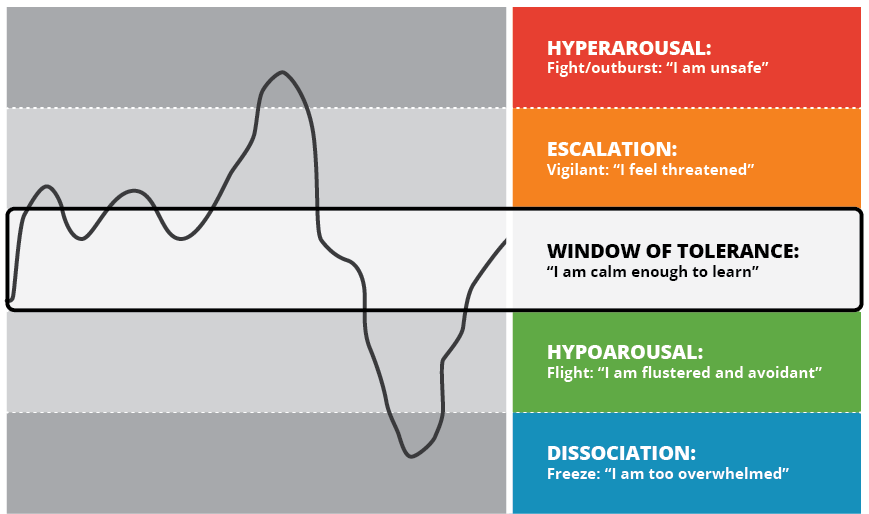

3.6 Using the window of tolerance in the school context

Thinking about introducing and implementing the ‘window of tolerance’ into a school context could be something to consider as a broader teaching group. Some questions to think about:

- Where and by whom would it be best introduced? E.g., in Homeroom or English or Math or to year level group gatherings?

- What are some ways it could be consistently supported across teaching contexts and classrooms?

- What are some ways it could be consistently supported and utilised by coordinators and principals? What are some ways students could be involved in its introduction and implementation?

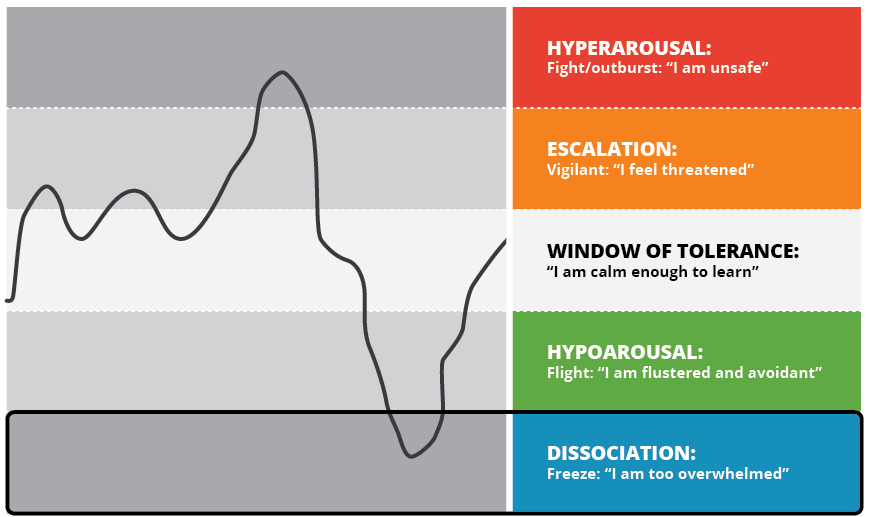

Staying in the window of tolerance

Introduce the window of tolerance model to your students. Talk about examples of when someone might overshoot or undershoot the window paying attention to what that might feel like in the body and normalising that exceeding the window happens for us all at times.

- Represent the window of tolerance concept in a concrete way. For example, it might be drawn on the white board or each student might have an A4 laminated version of the window at their desks.

- Institute window ‘check ins’ throughout class time to gauge views about where the group is at in terms of the window.

- Acknowledge contextual events that may be influencing where everyone is at with regard to their window e.g., approaching exams or social function.

- Model reflecting upon where you are in relation to your window of tolerance. You don’t need to detail underlying reasons.

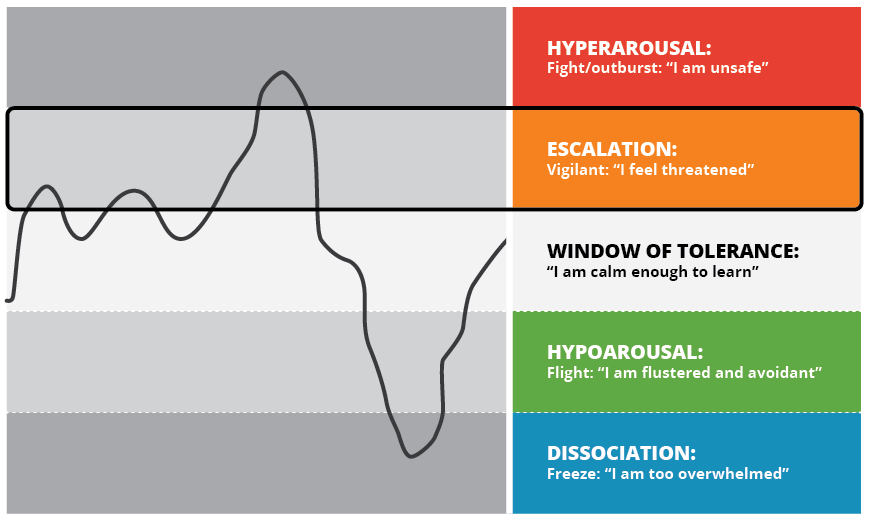

Managing escalation (Orange zone): working with young people who are frequently outside of their window of tolerance

As a first step in working with young people who frequently find themselves outside of their window of tolerance we should acknowledge the important role their protective response/s have played for them in the past. It is wonderful that when they really needed it their brain and body found a way to survive. We also need to help young people hold on to a sense of safety in their daily life as much as possible. It is only when they don’t sense safety that they will need their protective responses. With this in mind you might like to consider the following questions with the young person in a time of calmness:

- Where is the safest place for you at school?

- Where is the safest place for you in the world?

- Is there any way we can help you bring some of that place with you to school?

- Are there people at school that help you feel safe and okay? If so, who?

- Is there anyone you wish you could bring with you to school to help feel okay? (might be from family or a friend or might be a music or sport hero etc.) How might we help you bring something of this person with you to school?

The responses to these questions could contribute to a plan built with the young person to help them more readily hold on to a sense of safety in their every day. The more a young person feels safe at school the less likely it is they will exceed their window of tolerance. Some other ideas for working with young people outside of their window of tolerance:

- Learn more about the body signs of increasing stress for the young person and for yourself.

- Offer students opportunities that will increase their sense of control and power.

- Recalibrate your expectations for young person’s advancement- it may be that they aren’t able to grasp all of the course material and the focus may need to be a social/regulatory one for a time.

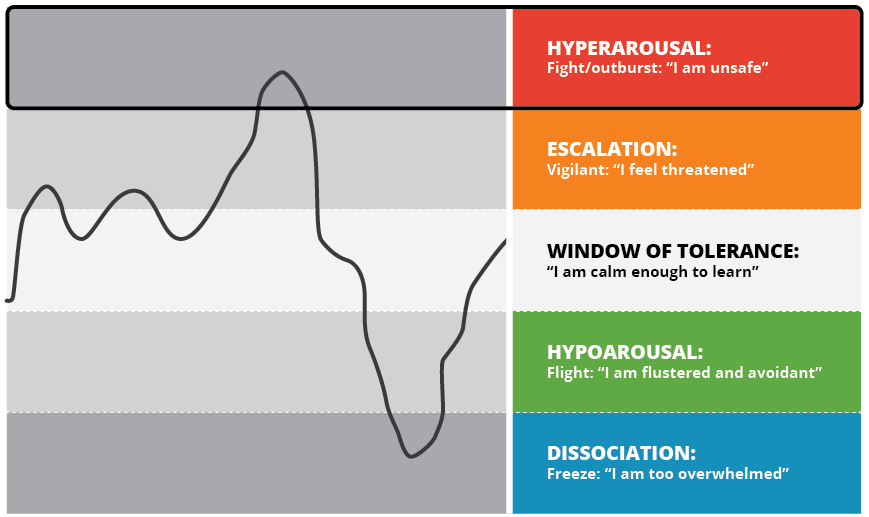

Managing hyperarousal (red zone): working with young people who overshoot their window of tolerance

Children and young people who overshoot their window of tolerance have highly primed nervous systems ready for action. Their systems require calming through activity that allows them to slow down. We need to aim to help these young people find regulating movement. Some ideas for use with these students in the classroom include:

- Intersperse directed group activity breaks- e.g., yawn and stretch breaks, everyone walk once around the room without lifting your feet off the floor or like there is no gravity in the room, initiate Mexican waves, stand up turn around and sit down again.

- Incorporate more kinaesthetic learning opportunities.

- Plan movement breaks with young person- e.g., walk around the oval or opportunity to run an errand or to be able to connect with safest place in school (wherever that is for the young person).

- Plan and practice an escape route with the young person should they need it.

- Work with colleagues and young person to create a plan for if they become activated and practice it.

Some traumatised children will have outbursts of extreme anger and aggression. It is always better to defuse such situations before they become extreme, through the use of the teaching practices described above. However, there are times when you as the teacher will have to respond to the child’s extreme affect dysregulation. At times the practices outlined above will not have been enough, or not enacted soon enough, or the child is experiencing such extremes of emotion they cannot manage themselves. For children who are prone to aggressive outbursts it is important to have a prepared plan of action, detailing who is to do what, when and where. The plan may include calling the parents/carers to help with the child. The child should be included in this planning, so that they know what will happen and have some choice if there is an outburst.

Establish safety

The immediate safety of the child, other students, teachers and staff needs to be ensured. When highly aroused and dysregulated, the child is not able to think clearly or to make good decisions. The child will also be terrified by their own lack of control, which heightens their emotions further. They will need help to calm down, and will not be able to respond to logical requests until they are calmer. For further information refer to the behaviour support policies within the department, service or organisation you are working in.

Maintain self-regulation

The best way to help the extremely dysregulated child is to remain calm and regulated yourself. Use a soothing tone to remind the child that you are helping them to keep safe by removing them to a quiet space where they can calm down. If you are frightened of the child, remove yourself and let someone else take action. Stay close to the child; keep talking; use your presence to help them calm. If the child’s outburst did frighten you, reflect on this later, as it may relate to your own experiences of trauma. Talk to someone about this so that you may be able to assist at another time.

Calm the child

The child may need the presence of a parent or carer in order to become fully calm, or may need some quiet time alone. Many children do better if someone is with them during this time, sitting quietly or talking quietly. Depending on the severity of the event the child may take some time to calm completely and may need to go home rather than return to the classroom.

Assist the child to understand what happened

The child will need time to talk through what happened, and will be better able to do this when fully calm. It is better to pursue this before enacting any necessary discipline. Comment on the child’s strong feelings, and how difficult such events are for everyone. Ask the child to reflect on what was happening for them before and during the event. Children will often respond with “I don’t know”. Say to the child, “It must be hard and confusing not to know how you feel when difficult things happen.” Provide the child with a narrative you have gathered for what happened, being sure to distinguish between what you know and what others have told you. Check that the child has heard and understood, listen to their story and agree to change the narrative if there is a mistake that does not contradict your observation or what you know to be true. Do not enter into an argument with the child about what happened. Children may not tell the truth about the event, or they may blame others for their own behaviour. Make sure the child has heard a comprehensive narrative about the event.

Consequences

Give a clear statement about the consequences. Try to make these natural and fitting for the level of aggression. If the child has broken anything they should fix it, or use their own pocket money to have it fixed, or contribute to having it fixed. If they have hurt someone, they will need to apologise and make restitution, by doing something for the person they have hurt. If school policy is to exclude the child for a period of time, this time should have a structure and a purpose that contributes to the child learning about safe behaviour.

Help the child to take responsibility

The child will often have trouble thinking about the social consequences of their behaviour, and may need help to take responsibility for the hurt they have caused and damage done. This can be a long process that will need therapeutic intervention to be complete. Encourage the child to reflect on the event, and the consequences that have arisen for example, that other children may be frightened of them and not want to play with them. Help the child to re-integrate into the group, and help the other children to accept the child.

Speaking to other children

If other children have been involved in a challenging incident, they may need some debriefing or other attention. If a child has been hurt during a challenging incident, the child’s parents will be upset and want to know what the school is doing about the traumatised child. An injured child will, of course, need prompt attention, and may need support or counselling if badly affected by the incident. The child and their parents will need to be listened to attentively and given an explanation of the traumatised child’s behaviour that does not compromise confidentiality. They will also need an understanding of the school’s plan to manage such incidents in the future. Parents may need several meetings to feel thoroughly heard in these issues. Other children who have witnessed a challenging incident may need an opportunity to talk about the incident and be reassured that they will be safe in the future. A calm, reassuring and contained response by all school personnel is vital to the ongoing healthy functioning of the school.

Review the plan

After a challenging event, find some time to debrief with others involved, and then review the plan with other school personnel, support staff, parents and others, such as therapists and case managers. Did the plan work in the way it was intended? Could anything else have been done, or other support been used? Change the plan as necessary. Make sure the child knows of any changes to the plan.

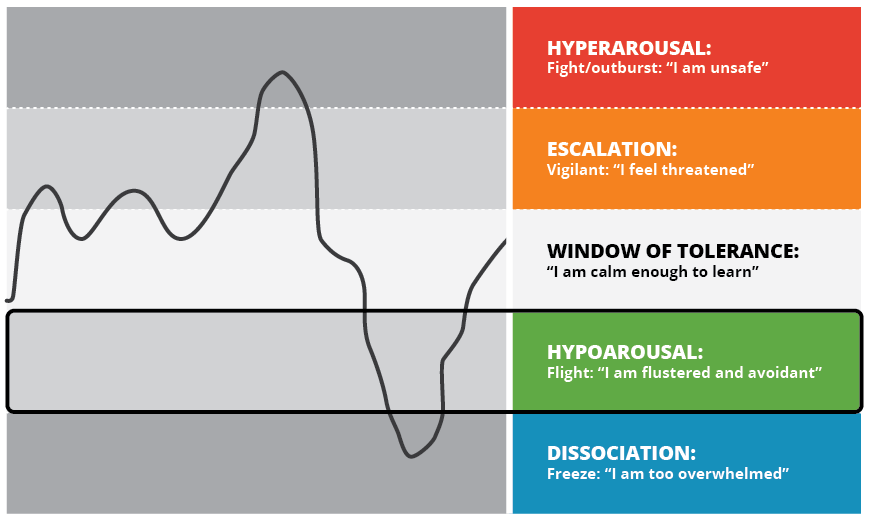

Managing hypoarousal (green zone): working with young people who undershoot their window of tolerance

Young people who undershoot their window of tolerance have nervous systems that can begin to shut down when they lose a sense of safety. These are the students that can become disconnected from themselves and the classroom and require gentle engagement to re-enter their window of tolerance. Some ideas for use with these students in the classroom include introducing short, sharp activities that bring young people into the present moment with a focus on what is happening in the here and now. Some examples include:

- Everyone point to something that’s green.

- Tap your head and rub your belly at the same time, then swap.

- Find out what colour eyes the person next to you has.

- Push your big toes into the bottom of your shoes.

- Sensory stimulation.

- Everyone say three objects you can see, two things you can hear, and one thing you can smell.

- Incorporate kinaesthetic learning opportunities that have a sensory element to them i.e. activities that stimulate many of the senses.

- Create a space in the room for a sensory break e.g., cushion corner with textured cushions and calming posters and play calming music etc.

The window of tolerance is a model we could all apply to our lives. It may be a handy guide to help us better understand the shifting states of the young people we work with, as well as an opportunity to be more reflective about our own windows. It can help us better understand how available our students are to learn at any given time and it can provide us some direction around what a young person might need to re-establish themselves safely within their window of tolerance.

Managing dissociation (blue Zone): working with young people who severely undershoot their window of tolerance

We all use dissociative responses in our everyday lives. Consider any time you focus on one particular task – this means you may not hear someone else speak or not engage in thinking about other topics. Children in particular use dissociation to facilitate their learning.

Abuse related trauma is caused by threatening and overwhelming experiences to children. As children develop, the experiences of trauma induce an avoidant response which becomes a template for engaging with their whole world. The brains of traumatised children move from adaptive survival responses to a generalised protective and defensive state. For children, it is more efficient to operate in this way. Trauma based dissociation stems from a child’s forced absorption with the overwhelming experience of violence and threat. The child is primarily focused on avoiding the pain, shame and hurt of the abuse and comes to develop unconscious, or sub-cortical, responses to try to achieve this. In this abuse related context, dissociation can be seen as the spectrum of strategies, both conscious but particularly sub-conscious, used to not know something.

Dissociative responses stem from the contradictions inherent in the desire to distance the abusive actions with the drive to connect with those who are supposed to care for and respond to the child’s needs. Because these actions are enabled in the lower subcortical or subconscious areas of the brain, children lack the capacity to evaluate and consequently regulate their responses. Children’s responses can be difficult to notice because they are often internalised. The critical point for professional reflection is that these behaviours may impair the child’s capacity to engage with their world. The following list gives an initial understanding of these manifestations. It is by no means exhaustive.

- Fluctuating attention ranging from minor ‘vague outs’ to trance states or blackouts. You might say something to yourself like, “This child is not even listening to me” or “I really don’t think this child is understanding what I’m saying”.

- Fluctuating moods and behaviour which might have you saying, “This behaviour is like it’s from another child!”

- The child talks about alternate selves or imaginary friends who are controlling their behaviour. You might reflect that, “I have never heard an imaginary friend described like that before”.

- Depersonalisation or feeling disconnected from self. You might have an experience where the child doesn’t recognise themselves in the class photo.

Boy in polo shirt licensed under CC0. - Derealisation or feeling disconnected from the world. You may not even notice this occurrence but the child might talk about or experience the world as being “foggy” or “like I’m in a movie”.

- Withdrawing from all external stimuli or communication. There may be a description of this child as, ‘completely shut down’.

- No response to questions or answers them in an unclear and unfocused way. Again you may think “That child is just not listening to me.”

- Gazing into the distance. Your reflection may be that, “this is just not a child who is thinking about their weekend plans”.

- Intrusive thoughts and feelings, including flashbacks. You may notice, “that child really is uncomfortable when I ask the class to close their eyes”.

- Numbness- both physical and emotional. You may note to yourself, “this child doesn’t seem to respond when I touch them”.

- Self-injury. You are more likely to notice this or be informed of concerns for the child by their friends.

- Excessively compliant behaviour. This can be the most difficult because you are most likely to think, “this child is so good- they seem to be dealing with their experiences really well”.

You, as the teacher in the classroom or in the school yard, can help a child who has dissociated to reorient to the class or the school ground. You can also work together with the child to minimise dissociative experiences in the future. Helpful responses when a child dissociates include:

- Reassuring the child that they are safe (remember dissociative behaviours stem from fear, rage, shame, helplessness, loss, confusion, and other difficult feelings; not wilful manipulation or laziness).

- Responding empathically (e.g., “You look scared, I’m sorry the siren scared you”).

- Suspending confrontation until a child is more present.

- Allowing the child to quietly go to a ‘designated safe space’ within the classroom (e.g., reading corner or a spare table).

- Accepting the child’s feelings even if they do not make sense to you by letting the child know that all his feelings are accepted by you (even if you don’t understand why the child is responding the way he is at a given situation).

- Encouraging the child to utilise more appropriate ways to express difficult feelings (for example, scribble or draw, put feelings into words in a journal, squeeze a squeeze-ball, go for a run in the gym or engage in some other physical activity which safely discharges intense feelings) Avoiding telling or asking for the ‘positive part’ of the child Allowing the child to visit the counsellor or sit in the principal’s office to calm down, and calling the supportive caregiver.

- Presenting consequences for undesirable behaviour only after the child has calmed down.

Helpful responses for working with a child at a time when the dissociation is not happening and to decreasing the child’s need to dissociate include:

- Developing a cue word with the dissociative child that can be used to bring the child back to the present.

- Developing agreed upon hand signals to use in front of the child to warn them that they’re drifting off in order to bring them back to the here and now.

- Learning to recognise, and when possible eliminate, the triggers (i.e., unexpected touch, harsh voice) that cause the child to dissociate.

- Letting the child know ahead of time when a trigger is unavoidable (e.g., if leaving the classroom results in aggressive or immature behaviour, it can help to remind the child of an upcoming transition before the class is to leave, and reassure them they are safe).

- Letting the child have a safe-object in their desk to help him ‘pull it together’ if they are feeling overwhelmed (often times simply knowing the option is available already helps the child feel safer and feeling safer reduces the need to dissociate).

- Limiting surprises.

- Creating a predictable routine.

- Pairing the child with a supportive, caring peer for activities which raise the child’s anxiety (e.g., class trip, recess, a trip to the bathroom).

- Playing music the child associates with safely.

- While these responses may seem at first glance as ‘coddling’ or ‘rewarding bad behaviour,’ they will help the child reorient to the present situation faster, handle themselves better in the classroom, and accept responsibility for their behaviour.

While these steps may seem time consuming, they need not take much time, in that they can deescalate, rather than escalate, a problem, they may save you time. In addition, they often take even less time as the ‘routine’ becomes more familiar (to both of you) and the child learns to associate your voice and words with reorienting.

You may worry that such ‘coddling’ may make it worth it for the child to act out in order to get that special attention. With dissociation, however; these phrases have a different effect—they increase safety and thus help the child not to become overwhelmed and need to dissociate. This will most likely serve to reassure the child that you care, that they are safe with you and can trust you to help them when they feel overwhelmed, agitated, shut down or ‘spaced out’.

You may worry that other children in the class will resent the ‘special treatment’ that the child will be getting. However (and especially if a child is aggressive or explosive), classmates often welcome less drama and a calmer classroom. Moreover, classmates often follow the teacher’s modelling of offering support and compassion if the child gets upset.

Classroom intervention cannot and should not take the place of specialised assessment by a professional knowledgeable in the area of trauma and dissociation (and, if needed, trauma treatment where the child can be helped to deal with the issues that underlie the dissociation). Nonetheless, simple steps can assist both you and the child in feeling more in control, and can help make school experience a safer one for the child.

Questions for consideration

Three questions about the student’s resources:

- In what situations is the young person most likely to be able to maintain themselves within their window of tolerance and thus utilise social engagement with others and feel safe?

- Are there particular people that the student feels most safe with?

- In what situations are the young person’s protective responses most likely to be shown?

Five questions to take into the classroom with you:

- Where is the young person in relation to their window of tolerance?

- How do I know?

- Where am I in relation to my window of tolerance?

- How do I know?

- What do I need right now to maintain myself in my window of tolerance?

Three questions to share with colleagues:

- What are some ways to share knowledge about the window of tolerance framework amongst teachers and students?

- What are some strategies you already use to help students maintain themselves within their windows of tolerance?

- What are some things you do to maintain yourselves within your windows of tolerance?

Reflective questions

- Name the three ways in which trauma impacts the brain.

- What are the five zones of the ‘window of tolerance’ model?

- How can teachers help student who are dissociative?

![]()

Additional reading

Read the following: Tobin, M. (2016). Childhood trauma: Developmental pathways and implications for the classroom. Changing Minds: Discussions in Neuroscience, Psychology and Education, 3, 1-19. Australian Council for Educational Research.