5.1 Social-emotional competence

True story

“Teach him how to be a little boy at school,” was the request from the Senior Guidance Officer as she stood at the Intervention Centre door with Elliott. The Intervention Centre was for students who had been suspended or excluded from school. It was a temporary placement for behaviour intervention and support to reintegrate the student back into the school environment. Most students were at the Intervention Centre for 8-10 weeks, some longer. “He has had a rough little life and just needs someone to play with him and help him learn what it is to be a child. Next time he is violent the school will exclude him” she continued.

Elliott and I went to play on the carpet and I rolled out the car mat between us and handed Elliott a toy car. He looked at it, turned it over, looked back at me and waited. He had no idea what to do with it. I placed my car on the road and made “broom, broom” noises. Elliott just watched, holding his car tightly in his hand.

And so it went like this for many days. I played, narrating what I was doing and feeling and Elliott watched. At the end of two weeks, he bravely put his car onto the mat and mimicked “broom, broom.” It was like Christmas. I was thrilled.

Elliott was eight years old. He had lived in a series of foster care situations since he was two years old. Removed from his home due to severe neglect and abuse, Elliott had no concept of caring or compassion but he was learning ever so slowly how to be a little boy and that is why his eight week stay at the Intervention Centre became a year.

Social-emotional competence

Competence in social emotional learning is recognised as having a significant influence on a child’s school readiness, school adjustment and academic achievement (Beamish & Saggers, 2014). Supporting the social emotional health of children is integral to teaching. Social emotional learnings develop resilience in children and foster positive wellbeing. The Collaborative for Academic, Social and Emotional Learning (CASEL) is a leader in the field of social emotional learning. Formed in 1994, this group of American educators, child advocates and researchers, introduced the term social and emotional learning. CASEL (2020, para. 1) define social and emotional learning in the following way: “Social and emotional learning (SEL) is the process through which children and adults acquire and effectively apply the knowledge, attitudes, and skills necessary to understand and manage emotions, set and achieve positive goals, feel and show empathy for others, establish and maintain positive relationships, and make responsible decisions.”

It all begins in early childhood, the tone is set, the path laid out and the future sketched. So much that happens in the early years significantly impacts future quality of life. Being ready for school, functioning effectively at school, interacting positively with people at school and being academically successful at school, are governed by social-emotional competence (Bailey, Denham, Curby, & Bassett, 2016; Bayat, 2015; Denham, 2010). Generally speaking, emotional competence is about understanding feelings and social competence is about effective interactions and relationships. Relationships – secure, safe and attached. While recognising that each child is unique and will have needs original to themselves, we will begin with evidence-based strategies known to be helpful for all children with trauma.

Key factors to support social-emotional competence

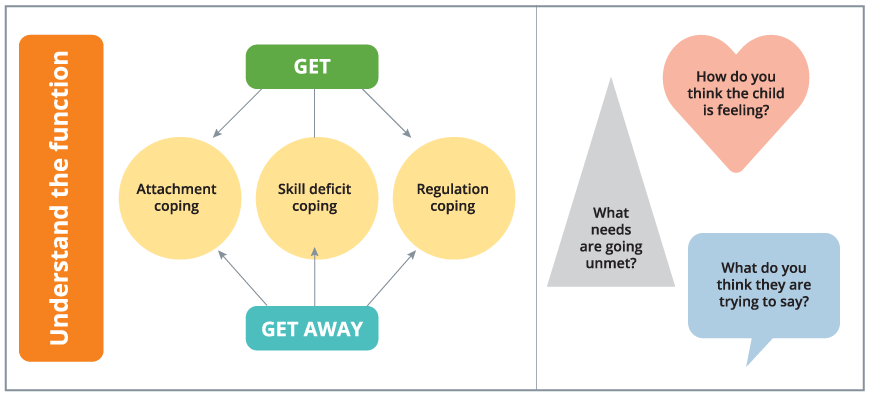

Learning, relationships and emotions go hand in hand. Without the capacity to navigate the social world of school with a firm grasp on emotions, learning becomes problematic. Experiences teach skills and if an experience is repeated, the skill or skills associated with it, together with the response, become imprinted in the brain. For the child with trauma there is often a mismatch between highly developed responses e.g., for survival and underdeveloped responses needed for school success (Blaustein, 2013).

At the core of helping children with trauma develop their social-emotional competencies is teaching new behaviours. For those children who have not had the opportunity of experiencing quality attachment and having care and considerate behaviours modelled to them, behaving in a socially appropriate manner eludes them as it has not been part of their life and therefore, they have little to no experience of it. New behaviours that are an appropriate means of communication that get the child what they want in a manner that is acceptable in the space or environment and acceptable to, the people within it, need to be explicitly planned and taught. These behaviours are what behaviourists call replacement (or alternative) behaviours. In addition to learning new behaviours naming emotions is critical to developing emotional competence and self-regulation. Naming emotions is the first step to coping with them, so it is important that the child with trauma develops a vocabulary to name their feelings (Hertel & Johnson, 2013).

A key component of social-emotional competence are social skills. As with teaching behaviour, these need to be intentionally planned and taught with the purpose of the skill clearly explained to the child. Skills such as turn taking, sharing, joining in and problem solving are essential skills for the child to master so that they can participate to the best of their ability within the learning environment and establish friendships through positive interactions with their peers. Broken attachments, lacking social skills, difficulties regulating emotions and establishing relationships, the child with trauma needs support to learn and grow. From the foundation that all learning is relationships, the teacher is kind, flexible and attuned to the student’s unique needs, building trusting spaces for learning and helping the student with trauma build regulation skills through modelling, teaching and listening.

With reference to “positive replacement behaviours” (Gresham, 2015, p. 199), Gresham makes the clear distinction between social skills, social tasks, and social competence. Social skills are the explicit behaviours that a child demonstrates that are needed to complete a social task. Social tasks are things like making friends, joining in and playing games. Social competence is the ability of the child to demonstrate a social task successfully as judged by another (a teacher, peer, parent) against a set of criteria (Gresham, 2015, p. 199) and therefore in the demonstration of that social task show a degree of competency in executing the social skill or skills needed for that social task.

The upcoming sections focuses more broadly on social-emotional competence in relation to the period of a individual’s life.

Five keys to social and emotional learning

Five keys to social and emotional learning

[6 mins 2 secs]

Watch this short video on the five keys to successful social and emotional learning. Choose one of the keys and think about what this would look like for the child with trauma in your context.

A transcript and Closed Captions are also available within the video.

References

Bailey, C. S., Denham, S. A., Curby, T. W., & Bassett, H. H. (2016). Emotional and organizational supports for preschoolers’ emotion regulation: Relations with school adjustment. Emotion, 16(2), 263-279.

Bayat, M. (2015). Addressing challenging behaviors and mental health issues in early childhood. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis.

Blaustein, M. E. (2013). Childhood trauma and a framework for intervention. In E. Rossen & R. Hull (Eds.), Supporting and educating traumatized students. A guide for school-based professionals (pp. 3-21). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Beamish, W., & Saggers, B. (2014). Strengthening social and emotional learning in children with special needs. In S. Garvis & D. Pendergast (Eds.), Health and Wellbeing in Childhood. Cambridge University Press.

Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning. (2020). What is SEL? Retrieved from https://casel.org/what-is-sel/.

Denham, S. A. (2010). Social-emotional competence as support for school readiness: What is it and how do we assess it? Early Education and Development, 17(1), 57-89. doi:10.1207/s15566935eed1701_4.

Gresham, F. M. (2015). Disruptive behavior disorders. Evidence-based practice for assessment and intervention. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Hertel, R., & Johnson, M. M. (2013). How the traumatic experiences of students manifest in school settings. In E. Rossen & R. Hull (Eds.), Supporting and educating traumatized students. A guide for school-based professionals (pp. 23-35). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.