2.5 A dual perspective

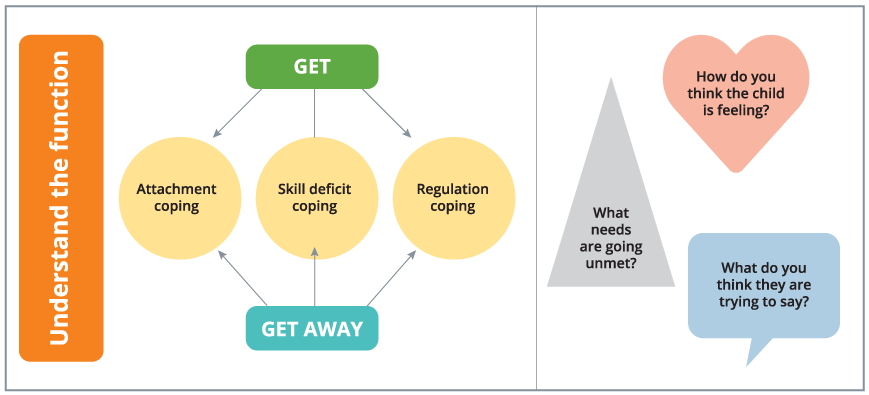

The two functions of challenging student behaviour from a behaviourist perspective are to get something (a person, object, activity or sensory situation) or to escape or to get away (from a person, activity, object or sensory situation). We closely observe and reflect on the relationship between the behaviour and the environment using the ABC. What happened immediately before the behaviour (the antecedent- A), describe the behaviour in observable and measurable terms (the behaviour – B) and carefully assess what happened immediately after the behaviour asking what did the adults do? (consequences – C). This information is then used to inform our best guess (hypothesis) as to what the purpose or function of the behaviour could be. At the same time, the impact that trauma has on the child and their difficulty to learn and behave in an appropriate manner, is clearly understood.

When behaviour is trauma-driven, the child is in survival mode and they do not know “why” they are responding in the way they are. Asking the child affected by trauma, why they did what they did, is unreasonable and most children will not be able to articulate the reason or have any understanding of why. Asking the child “why” serves very little, if any purpose other than to perhaps retraumatise and increasing feelings of shame and unworthiness. What these children need, is for the adults to work out the “why” to guide and help them learn how to cope with being in a learning environment and demonstrate prosocial behaviours.

When hypothesising about the possible function of the challenging behaviour, knowledge of attachment, skills deficits and regulation coping are drawn upon to better inform behaviour interventions for those children who may have experienced trauma. The diagram below illustrates the relationship between the key elements of the transtheoretical trauma informed behaviour support model when considering how to give our best effort to help the children with trauma experience success at school.

It is important to remember that all children with trauma are individuals who react in very different ways and many will not demonstrate highly disruptive behaviour. However, many do, and it is critical that teachers look at any challenging behaviour as behaviour that possibly could be trauma-based.

Be mindful of teacher behaviour and strategies that are commonplace for example sending a child to time-out, to consider their behaviour may trigger retraumatisation for the child affected by trauma. Being ‘sent away’ is likely to stir up feelings of abandonment and isolation and reinforce the child’s view that they are not worthy of adult love and care.

When faced with challenging student behaviour, teachers with an understanding of elements of the transtheoretical model know that functioning in a school situation is an extremely ‘big ask’ for some children with trauma histories. The fact that these children show up to school at all, is testament to their resilience and strength. Tread carefully and considerately and walk beside them. Be there. Be kind.

![]() Interview with Tom Brunzell [41 min]

Interview with Tom Brunzell [41 min]

Listen to the interview with Tom from Berry Street in Melbourne on positive psychology for traumatised children.

![]()

Through Our Eyes: Children, Violence and Trauma [7 mins 53 secs]

This video discusses how violence and trauma affect children, including the serious and long-lasting consequences for their physical and mental health; signs that a child may be exposed to violence or trauma; and the staggering cost of child maltreatment to families, communities, and the nation.

Please note that the clip contains themes and images that may be distressing to some. Please feel free to stop watching the video if you are distressed.

A transcript and Closed Captions are also available within the video.