3 Creating Safe Indoor Environments

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

- Connect classroom design to safety and injury prevention.

- Discuss ways to handle unsafe behaviour by understanding the function of behaviours.

- Describe how teachers can ensure the toys and materials they offer children do not present injury risks and are nontoxic.

- Explain ways adults can support safe and developmentally appropriate use of technology.

- Lists ways to protect children from choking, poisoning, burns, drowning, and falls.

- Identify how to implement safe sleep practices to protect against Sudden Infant Death Syndrome.

Introduction

Designing an effective and engaging classroom environment takes careful thought and planning, but it’s important. A well-organized classroom that is interesting, orderly, and attractive contributes to children’s participation and engagement with the learning materials and activities. This engagement, in turn, contributes to children’s learning.

Let’s look at it from a child’s perspective. We want children to feel safe and comfortable in the classroom. We want them to be interested in the learning activities and to take full advantage of being at school and take full advantage of the activities you’ve planned and the materials you’ve selected. It can be helpful to get down at a child’s level and take a look at the classroom. Does it feel welcoming and inviting? Is there enough room to move, make choices, and stay involved with a toy or activity or project? And does the room help the child know what to do and what’s expected?

Designing an Effective and Safe Classroom Environment

There are all sorts of classrooms. They differ by size and shape, amount of light and wall space, placement of sinks and counters, and amount of storage. Figuring out how to design the physical space and to maximize children’s interactions within the space will take some time. Make a floor plan. Move things around. Take a look at other classrooms and see what works.

Here are a few things to think about when designing your space and making it as workable as possible. Think about the number of interest areas or centers that you want or need for the group of children. Arrange the space so that noisy areas are separated from quiet areas. Locate centers next to needed storage or equipment. Use furniture or other items to provide boundaries. But, make sure that the adults can see all of the areas of the room. [2]

Factors to Consider

Space and boundaries:

- Are the centers clearly defined with furniture, rugs, or shelves?

- Is there enough space for all children to easily move about the room?

- In each defined area, is there adequate space for the number of children using it?

Proximity and distance:

- Are the quiet and noisy areas in proximity or separated?

- Are centers located near things that children need to complete projects (art center near sink, puzzle or game shelves within reach of tables, etc.)?

- Are teachers able to view children in all centers?

Home and culture:

- What home-like features are included in the classroom?

- How is(are) the culture(s) of the local community reflected in the classroom?

Flexibility and permanence:

- How does the space accommodate gross motor activity?

- What aspects of the physical space cannot be changed (cost or structural issues) and are challenging to overcome (e.g., limited access to natural light, cumbersome cubbies, etc.)?

Engagement and challenging behaviours:

- Are there areas of the classroom where challenging behaviours are more likely to occur?

- Are there areas where typically children are positively engaged in classroom activities?

Traffic patterns:

- Can children move easily from space to space?

- Is running and wandering discouraged?

Material selection:

- Are materials chosen to support development and learning?

- Are they culturally relevant and meaningful to the children?

- Is there is a sufficient variety and quantity (without overwhelming children)? [3]

Pause to Reflect

Tips for Environmental Design

- Traffic patterns need to discourage running.

Figure 3.2 – This large space was transformed with this rug and arrangement of materials and furniture. - Use furniture, rugs, and similar items to define boundaries.

- Ensure that teachers can see what is happening in all areas of the classroom.

- Cultural and home-like features are present in the room.

- Use spaces with as much flexibility as possible.

- Quiet and noisy centers are spaced appropriately.

- Ensure interesting classroom content selection is balanced with appropriate stimulation versus overstimulation.

- Each center provides enough information about what to do there and how to play. [4]

Grouping of Children

Teachers want to be intentional about how they group children, whether it’s a decision made in the moment or as part of lesson planning. Match the size of the group with the purpose of the activity. Think about the children who will be in the group. Young children need opportunities to participate and learn with the whole group, small groups, and they will thrive with a bit of one-on-one time with an adult. [6]

Large groups are good for:

- Introducing concepts

- Building community

- Conducting routine activities

Small groups are good for:

- Maximizing back and forth interactions

- Peer modeling of skills

- Guiding instruction

One-on-one interactions are good for:

- Tasks requiring complex skills

- Instance when a child needs specific direction and assistance. [7]

Pause to Reflect

- How is considering group size related to safety?

- What might teachers need to observe for to determine if the group sizes are working well for the children?

Every early childhood environment is full of pros and cons; it is how educators work with the many characteristics of a classroom that can make a tremendous difference. Teachers can be surprised by the results when they:

- Assess the spaces for both limitations and strengths.

- Strategize how to optimize what they have to work with in their classrooms.

- Try a different arrangement, see what happens, and then modify based on what is working and what is not.

Sometimes a modification can be minor (raising or lowering a shelf, “stop” signs over unavailable areas, masking tape to better define a space, etc.). This highlights the “work-in-progress” nature of early childhood environments. As the needs of children change, the room may need minor changes or have to be rearranged completely to meet those needs. [8]

A Few More Considerations for Environmental Design

When designing classroom environments, there are some other considerations to keep in mind:

Rotations:

- Avoid grouping the same children together all the time, especially when pairing skilled with less skilled children.

- Consider limiting the number of children per center and creating a system for rotating children through favourite areas.

- Regularly rotate some of the toys and materials to generate a sense of newness.

- Instruction can be tailored within small groups to meet educational goals. For example, one group of children that is working on learning numbers can read a counting book; another group working on fine motor skills can do beading; still another group of children working on social skills can practice joining play.

- Emphasize cooperation by choosing toys and activities that require it (e.g., large appliance boxes, games that need two or more players, balls for throwing back and forth, etc.).

- Whenever possible keep the design elements simple (both for the teacher’s sake and because simple tends to be longer-lasting). Also, some aspects of designing can be done spontaneously and quickly (spur of the moment) and still be effective. [10]

Interpersonal Safety

Children can behave in ways that hurt themselves or others so teachers must prepared to handle unsafe behaviours in their duty to protect children from injury. An important way to think about behaviour is as a form of communication. Young children let us know their wants and needs through their behaviour long before they have or can use words in the heat of the moment. They give us cues to help us understand what they are trying to communicate.

Early childhood educators can help children by interpreting their cues and responding to meet their needs. The following example illustrates the importance of responding to the possible meaning behind behaviour:

Javon bites Blair because he wants the block she is playing with and we remove Javon from the situation. Not only are we not responding to his want or need, but we are taking him out of the context where he can learn to communicate his feelings in a way that doesn’t hurt others.

Forms and Functions of Behaviour

There are many reasons a child might use specific behaviours. This is why it is important for adults to carefully observe children, pay attention to their cues, get to know them, and know what part of the schedule gives them a hard time to better understand what they are trying to tell us through their behaviour.[11]

Each behaviour has a Form and a Function:

- Form = the behaviour the child is using to communicate.

- Function = the reason or purpose the child is using that behaviour.[12]

Forms of Communication

Crying , Cooing, Reaching for caregiver, Kicking their legs , Gaze aversion (looking away), Squealing, Biting, Tantrums, Pointing, Smiling, Pulling adult, Clapping, Words, Jumping.

Functions of Communication

Obtain an object, activity, person; Request help; Initiate social interaction; Request information; Seek sensory stimulation; Escape demands; Escape activity; Avoid a person; Escape sensory stimulation; Express emotion; Express pain or illness .

Examples of Possible Functions of Communication [14]

Toddler biting:

- I want the dinosaur Joseph is playing with.

- I’m teething.

- This is my space — I don’t want you in my space.

- I am really frustrated.

- You just told me “no” and I don’t like it.

- I want to play with you.

Preschooler hitting:

- I feel mad and don’t know how to express it.

- I don’t want to stop playing.

- I don’t want to share my favourite toy.

- I want to play by myself.

Culture

Form and function are also shaped by culture. Children are socialized to express their feelings in culturally acceptable ways. It is important to talk with families so you can look for acceptable ways that children express themselves in a culturally respectful way.

As you have probably already experienced—it is not always easy to figure out the meaning of a child’s behaviour. To add to the complexity of understanding the meaning of behaviour:

A single form of behaviour may serve more than one function. For example, a toddler might use biting (form) for different functions (“I want the toy you have.” “I want to play with you but don’t know how to let you know.” “I’m tired.” “I’m frustrated because you don’t understand what I am trying to tell you.” “I want some attention.”)

Several forms of behaviour may serve one function. For example, a child’s purpose (function) may be to build with their favourite blocks, but they use different forms of behaviour (biting, yelling, grabbing, running away with the blocks, sharing) based on how they feel that day, who is playing in the block area, or based on their cultural expectations.

The meaning of behaviour is shaped by culture, family, and the unique makeup and experiences of the individual child. For example, some cultures may express sadness by crying or by having a nonchalant facial expression. Some cultures may express happiness by laughing and being exuberant, while others may expect more restrained behaviours.

Some of these functions of communication become a concern for children’s safety (of the child communicating, the other children, and other people in the environment). Early childhood educators must take the time to understand a behaviour’s meaning so that they can help the child replace unsafe forms of communication with forms that don’t hurt others or harm the environment. Pausing to try to figure out the meaning behind a child’s behaviour—instead of just reacting to the behaviour—can change the way we see a child, the way we respond to a child, and the way we teach a child. Becoming a “behaviour has meaning” detective who is always on the lookout for the meaning of behaviour will help you keep children safe.[15] Take a look at the following example of an unsafe behaviour, what it might mean, and what an educator might do to support the child.

Emilia and Sarae

Teacher Emilia says about a child Sarae, “I have to watch her like a hawk or she’ll run down the hall or go out the gate, down the street, and I don’t know where.”

What This Might Mean

So, we could reframe this to: Sarae is an active child. She may naturally be a kinesthetic learner, who needs to move and shake, has extra energy.

What the Teacher Might Do

A teacher can give Sarae positive ways to exercise the way she loves to be. So, whether that’s during choice time, that there is an opportunity for her to dance, for example. Or, there’ s an obstacle course set up for her to maneuver through.

When they are outdoors, the teacher can create opportunities for structured play so that is running with an intention; such as part of a game with her peers. If it’s hard to get her back inside, give her a leadership role. Maybe she’s the one who has the bell that cues everybody that it’s time to line up. So now she’s going to make sure she finds her friends and is the one responsible for bringing the whole group together to go inside.

The Potential Result

Reframing the behaviour and provide positive outlets will not only keep Sarae safe, but it will also communicate to her that how she feels is okay and that she’s being supported, acknowledged, and encouraged. [11]

Taking a Closer Look at Behavior

You may also find it valuable to examine behaviour much the way you would injuries and traffic patterns. Gather data about unsafe behaviours:

- When are they happening? Are there specific times of day that children are finding it more challenging to behave/communicate in safe ways?

- Where are they happening? Are there hot spots for challenging behaviour? What in the environment might be the focus of the unsafe behaviour/communication?

- Why they are happening? What happened before the led up to the behaviour? What happened after?

- Who are the behaviours happening between? All children will have times where they communicate with unsafe behaviour, but some children may need more adult support in certain contexts (time of day, activity, groupings of children, etc.).

- Look for patterns. Reflect on what can be changed in the physical environment, schedule/routine, groupings, and supervision to help prevent children from hurting themselves or others when trying to communicate their needs.

Biting

Biting is a common but upsetting behaviour of toddlers. Here is some information and tips for responding to biting:

When a child bites another child

- Intervene immediately between the child who bit and the bitten child. Stay calm don’t overreact, yell or give a lengthy explanation.

- Use your voice and expression to show that biting is not acceptable. Look into the child’s eyes and say calmly but firmly, “I do not like it when you bite people.” For a child with more limited language, just say “No biting people.” Point out how the biter’s behaviour affected the other person. “You hurt him and he’s crying.” Encourage the child who was bitten to tell the biter “You hurt me.” Encourage the child who bit to help the other child by getting the ice pack, etc.

- Offer the bitten child comfort and first aid. Wash broken skin with warm water and soap. Observe general precautions if there is bleeding. Apply an ice pack or cool cloth to help prevent swelling. If the bitten child is a guest, tell the families what happened. Suggest the bitten child be seen by a health care provider if the skin is broken or there are any signs of infection (redness or swelling).

Preventing biting

- Reinforce desired behaviour. Notice and acknowledge when you like what your child is doing, especially for showing empathy or social behaviour, such as patting a crying child, offering to take turns with a toy or hugging gently. Do not label, humiliate or isolate a child who bites.

- Discourage play which involves “pretend” biting, or seems too rough and out of control. Help the child make connections with others.

Why do children bite and what can we do?

Children bite for many different reasons, so in order to respond effectively, it’s best to try and find out why they are biting.

- If a child: experiments by biting immediately say “no” in a firm voice, and give him a variety of toys to touch, smell and taste and encourage sensory-motor exploration.

- has teething discomfort, provide cold teething toys or safe, chewy foods.

- is becoming independent, provide opportunities to make age-appropriate choices and have some control (the bread or the cracker, the yellow or the blue ball), and notice and give positive attention as new self-help skills and independence develop.

- is using muscles in new ways, provide a variety of play materials (hard/soft, rough/smooth, heavy/light) and plan for plenty of active play indoors and outdoors.

- Is learning to play with other children, try to guide behaviour if it seems rough (take the child’s hand and say, “Touch Jorge gently—he likes that”) and reinforce prosocial behaviour (such as taking turns with toys or patting a crying child).

- is frustrated in expressing his/her needs and wants, state what she is trying to communicate (“you feel mad when Ari takes your truck” or “you want me to pay attention to you”).

- is threatened by new or changing situations such as a parent returning to work, a new baby, or parents/caregivers separating, provide special nurturing and be as warm and reassuring as possible, and help him or her talk about feelings even when he or she says things like “I hate my new baby.” [12]

Safe Toys, Materials, and Equipment

Play is a natural activity for every young child. Play provides many opportunities for children to learn and grow – physically, mentally, and socially. If play is the child’s work, then the toys, materials, and equipment in the environment are what will enable children to do their work well and safely.[13][/footnote]

Safe Toys

Protecting children from unsafe toys is the responsibility of everyone. Careful toy selection and proper supervision of children at play are still—and always will be—the best ways to protect children from toy-related injuries. [14]

It is important that educators consider both safety and durability when choosing toys for children. Toys should be constructed to withstand the uses and abuses of children in the age range for which the toy is appropriate.

The U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) has safety regulations for certain toys. Manufacturers must design and manufacture their products to meet these regulations so that hazardous products are not sold (see Table 3.3).

Table 3.3 – Mandatory Toy Safety Regulations [15] |

|

| Age | Regulations |

| For All Ages | No shock or thermal hazards in electrical toys. Amount of lead paint is severely limited. No toxic materials in or on toys. All materials for children 12 and under are non-hazardous. Latex balloons and product with balloons are labeled as choking and suffocation hazard. |

| Under Age 3 | Unbreakable – will withstand use and abuse. No small parts or pieces which become lodged in throat. Rattles large enough not to become lodged in the throat and will not separate into small pieces. No balls with diameters 1.75 inches or less. |

| Ages 3-6 | All toys and games with small parts must be labeled to warn of the choking hazard to young children. |

| For 3 years and older | Ball and toys with balls smaller than 1.75 inches in diameter and marbles or toys with marbles must be labeled to warn of the choking hazard. |

| Under Age 8 | No electrically operated toys with heating elements. No sharp points or edges on toys. |

In addition to the mandatory standards, many toy manufacturers also adhere to the toy industry’s voluntary safety standards. [16]

Voluntary Standards for Toy Safety [17]

Puts age and safety labels on toys. Puts warning labels on crib gyms advertising that they should be removed from cribs when infants can push up on hands and knees to prevent strangulation. Makes squeeze toys and teethers large enough not to become lodged in an infant’s throat. Assures that the lid of a toy chest will stay open in any position to which it is raised and not fall unexpectedly on a child. Limits string length on crib and playpen toys to reduce the risk of strangulation.

Toys should be chosen with care. Teachers should look for quality design and construction. Safety labels to look for include “Flame retardant/Flame resistant” on fabric products and “Washable/hygienic materials” on stuffed toys and dolls. Watch for the hazards listed in Table 3.5 [18]

Table 3.5 – Hazards to Avoid in Toys [19] |

|

| Hazards | Description |

| Sharp Edges | New toys intended for children under eight years of age should be free of sharp glass and metal edges. With use, however, older toys may break, exposing cutting edges. |

| Small Parts | The law bans small parts in toys intended for children under three. This includes removable small eyes and noses on stuffed toys and dolls and small, removable squeakers on squeeze toys. |

| Loud Noises | Some noise-making toys can produce sounds at noise levels that can damage hearing. |

| Cords And Strings | Toys with long strings or cords are dangerous for infants and very young children. The cords can become wrapped around an infant’s neck, causing strangulation. Never hang toys with long strings, cords, loops, or ribbons in cribs or playpens where children can become entangled. Remove crib gyms from the crib when the child can pull up on hands and knees; some children have strangled when they fell across crib gyms stretched across the crib. |

| Sharp Points | Toys that have been broken may have dangerous points or prongs. Stuffed toys may have wires inside the toy which could cut or stab if exposed. A CPSC regulation prohibits sharp points in new toys and other articles intended for use by children under eight years of age. |

| Propelled Objects | Projectiles—guided missiles and similar flying toys—can be turned into weapons and can injure eyes in particular. Children should never be permitted to play with hobby or sporting equipment that has sharp points. |

Check all toys periodically for breakage and potential hazards. A damaged or dangerous toy should be thrown away or repaired immediately.

Age Appropriate Toys

Teachers must keep in mind the ages of children they are choosing toys for, including their typical interests and skill levels. The manufacturer’s age recommendation is a good starting place to ensure that toys are age-appropriate. Warnings such as “Not recommended for children under 3” should be followed. [20]

See Table 3.6 for some age-appropriate toys to consider. Please note that toys appear on the list when they become appropriate and are not repeated in later ages.

| Table 3.6 – Age Appropriate Toys[21] | |

| Age | Some Age Appropriate Toys |

| From 6 weeks to around 4 months these toys become appropriate | Simple rattles Teethers Light, sturdy cloth toys and dolls Squeeze toys Texture and soft squeeze balls |

| Between 4 to 6 months these toys become appropriate | Soft blocks Keys on rings Interlocking plastic rings Small hand-held manipulatives Toys on suction cups |

| Between 7 to 12 months these toys become appropriate | Rubber or rounded wood blocks Push toys (simple cars, animals on wheels, etc.) Squeeze-squeak toys Roly-poly toys Activity boxes and cubes Containers with objects to empty and fill Transparent, chime, flutter, and action balls Large rubber or plastic pop beads Simple nesting cups Stacking rings Graspable unbreakable mirror toys Simple floating toys Paper and large crayons for scribbling Cloth, plastic, and board books |

| These toys become appropriate for 1-year-olds | In addition to above Push toys with large handles Toys to push on the floor Doll carriages and wagons Stable ride-on toys with no pedals Small stacking blocks Unit blocks Hollow blocks Large plastic bricks to press together Simple puzzles (at 1, 2-3 pieces and 1½, 3-5 pieces) Pegboards with large pegs Hidden object toys Simple pop-up toys Simple shape sorters Pounding and hammering toys Simple matching toys Simple lock boxes and toys Large beads for stringing Funnels and colanders Small sand toys Dolls and simple accessories Rhythm instruments operated by shaking and banging Simple dress-up clothes and role-play toys Child-sized dramatic play equipment Picture books More detailed toy vehicles Trains with simple coupling systems |

| These toys become appropriate for 2-year-olds | Pull toys Small, light-weight wheelbarrows Push toys that look like adult equipment (lawnmower, vacuum, etc.) Small tricycles 4 to 5 and then 6-12 piece puzzles Magnetic boards with shapes, animals, nd people Fit together toys Large balls Smelling jars Feeling bags Lacing cards Frames for buttoning, lacking, snapping, and hooking Small boats Water/sand mills More realistic dolls Small hand puppets All rhythm instruments Non-toxic paints Clay Markers Blunt-end scissors Chalk and chalkboard Costumes and dress-up clothing Realistic dramatic play props Larger trucks and construction vehicles Pop-up books Hidden picture books |

| These toys become appropriate at around 3 years of age | Fit in frame puzzles up to 20 pieces Simple jigsaw puzzles Number boards with smaller pegs Frames to tie Large sandbox tools Realistic dolls Stuffed toys with accessories Music box toys Simple sock, mitten, and finger puppets Toy telephone, camera, doctor kit Cash register and equipment to play store Xylophone Paintbrushes Paste and glue Simple block printing Simple board, lotto, and card games |

| These toys become appropriate around 4 years of age | Mosaic boards Felt boards Matching toys Geometrical concept toys Sand molds Wood-working tools Audio equipment |

| These toys become appropriate around 5 years of age | Simple weaving loom Simple sewing kit (with a blunt-tipped needle) Paper dolls Dramatic play equipment that works Watercolour paint Science materials Toy typewriter |

Pause to Reflect

Look at these toys that might be given to children.

- Do you know enough about them to know whether or not they are safe?

- If not, what would you need to know and do to make sure they are safe?

- How would you determine what age of children they are safe for?

|

Image is in the public domain. |

Image is in the public domain. |

Nontoxic Art Materials

Federal law requires that all art materials offered for sale to consumers of all ages in the United States undergo a toxicological review of the complete formulation of each product to determine the product’s potential for producing adverse chronic health effects. It also requires that the art materials be properly labeled for acute and chronic hazards, as required by the Labeling of Hazardous Art Materials Act(LHAMA) and the Federal Hazardous Substances Act (FHSA), respectively.

In addition to the LHAMA requirements, art materials – such as paintbrushes and stencils – that are designed or intended primarily for children 12 years of age or younger, are also required, like all children’s products, to comply with the requirements of the Consumer Product Safety Improvement Act of 2008 (CPSIA). [22]Under the FHSA, most children’s products that contain a hazardous substance are banned, whether the hazard is based on chronic toxicity, acute toxicity, flammability, or other hazard identified in the statute.

Children’s products that meet the FHSA’s definition of an art material include, but are not limited to, crayons, chalk, paint sets, coloured pencils, and modeling clay. Non-toxic art and craft supplies intended for children are readily available. Read the labels and only purchase art and craft materials intended for children and that are labeled with the statement “Conforms to ASTM D-4236.” [23]

One such label will come from the Art and Creative Materials Institute’s (ACMI) certification program. “ACMI-certified product seals…indicate that these products have been evaluated by a qualified toxicologist and are labeled in accordance with federal and state laws… The AP (Approved Product) Seal identifies art materials that are safe and that are certified in a toxicological evaluation by a medical expert to contain no materials in sufficient quantities to be toxic or injurious to humans, including children, or to cause acute or chronic health problems.” [25]

Pause to Reflect

Look at each of the labels of art supplies.

- Can you find the label or seal on each?

- Can you find the warning on one of these materials that you would want to pay attention to if purchasing it to use with young children?

Safety Risks from Art Materials

For certain chemicals and exposure situations, children may be especially susceptible to the risk of injury. For example, since children are smaller than adults, children’s exposures to the same amount of a chemical may result in more severe effects. Further, children’s developing bodies, including their brains, nervous systems, and lungs may make them more susceptible than adults. Differences in metabolism may also affect children’s responses to some chemicals.

Children‘s behaviours and cognitive abilities may also influence their risk. For example, children under the age of 12 are less able to remember and follow complex steps for safety procedures, and are more impulsive, making them more likely to ignore safety precautions. Children have a much higher chance of toxic exposure than adults because they are unaware of the dangers, not as concerned with cleanliness and safety precautions as adults, and are often more curious and attracted to novel smells, sights, or sounds. Children need regular and consistent reminders of safety rules, and there is no substitute for direct supervision.

Guidelines for Selecting Art and Craft Materials

Here are some helpful reminders about choosing art materials for children:

- Note that even products labeled ‘non-toxic’ when used in an unintended manner can have harmful effects.

- Products with cautionary/warning labels should not be used with children under age 12.

- Avoid solvents and solvent-based supplies, which include turpentine, paint thinner, shellac, and some glues, inks, and a few solvent-containing permanent markers.

- Avoid products or processes that produce airborne dust that can be inhaled (including powdered tempera paint).

- Avoid old supplies, unlabeled supplies, and be wary of donated supplies with cautionary/warning labels and that do not contain the statement “Conforms to ASTM D4236.”

- Look for products that are clearly labeled with information about intended uses.

- Give special attention to students with asthma or allergies, which may elevate the students’ sensitivities to fumes, dust, or products that come into contact with the skin. [26]

- Gather your supplies beforehand so that you can continue to supervise their use without needing to step away.

- Instruct children on safety practices before you begin (such as, modeling how to cut safely with scissors).

- Do activities in well-ventilated areas.

- Use protective equipment (such as smocks).

- Assume that anything you use should be safe enough that it won’t harm children if it gets on their skin or in their mouths and/or eyes. [27]

Using Technology and Media Safely

Developmentally appropriate use of technology can help young children grow and learn, especially when families and early educators play an active role. Early learners can use technology to explore new worlds, make-believe, and actively engage in fun and challenging activities. They can learn about technology and technology tools and use them to play, solve problems, and role play. But how technology is used is important to protect children’s health and safety.

Technology can be a Tool for Learning

What exactly is developmentally appropriate when it comes to technology for children? In Technology and Interactive Media as Tools in Early Childhood Programs Serving Children from Birth through Age 8, the National Association for the Education of Young Children (NAEYC) and the Fred Rogers Center state that “appropriate experiences with technology and media allow children to control the medium and the outcome of the experience, to explore the functionality of these tools, and pretend how they might be used in real life.” [28]

Lisa Guernsey, author of Screen Time: How Electronic Media—From Baby Videos to Educational Software—Affects Your Young Child, also provides guidance for families and early educators. For example, instead of applying arbitrary, “one-size-fits-all” time limits, families and early educators should determine when and how to use various technologies based on the Three C’s: the content, the context, and the needs of the individual child. They should ask themselves the following questions:

- Content—How does this help children learn, engage, express, imagine, or explore?

- Context—What kinds of social interactions (such as conversations with families or peers) are happening before, during, and after the use of the technology? Does it complement, and not interrupt, children’s learning experiences and natural play patterns?

- The individual child—What does this child need right now to enhance his or her growth and development? Is this technology an appropriate match with this child’s needs, abilities, interests, and development stage? [29]

Early childhood educators should keep in mind the developmental levels of children when using technology for early learning. That is, they first should consider what is best for healthy child development and then consider how technology can help early learners achieve learning outcomes. Technology should never be used for technology’s sake. Instead, it should only be used for learning and meeting developmental objectives, which can include being used as a tool during play.

When technology is used in early learning settings, it should be integrated into the learning program and used in rotation with other learning tools such as art materials, writing materials, play materials, and books, and should give early learners an opportunity for self-expression without replacing other classroom learning materials. There are additional consi

derations for educators when technology is used, such as whether a particular device will displace interactions with teachers or peers or whether a device has features that would distract from learning. Further, early educators should consider the overall use of technology throughout a child’s day and week, and adhere to recommended guidelines from the Let’s Move initiative, in partnership with families. Additionally, if a child has special needs, specific technology may be required to meet that child’s educational and care needs. And dual language learners can use digital resources in multiple languages or translation to support both their home language and English development.

For Infants and Toddlers

Research shows that unstructured playtime is particularly important for infants and toddlers because they learn more quickly through interactions with the real world than they do through media use and, at such a young age, they have limited periods of awake time. At this age, children require “hands-on exploration and social interaction with trusted caregivers to develop their cognitive, language, motor, and social-emotional skills.”

For children under the age of 2, technology use in early learning settings is generally discouraged. But if determined appropriate by the IFSP team under Part C of the IDEA, children with disabilities in this age range may also use technology, for example, an assistive technology device to help them communicate with others, access and participate in different learning opportunities, or help them get their needs met.

For Preschoolers

For children ages 2-5, families and early educators need to take into account that technology may be used at home and in early learning settings. New recommendations in the AAP’s 2016 Media and Young Minds Brief suggest that one hour of technology use is appropriate per day, inclusive of time spent at home and in early learning settings and across devices. [31]The Department of Health and Human Services supports more limited technology use in early care settings, and more information on their recommendations can be found in Caring for Our Children: National Health and Safety Performance Standards. [32]However, time is only one metric that should be considered with technology use for children in this age range. Early educators should also consider the quality of the content, the context of use, and opportunities the technology provides to strengthen or develop relationships.

For School-Aged Children

For children ages 6-8 in school settings, technology should be used as a tool for children to explore and become active creators of content. If children have more than one teacher, those teachers should be aware of how much screen time is being used across subject areas and at home. Students should learn to use technology as an integrated part of a diverse curriculum.

Active versus Passive Engagement

Early childhood educators should understand the differences between passive and active use of technology. Passive use of technology generally occurs when children are consuming content, such as watching a program on television, a computer, or a handheld device without accompanying reflection, imagination, or participation.

Active use occurs when children use technologies such as computers, devices, and apps to engage in meaningful learning or storytelling experiences. Examples include sharing their experiences by documenting them with photos and stories, recording their own music, using video chatting software to communicate with loved ones, or using an app to guide playing a physical game. These types of uses are capable of deeply engaging the child, especially when an adult supports them. While actions such as swiping or pressing on devices may seem to be interactive, if the child does not intentionally learn from the experience, it is not considered to be active use. To be considered active use, the content should enable deep, cognitive processing, and allow intentional, purposeful learning at the child’s developmental level.

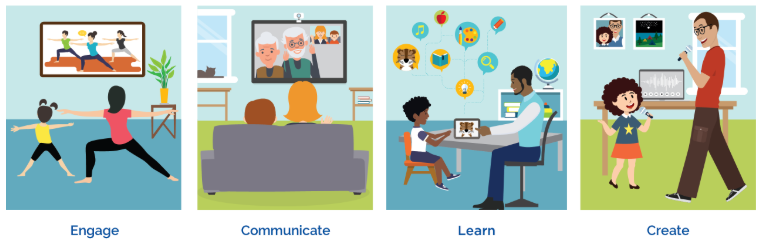

Exercises

- Do these children look like they are using technology actively or passively?

- What do you need to see or know to accurately make this determination?

Early childhood educators also need to think of ways they can reduce the sedentary nature of most technology use. Technology can encourage and complement physical activity, such as doing yoga with a video or learning about the plants outdoors with a nature app.

The Digital Divide

Research points to a widening digital use divide, which occurs when some children have the opportunity to use technology actively while others are asked primarily to use it passively. The research showed that children from families with lower incomes are more likely to complete passive tasks in learning settings while their more affluent peers are more likely to use technology to complete active tasks.

For low-income children who may not have access to devices or the internet at home, early childhood settings provide opportunities to learn how to use these tools more actively. For example, research shows that preschool-aged children from low-income families in an urban Head Start center who received daily access to computers and were supported by an adult mentor displayed more positive attitudes toward learning, improved self-esteem and self-confidence, and increased kindergarten readiness skills than children who had computer access but did not have support from a mentor.

Co-Viewing of Technology

Most research on children’s media usage shows that children learn more from content when parents/caregivers or early educators watch and interact with children, encouraging them to make real-world connections to what they are viewing both while they are viewing and afterward.

There are many ways that adult involvement can make learning more effective for young children using technology. Adult guidance that can increase active use of more passive technology includes, but are not limited to, the following:. Prior to the child viewing content, an adult can talk to the child about the content and suggest certain elements to watch for or pay particular attention to;. An adult can view the content with the child and interact with the child in the moment;. After a child views the content, an adult can engage the child in an activity that extends learning such as singing a song they learned while viewing the content or connecting the content to the world.

Safety Risks of Technology

In addition to the health risks of sedentary activity (in place of active play), there are concerns about privacy and security with any technology. The rights of children under 13 and technology in school are governed by federal laws, but looking at privacy policies is important.

Software and apps may also include advertising and in-app purchasing (generally inappropriate for young children). So early childhood educators should choose software and apps that avoid advertising and in-app purchases.

What is Digital Citizenship?

Digital citizenship is defined as “a set of norms and practices regarding appropriate and responsible technology use… and requires a whole-community approach to thinking critically, behaving safely, and participating responsibly online.” [36]

As early learners reach an appropriate age to use technology more independently, they must be taught about cyber safety, including the need to protect and not share personal information on the internet, the goals and influence of advertisements, and the need for caution when clicking on links. These skills are particularly important for older children who may be using a parent’s device unsupervised. Early childhood educators and administrators should ensure that the proper filters and firewalls are in place so children cannot access materials that are not approved for a school setting. [37]

Not all technology is appropriate for young children and not every technology-based experience is good for young children’s development. To ensure that technology has a positive impact, adults who use technology with children should continually update their knowledge and equip themselves to make sophisticated decisions on how to best leverage these technology tools to enhance learning and interpersonal relationships for young children.

Access to technology for children is necessary in the 21st century but not sufficient. To have beneficial effects, it must be accompanied by strong adult support. [38]

Preventing Injuries Indoors

Some injuries that early childhood educators should be aware of and intentionally act to prevent in the last chapter were presented in the previous chapter and earlier in this chapter during the discussion about safe toys and art materials. Here is some further information about injuries that are more likely to happen indoors.

Choking

Choking occurs when an object blocks the airway, preventing breathing.[54] Infants have the highest rates of choking (140 per 100,000). That risk decreases as they get older and their airway increases in size, with 90% of fatal choking happening in children less than 4 years of age.[55]

Reducing the Risks of Choking

The main way to prevent choking is to recognize that objects that are 1½ inches or less in diameter are higher risk. [56] Foods are the most common cause of choking. Having children sit during snacks and meals at an unhurried pace, allowing time for children to properly chew their food helps prevent choking on food. Food is safest when cut into small pieces or served in small amounts. See Table 3.7 for foods that commonly cause choking.

| Table 3.7 – Common Choking Hazards [57] | |

| Foods | Other Items |

| Cubed cheese Fruits (especially when the skin is left on) Peanut butter Popcorn Pretzels Raisins Vegetables (especially when raw) Ice cubes Candy |

Balloons Batteries Coin Bottle caps Small balls Office supplies |

Toys, and other items that children may play with, are another common source of choking hazards. Ensuring children only have access to age-appropriate toys is an important step. See Table 3.7 for items that should be kept out of reach of young children.Teachers can use a small parts tester, a commercial product commonly known as choke tube, to test whether or not an object is a choking hazard. Recognizing and responding to choking will be addressed in Chapter 5.[58]

Poisoning

There are many hazards that put children at risk for accidental poisoning, both indoors and outdoors. Poisoning can occur at any time a harmful substance is intentionally or unintentionally ingested. Poisons come in many forms including plants, cleaning supplies, spoiled food, and medications. Children, who are naturally curious and like to explore, are in particular at risk for poisoning.

Guidelines to Prevent Poisoning. Keep all cleaning supplies and chemicals locked.. All medications should be kept in a locked storage area, out of reach.. Check medications periodically for expiration dates and properly dispose of expired medications. Some medications become toxic when they are past their expiration date.. Do not tell children that medication is “candy” as this makes it look more attractive to them.. Ensure all medications and chemicals are properly labeled. Childproof caps should be on medicine bottles.. Use safe food practices. (see Chapter 15). Never use cans that have bulges or deep dents in them.. Keep poisonous plants out of reach of children and pets. (see Table 3.8). Keep the number for Poison Control near a telephone. [40]

| Table 3.8 Poisonous Plants [42] | |

| Common Name | Botanical Name |

| Azalea, rhododendron | Rhododendron |

| Caladium | Caladium |

| Castor bean | Ricinis communis |

| Daffodil | Narcissus |

| Deadly nightshade | Atropa belladonna |

| Dumbcane | Dieffenbachia |

| Elephant Ear | Colocasia esculenta |

| Foxglove | Digitalis purpurea |

| Fruit pits and seeds | contain cyanogenic glycosides |

| Holly | Ilex |

| Iris | Iris |

| Jerusalem cherry | Solanum pseudocapsicum |

| Jimson weed | Datura stramonium |

| Lantana | Lantana camara |

| Lily-of-the-valley | Convalleria majalis |

| Mayapple | Podophyllum peltatum |

| Mistletoe | Viscum album |

| Morning glory | Ipomoea |

| Mountain laurel | Kalmia iatifolia |

| Nightshade | Salanum spp. |

| Oleander | Nerium oleander |

| Peace lily | Spathiphyllum |

| Philodendron | Philodendron |

| Pokeweed | Phytolacca americana |

| Pothos | Epipremnum aureum |

| Yew | Taxus |

Burns

Every day, over 300 children ages 0 to 19 are treated in emergency rooms for burn-related injuries and two children die as a result of being burned.

Younger children are more likely to sustain injuries from scald burns that are caused by hot liquids or steam, while older children are more likely to sustain injuries from flame burns that are caused by direct contact with fire. [63]

Causes of Burns

- Burns can be caused by dry or wet heat, chemicals, or electricity (both indoors and outdoors).

- Burns from dry heat can occur from fire, irons, hairdryers, curling irons, and stoves (American Institute for Preventive Medicine, 2012; Leahy, Fuzy & Grafe, 2013).

- Burns from wet or moist heat occur from hot liquids, such as hot water or steam (American Institute for Preventive Medicine; Leahy, Fuzy & Grafe). These types of burns are called scalds. Scalds can occur within seconds and cause serious injury.

- Chemical burns occur from chemical sources and can also cause serious burns when exposed to skin, or if swallowed, whether intentionally or unintentionally.

- Electrical burns can cause very serious injury as they can burn both the outside and inside of the person’s body, causing injury that cannot be seen, and which can be life-threatening.

- Radiation burns can also occur from sources of radiation such as sunlight (American Institute for Preventive Medicine). [43]

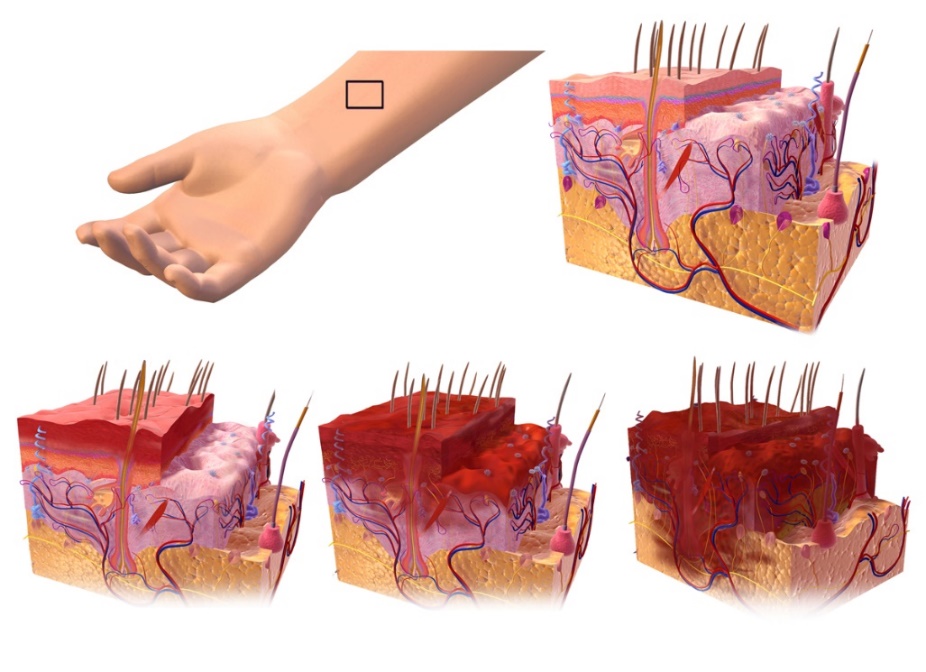

Types of Burns

Burns are divided into first, second, and third degree burns.

First degree burns affect only the outer layer of the skin (epidermis). These types of burns are the least serious as they are only on the surface of the skin. First degree burns usually appear red, dry, and slightly swollen (MedlinePlus, 2014). Blisters do not occur with this type of burn. They should heal within a couple of days (American Institute for Preventive Medicine, 2012). A first degree burn is pictured in the bottom left of Figure 3.20.

Second degree burns affect the top layer of the skin and the second layer of skin underneath (dermis). These are more serious than first degree burns. The skin may appear very swollen, red, moist, (MedlinePlus, 2014) and may have blisters or look watery and weepy (American Institute for Preventive Medicine, 2012). A second degree burn is pictured in the bottom middle of Figure 3.20.

Third degree burns are the most serious burn. A third degree burn affects all layers of the skin and may affect the organs below the surface of the skin. The skin may appear white or black and charred (MedlinePlus, 2014). The person may deny pain because the nerve endings in their skin have been burned away (American Institute for Preventive Medicine, 2012). Third degree burns require immediate medical treatment. If teachers suspect a child has a third degree burn, they should immediately call 911. A third degree burn is pictured in the bottom right of Figure 3.20. [44]

Chemical burns can occur anytime a liquid or powder chemical comes into contact with skin or mucous membranes that line the eyes, nose, or throat. Chemical burns may also occur if a chemical is swallowed. These burns can cause serious injury and emergency services should be contacted. If a person receives a chemical burn, the chemical should be removed from the skin by using a gloved hand to brush it off and then wash the area with plenty of cool water. Electrical burns can occur if a person has been using an electrical appliance and is exposed to water or if an electrical short occurs while using the electrical appliance. Using faulty or frayed cords on electrical appliances can result in electrical burns. Electrical burns are a serious injury. Emergency medical services (EMS) should be immediately activated.

Never use oils such as butter or vegetable oil on any type of burn as this can cause further injury. For first or second degree burns flush the area with plenty of cool (not ice cold) water for about 15 minutes or until the pain decreases and cover with a clean, dry bandage. Using ice or ice-cold water can cause frostbite (American Institute for Preventive Medicine, 2012). For major burns remove any clothing that is not stuck to the skin, cover the burned area with a dry, clean cloth, and seek emergency assistance. [46]

Guidelines to Prevent Burns

- Install and regularly test smoke alarms.

- Practice fire drills. [68]

- Train staff to use fire extinguishers.

- Teach children to stop, drop, and roll.[69]

- Never allow children to use electrical appliances unsupervised.

- Never use electrical appliances near water sources.

- Never use electrical appliances in which the cord appears to be damaged or frayed.

- Never pull a plug from the cord. Always remove a cord from an outlet by holding the base of the plug.

- Cover electrical outlets with childproof plugs. Never allow children to put anything inside an electrical outlet.

- Ensure stoves and other appliances are turned off when finished with them.

- Turn pot handles inward so that a person cannot accidentally bump a handle and spill hot liquids.

- Do not use space heaters and other personal heaters.

- Check to be sure the hot water heater is not set too high. To avoid scalds from hot tap water, hot water heaters should be set to 120 degrees or less (MedlinePlus, 2014).

- Keep chemicals, cleaning solutions, and matches and lighters securely locked and out of reach of children. [47]

Safe Sleeping

Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS) is identified when the death of a healthy infant occurs suddenly and unexpectedly, and medical and forensic investigation findings (including an autopsy) are inconclusive. SIDS is the leading cause of death in infants 1 to 12 months old, and approximately 1,500 infants died of SIDS in 2013 (CDC, 2015). Because SIDS is diagnosed when no other cause of death can be determined, possible causes of SIDS are regularly researched. One leading hypothesis suggests that infants who die from SIDS have abnormalities in the area of the brainstem responsible for regulating breathing (Weekes-Shackelford & Shackelford, 2005). [48]

This is a very important topic for early childhood educators as one study found that while data suggests that only 7% of incidents of SIDS should occur while children are in child care, 20.4% actually did. [49]

Risk Factors for SIDS

Babies are at higher risk for SIDS if they:

- Sleep on their stomachs.

- Sleep on soft surfaces, such as an adult mattress, couch, or chair or under soft coverings.

- Sleep on or under soft or loose bedding.

- Get too hot during sleep.

- Are exposed to cigarette smoke in the womb or in their environment, such as at home, in the car, in the bedroom, or other areas.

- Sleep in an adult bed with parents/caregivers, other children, or pets; this situation is especially dangerous if:

- The adult smokes, has recently had alcohol, or is tired.

- The baby is covered by a blanket or quilt.

- The baby sleeps with more than one bed-sharer.

- The baby is younger than 11 to 14 weeks of age.

Important Facts About SIDS

- SIDS happens in families of all social, economic and ethnic groups.

- Most SIDS deaths occur between one and four months of age.

- SIDS occurs in boys more than girls.

- The death is sudden and unexpected, often occurring during sleep. In most cases, the baby seems healthy.

- Although it is not known exactly what causes SIDS, researchers know that it is not caused by suffocation, choking, spitting up, vomiting, or immunizations.

- SIDS is not contagious.[74]

Reducing the Risks

Although the sudden and unexpected death of an infant cannot be predicted or prevented, research shows that certain infant care practices can help reduce the risk of a baby dying suddenly and unexpectedly. Early childhood educators can help lower the risk of SUID for infants less than one year of age by following these risk reduction guidelines.

Sleeping Position

The chance of an infant dying suddenly and unexpectedly in childcare is higher when a baby first starts the transition from home to care. Research shows if a baby has been placed on his/her back by the families, and the childcare provider places the baby to sleep on his/her stomach, there is a higher risk of death in the first weeks of child care. One of the most important things you can do to reduce the risk of sudden unexpected death is to place babies to sleep on their backs.

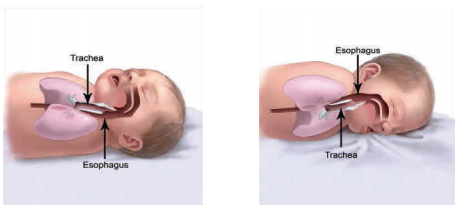

Healthy babies do not choke when placed to sleep on their backs. By reflex, babies swallow or cough up fluids to keep the airway clear. Since the windpipe (trachea) is positioned on top of the esophagus, fluids are not likely to enter the airway. (See Figure 3.21)

Babies who are able to roll back and forth between their back and tummy should be placed on their backs for sleep and allowed to assume their sleep position of choice. When infants fall asleep while playing on their tummies, move the baby to a crib onto his/her back to continue sleeping.

Cribs, Sleep Surface and Bedding

Infants should sleep in a crib, bassinet, portable crib or play yard that conforms to the safety standards of the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC). The mattress should be firm, fit tightly, and be covered with a tight fitted sheet. Babies should not sleep on adult beds, waterbeds, couches, beanbag chairs or other soft surfaces. Do not use fluffy blankets or comforters under the baby, or put the baby to sleep on a sheepskin, pillow or other soft materials. Keep stuffed toys, bumper pads, loose bedding and other toys and soft objects out of the crib.

Temperature

Babies should be kept warm, not hot. Babies should be dressed with only one additional layer than you are wearing for warmth. In areas where babies sleep, keep the temperature so that it feels comfortable to you. If needed, infants can be dressed in blanket sleepers for warmth. This ensures that the baby’s head will be uncovered during sleep.

Smoke Free

No one should smoke around children. California Child Care Licensing Regulations prohibit smoking in childcare centers. Smoke in the infants’ environment is a major risk factor for SIDS.

Pacifiers

If the family provides a pacifier, it should be offered to the infant. If a pacifier is used, it should never be attached to a string. Infants should not be forced to take a pacifier and if it falls out during sleep it doesn’t need to be given back to the infant.

Breastfeeding

Breastfeeding has many health benefits for mother and baby, including a reduced risk of SIDS. Childcare programs should be breastfeeding friendly. [76]

Other Things Caregivers and Teachers Can Do To Reduce the Risks

- Families should be asked about their infant’s usual sleep position. Teachers should discuss the recommended back sleeping position with families and share the program’s policy is to place infants on their back to sleep.

- Policies should be developed to address sleep position. If a family insists their baby sleep on the side or stomach, they should be referred to their health care provider for further information. Programs should request that a medical care professional provide a signed statement for infants who have a medical reason for not being placed to sleep on their backs.

- Teachers can attend education programs to learn more about sudden unexpected infant deaths. Training and education for childcare providers may be available through local public health Resource and Referral agency or Public Health Department at no cost.

- Programs should be aware of resources for additional support and make them available to families as appropriate. It is vital to stay up‐to‐date with the latest recommendations for safe infant sleep.

- For education and informational materials, contact the California SIDS Program: 800‐369‐SIDS (7437).[77]

Indoor Falls

While most falls occur outdoors, and this topic is addressed in Chapter 4, they can also happen indoors. Teachers (and adults at home) can prevent falls indoors by:

- Installing stops on windows that prevent them from being opened more than four inches or install window guards on lower parts of windows. Removing furniture from near windows. Screens should not be relied on to prevent a fall.

- Installing safety gates at the top and bottom of staircases. Installing lower rails on stairs that children can reach and use. Making sure the surface of the stairs stays clear.

- Using safety straps and harnesses on baby equipment and furniture. Children should not be left unattended in high chairs or on changing tables.

- Baby walkers should not be used (licensing prohibits these).

- Teaching children to walk where surfaces may be slick. Preventing these surfaces as much as possible, such as wiping up spills.[78]

Indoor Water Safety

Small children are top-heavy; they tend to fall forward and headfirst when they lose their balance. They do not have enough muscle development in their upper body to pull themselves up out of a bucket, toilet or bathtub, or for that matter, any body of water. Even a bucket containing only a few inches of water can be dangerous for a small child.

It’s important that early childhood educators follow the safety practices outlined in Chapter 4 for water safety both indoors and outdoors, keep children under active supervision, and be very aware of containers of water.[79]

Pause to Reflect

- What are your top five tips for protecting children from safety hazards indoors?

- These can relate to toy safety, safe art materials, preventing poisoning, preventing choking, preventing burns, safe sleep, protecting from indoor falls, water safety, or any other hazard/area of safety.

Summary

Teachers need to create safe indoor environments in which children engage, explore, and interact. By recognizing that behaviour is communication, they can help children use safe behaviours to get their needs met. Teachers should choose age-appropriate toys and materials that are well constructed, hazard-free, and nontoxic. With adult support, children can navigate media and technology safely. Teachers must work to prevent injuries that may occur indoors, such as choking, poisoning, burns, drowning, and falls. And teachers that care for infants must follow practices to reduce the risk of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome.

Chapter 3 Review

Resources for Further Exploration

- U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission

- Center on the Social and Emotional Foundations for Early Learning:

- Technical Assistance Center on Social Emotional Intervention for Young Children

- Guiding Principles for Use of Technology with Early Learners:

- Common Sense Media

- Child Injury Prevention

- What Child Care Providers and Other Caregivers Should Know: Sudden Unexpected Infant Deaths

- Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS) Program

References:

[11] Behavior Has Meaning: Presenter Notes by the National Center on Early Childhood Health and Wellness is in the public domain.

[12] Form and Function by the National Center on Early Childhood Health and Wellness is in the public domain.

[13] Behavior Has Meaning: Presenter Notes by the National Center on Early Childhood Health and Wellness is in the public domain.

[14] Form and Function by the National Center on Early Childhood Health and Wellness is in the public domain.

[15] Behavior Has Meaning: Presenter Notes by the National Center on Early Childhood Health and Wellness is in the public domain.

[54] Anderson, K. (2020). Choking: Knowing the Signs and What to Do. Retrieved from https://www.chla.org/blog/rn-remedies/choking-knowing-the-signs-and-what-do

[55] American Academy of Pediatrics. (2020). Safety and Injury Prevention Curriculum. Retrieved from https://www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/aap-health-initiatives/healthy-child-care/Pages/Safety-and-Injury-Prevention.aspx

[56] American Academy of Pediatrics. (2020). Safety and Injury Prevention Curriculum. Retrieved from https://www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/aap-health-initiatives/healthy-child-care/Pages/Safety-and-Injury-Prevention.aspx

[57] Anderson, K. (2020). Choking: Knowing the Signs and What to Do. Retrieved from https://www.chla.org/blog/rn-remedies/choking-knowing-the-signs-and-what-do

[58] Anderson, K. (2020). Choking: Knowing the Signs and What to Do. Retrieved from https://www.chla.org/blog/rn-remedies/choking-knowing-the-signs-and-what-do

[63] Burn Prevention by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the public domain

[68] Burn Prevention by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the public domain.

[69] Mayo Clinic. (2019). Burn Safety: Protect your child from burns. Retrieved from: https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/infant-and-toddler-health/in-depth/child-safety/art-20044027

[74] California Dept. of Public Health MCAH. (2014). What Child Care Providers and Other Caregivers Should Know. Retrieved from https://cchealth.org/sids/pdf/Child-Care-SIDS-Booklet.pdf.

[75] California Dept. of Public Health MCAH. (2014). What Child Care Providers and Other Caregivers Should Know. Retrieved from https://cchealth.org/sids/pdf/Child-Care-SIDS-Booklet.pdf.

[76] California Dept. of Public Health MCAH. (2014). What Child Care Providers and Other Caregivers Should Know. Retrieved from https://cchealth.org/sids/pdf/Child-Care-SIDS-Booklet.pdf.

[77] California Dept. of Public Health MCAH. (2014). What Child Care Providers and Other Caregivers Should Know. Retrieved from https://cchealth.org/sids/pdf/Child-Care-SIDS-Booklet.pdf.

- Photo provided by the author. ↵

- Office of Head Start. (n.d.). Managing the Classroom: Designing Environments. [public domain]. https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/video/transcripts/design-environments-transc.pdf ↵

- Office of Head Start. (n.d.). Assessing Your Physical Spaces and Strategizing Chances. [public domain]. https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/no-search/iss/managing-the-classroom/design-activities-physical-spaces.pdf ↵

- Office of Head Start. (n.d.). Presenter Notes: Designing Environments. [public domain.] https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/no-search/iss/managing-the-classroom/design-presenter-notes.pdf ↵

- Photo provided by the authour. ↵

- Office of Head Start. (n.d.). Managing the Classroom: Designing Environments. [public domain.] https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/video/transcripts/design-environments-transc.pdf ↵

- Office of Head Start. (n.d.). Preparing for Intentionally Grouping Children. [public domain]. https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/no-search/iss/managing-the-classroom/design-activities-prepare-groups.pdf ↵

- Office of Head Start. (n.d.). Presenter Notes: Designing Environments. [public domain.] https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/no-search/iss/managing-the-classroom/design-presenter-notes.pdf ↵

- Photo provided by author. ↵

- Office of Head Start. (n.d.). Presenter Notes: Designing Environments. [public domain.] https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/no-search/iss/managing-the-classroom/design-presenter-notes.pdf ↵

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2013). AIAN Education Manager Webinar Series: February 2013. [public domain]. https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/video/transcripts/transcript-supporting-children-webinar.pdf ↵

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2023). Biting: A Fact Sheet for Families. [public domain].https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/mental-health/article/biting-fact-sheet-families ↵

- [footnote]U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. (n.d.). Which Toy for Which Child. [public domain]. https://www.cpsc.gov/s3fs-public/2_0.pdf ↵

- U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. (n.d.). Think Toy Safety. [public domain] https://www.cpsc.gov/s3fs-public/281%281%29.pdf ↵

- U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. (n.d.). Which Toy for Which Child. [public domain]. https://www.cpsc.gov/s3fs-public/2_0.pdf ↵

- U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. (n.d.). Which Toy for Which Child. [public domain]. https://www.cpsc.gov/s3fs-public/2_0.pdf ↵

- U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. (n.d.). Think Toy Safety. [public domain] https://www.cpsc.gov/s3fs-public/281%281%29.pdf ↵

- U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. (n.d.). Think Toy Safety. [public domain] https://www.cpsc.gov/s3fs-public/281%281%29.pdf ↵

- U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. (n.d.). Think Toy Safety. [public domain] https://www.cpsc.gov/s3fs-public/281%281%29.pdf ↵

- U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. (n.d.). Think Toy Safety. [public domain] https://www.cpsc.gov/s3fs-public/281%281%29.pdf ↵

- U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. (n.d.). Think Toy Safety. [public domain] https://www.cpsc.gov/s3fs-public/281%281%29.pdf ↵

- U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. (n.d.). Art Materials Business Guide. [public domain]. https://www.cpsc.gov/business--manufacturing/business-education/business-guidance/art-materials ↵

- U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. (n.d.). Art and Craft Safety Guide. [public domain]. https://www.cpsc.gov/s3fs-public/pdfs/blk_media_5015.pdf ↵

- Image by The Art and Creative Materials Institute is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- ACMI. (2020). Home. Retrieved from https://acmiart.org/ ↵

- U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. (n.d.). Art and Craft Safety Guide. [public domain]. https://www.cpsc.gov/s3fs-public/pdfs/blk_media_5015.pdf ↵

- Snell, S. (2018). Don’t Eat the Paint: Art Safety with Young Children. Retrieved from https://communitycarecollege.edu/early-childhood-education/tips-for-art-safety-with-young-children/ ↵

- National Association for the Education of Young Children & Fred Rogers Center for Early Learning and Children’s Media at Saint Vincent College (2012), page 8. (cited in: https://tech.ed.gov/earlylearning/principles/) ↵

- Guernsey, L. (2012) Screen Time: How electronic media—from baby videos to educational software—affects your young child. New York, NY: Basic Books. (cited in: https://tech.ed.gov/earlylearning/principles/) ↵

- Bilingual Pre-K Technology Integration by Professional Learning is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Council on Communications and Media. (2016). Media and Young Minds. Pediatrics, 138 (5). Retrieved from https://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/138/5/e20162591 ↵

- AAP, APHA, & MCHB. (2011). Caring for Our Children: National Health and Safety Performance Standards: Guidelines for Early Care and Educational Programs, Third Edition. Retrieved from https://nrckids.org/files/CFOC3_updated_final.pdf ↵

- California Department of Education. (2015). California Preschool Program Guidelines. ↵

- California Department of Education. (2015). California Preschool Program Guidelines. https://www.cde.ca.gov/sp/cd/re/documents/preschoolproggdlns2015.pdf ↵

- Office of Educational Technology. (n.d.). Guiding Principles for Use of Technology with Early Learners. [public domain].https://tech.ed.gov/earlylearning/principles/ ↵

- U.S. Department of Education, Office of Educational Technology. (2015) Ed tech developer’s guide. Retrieved from https://tech.ed.gov/developers-guide/ (cited in https://tech.ed.gov/earlylearning/principles/) ↵

- Office of Educational Technology. (n.d.). Guiding Principles for Use of Technology with Early Learners. [public domain].https://tech.ed.gov/earlylearning/principles/ ↵

- Office of Educational Technology. (n.d.). Guiding Principles for Use of Technology with Early Learners. [public domain].https://tech.ed.gov/earlylearning/principles/ ↵

- U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. (2011). Small Parts: What Parents Need to Know. [public domain].https://onsafety.cpsc.gov/blog/2011/12/20/small-parts-what-parents-need-to-know/ ↵

- Kimberly McLain, Erin K. O’Hara-Leslie, & Andrea C. Wade. (n.d.). Safety and Injury Prevention. [licensed under CC BY 4.0]. https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-home-health-aide/chapter/safety-and-injury-prevention/ ↵

- Image by r. nial bradshaw is licensed under CC BY 2.0. ↵

- Office of Head Start. (2024). Even Plants Can Be Poisonous. [public domain]. https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/safety-practices/article/even-plants-can-be-poisonous ↵

- Kimberly McLain, Erin K. O’Hara-Leslie, & Andrea C. Wade. (n.d.). Safety and Injury Prevention. [licensed under CC BY 4.0]. https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-home-health-aide/chapter/safety-and-injury-prevention/ ↵

- Kimberly McLain, Erin K. O’Hara-Leslie, & Andrea C. Wade. (n.d.). Safety and Injury Prevention. [licensed under CC BY 4.0]. https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-home-health-aide/chapter/safety-and-injury-prevention/ ↵

- 1st, 2nd, and 3rd degree burns by Bruce Blaus is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0. ↵

- Kimberly McLain, Erin K. O’Hara-Leslie, & Andrea C. Wade. (n.d.). Safety and Injury Prevention. [licensed under CC BY 4.0]. https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-home-health-aide/chapter/safety-and-injury-prevention/ ↵

- Kimberly McLain, Erin K. O’Hara-Leslie, & Andrea C. Wade. (n.d.). Safety and Injury Prevention. [licensed under CC BY 4.0]. https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-home-health-aide/chapter/safety-and-injury-prevention ↵

- Lally, M., Valentine-French, S. (2019). Lifespan Development: A Psychological Perspective. [licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0]. http://dept.clcillinois.edu/psy/LifespanDevelopment.pdf ↵

- Moon, R. Y., Patel, K. M., & Shaefer, S. J. (2000). Sudden infant death syndrome in child care settings. Pediatrics, 106(2 Pt 1), 295–300. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.106.2.295 ↵

- Image by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services is in the public domain. ↵