jobs in the United States over the next decade (Flavelle, 2013).

This wave of reshoring has yet to touch Canada’s shores, reflecting the country’s status as a relatively expensive place to assemble gadgets, parts, and machinery. That raises a policy question for officials in Ottawa and the provincial capitals that they haven’t had to consider for a long time: How far are they willing to go to win factory work? (Carmichael, 2012; Ovsey, 2013)

Earlier this year, research company Alix Partners released a report that showed the United States had reached cost parity with Mexico as a preferred “nearshoring” location, and that it would reach similar parity with China by 2015. In lay terms, that means it costs American companies no more to keep their production on home turf than it does to offshore it to traditionally low-cost locales in Asia.

In other cases, the expected cost savings of offshore production have not materialized. In the United States, NCR had been making ATMs and self-service checkout systems in China, Hungary, and Brazil. These machines can weigh more than a ton, and NCR found that shipping them from overseas plants back to the United States was extremely expensive. NCR hired 500 workers to start making the ATMs and checkout systems at a plant in Columbus, Georgia. NCR’s plans call for 370 more jobs to be added at the plant by 2014. Similarly, General Electric announced plans to hire approximately 1,300 workers in Louisville, Kentucky, starting in the fall of 2011. These workers make water heaters and refrigerators that had been produced overseas (Isidore, 2011). Snapper, a high-quality lawn mower manufacturer located in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, concluded that the long transportation times from China did not allow them to respond quickly enough to emerging opportunities, often weather related, and so they kept production facilities in the United States.

Diversification of Business Risk

A familiar cliché warns “don’t put all of your eggs in one basket.” Applied to business, this cliché suggests that there is a certain risk for firms operating in only one country. Business risk refers to the potential that an operation might fail. If a firm is completely dependent on one country, from either a supply or market perspective, negative economic, political, or natural disasters in that country can create significant difficulty, as the Japanese earthquake of 2011 proved. Just like spreading one’s eggs into multiple baskets reduces the chances that all eggs will be broken, business risk is reduced when a firm diversifies across multiple countries.

Consider, for example, natural disasters such as the earthquakes and tsunami that hit Japan in 2011. If Japanese automakers such as Toyota, Nissan, and Honda sold cars only in their home country, the financial consequences could have been grave. Because these firms operate in many countries, however, they were protected from being ruined by events in Japan. In other words, these firms diversified their business risk by not being overly dependent on their Japanese operations.

American cigarette companies such as Philip Morris and R. J. Reynolds are challenged by trends within Canada, the United States, and Europe. Tobacco use in these areas is declining as laws are passed restricting smoking in public areas and restaurants, high taxation on smoking continues, and society’s views of smoking change. In response, cigarette makers are attempting to increase their operations within countries where smoking remains popular so they can remain profitable over time. They have also introduced e-cigerettes as a separate business line to retain customers and profits.

In 2006, for example, Philip Morris spent $5.2 billion to purchase a controlling interest in Indonesian cigarette maker Sampoerna. This was the biggest acquisition ever in Indonesia by a foreign company. Tapping into Indonesia’s population of approximately 230 million people was attractive to Philip Morris in part because nearly two-thirds of men are smokers, and smoking among women is on the rise. As of 2007, Indonesia was the fifth-largest tobacco market in the world, trailing only China, the United States, Russia, and Japan. To appeal to local preferences for cigarettes flavored with cloves, Philip Morris introduced a variety of its signature Marlboro brand called Marlboro Mix 9 that includes cloves in its formulation (T2M, 2007). Although unit sales of Philip Morris products overseas dropped 5 percent from 2012 to 2013, profits rose by concentrating on its profitable, high-profile Marlboro brand.

Since 2009, Philip Morris International and Swedish Match AB have operated a joint venture company that has commercialized smokeless tobacco products outside of Scandinavia and the United States. Through this joint venture company, PMI sells smokeless tobacco products, including Swedish snus (Philip Morris International, 2014).

Political Risk

Although competing in international markets offers important potential benefits, such as access to new customers, the opportunity to lower costs, and the diversification of business risk, going overseas also poses daunting challenges. Political risk refers to the potential for government upheaval or interference with business to harm an operation within a country (Figure 7.8 “Entering New Markets: Worth the Risk?”).

The relative stability of Canadian, U.S., and European governments leaves citizens unfamiliar with the significant political disruption that can occur with a military takeover (Thailand), military or terrorist insurrection (Egypt), or outright war (Iraq). One example of larger political change is the “Arab Spring,” a term used to refer to a series of uprisings in 2011 in countries such as Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, Bahrain, Syria, and Yemen, as their populations sought to overthrow corrupt governments.

Similarly, in 2013 and 2014, military conflict between Russia and Ukraine sent international oil prices upward on fears of further instability in oil-rich countries. Unstable governments associated with such demonstrations and uprisings make it difficult for firms to plan for the future. Over time, a government could become increasingly hostile to foreign businesses by imposing new taxes and new regulations. In extreme cases, a firm’s assets in a country may be seized by the national government. This process is called nationalization. In recent years, for example, Venezuela has nationalized foreign-controlled operations in the oil, cement, steel, and glass industries.

Countries with the highest levels of political risk tend to be those such as Somalia, Sudan, and Afghanistan whose governments are so unstable that few foreign companies are willing to go there. High levels of political risk are also present, however, in several of the world’s important emerging economies, including India, the Philippines, Russia, and Indonesia. This creates a dilemma for firms in that these risky settings also offer enormous growth opportunities. Firms can choose to concentrate their efforts in countries such as Canada, Australia, South Korea, and Japan that have very low levels of political risk, but opportunities in such settings are often more modest (Kostigen, 2011).

Economic Risk

Economic risk refers to the potential for a country’s economic conditions and policies, property rights protections, and currency exchange rates to adversely affect a firm’s operations within a country. Executives who lead companies that do business in many different countries have to take stock of these various dimensions and try to anticipate how the dimensions will affect their companies. Because economies are unpredictable, economic risk presents executives with tremendous challenges.

Hyundai and Kia are flagship companies of Hyundai Motor Group, the world’s fifth-largest automotive conglomerate. Car sales by Hyundai Motor Co. backtracked in Europe in 2013 amid weak overall market conditions, while its smaller sibling Kia Motors Corp. managed to increase its presence on the continent (The Korean Herald, 2014).

Consider, for example, Kia’s operations in Europe. Kia has achieved sales volume growth in Europe every year since 2008, increasing market share from 1.7 percent to 2.7 percent in 2013. This success, often going against the overall market downturn, is a tribute to Kia’s design, product range, quality, and warranty. As Kia’s executives planned for the future, they needed to wonder how economic conditions would influence Kia’s future performance in Europe. If inflation and interest rates were to increase in a particular country, this would make it more difficult for consumers to purchase new Kias. If currency exchange rates were to change such that the euro became weaker relative to the South Korean won, this would make a Kia more expensive for European buyers (Kia.com, 2014).

Cultural Risk

Cultural risk refers to the potential for a company’s operations in a country to struggle because of differences in language, customs, norms, and customer preferences (Figure 7.11 “Cultural Risk: When in Rome”). The history of business is full of colorful examples of cultural differences undermining companies. For example, a laundry detergent company was surprised by its poor sales in the Middle East. Executives believed that their product was being skillfully promoted using print advertisements that showed dirty clothing on the left, a box of detergent in the middle, and clean clothing on the right. A simple and effective message, right? Not exactly. Unlike English and other Western languages, the languages used in the Middle East, such as Hebrew and Arabic, involve reading from right to left. To consumers, the implication of the detergent ads was that the product could be used to take clean clothes and make them dirty. Not surprisingly, few boxes of the detergent were sold before this cultural blunder was discovered.

A refrigerator manufacturer experienced poor sales in the Middle East because of another cultural difference. The firm used a photo of an open refrigerator in its prints ads to demonstrate the large amount of storage offered by the appliance. Unfortunately, the photo prominently featured pork, a type of meat that is not eaten by the Jews and Muslims who make up most of the area’s population (Ricks, 1993). To get a sense of consumers’ reactions, imagine if you saw a refrigerator ad that showed meat from a horse or a dog. You would likely be disgusted. In some parts of world, however, horse and dog meat are accepted parts of diets. Firms must take cultural differences such as these into account when competing in international markets.

Cultural differences can cause problems even when the cultures involved are very similar and share the same language. During the 2000 Summer Olympics held in Sydney, Australia, clothing manufacturer Roots was the official outfitter for members of the Canadian Olympic and Paralympic teams. The Roots brand was emblazoned on the Olympians’ distinctive uniforms, and the Roots clothing was also sold on-site at the games. The fact that “root” is an Aussie slang for “sexual intercourse” and often replaces the F-bomb in sentences may have somewhat helped its popularity Down Under. Who doesn’t want a bag that says “Roots” on it?

RecycleBank is an American firm that specializes in creating programs that reward people for recycling, similar to airlines’ frequent-flyer programs. In 2009, RecycleBank expanded its operations into the UK. Executives at RecycleBank became offended when the British press referred to RecycleBank’s rewards program as a “scheme.” Their concern was unwarranted, however. The word scheme implies sneakiness when used in the United States, but a scheme simply means a service in the UK (Maltby, 2010). Differences in the meaning of English words between the United States and the UK are also vexing to American men named Randy, who wonder why Brits giggle at the mention of their name (Figure 7.13 “Watch Your Language”).

Key Takeaways

- Competing in international markets involves important opportunities and daunting threats. The opportunities include access to new customers, lowering costs, and diversification of business risk. The threats include political risk, economic risk, and cultural risk.

Exercises

- Is offshoring ethical or unethical? Why?

- Do you expect reshoring to become more popular in the years ahead? Why or why not?

- Have you ever seen an advertisement that was culturally offensive? Why do you think that companies are sometimes slow to realize that their ads will offend people?

References

Carmichael, K. (2012, June 20). Canada’s ‘Reshoring’ Opportunity. The Globe and Mail. Retrieved from http://www.theglobeandmail.com/report-on-business/economy/canada-competes/canadas-reshoring-opportunity/article4230748/

Chesto, J. (2011, May 24). Boston company gives up on offshoring call centre jobs to India, moves them to Maine instead. Mass.Market. Retrieved from

http://blogs.wickedlocal.com/massmarkets/2011/05/24/boston-company-gives-up-on-offshoring-call-center-jobs-to-india-moves-them-to-maine-instead/#ixzz3BnH3owUl

Flavelle, D. (2013, February 4). iGate: Offshore firms capture more IT work, study shows. The Star. Retrieved from http://www.thestar.com/business/2013/04/10/igate_offshore_firms_capture_more_it_work_study_shows.html

Isidore, C. (2010. July 2). GM’s Chinese sales top US. CNNMoney. Retrieved from http://money.cnn.com/2010/07/02/news/companies/gm_china/index.htm

Isidore, C. (2011, June 17). Made in USA: Overseas jobs come home. CNNMoney. Retrieved from http://money.cnn.com/2011/06/17/news/economy/made_in_usa/index.htm

Kia.com. (2014, April 7). Best-ever monthly and quarterly retail sales for Kia Europe. Retrieved from http://press.kia.com/eu/press/corporate/14_04_07_29%20-%20record%20q1%20european%20sales/

Kia Corporation. (2009, June 5). Kia sales climb strongly in 10 countries in May. Retrieved from http://www.kia-press.com/press/corporate/20090605-kia%20sales%20 climb%20strongly%20in%2010%20countries.aspx

Kostigen, T. (2011, February 25). Beware: The world’s riskiest countries. Market Watch. Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from http://www.marketwatch.com/story/beware-the -worlds-riskiest-countries-2011-02-25

Maltby, E. (2010, January 19). Expanding abroad? Avoid cultural gaffes. Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from http://online.wsj.com/article/SB100014240527487036 57604575005511903147960.html

Miller, D. (2014, June 11). Ford Motor Company Could Shake Up China’s Vehicle Sales Rankings Soon, The Motley Fool. Retrieved from http://www.fool.com/investing/general/2014/06/11/ford-motor-company-remains-on-pace-to-shake-up-chi.aspx

Ovsey, D. (2013, November 25). How U.S. Reshoring Will Force Canadian Manufacturers to Innovate – And Change the Very Nature of the Sector. National Post. Retrieved from http://business.financialpost.com/2013/11/25/how-u-s-reshoring-will-force-canadian-manufacturers-to-innovate-and-change-the-very-nature-of-the-sector/?__lsa=dba7-a5c6

Philip Morris International. (2014). Our Brands. Retrieved from http://www.pmi.com/eng/our_products/pages/our_brands.aspx

Ricks, D. A. (1993). Blunders in international business. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

S.C. & D.H. (2014, May 2). Chinese and American GDP Forecasts, Catching the Eagle. Retrieved from http://www.economist.com/blogs/graphicdetail/2014/05/chinese-and-american-gdp-forecasts

Szczesny, J. (2014). GM sells more cars in China than US again. MSN Autos. Retrieved from http://editorial.autos.msn.com/gm-sells-more-cars-in-china-than-us-again

T2M. (2007, July 3). Clove-flavored Marlboro now in Indonesia. Retrieved from http://www.the-two-malcontents.com/2007/07/clove-flavored-marlboro- now-in-indonesia

The Economist. (2011, January). Stateside substitutes. Retrieved from http://www.economist.com/blogs/dailychart/2011/01/comparing_us_states_ countries

The Korean Herald. (2014, January 17). Hyundai’s European sales dip, Kia market share edges up in 2013. Retrieved from http://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20140117000201

University of Oregon Investment Group. (2013, December 6). Consumer Goods. McDonald’s. Retrieved from http://uoinvestmentgroup.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/MCD-Report-with-formating-that-displays-2018.pdf

Wikipedia Organization. (2014). Canada-United States relations. Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Canada%E2%80%93United_States_relations

Wikipedia Organization. (2014). Comparison between U.S. states and countries by GDP (nominal). Retrieved from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Comparison_between_U.S._states_and_countries_by_GDP_(nominal)

Image description

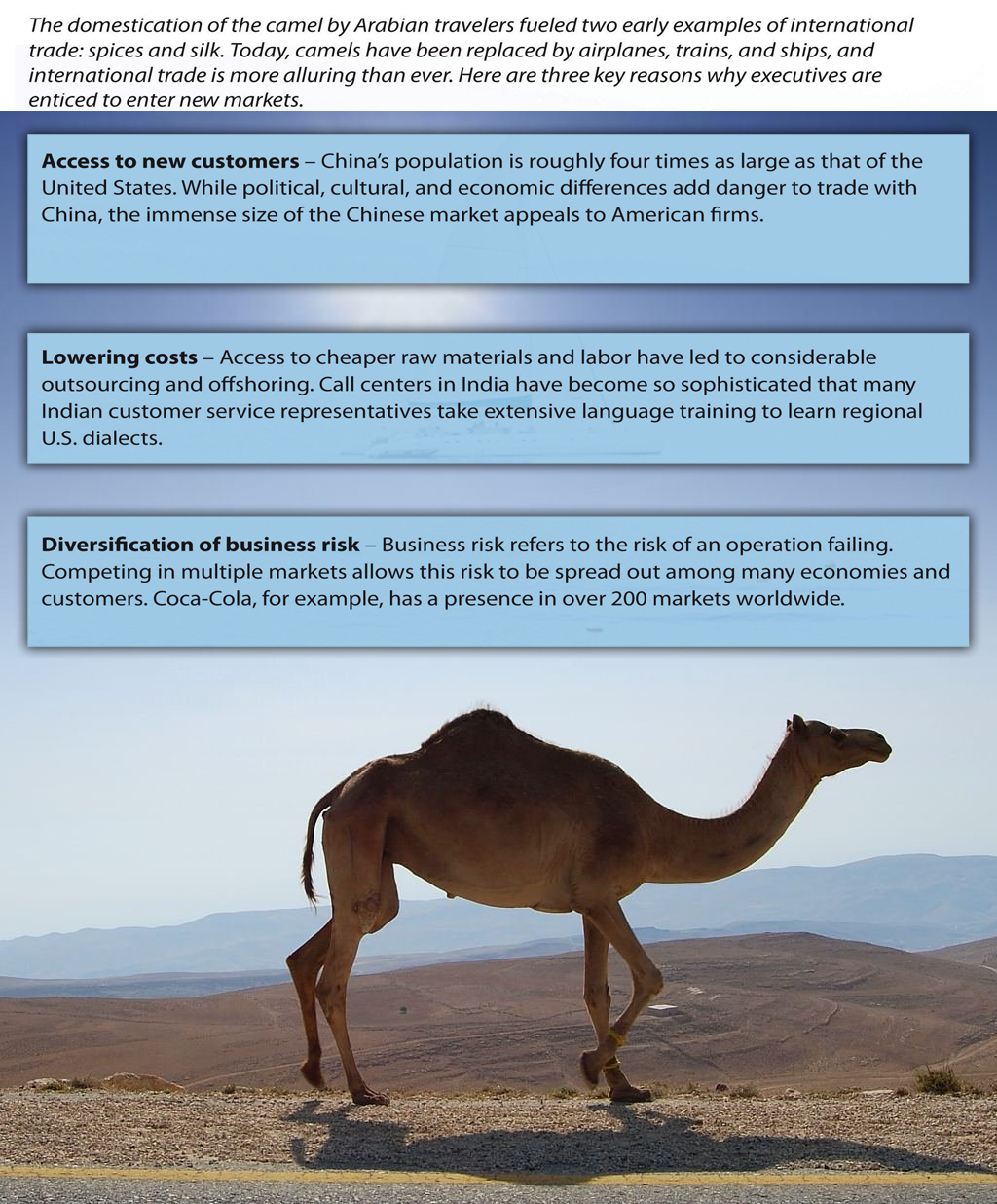

Figure 7.3 image description: Why Compete in New Market

The domestication of the camel by Arabian travelers fueled two early examples of international trade: spices and silk. Today, camels have been replaced by airplanes, trains, and ships, and international trade is more alluring than ever. Here are three key reasons why executives are enticed to enter new markets.

- Access to new customers — China’s population is roughly four times as large as that of the United States. While political, cultural, and economic differences add danger to trade with China, the immense size of the Chinese market appeals to American firms.

- Lowering costs — Access to cheaper raw materials and labor have led to considerable outsourcing and offshoring. Call centers in India have become so sophisticated that many Indian customer service representatives take extensive language training to learn regional U.S. dialects.

- Diversification of business risk — Business risk refers to the risk of an operation failing. Competing in multiple markets allows this risk to be spread out among many economies and customers. Coca-Cola, for example, has a presence in over 200 markets worldwide.

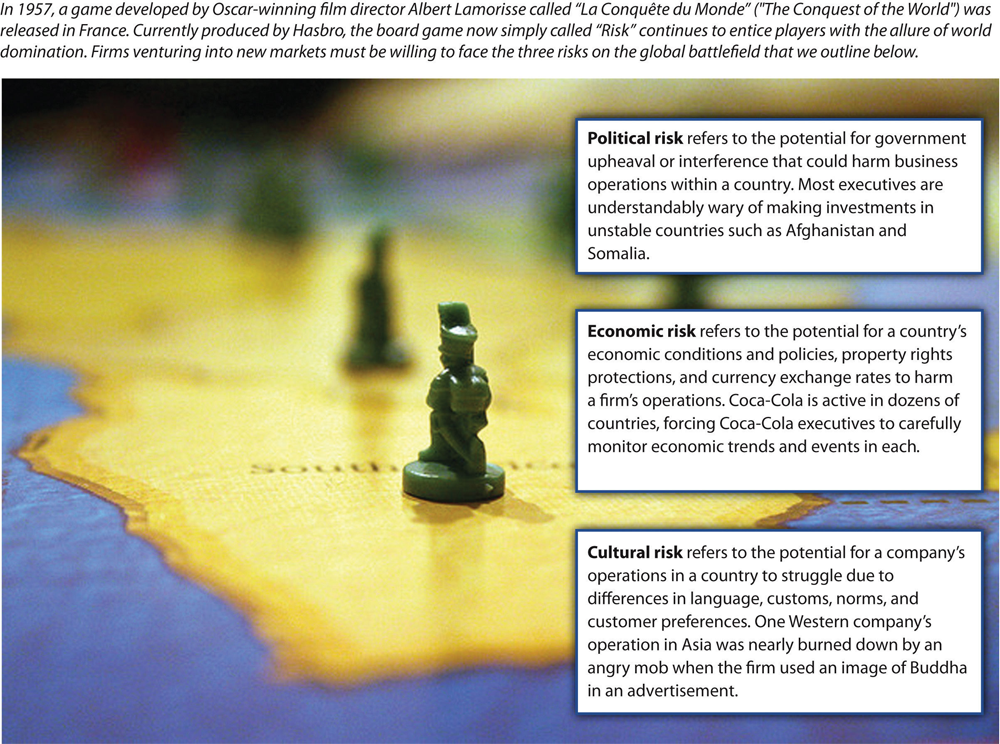

Figure 7.8 image description: Entering New Markets: Worth the Risk?

In 1957, a game developed by Oscar-winning film director Albert Lamorisse called “La Conquête du Monde” (‘The Conquest of the World”) was released in France. Currently produced by Hasbro, the board game now simply called “Risk” continues to entice players with the allure of world domination. Firms venturing into new markets must be willing to face the three risks on the global battlefield that we outline below.

- Political risk refers to the potential for government upheaval or interference that could harm business operations within a country. Most executives are understandably wary of making investments in unstable countries such as Afghanistan and Somalia.

- Economic risk refers to the potential for a country’s economic conditions and policies, property rights protections, and currency exchange rates to harm a firm’s operations. Coca-Cola is active in dozens of countries, forcing Coca-Cola executives to carefully monitor economic trends and events in each.

- Cultural risk refers to the potential for a company’s operations in a country to struggle due to differences in language, customs, norms, and customer preferences. One Western company’s operation in Asia was nearly burned down by an angry mob when the firm used an image Of Buddha in an advertisement.

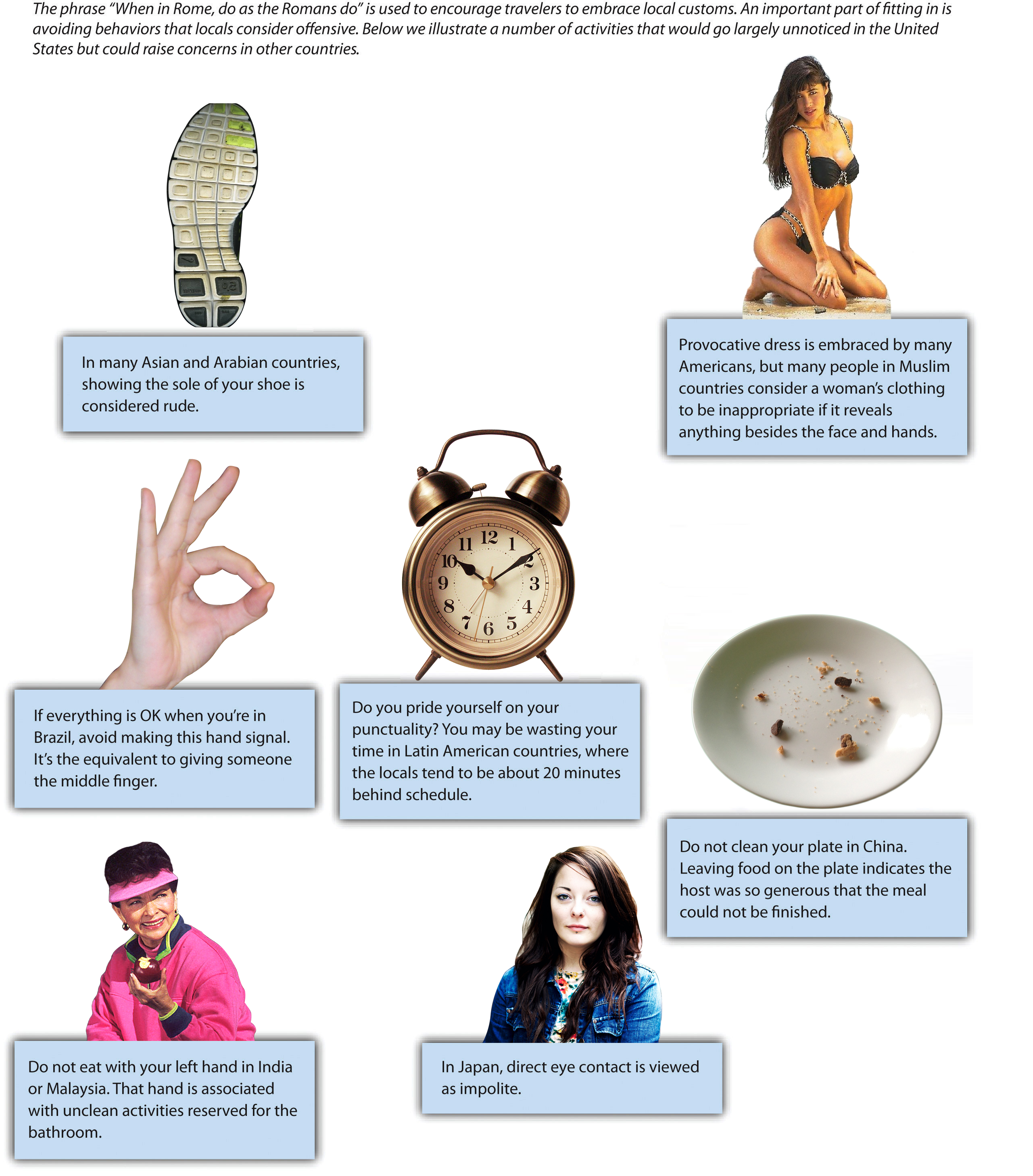

Figure 7.11 image description: Cultural Risk: When in Rome

The phrase “When in Rome, do as the Romans do” is used to encourage travelers to embrace local customs. An important part of fitting in is avoiding behaviour that locals consider offensive. Below we illustrate a number of activities that would go largely unnoticed in the United States but could raise concerns in other countries.

- In many Asian and Arabic countries, showing the sole of your shoe is considered rude.

- Provocative dress is embraced by many Americans, but many people in Muslim countries consider a woman’s clothing to be inappropriate if it reveals anything besides the face and hands.

- If everything is OK when your are in Brazil, avoid using the OK hand signal. It’s the equivalent to giving someone the middle finger.

- Do you pride yourself on your punctuality? You may be wasting your time in Latin American countries, where the locals tend to be about 20 minutes behind schedule.

- Do not clean you plate in China. Leaving food on the plate indicates the host was so generous that the meal could not be finished.

- Do not eat with your left hand in India or Malaysia. That hand is associated with unclean activities reserved for the bathroom.

- In Japan, direct eye contact is viewed as impolite.

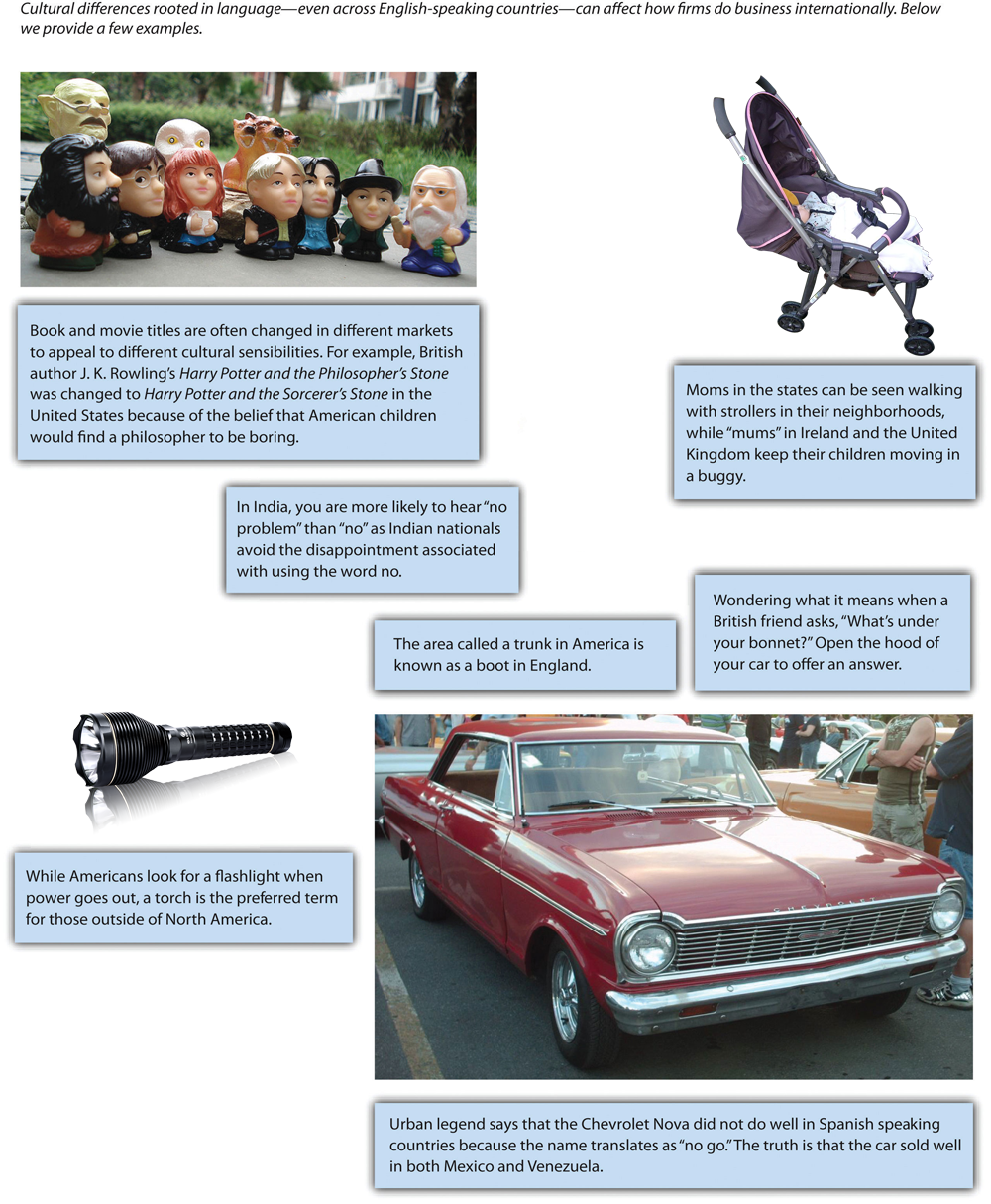

Figure 7.13 image description: Watch Your Language

Cultural differences rooted in language – even across English-speaking countries – can affect how firms do business internationally. Below we provide a few examples.

- Book and movie titles are often changed in different markets to appeal to different cultural sensibilities. For example, British author J. K. Rowling’s Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone was changed to Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone in the United States because of the belief that American children would find a philosopher to be boring.

- In India, you are more likely to hear “no problem” than Ono” as Indian nationals avoid the disappointment associated with using the word no.

- The area of a car called as trunk in America is known as boot in England

- Moms in the States can be seen walking with strollers in their neighborhoods, while “mums” in Ireland and the United Kingdom keep their children moving in a buggy.

- Wondering what it means when a British friend asks, “What’s under your bonnet?” Open the hood of your car to Offer an answer.

- While Americans look for a flashlight when power goes out, a torch is the preferred term for those outside of North America,

- Urban legend says the Chevrolet Nova did not do well in Spanish speaking countries because the name translates as “no go.” The truth is that the car sold well in both Mexico and Venezuela.

The relocation of a business activity to another country.

The relocation of jobs that had been sent overseas back to a firm’s home country.

The potential that a business operation might fail.

The potential for government upheaval or interference with business to harm an operation within a country.

The seizure of privately owned business operations by a national government.

The potential for a country’s economic conditions and policies, property rights protections, and currency exchange rates to harm a firm's operations.

The potential for a company’s operations in a country to struggle because of differences in language, customs, norms, and customer preferences.