Chapter 7 – Public Relations Writing Basics

Information Strategy Process and the Needs of Communicators

Information for Messages

Communicators perform two basic tasks: they gather and evaluate information, and they create messages. This course focuses on the information strategy skills communicators must hone to find the information they need to form effective messages.

Media messages take myriad forms and serve different functions. In this lesson, we will discuss the variety of media message types.

To get started, answer this – which of the following is not a media message?

- Editorial about mass transit needs

- Branded content (advertorial) about nursing home services

- News release announcing a company’s merger with another company

- TV commercial for dog food

- Breaking news story about a tornado

- Profile of a performance artist

- Billboard for a mobile phone company

- Five-part series on climate change

- Pop-up ad on your mobile device for cheap car insurance

- Reporter’s Twitter post linking to a new investigative report

The answer, of course, is that they all are media messages.

The differences in these messages, though, are readily apparent. Where you find them, what purpose they serve, and what the message creator hopes you will do with the information contained in the message are all different. So are the information requirements in creating these different messages. The pop-up ad just needs the facts about the insurance company and a link, whereas the series on global warming needs extensive information from reports and experts to effectively create the message.

Whether you are a reporter, a public relations specialist, or someone who works in advertising, the main output of your work will be a media message.

According to Wikipedia, “A message in its most general meaning is an object of communication. It is a vessel which provides information.” Just as it takes clay to make pottery, it takes information to craft a message. At all stages in the process of crafting a message, information is the essential material. Just as pottery can come in many shapes and forms and serve various purposes, so, too, do the information “vessels” communicators create.

The Information Strategy Process

These steps, by way of review, are:

- clarify the parameters of the message assignment.

- identify potential audiences.

- generate ideas and bring focus to the topic.

- understand the variety of potential contributors of information.

- appreciate the ethical and legal considerations required.

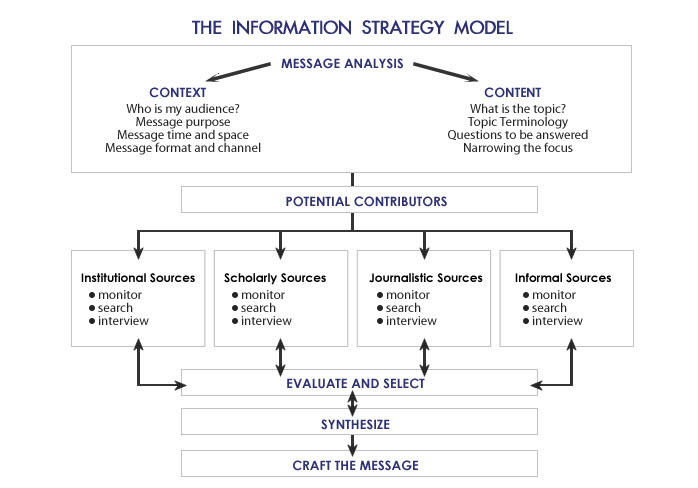

Models can be useful ways to illustrate often complicated processes. The Information Strategy Process model below recognizes that in an information-rich environment, it is impossible to remember thousands of specific information-finding tools and resources for answering specific questions. Instead, the model suggests a systematic course to follow when developing a strategy for determining, and seeking, the information needed for any message type or topic.

The model identifies the steps in the information strategy process and indicates the paths between the steps. As the two-way arrows indicate, the process may include some backtracking in the course of verifying information or raising additional questions. As a graphic representation of both the steps to take in the process and the sources that might meet a particular information need, the model serves as the outline of your entire information-gathering process.

The model also identifies the contributors to an information strategy. Information is created by many different types of sources and is intended to meet a wide variety of needs for both the information creator and for anyone who might gather and use that information. The model points out the major contributors or sources of information: institutional sources (which include both public-sector and private- sector institutions), scholarly sources, journalistic sources, and informal sources.

The information strategy model for mass communicators applies to any type of message task and any topic that you may be working on. The process applies to an information search for news, advertising, public relations or even for an academic paper. The information strategy process can facilitate the search for information on any topic and for any audience.

For mass communicators, the information strategy process will help you:

- think through the message’s purpose, context, audience, and key topics

- identify and select a manageable portion of the topic which needs to be examined

- develop a method for an in-depth examination of a segment of the topic selected

- identify appropriate potential sources of information

- select effective techniques for researching the topic

- determine a vocabulary for discussing your message analysis, information gathering and selection process with others (colleagues, supervisors, critics, audience members. etc.)

- save time by helping you avoid wading through masses of information that may be interesting, but in the end, not very useful for the message task

We will use this conceptual map as a way to think about how to accomplish each of the information tasks that communication professionals might face.

Information Tasks of Communication Professionals

Each of the mass communication professions – journalism, advertising, public relations – serve different information objectives for their organizations.

Journalistic organizations want to inform and engage the readers / viewers / listeners of their messages through publishing stories about current events, people, ideas, or useful tips. By providing compelling and interesting information they hope to draw an audience to the publications in which their messages appear.

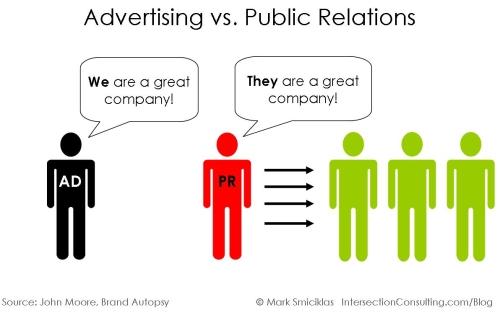

Advertising firms create messages for their clients that inform or persuade potential customers to purchase a product or service or adopt an idea or perspective. Ads generally include a “call to action” that identifies the intended outcome of the message.

Public relations firms help their clients influence legislators, stakeholders (ie: regulators, business partners, media organizations and the general public) to think positively about the company or organization and manage the organization’s information environment.

They serve these key objectives using a variety of message types. Let’s look at the different forms of media messages in news organizations, advertising agencies, and public relations firms and the information tasks of the professionals creating those messages.

News Messages

News messages are often broken into three categories: “hard” news, “soft” news or features, and opinion. “Hard” news comprises reports of important issues, current events, and other topics that inform citizens about what is going on in the world and their communities while “soft” news covers those things that are not necessarily important and are handled with a lighter approach. Opinion pieces, unlike the other two which value “objectivity,” are subjective and will have a specific point of view.

Hard News

Breaking news – Sometimes referred to as “the first take on history” breaking news stories provide as clear and accurate an accounting of some kind of event as possible while it is happening. In reporting about wildfires raging in the west, the breaking news story requires a timely accounting of what’s happening, with a tight focus on the “who, what, when, where, why” and it requires well-honed observation and interviewing skills. For the breaking news story, the information tasks for the reporters are to show up, assess the situation, use their senses to cover the event and learn more information through first-person interviews. Breaking news provides the “need to know” information as an event unfolds.

Depth report – The depth report is the story after the breaking news report. The goals for journalists preparing a depth report are to try to help people understand how the event happened, who was affected, what is being done about it, how people are reacting. For instance, in the aftermath of a story about wildfires in the West, the reporter’s information tasks would include gathering background information about the firefighting efforts, the economic impact of the fires, the reactions of home and business owners, the potential impact that the weather might have on future similar events. As with the breaking news story, the journalist is transmitting information, not opinion and they must be able to identify the most knowledgeable sources.

Analysis or interpretive report – The focus here is on an issue, problem or controversy. The substance of the report is still a verifiable fact, not opinion. But instead of presenting facts as with breaking news or a depth report and hoping the facts speak for themselves, the reporter writing an interpretive piece clarifies, explains, analyzes. The report usually focuses on WHY something has (or has not) happened. The information tasks are greater for this type of report, due to the need to clarify and explain rather than simply narrate. An analysis of the wildfires might look into how environmental policy or urban sprawl factored into the event. Analyses generally require learning about different perspectives or ranges of opinion from a variety of experts and more “digging” into causes.

Investigative report – Unlike the analysis which follows up on a news event, the information tasks for an investigative report require journalists to uncover information that will not be handed to them, these stories are reported by opening closed doors and closed mouths. These are the stories that expose problems or controversies authorities may not want to see covered. This requires unearthing hidden or previously unorganized information in order to clarify, explain and analyze something. A key technique used in investigative reports is data analysis. In the aftermath of the wildfires, a news organization might investigate the insurance claims process or how a charitable organization that received relief funds for fire victims actually allocated the money. The investigative report requires the communicator to have a high level of information sophistication, and the ability to convey complex information in a straightforward way for the audience.

Soft News

Feature – The feature differs from the other types of news reports in intent. The previous examples seek to inform the audience about something of importance or concern. Features, on the other hand, are designed to capture audience interest and are more about providing entertainment than critical information. The feature story depends on the style, great writing, and humor as much as on the information it contains. There are several types of features:

News – A story about a man who used cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) to revive a pet dog rescued from the bottom of a pool might be reported as a news feature. It is based on an event, but covered as a feature, but the information tasks require gathering material to put more emphasis on the drama of the event than on the information about how to do CPR on a dog.

Personality sketch or profile – A story about the accomplishments, attitudes and characteristics of an individual seeks to capture the essence of a person. This requires both thorough backgrounding of the subject and skills in interviewing as information tasks. The communicator has to have a well-honed ability for noticing details that bring to life what is interesting or unique about the person.

Informative – A sidebar to accompany a main news story might be written as an informative feature. For example, an informative feature that describes the various methods firefighters use to combat wildfires might accompany a breaking news story. The information tasks for the reporter include a good command of sometimes-technical information to convey the story to the audience.

Historical – Holidays are often the inspiration for this type of piece, with focus on the history of the Christmas tree, the first Thanksgiving dinner, etc. The curious communicator could also create features about the anniversary of the founding of an important local business or the celebration of statehood using background archival documents. The information tasks for these types of reports obviously require locating and interpreting extensive historical information.

Descriptive – Many features are about places people can visit, or events they can attend. Tourist spots, historical sites, recreational areas, and festivals all generate reams of feature story copy, pictures and video. Public relations specialists often have a significant hand in generating much of the background information in these types of features and promoting these events or places to the news media. The information tasks include finding a fresh and engaging angle for the content.

How-to – Some features are created to provide information about how to improve your golf game, become a power-shopper, install your own shower tile. The communicator has to have a solid grasp of the subject matter to do a respectable job with this type of piece. The information tasks for how-to features include the need for material that is descriptive, specific, and very clearly communicated.

Opinion:

These types of reports include editorials, columns, and reviews. They are characterized by the presentation of facts and opinion to entertain and influence the audience. Nonetheless, they still require correlation and analysis of information. Because their purpose is persuasion, they must contain clear, detailed information and make logical and understandable arguments in support of the point of view being presented.

Editorials – The editorial is a reflection of management’s attitude rather than a reporter’s or editor’s personal view. Most are unsigned and run on a specific page of the newspaper or website or during a particular time of the broadcast. Editorials usually seek to do one of three things: commend or condemn some action; persuade the audience to some point of view; or entertain and amuse the audience. The information tasks for an editorial include locating and using credible information as evidence for whatever position is being taken.

Reviews – Reviewers make informed judgments about the content and quality of something presented to the public–books, films, theater, television programs, concerts, recorded music, art exhibits, restaurants. The responsibility of reviewers is to report and evaluate on behalf of the audience. The information must be descriptive as well as evaluative. The reviewer describes the concert and then makes an evaluation of the quality of the performance. Reviewers’ information tasks require them to be deeply knowledgeable about the type of content or activity they are reviewing, as well as having an opinion about it.

Advertising Messages

Advertising is defined as a paid form of communication from an identified sponsor using mass media to persuade or influence an audience. Because there are so many diverse advertisers attempting to reach so many different types of audiences with persuasive messages, many forms of advertising have developed. We will discuss nine types of advertising and the information tasks they require of the communicator.

1) Brand or national consumer advertising – This type of advertising emphasizes brand identity and image. Advertising campaigns for Coca-Cola, Nike, or American Express are examples. Brand advertising seeks to generate demand for a product or service, and then convince the audience that a specific brand is the one they want. For example, Nike ads seek to generate demand for expensive athletic shoes and to convince purchasers that they want Nikes rather than Reeboks. The information tasks for these types of campaigns are extensive but much of the information that is gathered usually does not actually appear in the content of the ads themselves. Rather, the information informs the development of the advertising campaign strategy and the choice of media in which to place the ads.

2) Retail – Advertising that is local and that focuses on the store where products and services can be purchased is called retail advertising. The message emphasizes price, availability, location and hours of operation. Nike, for example, might generate a brand ad about their shoes, but the local department store would generate a retail ad telling about the great sale they are having on Nikes and other shoes. The department store managers don’t care which brand of shoe you buy as long as you shop in their store rather than their competitor’s store. The information tasks for these types of ads include gathering a lot of highly specific information about the retailer, given the purpose of the advertisements.

3) Directory – Ads that help you learn where to buy a product or service are directory ads. The telephone yellow pages are the most common form of directory ads, but many other directories perform the same function. The ads that appear as “sponsored links” next to your results from a search in a search engine are a form of directory ads. They are classified and served to you according to the terms in your search. These types of ads are almost purely information-based and meet an already-expressed need for information on the part of the audience member. The information tasks connected to directory ads include analysis of vast data sets of information about consumers, much of which is done by computer algorithms. But the ad creators need to understand how and why a particular consumer was targeted for a particular ad in order to be effective.

4) Political – Ads designed to persuade people to vote for a politician are familiar fixtures on the media landscape every political season. We can all recall candidate ads we’ve seen during each election cycle. Information tasks for this type of ad include gathering background research about the opposition candidate as well as material about the candidate sponsoring the ad, the latest polls of likely voters, public attitudes about the issues, and other facts that inform the strategy for the copy and placement of the ad. Communicators also must know the relevant legal and regulatory restrictions for political advertising in each market where the ads may run.

5) Direct-response – These types of ads can appear in any medium. A direct-response ad tries to stimulate a sale directly. The consumer can respond by phone, mail, or electronically, and the product is delivered directly to the consumer by mail or to a mobile device (a coupon for the pizza parlor you just passed on the street). On television, the infomercials for hair-care products, exercise equipment, or kitchen gear are examples of direct-response ads. Flyers you get in the mail to “Buy this Product” are also examples. These ads have a high information component and the communicators’ information tasks reflect the need to be well-informed. The message-makers assume the audience is already interested in or curious about the goods or services since they are watching the infomercial, reading the catalog, or have gone to the website. The direct-response piece includes lots of information about the products, and the goal is to make the sale. Mobile versions of direct response ads have to have a good “hook” to get the receiver to pay attention and act.

6) Business-to-business – Messages directed at retailers, wholesalers, distributors, industrial purchasers, and professionals such as lawyers and physicians comprise business-to-business advertising. These ads are concentrated in business and professional publications. For example, banks advertise to small business owners; or equipment manufacturers advertise to factory managers, hospital administrators, restaurant owners, and others who might purchase their equipment. Unless you do the type of work that makes you an audience member for these kinds of messages, you aren’t likely to see very many business-to-business ads. Because these types of ads require that they are directed toward a specialist audience with specific needs for products or services tailored for a particular industry, the information tasks required to produce these ads are highly detailed.

7) Institutional – This form of advertising is sometimes called corporate advertising. The focus of the message is on establishing a corporate identity or winning the public over to the organization’s point of view. Rather than outlining the product or service offered by the institution, the ad attempts to create an image or reinforce an attitude about the company as a whole. Also, the ad may attempt to influence policymaking by advocating a particular position on some national issue that affects the interests of the sponsoring institution. The information component of this type of ad usually consists of extensive background research about the attitudes and psychologies of the intended audience, and the information tasks include gathering in-depth knowledge about the sponsoring institution and its goals for the message.

8) Advertising features – Also referred to as an advertorial, branded content or native ads, this form is

becoming more common. Many magazines carry inserts that look like a feature piece but are actually generated by an advertiser or a public relations firm, not by a journalist. For example, you might find an insert in a newsweekly magazine about living a healthy lifestyle, with articles and photographs that are sponsored by a pharmaceutical company. The communicator must have solid background information about the product, service or topic AND must know how to write like a journalist. Hence, the information tasks for this type of content include both content and stylistic aspects.

9) Public service – This type of ad communicates a message on behalf of some good cause, such as stopping drunk driving or preventing AIDS. Unlike the other types of advertising, media professionals create these ads for free, and time or space to run the ads are donated by media outlets. The ads typically include some information that emphasizes the nature of the problem or the cause so as to induce the audience to take the problem seriously. Information tasks for public service ads or PSAs usually includes identifying an emotional or psychological “hook” for the audience to get engaged with the ad content. Watch the YouTube video UNEP World Environment Day PSA, created for World Environment Day 2014.

Much of the information that is used in the creation of advertising never actually appears in the copy of the ad or in the visuals that are produced. Instead, extensive information is uncovered to help the advertising professionals understand the background of the audience and message. For instance, communicators need to understand the product or service they will be pitching, the interests and needs of the intended audience, the competitors’ product advantages and disadvantages, all of which help them decide how much money should be spent on the campaign and where the ads should appear.

Public Relations Messages

Public relations messages are sometimes referred to as “earned media” (as opposed to “paid media” like advertising.) This means that the PR professional has “earned” the attention of the journalist who decides to use the information the PR professional supplied as the germ of a news story. The messages created by public relations professionals get a major portion of their exposure through journalism organizations – output from public relations professionals is a major source of news. A significant routine for news professionals is the monitoring and use of news releases generated by public relations specialists, attendance at news conferences organized by PR professionals, coverage of events sponsored by PR strategists, and use of material from the media kits that PR firms create for their clients.

Generally speaking, the policy of news organizations is that PR-generated messages are checked, edited, and supplemented by information independently generated by news professionals before running. In fact, much PR appears in mass media, but most of it is produced for specialized media such as trade, association, and employee publications. Public relations messages are also a part of what is referred to as “strategic communications” along with advertising in that there is a strategic objective in the crafting of the message to influence people’s opinions or purchasing decisions.

Just as there are various forms of news and advertising messages, there are a number of forms of public relations messages, and a set of information tasks for communicators.

1) Internal PR – These include corporate newsletters, crisis management plans, corporate intelligence reports, and other forms of communication that are intended for the internal audience of employees and officers of a company. Also included here are the annual reports prepared for stockholders in publicly-held firms. These types of public relations media are information-rich and the information tasks include having an extensive understanding of the company, the issues and problems the company faces, the finances of the firm and any other factors that employees and stockholders would have an interest in knowing about.

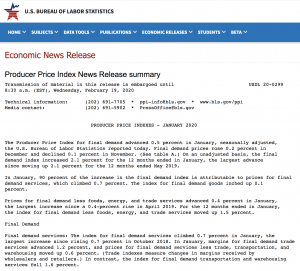

2) News releases – News releases are sent to media outlets by PR specialists who want to generate interest for their client or company. A news release might be prepared:

- as a simple announcement story (IBM’s 3rd quarter profits rose)

- as an advance story (The circus will be unloading animals for the 3-day stay in town at such-and-such a place and time)

- as a follow-up after an event (Ground was broken for a new nursing home)

- in response to a trend, current event or unfolding crisis (Interest rates are at an all-time low, so ABC Mortgage is offering the following tips to consumers about refinancing).

The best news releases are produced to have the look and feel of a news story that might have been produced by news professionals. They, therefore, share many of the same information characteristics as news reports. The one big difference, as we have already stated, is that PR specialists are not obligated to tell all sides of the story. The information tasks for news release producers are very similar to those for feature story journalists.

3) Broadcast (video) news releases – A video news release (VNR) is simply a news release in the form of a broadcast news story. The video and voice-over are designed to look like a piece that you would see on any television news program. B-roll footage, or video images sent to the media, is closely related to a VNR. The difference is that b-roll does not include a narrated voice-over, and is not edited as a ready-to-go news package. Reporters use b-roll footage from companies to enhance their own stories. For example, for a new movie release, the promotion company might send out b-roll footage of the filming to be used in a story or review.

An audio news release (ANR) is designed to be played on the radio. The audio clip might be a “voicer,” a news story recorded by a PR professional in the style of a radio announcer; or the clip might be an “actuality,” the actual voice of a newsmaker or news source speaking. These types of messages are usually accompanied by a print news release or an announcement to alert news professionals that the VNR or ANR is available.

Watch the YouTube video from News Generation for an explanation of Audio News Releases (ANR).

Once again, these announcements are produced to have the look and sound of reports produced by news professionals, but with a different standard for completeness of the information. PR news releases rarely include information representing all sides of the issue. For that reason, it is generally considered an ethical breach to use information from a VNR or ANR without attributing it to the source so the news audience isn’t confused about where the information originated. But the information tasks are again similar to those for feature journalists.

4) Media kits – Media kits consist of a fact sheet about the client or event, biographic sketches of major people involved, a straight news story, news-column material, a news feature, a brochure, photographs, and for those kits delivered digitally, audio and video segments. Often, media professionals package these materials in a folder or other unique format that is professionally designed and printed or post the materials on a website specifically created for the distribution of the media kit content. Public relations organizations create media kits with the intent of providing story ideas for news professionals, as well as to generate interest and attention for the client. For example, the Salvation Army might update its “Kettle Bell Ringing” media kit before the holiday season each year. Magazine publishers create media kits to attract advertisers by highlighting the size and quality of their audiences, the effectiveness of their editorial content and the prices for placing an ad. With all the different components that go into a media kit, you can understand that the information tasks for communicators producing these types of messages are large in number and detailed requirements.

5) Backgrounder or briefing session – PR specialists provide in-depth information about an issue or event for reporters in backgrounders or briefing sessions. The PR people offer handouts (information sheets or reports) and the principal news source about the issue or event makes a presentation. Unlike news conferences, there is little give and take between reporters and the moderator of these sessions. They are used to explain a policy or situation rather than to announce something. The National Transportation and Safety Board (NTSB), for example, might hold a briefing session following an airplane crash. The handouts prepared for these sessions are sometimes quite extensive, requiring solid information preparation among the PR specialists working on the handouts. The information tasks for the PR specialists include the need to anticipate the types of questions journalists will ask and the depth of follow-up material they need to provide.

6) News conferences – There are two categories of news conferences: information or personality. The information news conference usually has a single motive – someone wants media attention for an announcement, for an update on a breaking event, for a follow-up about an investigation, or some other specific item of interest to news professionals. There is give and take as reporters ask questions of the person at the podium.

The personality news conference is designed to provide news professionals with access to someone famous, about-to-be-famous, or otherwise in the public spotlight. Whenever a professional sports team signs a major college star, for example, there is usually a personality news conference where the individual

Information tasks for a news conference include preparing an opening statement, a briefing paper for the person which anticipates reporters’ questions, and social media content that can be shared during and after the news conference. There may also be a handout outlining the major points made in the announcement. Again, PR specialists must understand what makes news and prepare their news conference information to meet those requirements.

7) Media tour – Like a briefing or background session, the purpose of a media tour is to provide in-depth information to reporters. However, the format of the meetings that take place on the media tour is often highly interactive, with one-on-one between a reporter and company official (and public relations specialist). The nature of the information provided as part of a media tour is generally slightly less timely than what would be discussed as part of a news backgrounder or briefing. A media tour might be arranged so that reporters can “demo” a new high-tech product while a company representative walks them through the features. PR specialists’ information tasks include knowing what will be most interesting to the journalists on the tour and what can and can’t be shared as part of the event.

8) Special events – PR specialists may plan special events (sometimes disparagingly-labeled “pseudo-events”) for clients who want media attention for a cause or issue. There may be a jump-rope-a-thon for cancer research, or a grain company may sponsor a food lift for famine victims. These events must be planned to have news value, and the information that is generated to announce and entice coverage by news professionals must have all of the same characteristics that we have already mentioned. Coverage of these types of events is usually framed as a feature, with similar information tasks for PR practitioners.

9) Responses to media inquiries – There are cases when a company may not proactively send out a news release or hold a press conference but may receive requests from the media for comment. Public relations employees are there to respond to reporters’ requests for quotes, examples or explanations. In these cases, the public relations practitioner needs to act quickly to help meet the journalist’s deadline, and the information tasks involve gathering additional background information about the situation and arranging a meeting or conference call with company management to discuss how best to respond. Getting back to a reporter in a timely manner is key to maintaining good relationships with the media, even if the response is that your company will not be able to provide the requested statement or information at that particular time. Keeping the reporter informed is always a better approach than “stonewalling.”

10) PR features – As is the case for advertising message types, many PR firms and corporate communications professionals are creating branded content or native ads. This is sometimes referred to as “owned media” when it is created by the sponsoring company itself. Companies may create entire websites, magazines or video channels specifically for this type of “owned media” content. The communicator must have solid background information about the product, service or topic AND must know how to write like a journalist as part of the information tasks necessary to be successful.

Storytelling and the Information Strategy

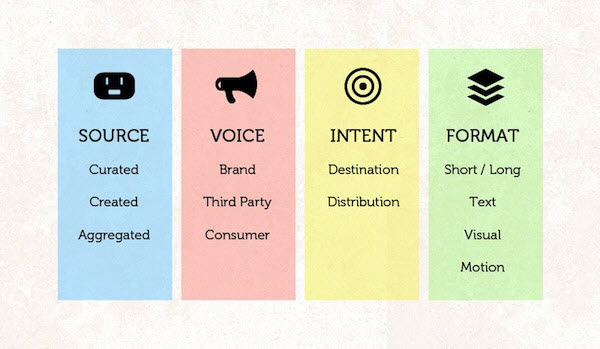

The way information is crafted into the final media message depends on two key factors:

- how the message is being delivered (a story in a newspaper versus on a mobile device, a TV brand ad or one in an interactive magazine)

- the audience for whom the message is intended

The storytelling techniques you use must take into account the media format in which the information is delivered and the audience’s expectations for the message.

While this course does not delve into the actual construction of the messages themselves – you will get those skills in your reporting or strategic writing classes – it is worthwhile to acknowledge some of the considerations that message creators must keep in mind – and the information requirements there might be for different storytelling conventions.

Goals of Storytelling

Storytelling can serve different kinds of goals. Determining the intention or purpose of the story or message is an important first step in crafting the message. As you have learned, messages can inform or enlighten people about current events or issues or about the availability of products or services. They can provide background and context to a discussion of ideas. Stories can be written to persuade people to make certain purchases or hold certain views. News, advertising and public relations messages perform some or all of these functions while employing different storytelling techniques and formats to communicate with audiences in the most effective way.

There are a number of different storytelling decisions to make as a producer of media content. Regardless of which type of media you are working within, it is important that you, the communicator, are aware of the fundamental storytelling devices you might want to use to tell your story in a way that is direct, efficient, and appropriate for the story’s objective. Therefore, you will want to have a full and accessible set of tools that you are ready to employ for any kind of message, depending on the type of media you are creating, your chosen channel of communication, as well as the specific style, tone, and needs of your story subject.

Characteristics of Good Storytelling

Usually the word “story” implies something fictional. But in the case of media messages, “story” refers to fact-based information about products, or events, or the actions taken by a company. The distinction between fiction and non-fiction stories is an absolutely critical one for you to grasp. It affects every decision that you make about the selection and evaluation of information for messages.

Good storytelling consists of knowing your audience. Is the audience going to be reading the story, hearing it, experiencing it in a non-linear fashion online? What kind of background information does the audience for the story already have about the topic?

Good storytelling also begins with a foundation in the subject matter. The storyteller must have a firm grasp of the subject matter in order to effectively communicate the story to someone else.

Good storytelling demands that the storyteller have command of the mechanics of writing.

Good storytelling understands how different media elements play into the effective telling of the story.

Good storytelling demonstrates ethical standards for accuracy, truth, verifiability, sufficient evidence, and information reliability. Non-fiction stories, especially, require a solid grounding in factual information that can withstand scrutiny by the most skeptical audience members.

Storytellers must deliver within the parameters and requirements of the story assignment.

They must:

- meet the deadline

- follow directions on the expected length and focus for the story

- meet the expectation for clean, distribution-ready copy

- use proper grammar, word choice, and style

- apply the appropriate story characteristics for the channel of message delivery

The information strategy skills you will learn in this course will provide you with the tools you need to meet these storytelling requirements. Moving confidently through the information strategy process will help you identify your audience, locate the relevant content for your message, ensure the accuracy of your information and provide the details that will make your message stand out.

Question Analysis: From Assignment to Message

As students, you’ve all dealt with frustratingly ambiguous assignments. Knowing how many pages you are required to write, how the document should be formatted, whether and how to cite the information used – all of these are specifics of the assignment that you hope your instructors spell out for you. If those specifics aren’t clear, you ask your teachers to give you more detail on the parameters of the assignment and on the “metrics” that will be used to judge the quality of the work you turn in.

When on the job, the assignments you get will usually not have this level of detail. In fact, “deals well with ambiguity” is often a line on job descriptions about the ideal candidate. Clarifying the task will be one of the first steps the communicator must take when a supervisor throws out an assignment like, “One of our clients is interested in exploring e-wallets. What do we know about them?” or “We have to do a better job of getting legislators to understand our company. Do an analysis.” or “There have been lots of motorcycle accidents in the past month – we ought to do an in-depth story.”

Determining as completely as possible the “context” for the message will help you begin to put parameters around the task.

In this lesson, we will discuss the aspects of a message assignment that you should clarify with the “gatekeeper.” The more you know about what the “gatekeeper” in a communications organization looks for and values, the more you will be able to pursue a strategy that leads you to successfully fulfilling the message mission.

Understanding the Gatekeeper Audience

As we will discuss in Lesson 4, determining and researching the key audience for the message you will be creating is one of the most important parts of message development. But there is another, perhaps even more, the important initial audience for your work, and that is the person in the organization who will approve, support, or squash your ideas.

.jpg)

Referred to as “gatekeepers” these are the people within the organization who not only hand out the assignments, they are also the ones with the power to decide:

- which messages are produced

- who produces the messages

- where the messages will appear

- what the messages will contain

Examples of “gatekeepers” in communications or business organizations include:

- a newspaper’s assistant managing editors who assign stories to appropriate reporters

- a television station’s producers and assignment editors

- advertising agency account executives

- public relations firm client services managers

- a corporation’s chief communications officer who decides whether the new communications plan is ready to present to the CEO

An important function of gatekeepers is to maintain the standards and the “voice” that define the specific organization for which they are “keeping the gates.”

Within a newspaper organization, the assistant managing editor who assigns stories to various reporters on a beat has the responsibility to decide whether the reporters’ stories are acceptable before the stories are sent along to the next step in the process of getting printed in the newspaper and posted online.

Reporters learn to anticipate the kinds of stories that their editors (the gatekeeper audience members) want. One editor may respond positively every time a reporter writes a story that includes a quote from a particular source. That reporter will try to include that source in her stories as often as possible. In a television news operation, the newscast producer might respond well every time a reporter/photographer team does a story that is accompanied by particular types of images. Again, that reporter/photographer team will try as often as possible to select that type of video to please the producer and thus assure a spot on the newscast.

In an advertising agency, the account management professionals perform a similar gatekeeper function. Client services managers in a PR firm perform the same function. They are responsible for contact with the client who is paying to have the ads created or the public relations work done. If the account manager is unhappy with the advertising or PR campaign that the other professionals have created, it may not get passed along for client approval. Communicators learn to adjust their efforts and create ads or PR work that account managers or client services managers are most likely to define as acceptable and ready for client review.

In a business, non-profit organization, government agency or similar type of institution, the communications manager for the organization plays the gatekeeper role. Any content that appears on the organization’s website, the social media content that is produced, the promotions sent to mobile devices and any other messages directed at the public go through a review process. Communicators inside an organization have to conform to the rules, processes and expectations of the communications manager if their work is going to be delivered to audiences.

At the initial stage in the message, process gatekeepers are the ones who will be issuing assignments. They are the ones who will determine if you delivered what was requested and they are the ones you will need to work with to clarify the assignment so you have the best chance of successfully delivering what is needed.

Gatekeepers will have in mind the needs of the ultimate “client” for whatever work you produce. The editor of a publication will understand who the readers are and what they look for in the articles that run. The PR client manager will understand the objectives of the client for the campaign. The advertising account manager will know the advertiser’s sales goals. The corporate communications manager will know what image the company is trying to project. Your job is to interpret the work assignment given to you and know how the work you produce will ultimately help everyone’s objectives be met.

Journalist Checklist for Public Relations

The “5 Ws and H” (Who, What, When, Where, Why, and How) checklist that journalists use in covering a story or that strategic communicators would need to consider when developing a campaign can be used with a slightly different orientation for communicators who need to clarify an assignment.

Let’s imagine that in the strategic communications context your boss sends the following text: “Our client is interested in exploring bitcoin. See what you can find out.” Or in the newsroom, your editor drops by and says, “The Times had a big story about bitcoin. Should we cover this?” How do you even start? In upcoming lessons we will delve into the kinds of questions you’ll ask and answer when developing a research agenda (who is the audience, what are the angles of the topic, where might you find information.) But before you can begin to understand the specifics of the research task itself you need further clarification about the gatekeeper’s expectations. Following are some of the kinds of questions you might ask to clarify the assignment.

WHO? Who will be seeing the report you produce? This will give you clues as to the nature of the language to use, the formality or informality of the report you deliver. Previous experience with this person or team will inform you about their expectations.

WHAT? What form should the information take? Learn if this is just an informal backgrounder, information needed to justify a whole new campaign or series idea, or a competitive intelligence report. Knowing what type of report or document is expected will help you set a framework for the task.

WHEN?When is the work to be delivered? Knowing the deadline or desired delivery date for your work will help you gauge what level of work can be done (and help you manage your boss’s expectations.)

WHERE? Where will the report be delivered? Do they want a written report, a briefing at a meeting, a document shared on the office cloud?

WHY? Why is the information needed? Is a campaign / series already planned and they need concrete information to move the plan forward? Is this just exploratory to see if there is justification for a particular direction?

Once these questions are answered, the HOW to begin researching will be much easier to answer.

Most of the assignments you are given are intended to ultimately lead to a communications message of some type. Whether it will result in a news release, or a new advertising campaign, or a news story, knowing as much as possible about the intended outcome of the research work you do will help you understand the amount and type of information you’ll need to research.

Although the answers to these questions might be revealed later in the process, it is important to understand that the answers will help form your information strategy.

Message Purpose

Another important consideration when clarifying a message task is to determine the ultimate purpose of the message. Messages fulfill seven functions:

- they provide information about the availability of products and services: advertising and publicity

- they entertain: special features, advertising

- they inform: basic news, advertising, publicity

- they provide a forum for ideas: editorials, interpretive stories, documentaries, commentaries

- they educate: depth stories, self-help stories and columns, informative pieces, advertising with product features and characteristics

- they serve as a watchdog on government: investigative pieces and straight coverage of trials and other public events

- they persuade: advertising, publicity, editorials and commentaries

Communicators pay attention to these expectations as they seek information for messages. In order for a message to have audience appeal, it must meet the audience’s expectations in purpose and form. Analyzing the context for a message includes the task of clearly understanding the purpose of the message. All of the subsequent information-gathering steps are affected by this basic requirement.

Time / Space

Messages must be tailored to meet the time and space constraints imposed by the context within which the message is being created. You cannot explore all the information available for every message on every occasion. Deadlines and costs involved in collecting some information forces you to make choices about particular angles and information sources.

A long, interpretive news story on which a reporter might work for days must use many information sources. That stands in contrast to a breaking news story about a fire that must be posted immediately to the news website or sent out as a 140-character tweet.

The brand advertising campaign that will run over many months and include ads in several media is likely to rest on a large information base. But one retail ad placed in a local newspaper by the neighborhood shoe store does not require such an extensive information search. You make choices about the management of both time and money based on the time and space constraints of your message task.

Time factors in broadcast news, for example, may be the major information constraints. If you have just 1 minute and 20 seconds to tell a story with words and pictures, you must tailor the information strategy to help in identifying the most efficient sources for telling that story.

Space factors may be the major information constraints for a message that will be delivered on a mobile device. The efficient information search is essential to the audience’s expectation of effective storytelling and the media organization’s requirement for the economy in producing a message.

Formats / Channels

An important consideration when developing a research plan is the ultimate delivery method for whatever will be produced. You will learn a great deal in your reporting or strategic writing classes about how the format and channel(s) used for your message affect the actual creation of the message. For the purposes of clarifying your information task, consideration of format and channels can help define the scope of information needed.

For example, if you are assigned to cover a trial and expected to simply tweet ongoing developments, the information you need will be gleaned from your eye-witness account of the proceedings. But if you are expected to develop an in-depth story to run online and in the newspaper that will comprehensively explain the case, you will need deeper background, sources that can help you describe and explain facets of the cases from different perspectives, advice or insight from experts. Producing the story for a video news report will require finding sources you can get on camera or researching locations that can give visual appeal to the story.

If you understand from your assignment that the ultimate output of your work will be recommendations on a key message to display on a billboard it will make the scope of your information seeking different than if you are creating a multi-channel campaign.

All of these message context issues must be analyzed at the start of an information search. In upcoming lessons, we will begin to develop techniques for asking, and answering, questions about the audience for the message, the facet or angles of the topic or product being researched, and who are the likely sources of information on the topic. But it is only after asking and answering the basic questions about the initial task assignment that you can begin to delve into the creative work of developing a more clearly outlined information process. The rest of the information strategy is highly dependent on the parameters of the information task.

- How to Get Clear Direction from your Boss, by Alexandra Levit, posted 3/18/13.

- Resolving Ambiguity and Uncertainty, posted 9/22/12.

Question Analysis: Who’s the Audience?

Types of Audiences

As we begin the process of analyzing the message assignment archery might be a good metaphor to use. If the arrow is your message, the audience is the target you are shooting for. Without the audience “target” your soaring arrow will just fly through the air and land uselessly. Scoping out the target helps you adjust the way you deploy the arrow to most effectively hit the bullseye. Whether you are working in a newsroom or in an advertising or public relations context, your ultimate goal as a communicator is to create messages / stories / advertisements / public relations materials that effectively engage the audience with whom you most want to connect. It is your ability to connect the message content with the valued audience that will determine how successful your communications effort has been.Advertisers want to expand their products’ market reach. The advertising communicator’s job, then, is to determine the story to tell about the product that will most effectively appeal to the audience that has been targeted for that expanded reach. They need to understand who the current audience is for the product.Questions advertisers will ask about audience include:

- Who is the product not currently effectively marketed to?

- What do the people who use the product like, or dislike about the product?

- Who are the people who use a competitor’s product and what do the competitors in the marketplace offer?

- What would an ideal customer for the product look like?

- Who buys similar products and who might find this product attractive?

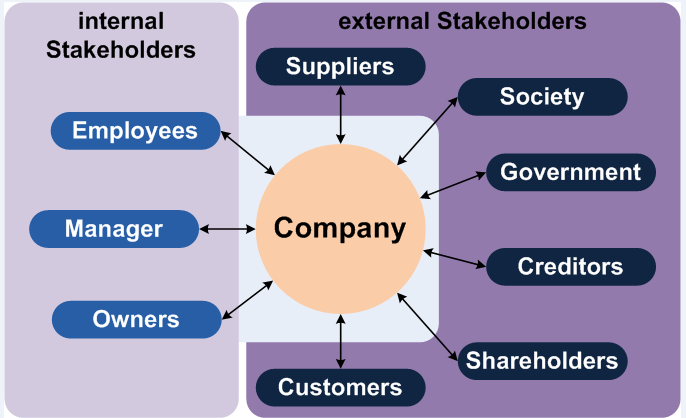

Public relations professionals want to ensure positive opinions about their organization. The public relations professional’s task, then, is to create messages that will influence the important stakeholders.

Questions public relations professionals will ask about audience include:

- Who are the people or groups we need to influence?

- What concerns might different stakeholders have?

- What impact would negative opinion by certain stakeholders have on the company?

Journalists’ communications work is intended to inform, entertain, persuade, mobilize and/or engage the readers or viewers of the publications for which they work.

Questions journalists will include about audience:

- Who is reading/listening/viewing the news message?

- What is it that that audience already knows?

- What does the audience need to know?

As these examples indicate, each type of communicator has different types of people that they need to keep in mind and they need to understand different things about that audience they will be targeting. Before we discuss how to analyze these audience needs, we should point out two other audiences that communicators must consider as they develop their message.

Gatekeepers

We’ve already introduced the concept of the “gatekeepers” and their importance in the message creation process. At the start of an information task, the most important audience might be the organizational gatekeeper who will give you an assignment and who you must please with your work. Journalists will want to keep the editor in mind as they set out to define the parameters of the assignment and strategic communicators will need to be sure they understand what their boss needs. Researching these “audiences” will be an on-the-job task and can require a clear conversation to clarify the assignment as discussed in Lesson 3. The gatekeepers’ concern is that the message is constructed in such a way that the goal of communication is accomplished.

Colleagues and Professionals

Communicators also keep in mind their colleagues or professional audiences when they consider how best to accomplish a message task. These are the people you work with and others in the same profession who you want to influence or impress.

For example, public relations professionals quickly learn to produce news releases that fit the formula sought by the media organizations they are trying to influence. The only way to be effective with a news release is to have a news organization “pick it up” or run a story based on it (this is why PR is referred to as “earned media.”) Effective PR specialists are those who can mimic the news style of their colleagues in the local media market and tailor their news releases so that they get the maximum exposure. In this case, the colleagues in the news organization are both part of the colleague AND the gatekeeper audience. Similarly, reporters might be tempted to write their stories in a way that they know (consciously or unconsciously) will avoid offending their most important sources (the professionals from whom they have to seek information on a regular basis).

Some advertising copywriters and art directors create ads with the hope that they will get nominated for the advertising awards that help boost careers and increase salaries. The awards are almost always judged by fellow advertising professionals.

These colleagues or professional audience members exert an enormous influence on the way communicators in all media industries do their work. Communicators rely heavily on each other for ideas, and the rewards in most areas of communication work are measured by professional reputation and recognition rather than by high salaries. It is not surprising that communicators seek to create messages that will garner attention and recognition from peers in the industry.

Also, many communicators, especially those who work in news, are heavily reliant on information provided by others (government officials, industry sources, etc.). Therefore, communicators might be reluctant to do anything objectionable that will cause someone to “turn off” the information flow. That is one of the reasons news organizations may rotate journalists off a specific beat – they don’t want reporters to get too close to their sources.

And all communicators understand that if the communications they create are seen as unethical or irresponsible it harms not only their own professional careers but the credibility of the entire professional.

As important as it is to recognize the gatekeeper and colleague audiences when constructing a message, it is ultimately the target audience for the message that requires creative and careful consideration. Understanding to whom the message will be directed and doing the research to ensure you have identified and understand that “end-user” is a critical, and complicated, skill.

Target Audience

This is the audience that most people think of when they hear the word. But all audience members are not identical. Therefore, communication researchers have devised many ways to categorize the target audience. Let’s look at the the various ways target audiences might be understood.

Target Audience Segments

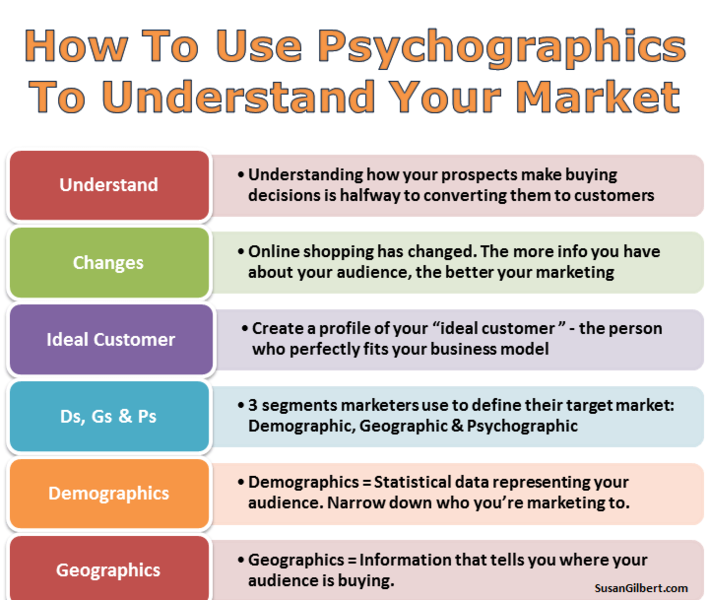

One way to distinguish different types of audience members is to identify the audience segment(s) into which someone might fall. Communications professionals, and especially advertisers, use a number of categories to more precisely identify who they should target with messages. Audience members can be segmented according to demographic, geographic or psychographic characteristics, or some combination of those categories. There are a number of sophisticated research tools and sources that provide detailed information about these types of categories for audience analysis.

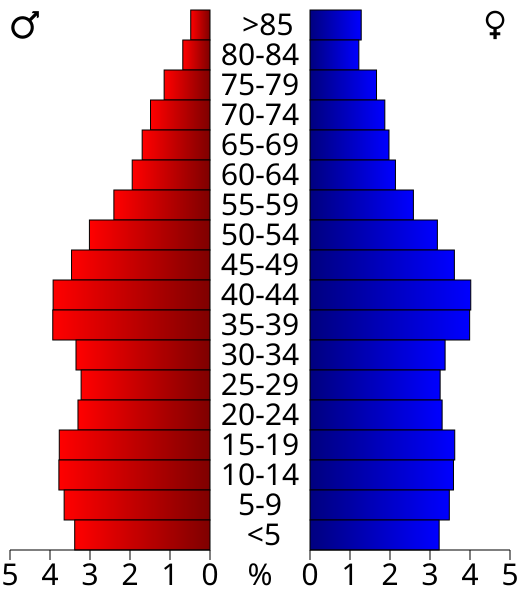

Audience Segments: Demographics

There are social and economic characteristics that can influence how someone behaves as an individual. Standard demographic variables include a person’s age, gender, family status, education, occupation, income, race and ethnicity. Each of these variables or characteristics can provide clues about how a person might respond to a message.

Advertisers are clearly interested in knowing, for instance, how age influences a person’s need for goods and services. Think about the kinds of items teenagers purchase, the programs they watch on TV and online, and the magazines they read. Advertisers then compare those to the products that their parents purchase, the programs they watch, and the magazines they read.

The influence of an audience member’s age is also a factor in the types of news messages that appeal to one group versus another. Younger people (teens, young adults) generally do not watch the national evening news on television or read a daily newspaper, for example. The news stories on those programs or in the newspaper reflect the knowledge that the audience is more mature, settled, and concerned about different topics and issues than are the younger members of the household. Each of the other demographic variables mentioned can be examined for their influence on messages and how they are tailored to meet specific audience characteristics.

Audience Segments: Geographics

We all understand geographically-defined political jurisdictions such as cities, counties, and states. These are important geographic audience categories for politicians and for news stories or ads about politics and elections. Also, local retail advertisers want to reach audiences who are in the reading or listening range of the local newspaper or radio station and within traveling distance of their stores. The audience for a newspaper is generally defined as those within a specific metropolitan area–stories and ads are written to appeal to the residents of a well-defined locality. Local television stations tailor their messages to the audience reached by their broadcast signal.

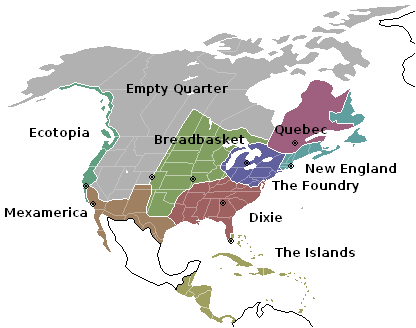

Larger, more abstract geographic definitions help define the audience for national advertisers and those creating news or public relations messages for a regional or national audience. Washington Post reporter Joel Garreau (1989) argued that regional differences in North America (Canada, the U.S., and Mexico) are important markers for understanding differences in populations that span a continent. He invented nine “nations” or non-political regions whose boundaries don’t correspond to any current political jurisdictions. They are New England, The Foundry, Dixie, The Islands, MexAmerica, Breadbasket, Ecotopia, The Empty Quarter, and Quebec.

For one example of how Garreau determined the boundaries for each “nation,” we can look at his examination of three major cities in Texas. By political considerations, the three are all part of one jurisdiction: the state of Texas. But to Garreau, Fort Worth is actually part of the Breadbasket because of its strong cattle-town heritage; San Antonio, with its large, urban Spanish-speaking community fits into MexAmerica; and Dallas is part of Dixie, with dramatic social change and economic growth.

These distinctions may be irrelevant to those who draw political boundaries, but the cultural implications are crucial for those who create messages. Audience members for some types of messages in San Antonio cannot be characterized as “Texans” or even “Southerners” if one of their main cultural and regional identifiers is their close affiliation with other inhabitants of “MexAmerica.” Garreau’s characterizations have been widely accepted by media professionals, businesses and social scientists around the country.

Another geographic definition segments audiences into rural, urban, suburban, and edge communities (the office parks that have sprung up on the outskirts of many urban communities). These geographic categories help define rifts between regions on issues such as transportation, education, taxes, housing and land use.

Politicians have long understood that voters can be defined using these types of categories. Those who create media messages pay attention to these categories as well. Newspaper publishers in major metropolitan areas, for example, have long struggled with how to maintain their focus on the central city that defines the newspaper, while also attracting and keeping readers who live in the suburbs and work in an edge community high-rise office building.

Demographic and geographic audience characteristics are gathered from many sources. These include the U.S. Census as well as thousands of individual studies and research services conducted by media industry professionals.

Audience Segments: Psychographics

Psychographics refers to all of the psychological variables that combine to form a person’s inner self. Even if two people share the same demographic or geographic characteristics, they may still hold entirely different ideas and values that define them personally and socially. Some of these differences are explained by looking at the psychographic characteristics that define them. Psychographic variables include:

Motives – an internal force that stimulates someone to behave in a particular manner. A person has media consumption motives and buying motives. A motive for watching television may be to escape; a motive for choosing to watch a situation comedy rather than a police drama may be the audience member’s need to laugh rather than feel suspense and anxiety.

Attitudes – a learned predisposition, a feeling held toward an object, person or idea that leads to a particular behaviour. Attitudes are enduring; they are positive or negative, affecting likes and dislikes. A strong positive attitude can make someone very loyal to a brand (one person is committed to the Mazda brand so she will only consider Mazda models when it is time to buy a new car). A strong negative attitude can turn an audience member away from a message or product (someone disagrees with the political slant of Fox News and decides to watch MSNBC instead).

Personalities – a collection of traits that make a person distinctive. Personalities influence how people look at the world, how they perceive and interpret what is happening around them, how they respond intellectually and emotionally, how they form opinions and attitudes.

Lifestyles – these factors form the mainstay of psychographic research. Lifestyle research studies the way people allocate time, energy and money. One of the most well-known lifestyle models is the Values and Lifestyles System (VALS™) devised by research firm Strategic Business Insights. The model categorizes people according to their psychological characteristics and their resources. Advertisers use it to determine what kind of products and advertising appeals will best work with an anonymous audience member who falls into one of the eight categories, or mindsets, in the VALS™ model.

For example, someone who falls into the “Striver” category is said to be seeking self-definition, motivation and approval, and is low on economic, social and psychological resources. The “Innovator” group is comprised of successful people with high self-esteem and high income, with a wide range of interests and a taste for finer things.

These categories are most useful for advertisers in helping determine a “unique selling proposition” that would be most appealing to one type of person or another, but they also help other message creators understand WHY advertisers support the types of media they do and why some types of messages are created while others are not.

Combining Segment Data

As audience segmentation techniques become more sophisticated, we see new ways of organizing and clustering individuals according to a combination of characteristics. For instance, the Jefferson Institute has created a project called “Patchwork Nation.”

According to their website, Patchwork Nation “aims to explore what is happening in the United States by examining different kinds of communities over time. The effort uses demographic, voting and cultural data to cluster and organize communities into ‘types of place.’ Patchwork divides America’s 3,141 counties into 12 community types based on characteristics such as income level, racial composition, employment and religion. It also breaks the nation’s 435 congressional districts into nine categories, using the same data points and clustering techniques.”

The characteristics of Patchwork Nation locations incorporate demographic, psychographic and political data to generate a map of the country that might be used to define an advertising audience, explain voter behaviour for a news story, or target a community for a PR campaign. Examining the elements of regional characteristics can give you ideas about the diversity of audiences and an appreciation for the challenge of understanding how best to reach specific segments.

News

Journalists produce their work with the readers, listeners or viewers of the publication for which they work in mind. A journalist who works for the daily news organization in a town needs to understand the characteristics of subscribers. And if they work for a particular beat, for example, the business section, they need to understand what it is that readers of that section are looking for and how they would use the information they get.

Why does this matter? If journalists don’t create stories that inform and engage their audience those people will find other outlets to satisfy their information needs. Journalism serves not only a public need, but it is also a business and a business without customers won’t be in business for long.

News organizations conduct user surveys and track audience behaviour just as other kinds of companies do. The better journalists are able to understand their readership the better they will be able to anticipate and address their audience’s needs.

For those journalists who work as freelancers (defined by Merriam-Webster as “a person who pursues a profession without a long-term commitment to any one employer”), it is essential that they learn about the target audience for the publication to which they want to pitch a story. If they don’t understand the characteristics of the audience who reads Sports Illustrated versus The Atlantic, they will not be able to effectively position (or “pitch”) their story idea.

In the case of pitching a story idea, they need to understand that the publication’s editor is the ultimate decider on whether they get the assignment or not, and the editor’s ultimate concern is to keep the publication’s audience satisfied. In order for the freelancer to get the “gatekeeper’s” go-ahead on a story idea, they must demonstrate they understand who the target audience is for the publication and what will appeal to them.

Advertising

In an age of increasing competition and consumer choice, advertisers must have a highly developed understanding of the audience (customers or consumers) they want to reach. Audience research is, perhaps, the biggest information gathering task for advertisers. Information about potential or desired audiences is required at every stage of developing an advertising campaign.

The kinds of questions an advertiser will want to answer about their potential audience include:

- Who are our current customers? You need to know who you are already reaching, and how to keep them as satisfied customers.

- Who are our competitors’ customers? Understanding who uses the competitors’ products or services is key to figuring out how to create a campaign that could convince them to try your company’s products.

- What do our desired audience members watch / read? Knowing where to find the kinds of customers you want to attract is an essential part of media buying work. The dollars spent placing advertisements will be thrown away if the message doesn’t reach the audience you desire.

- How happy are our customers with our products? Keeping a pulse on consumer attitude and opinion of your product will help to refine the story you want to tell.

Until you have a set of questions to ask about the target audience, you won’t know how to go about finding answers.

Public Relations

In public relations work, the target audience is often referred to as the “stakeholder.” Defined by Merriam-Webster as “one who is involved in or affected by a course of action” the stakeholders are those groups of people that an organization must positively influence. Just as the advertising message is intended to influence customers to regard your product positively, the public relations message is intended to influence stakeholders to regard your organization positively.

Stakeholders whose opinions or actions can positively or negatively affect an organization include:

- Customers: people who don’t feel good about a company won’t buy their products

- Investors: bankers, stockholders, financial analysts and others who have committed (or advise others to commit) funding to an organization won’t maintain their support if they don’t believe in what the company is doing

- Legislators / government regulators: lawmakers who feel a company or industry is doing harm, or who get complaints from their constituents, will be likely to propose restrictions or regulations

- Employees: the people who work within an organization must have high regard for their employer or they won’t be good representatives of the organization

- Activists / philanthropic groups: organizations that have an interest in the area in which the organization operates can exert economic or policy pressure if they don’t support the organization’s work

- Business partners: most organizations work with a network of suppliers, vendors, and other types of business partners who help them maintain their position in their industry or field; partners are an important stakeholder audience for PR professionals

Who’s the Audience for News?

In some ways, the audience for journalistic messages is the most concrete and pre-determined of the three communications professions’ work. Journalists write for publications or produce reports for media outlets that have a great deal of information about their subscribers or viewers. With the ability to track digital readership, journalists know what articles people read. At the start of the message analysis process, journalists must ask a set of questions about their target audience that will help them identify the treatment of the topic about which they will be writing and make decisions about the kind of reporting they must do.

Understanding the audience that uses the publication or media outlet for which they are producing a news report will help clarify some of the following questions:

- WHO: Who reads / views the publication? Who would be interested in this topic? Who needs to know about this topic? Who is the media organization interested in attracting with its offerings?

- WHAT: What would the potential audience member want to know about the topic? What kind of report would be most informative or helpful for the audience? What kind of information will be useful? What does the audience already know about this?

- WHERE: Where else do people interested in the topic find information? (For freelancers) Where should I pitch my story idea?

- WHEN: When does the audience need to get this information (is this fast-breaking news, or something that will be used as analysis after the event?)

- WHY: Why does the audience need to know this? Why does the audience care? Sometimes the audience member just wants to fill empty minutes with a news message (reading news briefs on a mobile device while standing in a line or eating alone at a restaurant). Sometimes the audience member needs to answer a specific question (who won the baseball game this afternoon? when does the movie start?). Each of these “why” questions suggests a different strategy for the communicator.

- HOW: How can we best communicate to the audience? How much background do they need to understand what we are writing about? How technical can we be? How might the audience react to this report?

Who’s the Audience for Advertising?

Advertising professionals have also developed a standard set of questions that they ask at the start of a message task, many of which specifically address audience considerations. These questions also address elements of the subject matter of the ads, the best approaches for creating the ad copy and placing the ads in the most appropriate vehicles. We will come back to many of these questions in subsequent lessons.

- What should our advertising accomplish? Again, sometimes the audience member just needs to find a nearby place to buy a specific product, or the hours and phone number of a business. Filling that immediate information need for the audience member requires a different strategy than trying to encourage the audience member to change their brand loyalty, think positively about your service, purchase your product. You want to know if the ad is intended to fill an immediate information need or to include a “call to action” on the part of the audience member.

Montaña Rusa Hopi Hari by Arturo de Albornoz. Source: Flickr. CC BY-SA 2.0. - To whom should we advertise? Who was the target audience in previous campaigns and who has not been targeted yet that should be? Who are the competitors’ customers?

- What should we say that will most effectively convince the audience to respond to our call to action? What have our client’s ads said to similar audiences in the past? What do our client’s competitors’ ads say?

- How should we frame our message for this specific audience? How will our proposed creative strategies work for this client’s messages? How do our competitors position their creative strategies?

- Where should we place or message to reach this audience most effectively? Which media will best reach our target audience?

- How much should we spend in order to reach this audience in a cost-effective way? What has our client spent in the past? How much do our competitors spend?

Who’s the Audience for Public Relations?

Public relations professionals ask a similar set of questions when they are doing their strategic planning research. Again, these questions apply not just to the audience aspects of the message task but also to the other parts of the information strategy process.