Chapter 8 – Ethical and Legal Considerations

Previously we discussed the personal attributes that will help you succeed on the job. There are also standards for conducting your professional work ethically and legally that must be understood and heeded. Missteps in these areas will undermine not only your own credibility but can have wide-ranging repercussions for the organization and profession within which you work.

Following is a discussion of the levels of responsibility that affect the information you gather and use, and the messages you create. Once you understand the constraints you must acknowledge in your work as a message creator, you’ll be able to think strategically about the information you need to create that outcome. Having this foundation will also help you evaluate the appropriateness of the information you find.

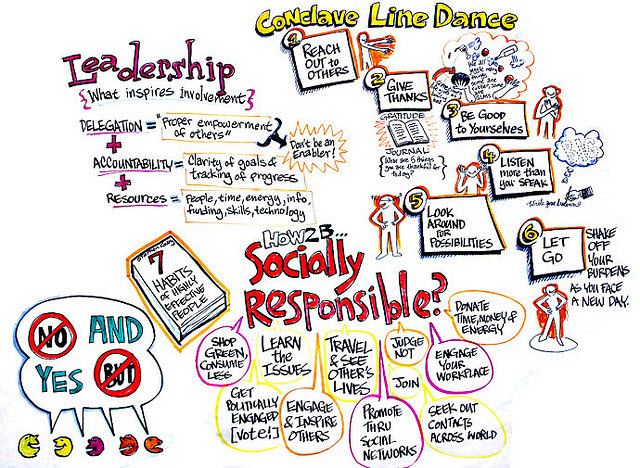

Being a socially responsible communicator requires attention to both ethical standards and legal requirements. First, we need to draw a distinction between ethics and law.

Distinction Between Ethics and Law

Ethics

- A branch of philosophy

- Deals with values relating to human conduct

- Concerned with “rightness” and “wrongness” of actions

- Self-legislated and self-enforced

- Sometimes difficult to determine because of competing, equally-valid possible choices

Law

- Derived from ethical values in a society

- Formally / institutionally determined and enforced through courts and law enforcement officials

- Easily determined because it is a matter of statute and the legality of action and consequences for not adhering to the law is spelled out

In the previous lessons on developing your information task list and determining questions to answer, we’ve focused on specific information-seeking goals. In each of the communication professions, there are key legal considerations that must be understood that will either help or hinder, the seeking of information to meet those goals.

In news, for example, if some of the information needed requires the use of public records then an understanding of public records and privacy laws will help you know what it is possible to get, and how to legally use these records.

In advertising, you might want to make the most of the attributes of the product you are promoting, but you will need to abide by laws dictating the substantiation of product claims.

For public relations professionals, you may need to issue a corporate response to a crisis, therefore it is important to understand the requirements or restrictions of corporate disclosure laws. We will discuss these legal perspectives later in this lesson.

Socially responsible communicators are not content with just staying on the right side of the law. While the law embodies a significant portion of our values, individuals and organizations that want to be considered socially responsible must go beyond the rough requirements of the law itself and adopt higher and more thoughtful standards.

In some cases, these standards may have a legal basis as well as an ethical one. Following these standards requires the communicator to consider both “positive obligations” (things that you must always strive to do) or “negative obligations” (things that you must guard against doing).

Let’s look at the positive and negative obligations that apply to those crafting news messages. These are drawn from the Code of Ethics of the Society of Professional Journalists, a long-standing professional association for news professionals.

Positive Obligations (goals you try always to achieve)

1) Seek truth and report it. This requires that you:

a. test the accuracy of information from all sources.

b. fairly represent multiple perspectives and viewpoints.

c. identify sources whenever feasible so the public may judge the reliability of the information.

d. safeguard the public’s need for information.

Despite the rhetoric of First Amendment attorneys, the public does not have a “right to know” per se. The First Amendment to the Constitution of the United States says that citizens have a right to assemble, speak, practice their chosen religion, petition the government for a redress of grievances, and that the Congress shall make no law limiting the freedom of the press. It does not address the public’s “right to know” anything. But most communication scholars acknowledge the crucial role that the media play in nurturing an informed electorate and citizenry.

2) Minimize harm. This requires that you:

a. avoid privacy violations. Only an overriding public need can justify intrusion into anyone’s privacy and such intrusion may invoke legal sanctions if a source can demonstrate harm. In the context of information seeking, information that can be found should not necessarily be used.

b. be cautious about naming criminals before the formal filing of charges, identifying juvenile suspects or victims, or seeking interviews or photographs of those affected by tragedy or grief.

3) Act independently. This requires that you:

a. be wary of sources offering information for favors or money.

b. disclose potential conflicts of interest. IE: failing to label the content from a video news release in a TV broadcast story is a breach of ethics.

c. hold those with power accountable.

4) Be accountable. This requires that you:

a. admit mistakes and correct them promptly. Libel law may be invoked if the mistake injures a news subject.

b. stand up for what is right in the media organization.

c. abide by the same high standards to which you hold others.

Negative Obligations: (actions that must be avoided)

1) Plagiarism. Never, ever, ever represent someone else’s work as your own. Never. Ever.

2) Concealing conflicts of interest, real or perceived, in seeking or using information. If you have a stake in the outcome of what you are reporting on, you must acknowledge it and perhaps suggest that someone else cover the story.

3) Distorting the content of news photos or video. Image enhancement for technical clarity is permissible, but any other type of manipulation must not happen.

4) Eavesdropping. Listening in on others’ conversations, electronically or otherwise, is a form of information-stealing and may invoke wiretapping laws or other legal sanctions.

5) Breaking the “contract” with a source. Publicly identifying a source who provided information confidentially, for instance, is both an ethical and a legal violation. We will discuss the details of the source contract in lesson 9 on interviewing.

These are a sample of the negative and positive obligations that help you weigh your decisions when a situation arises in your information gathering for a news message.

Ethical thinking requires that you establish for yourself, ahead of time, how you value these various obligations and which take precedence in your own scheme of decision-making. You also must be fully aware of how your media organization has ordered these priorities for their own publications, and comply with the standards that your organization has established.

Just as in news, advertising professionals adhere to a number of constraints when gathering and using information, regardless of the type of advertisement they may be creating. We can once again understand these in the context of positive and negative obligations. These are drawn from the principles and practices of the Institute for Advertising Ethics.

Positive Obligations

1) Create messages with the objective of truth and high ethical standards in serving the public. Advertising is commercial information that must be treated with the same accuracy standards as news and there may be legal repercussions if the standards are not upheld.

2) Apply personal ethics, like being an honest person, in the creation and dissemination of commercial information to consumers.

3) Clearly distinguish advertising from news and editorial content and entertainment, both online and offline.

4) Clearly disclose all material conditions, such as payment or a free product, that affects endorsements in social media and traditional message channels. This is both an ethical and a legal requirement, enforced by the Federal Trade Commission and other regulatory bodies. For example, a blogger who is paid by a company to spread positive information about the company’s product or service must disclose she being paid for her opinions

5) Treat consumers fairly, especially when ads are directed at audiences such as children. In fact, the legal requirements for advertising aimed at children are increasingly stringent.

6) Follow all federal, state and local advertising laws, and cooperate with industry self-regulatory programs for the resolution of complaints.

7) Stand up for what is right within the organization. Members of the team creating ads should express their ethical or legal concerns when they arise. This is a good example of the personal ethics that must factor in decision-making in creating messages.

Negative Obligations

These are obligations that represent both an ethical and, in most cases, a legal/regulatory element. The National Advertising Division of the Council of Better Business Bureaus, the National Advertising Review Board, the Federal Trade Commission, the Federal Food and Drug Administration and many other bodies enforce these obligations when necessary.

1) Do not plagiarize. Never, ever, ever represent someone else’s work as your own.

2) Do not use false or misleading visual or verbal statements.

3) Do not make misleading price claims.

4) Do not make unfair comparisons with a competitive product or service.

5) Do not make insufficiently supported claims.

6) Do not use offensive statements, suggestions or pictures.

7) Do not compromise consumers’ personal privacy, and their choices as to whether to participate in providing personal information should be transparent and easily made.

Let’s look at the positive and negative obligations that help PR specialists gather and use information responsibly. These examples come from the Public Relations Society of America Member Code of Ethics.[1] Once again, many of these obligations refer to both ethical and legal responsibilities.

Positive Obligations

1) Serve the public interest by acting as responsible advocates for those the PR firm or professional represents.

2) Adhere to the highest standards of truth and accuracy while advancing the interests of those the PR firm or professional represents.

3) Acquire and responsibly use specialized knowledge and experience in preparing public relations messages to build mutual understanding, credibility, and relationships among a wide array of institutions and audiences.

4) Provide objective counsel to those the PR firm or professional represents. For example, the best advice for a client may be to admit wrongdoing and apologize. The PR practitioner must objectively weigh this advice and offer it if it is the best option.

5) Deal fairly with clients, employers, competitors, peers, vendors, the media and the general public.

6) Act promptly to correct erroneous communication for which the PR firm or professional is responsible. Again, failure to do this could invoke both ethical and legal sanctions.

Negative Obligations

1) Do not plagiarize. Never, ever, ever represent someone else’s work as your own.

2) Do not give or receive gifts of any type from clients or sources that might influence the information in a message beyond the legal limits and/or in violation of government reporting requirements.

3) Do not violate intellectual property rights in the marketplace. Sharing competitive information, leaking proprietary information, taking confidential information from one employer to another and other such practices are both legal and ethical violations.

4) Do not employ deceptive practices. Asking someone to pose as a “volunteer” to speak at public hearings or participate in a “grass roots” campaign is deceptive, for instance.

5) Avoid conflicts of interest, real or perceived. PR professionals and firms must encourage clients and customers as well as colleagues in the profession to notify all affected parties when a conflict of interest arises.

You can see from the sampling of positive and negative obligations that as a communications professional you must weigh a wide variety of considerations when gathering and using the information to create a message. The intended audience, the purpose of the message, the intent of the communicator, the ethical considerations, the legal constraints, and many other variables help determine how you pursue the information strategy.

As a communications professional you must also conduct your work in the context of a commitment to social responsibility at a number of levels. Because mass communication messages are pervasive and influential, media organizations and professionals are held to high standards for their actions. The social responsibility perspective helps outline how this works.

There are three levels of responsibility that affect your work as a communicator. These are:

- Societal: the relationships between media systems and other major institutions in society.

- Professional / OrganizationalL: your profession’s and your media organization’s own self-regulation and standards for professional conduct.

- Individual: the responsibility you have to society, to your profession, to your audience and to yourself.

We’ll examine each of these in turn.

The societal perspective examines how media institutions interact with other major institutions in society. As a communications professional, it is important to understand the societal implications of your work and the rules under which you operate.

Professional education and licensing have been traditional means by which society has sought to ensure legal and ethical behaviour from those who bear important social responsibilities. For law, medicine, accounting, teaching, architecture, engineering and other fields of expertise, specific training is followed by examinations, state licensing and administration of oaths that include promises to live up to the standards established for the profession.

However, there is no U.S. law that requires communicators to be licensed. Without the power to control entry into the field and withdraw the license to operate as in these other professions, it is even more important for mass communication professionals to police themselves. Especially in light of the huge explosion of “fake news” being generated by individuals with political, cultural or financial motives, legitimate news professionals must defend their crucial role in society.

Let’s look at examples of the way the media interact with other major social institutions. One of the major tenets of journalism is the goal of exposing public officials or business executives to public scrutiny. This “watchdog” role, one of the most important functions of the press, is used to justify journalists’ behaviour in investigating what public officials or corporate executives are doing and whether or not they are meeting their responsibilities to constituents, citizens or shareholders. The First Amendment protects journalists’ rights to challenge government power.

However, serious observers argue that when overly aggressive investigative techniques expose individual politicians or corporate executives to scrutiny about their private lives that may have nothing to do with the performance of their official duties, it causes cynicism, it undermines public confidence in major social institutions, and it drives people away from participation in public and civic engagement. How far does the “watchdog” role go? When is a journalist crossing the line from examining public behaviour to voyeurism about private lives?

Similarly, strategic communications professionals face questions about their interactions with other major social institutions. There is more and more agitation for government regulation of advertising because people perceive that advertisers do not police themselves enough.

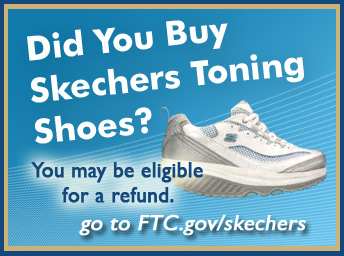

In 2012, the Federal Trade Commission imposed the largest fine in its history on the company that manufactures Skechers athletic shoes and apparel. The company paid $40 million because its ads falsely represented clinical studies backing up claims that Shape-Ups, Resistance Runner, Toners, and Tone-Ups would help people lose weight, and strengthen and tone their gluteal, leg and abdominal muscles. The ads used lines such as “Shape up while you walk,” and “Get in shape without setting foot in a gym.” As part of the settlement, Skechers had to take down the advertising and inform retailers to remove the deceptive claims. It also agreed to stop misrepresenting any tests, studies, or research results regarding toning shoes. And customers who purchased the shoes or apparel were able to file through the FTC for a refund from the company.[2]

The example points out the interactions between advertisers, government regulators and the public at the societal level.

Another example points out the social responsibility interactions between advertisers, corporations and the customers they serve around the sensitive issue of personal privacy.

The social network Facebook, used by 900 million people worldwide, agreed in June 2012 to pay $20 million to settle a lawsuit in California that claimed Facebook publicized that some of its users had “liked” certain advertisers but didn’t pay the users, or give them a way to opt-out.

The so-called “Sponsored Story” feature on Facebook was essentially an advertisement that appeared on the site and included a member’s Facebook page and generally consisted of another friend’s name, profile picture and a statement that the person “likes” that advertiser. The suit was one in a long list of complaints against the social media giant and other online organizations such as Google that appear to be working with advertisers to intrude on consumers’ privacy.[3]

A group of digital advertising trade organizations called the Digital Advertising Alliance is concerned enough about advertisers’ interaction with consumers, technology companies,

privacy advocates and federal/state regulators that it has created a way for people to opt out of having their online behaviour tracked. A turquoise triangle that appears in the upper right-hand corner of banner ads on web sites allows users who click on it to remove themselves from having personalized advertising directed at them.

The group created the option in reaction to pressure from other institutions, including the Federal Trade Commission, which is threatening to regulate mobile and digital privacy and exert more control over children’s privacy online. The example points out how various societal-level institutions interact to impose social responsibility on media practitioners if they do not regulate themselves.

As strategic communicators have adopted social media platforms to distribute their messages, scrutiny by other societal institutions has increased. The Federal Trade Commission was so concerned about claims being made by advertisers and PR practitioners via social media that they updated their social media guidelines in 2013.

The new FTC guidelines require social media marketers to:

- fully disclose their sponsorship of the information. If an advertiser has hired a blogger to endorse a product or service, the blogger MUST disclose that he or she is working for that advertiser; if a PR firm posts positive comments about its clients on social media, the firm MUST disclose that they are working on behalf of the client. Further, the disclosure must be clear and conspicuous; it cannot be buried in the fine print.

- monitor the social media conversation and correct misstatements or problematic claims by commenters.

- create social media policies to instruct employees about the expectations and practices that will be enforced.

The mention of company-specific social media policies leads us to the next category of responsibility: the professional or organizational perspective.

In addition to the societal level of interactions, communication organizations and professionals engage in self-criticism and set standards for their own conduct and performance as information gatherers. One of the most conspicuous examples of this lies in the proliferation of codes of conduct for mass communication activities at all levels. As our discussion of positive and negative obligations (above) demonstrated, every mass communication industry develops these professional and organizational guidelines for its practitioners.

In the news industries, codes have expanded in number and scope over several decades. Organizations that have adopted such codes include the American Society of News Editors, the Society of Professional Journalists, the Associated Press Managing Editors Association, the Radio Television Digital News Association, and the National Press Photographers Association. Individual news organizations and publications frequently establish their own codes to which they expect their staff to adhere.

Advertising codes reflect some of the specific criticism directed at the field, such as charges of deceptive advertising, unfair stereotyping, false testimonials, and misleading claims. Organizations as diverse as the Word-of-Mouth Marketing Association, the Children’s Food and Beverage Advertising Initiative, the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America and the Beer Institute have guidelines and codes for the content and placement of advertisements in their respective industries or for the audiences with which they are concerned.

For instance, here is a portion of the Advertising and Marketing Code for the Beer Institute. Any advertising professional working with a client who sells and advertises beer would need to adhere to this industry code.

“Brewers should employ the perspective of the reasonable adult consumer of legal drinking age in advertising and marketing their products, and should be guided by the following basic principles, which have long been reflected in the policies of the brewing industry and continue to underlie this Code:

- Beer advertising should not suggest directly or indirectly that any of the laws applicable to the sale and consumption of beer should not be complied with.

- Brewers should adhere to contemporary standards of good taste applicable to all commercial advertising and consistent with the medium or context in which the advertising appears.

- Advertising themes, creative aspects, and placements should reflect the fact that Brewers are responsible corporate citizens.

- Brewers strongly oppose abuse or inappropriate consumption of their products.”[4]

Individual advertising agencies and corporate advertising departments also have codes and standards to help employees recognize and deal with ethical questions.

Most media outlets accept or reject ads submitted to them using a set of guidelines about what types of ads are acceptable and what type of content they will allow.

For example, here is a portion of the policy for acceptance of advertising that appears in Texas Parks and Wildlife Magazine

- All advertisements are subject to the approval of the Texas Parks & Wildlife Department (Publisher), which reserves the right to reject or cancel any ad at any time if the ad does not conform to the editorial or graphic standards of the magazine as determined by the Publisher.

- Advertisements that are not appropriate for viewing by youth will not be accepted. Advertisements will not be accepted for tobacco or alcohol products. (Tex. Parks & Wild. Code §11.172(c); 31 Tex. Admin. Code §51.72. Other products that are not compatible with the mission of the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department will also not be accepted.

- Advertisers must keep in mind the diverse audience of the magazine when determining the suitability of an ad. That audience includes hunters, anglers, campers, bird watchers, state parks visitors, other outdoor enthusiasts and readers of all ages including children.[5]

Any advertising professional gathering information and creating an ad for a product or service that might appear in this magazine would need to be aware of the publication’s organizational level guidelines about acceptable advertising, and the societal level regulations (Texas state laws) about tobacco or alcohol advertising in this publication.

Public relations practitioners, like advertising specialists, work closely with clients. Through these associations, legal and ethical decisions often arise as clients and publicists discuss information-gathering strategies. For example, the Securities and Exchange Commission monitors the way corporations report their financial affairs, scrutinizing information about stock offerings and financial balance sheets for accuracy and omission of important facts. Their objective is to ensure that investors and stock analysts can get accurate information about the companies that are offering securities.

Increasingly, legal and ethical standards are holding public relations practitioners, along with stockbrokers, lawyers, and accountants responsible for the accuracy of the information they communicate to the public. When public relations professionals find themselves on the losing side of an important ethical question with a client, it is not unusual for them to resign their positions as a matter of principle.

The Public Relations Society of America’s Code of Ethics[6] emphasizes honesty and accountability, in addition to expertise, advocacy, fairness, independence, and loyalty. The public relations code, like those for advertising and journalism, reflects the concerns of society as well as the practitioners who adopt the codes. Provisions of all the codes are designed, at least in part, to provide the public with reasons to have confidence in communicators’ integrity and in the messages they create. Of course, the codes are also there to help keep communicators out of court.

For example, a large multinational PR firm resigned its account with a major tire manufacturer just months after landing the account. The reason was that the tire manufacturer failed to disclose to the PR firm that it knew about defects in its tires that had caused a number of fatal accidents. The PR professionals decided they could not ethically represent the tire manufacturer to the public under such circumstances and ended their relationship with the company. The PR firm’s adherence to professional and organizational standards was more important than the income that would have been generated from the account with the tire manufacturer.[7]

There is an individual level of responsibility for your own behaviour. As a communications professional, you may find yourself confronting conflicting obligations in your daily routine. You will be doing your work in a decidedly ambivalent atmosphere. News professionals are criticized for reinforcing the assumptions of those in power and ignoring reality as experienced by most of the population. Advertising is criticized for contributing to materialism, wasteful consumption, and the corruption of the electoral system. Public relations is criticized for creating and manipulating images on behalf of those with narrow interests, failing to give public interest information a priority.

In confronting your social responsibility using the individual perspective, you are likely to place duty to yourself at the top of the list. You always need to abide by your own moral standards. But this may conflict with more worldly ambitions – the desire for recognition, advancement, and financial security. The duty to the organization may be at odds with the loyalty to colleagues or to the profession. Let’s look at a few examples that illustrate these tensions.

Am I Comfortable Working on Advertising for This Client?

Individual-level responsibility may arise when ad professionals object to ads they have to work on or have to accept. It is usually not necessary to violate your own standards.

Concerns about taking on an assignment will be something to discuss during the message clarification step. If, for example, you are a strict vegetarian, it may be difficult for you to work on a campaign to sell bacon.

Or let’s say that you are the advertising manager for a local magazine. You receive an ad that you think is offensive, even though the product or service being advertised is perfectly legal and the company is a big advertiser in your publication.

You don’t have to accept that offensive ad, but you also don’t have to forgo the ad revenue for your publication (again, we’re weighing two competing obligations—your obligation to your own standards against your obligation to your media organization to generate revenue).

The way to resolve this dilemma is to call the ad agency and ask for another version of the advertisement. Advertisers almost always have another version in anticipation that some media outlets will refuse to run a potentially-offensive version of an ad. With this solution, you can adhere to your own standards and still generate revenue for your publication by accepting the more appropriate ad.

There are entire texts and semester-long courses that examine the specific laws and regulations under which mass communicators operate. We will discuss here briefly a few of the most relevant types of legal and regulatory constraints that affect communicators’ gathering and use of information in messages in this lesson. We will return to some of these examples in more depth throughout the rest of the lessons where appropriate.

Journalism Law and Regulation

You will learn about the relevant legal and regulatory framework for your career as a journalist in later classes. We will mention just a couple of examples that demonstrate the way that laws and regulations affect journalists’ information strategy process.

Federal, state and local law outlines the way journalists gather information. For example, photographers/videographers have a constitutional right to photograph anything that is in plain view when they are lawfully in a public space. Police officers may not confiscate or demand to view journalists’ photographs or videos without a warrant. However, the right to photograph does NOT give journalists the right to break other laws. For example, you may not trespass on private property to capture an image.

Likewise, there are a wide variety of laws that detail the types of information that are accessible to the public, including journalists. Public records laws will be discussed in more detail in Lesson 13. Suffice it to say that journalists have many tools in their toolbelt when they are seeking access to public record information.

Libel law defines the ways that journalists USE the information they gather in their messages. Again, there are many nuances in libel law and journalists generally defer to the experts within their media organizations when questions arise about whether a particular item in a news story exposes the news organization to a charge of libel. It is most important for you, as an information gatherer, to understand that best practices require you to double- and triple-check any facts, claims or evidence you intend to use in a message and to vet that information with the appropriate gatekeepers in your organization.

The advertising substantiation rule is of paramount importance for anyone collecting and evaluating information to use in a comparison ad. The advertiser must be able to substantiate any claim about a product or service with information that backs up such claims. This means that you, as the advertising professional, will follow a comprehensive information strategy in preparing the background information for any such ad.

The main governmental regulatory agency for advertising is the Federal Trade Commission. The FTC regulates unfair and deceptive practices on a case-by-case basis and occasionally with industry-wide regulations.

The FTC has the power to require that advertisers prove their claims. If the FTC determines that an advertisement is deceptive, it can stop the ad and order the sponsor to issue corrections. Corrective advertising provides information that was omitted from a deceptive ad. Some companies are fined for their illegal acts. It is extremely rare, but someone could also be jailed for a deception.

Many states also have laws that regulate deceptive advertising. Individual consumers also have the right to sue companies for deceptive advertising.

The advertising industry also has a two-tiered self-regulatory mechanism. Advertising that is charged with being deceptive can be referred to as the National Advertising Division (NAD) of the Council of Better Business Bureaus. For cases that are not satisfactorily resolved through NAD, appeals can be made to the National Advertising Review Board. The Board can put pressure on advertisers through persuasion, publicity or even legal action if it is deemed necessary.

Public relations firms increasingly are investigated along with the corporations they represent in situations of litigation, disputes about investor relations, etc. In fact, after a number of highly publicized cases of major corporate financial malfeasance came to light, public relations departments and firms reviewed their own roles in unwittingly misleading the public about the financial health of organizations that were in deep trouble. In another example, athletic apparel giant Nike was taken to court by a workers’ safety advocate because it released press statements defending its reputation against charges of mistreating overseas workers. The news releases were said to represent false advertising. The case served as a wake-up call to public relations firms that send out press releases every day.[8]

In a relatively new twist, a number of “guerilla marketing” firms tout their ability to generate “buzz” about products and services on web sites populated by teens. The firms were recruiting young people with promises of gifts and access to the newest gadgets. In exchange, the teens agreed to go online to popular social networking sites and sing the praises of the products they had received and encourage their peers to buy the merchandise, all without disclosing that they were actually working for a marketing firm.

These practices raised ethical questions about the truthfulness of messages that fail to disclose conflicts of interest (one of the negative obligations mentioned earlier). When confronted with ethical concerns, many of the marketing and promotion firms claimed that if someone asked, their operatives were instructed to say that they were working for the movie studio, the gadget company or the bubble gum producer. But how many audience members, especially younger ones, were likely to ask?

As we’ve said, the Federal Trade Commission has now ruled that “word-of-mouth” endorsers of products or services (such as those who post positive messages on social networking sites, etc.) must disclose that they are being compensated with money or free goods and services as part of their posts to these sites. Guidelines originally issued by the Food and Drug Administration regarding direct-to-consumer pharmaceutical advertising now include similar advice for any person or company making claims about medical, food or cosmetic products through social media.

All of these levels of responsibility influence how communicators weigh their actions and make their decisions. Societal expectations, organizational and professional routines and norms, and individual standards are going to play a role in each decision you are faced with making. As long as you have a systematic method for evaluating each situation and for applying your professional standards, you should be able to make your information decisions in an ethical and defensible manner.

The information strategy provides you with the skills to ensure that you don’t have to resort to inappropriate, unethical, or illegal means to gather information. If one method of gathering information seems inappropriate, your skill with a well-developed information strategy means you can use another, more appropriate, method to find what you need. Being a highly skilled information gatherer in an information-overloaded society brings credibility to you and to your organization.

Further, using an explicit information strategy helps you explain your standards to others. When the public, colleagues, or supervisors challenge the information on which you base a message, you can present an ordered, rational account of your information search and selection process. Using the standards and methods available in the information strategy allows others to evaluate your skill and expertise as a communications professional.

RESOURCES

A collection of news organizations’ ethics codes can be found at The Center for Journalism Ethics’ Ethics Resources page.

- Public Relations Society of America. (n.d.). Public Relations Society of America Member Code of Ethics. https://www.prsa.org/about/prsa-code-of-ethics ↵

- Bachman, K. (2012, May 16). Skechers Settles Deceptive Ad Case with FTC for $40M. AdWeek, at http://www.adweek.com/news/advertising-branding/skechers-settles-deceptive-ad-case-ftc-40m-140577 captured on July 26, 2012. ↵

- Levine, D. and McBride, S. (2012, June 18). Facebook ‘Sponsored Stories’ Lawsuit: Company to Pay $10 Million Settlement. HuffPost Tech Blog at http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2012/06/16/facebook-sponsored-stories-lawsuit-10-million_n_1602905.html, captured on July 26, 2012. ↵

- Beer Institute Advertising and Marketing Code, at https://www.beerinstitute.org/responsibility/advertising-marketing-code/, captured on August 15, 2017. ↵

- Magazine Advertising Policy, Texas Parks & Wildlife magazine, at http://www.tpwmagazine.com/advertising/policy/, captured on July 26, 2015. ↵

- The Public Relations Society of America’s Code of Ethics. https://www.prsa.org/about/prsa-code-of-ethics ↵

- Miller, K. (2000, September 7). Firestone’s PR Firm Resigns, Washington Post at http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/aponline/20000907/aponline231008_000.htm, captured on July 26, 2012. ↵

- Egelko, B. (2003, September 13) Nike settles suit for $1.5 million, San Francisco Chronicle at http://www.sfgate.com/default/article/Nike-settles-suit-for-1-5-million-Shoe-giant-2589523.php, captured on July 26, 2012. ↵