4.2 Attachment, school and learning

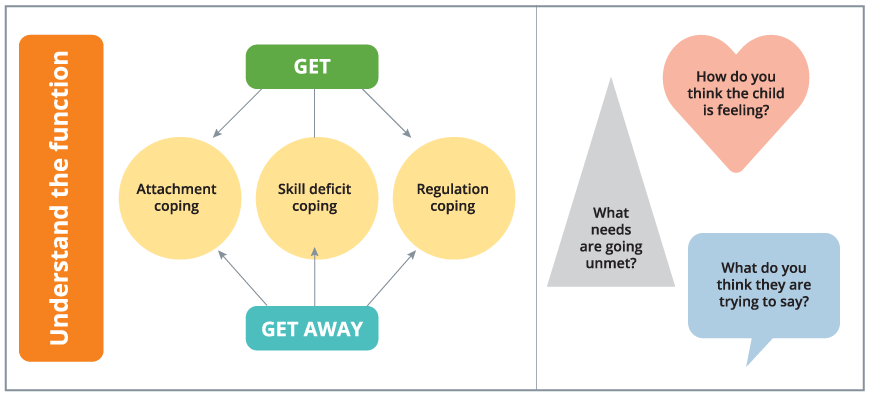

When we are thinking functionally about the function of behaviour in terms of attachment coping, we must start with considering the attachment and relationship styles of the student with trauma. Students who have attachment difficulties engage in misbehaviour in an attempt to cope by ‘getting’ control over people – adults and other children – through coercion, deception and aggression (verbal, physical). These children may have learned to use such behaviours to get them access to preferred activities and objects and proximity to adults. The knowledge of such functions helps us give these students what they need to meet these needs in an appropriate manner, while helping them learn new ways of coping. Instead of seeking control, we can provide these students with a sense of predictability in relationships through explicitly teaching rules, consequences and routines.

Control can also be provided to these students through choices in the classroom – in academic or social activities. The teaching of appropriate social skills – both explicitly and implicitly – help these students leave prosocial and interpersonal ways of having their needs met, while building on a sense of safety and trust in the classroom. These kids may also ‘get away from’ adult and peer relationships by not trusting others, by being hypervigilant about being betrayed, humiliated or taken advantage of, they may withdraw from relationships or act as though they do not require any friendships with peers or support from adults. It is possible that these children have learnt to engage in such behaviours as assertive and appropriate expressions of their needs and feelings to adults in the past has not led to the adults (e.g. parents, carers, other teachers) responding to them in a safe, calm, caring and consistent manner. In this way, misbehaviour represents a miscommunication of the student’s need to feel safe in relationships and be part of a trustworthy and loving community of children and adults.

How are we going to do this? How are we going to put this into practice? Let us look at the following framework to help us.

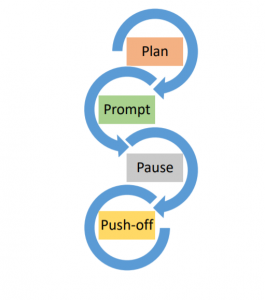

Plan, prompt, pause, push-off

Education Queensland in 2007, published The Essential Skills for Classroom Management (ESCM) as an important component of the Better Behaviour Better Learning professional development program. As the name suggests, the 10 skills outlined are essential to the management of student behaviour in all classrooms from early childhood to secondary and adult learning contexts. As popular today as when first introduced, teachers, both novice and experienced, continue to benefit from learning, practising, embedding and revising, these crucial skills. The 10 essential skills are:

- Establishing expectations

- Giving instructions

- Waiting and scanning

- Cueing with parallel acknowledgement

- Body language encouraging

- Descriptive encouraging

- Selective attending

- Redirecting to the learning

- Giving a choice

- Following through

The terms ‘prompt,’ ‘pause’ and ‘push-off’ used here are from essential skill seven – selective attending and have been adapted to illustrate a trauma informed approach to positive behaviour support. Elements from across the 10 essential skills are inherent in the discussion that follows as part of quality teaching practice and you are encouraged to familiarise yourself with or revise the content of the essential skills so that they become an integral part of your daily classroom practice. We will now look at plan, prompt, pause and push-off in the context of our understanding of the challenging behaviour demonstrated by children with trauma.

Plan

“Planning is our best strategy for prevention.”

It is best to prevent the behaviour from happening in the first place in preference to picking up the pieces after the damage is done. Plan the classroom environment, plan the activities, plan your words, plan your actions, plan your attitude, plan your reinforcement of appropriate behaviour, plan what to do if everything does not go to plan. When planning, the teacher needs to ‘tune in’ to the student to see if they are about to flip their lid? What are the signs for this child that they are not feeling safe, secure and balanced? Are they in their window of tolerance? Is safety an issue?

Prompt

There are two key choices for prompting:

- Follow the child’s lead which means use prompts and strategies to bring the child back into the window of tolerance. Reminding and reinforcing language is used.

- Take charge which means use prompts and strategies to ensure the safety of the child with trauma, the rest of the children, staff and yourself. Connecting and redirecting language is used.

Following the lead of the child demonstrating the challenging behaviour is something teachers need to do as much as possible. Take charge only when necessary. The language used for each of these choices, following their lead and taking charge, is very important to the success of implementation so let us look at each type of language a little more closely.

Reminding language (following their lead): Keep reminders brief, describe and praise appropriate behaviour, use a neutral tone of voice and body language. For example: “Joshua, group time rules.” “We are going to assembly in five minutes. How do we show active listening?”

Reinforcing language (following their lead): Use specific description, model what you expect showing them explicitly what it looks like and sounds like, tell them what they should be doing not what they shouldn’t be doing. Provide plenty of positive feedback. For example: “Thank you for putting your book away immediately.” “You have used capital letters at the beginning of every sentence and remembered the full stops.”

Connecting language (taking charge): Taking charge means being in control without being controlling. Creating connections includes: managing your reactions, consequences not punishment, setting limits, providing choices, acknowledging good decisions and choices that the child makes and supporting parents and carers.

Redirecting language (taking charge): Be respectful and calm, replace questions with commands, be specific, concise and in control, focus on the immediate behaviour that is needed and do not “pick up the rope”. “Do not pick up the rope” means do not get dragged into responding to secondary conversations that the child uses to redirect you away from the focus of the situation. These will sound like “You hate me anyway,” “You never help me when I ask”. “This is too hard”. “This school sucks” and the like. Some examples of specific redirecting language are: “Put that toy away” (not “Do you want me to take that toy?”), “Help Julie pack up the calculators please” (not “Be nice”) “Eyes on me” (not “Will you look at me?”).

Using the PACE model (Hughes, 1997) helps teachers to help the child with trauma feel connected. PACE stands for playfulness, acceptance, curiosity and empathy and helps to find the balance between following their lead and taking charge.

- Playfulness – delighting in the student; reduce fear of making mistakes or getting into trouble all the time. Having fun and using humour to diffuse tension. “I know you don’t like tidy up time so let’s sing while we all tidy up together.”

Tower building blocks by FeeLoona licensed CC0. - Acceptance– separating the behaviour from the child. reinforcing your commitment to them; listening and showing understanding. Focusing on the child and not the behaviour and trying to understand because whatever it is, it makes sense to them and they need to be able to tell you their story. Behaviour limits are set and consequences applied. “I know you find it hard to manage your anger and you will have to help me fix up the mess, but at the moment come and sit with me until you feel calmer.”

- Curiosity and reflection – taking an interest, showing concern, ‘wondering’ out loud. Taking an interest, showing concern, clarifying what you have heard. This is about asking questions you already know the answer for and ‘wondering’ out loud “I wonder if that question means…” “I wonder if you tried,” “I wonder if you had troubles yesterday because you were worried about your mum visiting on the weekend?” Help the child come up with their own solutions.

- Empathy – putting yourself in their shoes. “I am sorry that that happened to you.” “I feel sad for you.” Empathy relieves shame and is much better than praise in many situations which can tend to escalate a negative reaction.

As Hughes (2009) notes, the PACE approach is equally as beneficial for adolescents as it is for younger children. PACE is an attitude and sends the message to the adolescent that the “intention is to come to deeply know, accept, and value the adolescent, joining with him in areas of his life-story that are stressful, confusing or full of conflict and shame” (Hughes, 2009, p. 126). In implementing the PACE attitude and way of working with the adolescent, it is important to match the emotion portrayed through the words and nuances, the talk of the adolescent. If the adolescent speaks quickly and with conviction and agitation for example, the adult needs to respond in the same manner. This reassures the adolescent that the adult is genuinely trying to understand without judgement thus the adolescent will most likely remain engaged in the conversation.

More time listening and less time talking

Establish joint attention. Joint attention means that both people in the conversation are paying genuine attention to each other. They care what the other person is saying rather than biding their time, so they can speak and say what they want to say. Joint attention also reflects a focus on a joint topic that is, a topic both parties are interested in. It is always helpful to follow the adolescent’s lead in the conversation rather than continuously trying to force the conversation the adult’s way. This is not about fixing the child or young person or focusing on problems only.

Having the right intentions

This is where an adult intention of ‘fixing’ the child or young person will not be helpful in developing a relationship where there is a balance of investment of sharing the self, from both parties. The goal is for both the adult and the child or young person to feel they have had a positive impact upon the other, their contribution and place within the relationship is worthwhile for each of them. The ongoing growth of this relationship will be characterised by awareness. The relationship must hold meaning for the child or young person and for the adult to be successful.

Pause

Pausing is a skill that teachers generally are not good at. As a rule, they tend to ‘fill in the quiet spaces’ with teacher talk. It is important that the child is given time to process what has been said and what it is that has been asked of them (this is why having a visual timetable either in words, pictures or both and other alternatives to just ‘talk’ are important for not just the child with trauma and students with autism spectrum disorder, but for all children). The child with trauma often has memory difficulties and may require additional time to comprehend. Give an instruction and wait five seconds before giving another. Paraphrasing is also helpful if the child is having difficulty understanding.

Pressure to provide a response could contribute to anxiety and further reduce the child’s executive functioning (the ability to switch attention from one thing to another, prioritise, make decisions and plan) and engagement.

Push-Off

With children who have experienced trauma the ‘push-off’ strategy is particularly helpful in keeping them calm and giving them space to process and adjust. This is because many have a limited tolerance for proximity and adult contact. As relationships slowly become stronger and more trusting the child may be accepting of the teacher being closer to them for longer. Remember the child with ambivalent attachment who could be clingy? They need to slowly learn to function independently from the teacher, but this all takes time, consideration and care. It is important to remember that ‘push-off’ is not punishment delivered by the teacher. The message to the child is that the teacher is available to the child whenever needed. Push-off is always used in conjunction with the other strategies.

“Be insistent, committed and kind.”

Children with trauma put up barriers to relating and becoming close to teachers and other adults. Think about their experiences with grown-ups and the fact that they have no reason to trust any of them given what has happened to them at the hands of some. Once the relationship is established, they will do everything they can to sabotage it and ensure that the teacher behaves in the way they have come to expect grown-ups to behave and also to further reinforce their belief that they are not worthy of love and care. What they need from teachers is unconditional support and encouragement. Remember, the behaviour of the child who has experienced trauma reflects their history.

![]()

Interview with Dave Ziegler [20 min 47 sec]

Listen to this interview with Dave Ziegler on helping traumatised children learn.