6.3 We’re all in this together: impact of secondary trauma on organisations

Secondary stress is a health and safety issue for schools. Schools need to recognise it as a potential hazard for carers and staff. Risk assessment requires that schools assess the possible risks that could arise from hazards and daily stressors. They must also have strategies to reduce and manage the sources of stress for teachers and support staff in schools. Managers and supervisors need to understand why secondary stress could affect people’s ability to care for foster children or perform to their usual standard at work. They also need to recognise the benefits of the school having strategies to prevent and support staff in seeking treatment for secondary stress. It’s important that such action do not depend on one or two interested individuals, but be incorporated into the whole organisation’s policies and procedures.

Impact of traumatic stress on schools

To understand the impact of traumatic stress on organisations, it is useful to review our understanding of the impact of trauma on children. As seen in the previous chapters, children who are exposed to violence and other forms of traumatic experience, including neglect – particularly if these stressors are recurrent or chronic – may respond with a complex variety of problems. They are unable to keep themselves safe in the world and often put other people at risk for harm as well. They are chronically tense and hyper-aroused with hair-trigger tempers and a compromised ability to manage distressing emotions. This emotional arousal interferes with the development of good decision-making, problem solving skills and conflict resolution skills and as a result, the ability to communicate constructively with others does not develop properly. This results in grave cognitive, emotional and interpersonal difficulties.

As a consequence, self-correcting skills that involve self-control and self-discipline fail to develop properly. Breaches of trust that are a result of failed interpersonal relationships lead to problems with trusting or constructively collaborating with authority figures. These failures lead to a progressive lack of integration among the various cognitive, emotional, and interpersonal functions required of human beings in complex societies. This lack of integration produces basic deficits that result in demoralisation, loss of faith, helplessness, hopelessness, the loss of meaning and purpose and the spiralling degradation of repetition and avoidance. Lacking the necessary skills to deal with overwhelming emotions, young people frequently resort to substances, behaviours, and destructive relationships that will help them avoid the shame of failure, the anger of unjust treatment, and the grief of recurrent loss. Parallel difficulties may be found in organisations that attempt to serve these individuals.

Today, organisations like schools are experiencing significant stress. In many schools, neither the staff nor the administrators feel particularly safe with their clients or even with each other. Atmospheres of recurrent or constant crisis severely constrain the ability of staff to constructively confront problems, engage in complex problem-solving, and involve all levels of staff in decision making processes. Communication networks tend to break down under stress and as this occurs, service delivery becomes increasingly fragmented. When communication networks break down so too do the feedback loops that are necessary for consistent and timely error correction. As decision-making becomes increasingly non-participatory and problem solving more reactive, an increasing number of short-sighted policy decisions are made that appear to compound existing problems.

Unresolved interpersonal conflicts increase and are not resolved. As the situation feels increasingly out of control, organisational leaders become more controlling, instituting ever more punitive measures in an attempt to forestall chaos. Staff respond to the perceived punitive measures instituted by leaders through acting-out and passive-aggressive behaviours. As the organisation becomes more hierarchical there is a progressive and simultaneous isolation of leaders and a ‘dumbing down’ of staff. Over time, leaders and staff lose sight of the essential purpose of their work together and derive less and less satisfaction and meaning from the work. Standards of care deteriorate, and quality assurance standards are lowered in an attempt to deny or hide this deterioration. When this spiral is occurring, staff feel increasingly angry, demoralised, ‘burned out,’ helpless and hopeless about the people they are working to serve. Ultimately, if this deadly sequence is not arrested, the organisation begins to look and act in uncannily similar ways to the traumatised clients it is supposed to be helping.

Parallel processes

The concept of parallel processes is a useful way of offering a coherent framework that can enable staff and leaders to develop a way of thinking ‘outside the box’ about what has happened and is happening to their service delivery systems, based on an understanding of the ways in which trauma and chronic adversity affect human functioning. Smith et al. (1989) describe parallel processes as occurring when two or more systems – whether these consist of individuals, groups or organisations – having a significant relationship with one another. When this occurs, these systems tend to develop similar affects, cognitions and behaviours, which are defined as parallel processes. Parallel processes can be set in motion in many ways, and once initiated leave no one immune from their influence.

Students bring their past history of traumatic experiences into schools, consciously aware of some of their challenges but unconsciously struggling to recover from the pain and loss of their past. They are greeted by well-meaning teachers, subject to their own personal life experiences, who are more or less deeply embedded in entire systems that are under significantly stress. Given what we know about exposure to childhood adversity and other forms of traumatic experience, the majority of teachers and educational staff have experiences in their background and that similarity may be more or less recognised and at varying levels of resolution (Felitti et al., 1998). The result of these complex interactions between the traumatised students, stressed teachers, pressured schools, and a social and economic environment that is frequently hostile to the aims of recovery and support is often the opposite of what was intended. Teachers in schools of high rates of behavioural difficulties suffer both physical and psychological injuries and thus become demoralised and hostile. Their counter-aggressive responses to the aggression of the students help to create a culture of punitive responses.

Leaders become variously perplexed, overwhelmed, ineffective, authoritarian or avoidant as they struggle to satisfy the demands of their superiors, to control their staff and to protect their students. When educational staff and other support staff gather together in an attempt to create an approach to complex problems, they are often not on the same page. They share no common framework that forms the basis to their problem-solving. Without a shared way of understanding the problem, what passes as support may be little more than labelling and punitive or insufficiently thought out behaviour management approaches. When troubled students fail to engage or respond to these strategies, they are labelled again, given more warnings and consequences and termed ‘too difficult’ or ‘too damaged’ to engage in a school environment.

In this way, our school systems inadvertently but frequently recapitulate the experiences that have proved so toxic for children we are supposed to help. Just as the lives of children exposed to repetitive and chronic trauma, abuse and maltreatment become organised around the traumatic experiences, so too can entire systems become organised around the recurrent and severe stress of trying to cope with a flawed mental model based on individual deficits and diagnoses, which is the present underpinnings of our educational systems. When this happens, it sets up an interactive dynamic that creates what are sometimes uncannily similar processes at various levels of organisations and departments. Trauma theory brings context back to educational institutions, while integrating the importance of the biological discoveries of the last several decades. There are currently significant efforts directed at helping schools become trauma informed. In the following section we describe a framework put forward by Sandra Bloom (2010) for school staff and leaders to become more sensitive to the ways in which individuals and groups of people exposed to overwhelming stress can be supported.

Safety

Schools and classrooms can become an unsafe – physically and emotionally – for students and teachers. This can happen either through teachers having to manage physical and verbal aggression of students or by the management of risky behaviours such as self-harm or sexualised behaviours from students. When this occurs, the basic trust that supports complex problem solving and high productivity is eroded. The list of behaviours that can trigger mistrust in staff is a long one and includes both verbal and nonverbal behaviour: silence, glaring eye contact, abruptness, snubbing, insults, public humiliation, blaming, discrediting, aggressive and controlling behaviour, overtly threatening behaviour, yelling and shouting, public humiliation, angry outbursts, secretive decision making, indirect communication, lack of responsiveness to input, mixed messages aloofness, unethical conduct – all can be experienced as abusive managerial or supervisory behaviour (Ryan & Oestreich, 1998). According to Bill Wilkerson, CEO of Global Business and Economic Roundtable on Addiction and Mental Health, “mistrust, unfairness and vicious office politics” are among the top ten workplace stressors (Collie, 2004).

Emotional control

Pekrun and Frese (1992) have argued that emotions are among the primary determinants of behaviour at work. Emotion can profoundly influence both social climate and the productivity of companies and organisations. Under normal conditions, a school manages and contains the emotional contagion that is an inevitable part of functioning within groups of human beings. This is done through normal problem-solving, decision making, and conflict resolution methods and school policies and procedures that must exist for any school to operate effectively. These are the norms that enable groups of teachers and students to tolerate the normal amount of anxiety that exists among people working on a task, tolerate uncertainty long enough for creative problem solutions to emerge, promote balanced and integrated decision making so that all essential points of view are synthesised, contain and resolve the inevitable conflicts that arise between members of a group and complete its tasks (Bloom, 2004).

In organisations under chronic, relentless stress, however, this healthier level of function is likely sacrificed in service of facing repetitive emergency situations and entire organisations may begin to look like highly stressed individuals. Traumatised people often develop chronic hyperarousal as the central nervous system adapts to the constancy of threat. Similarly, schools may become chronically hyper-aroused, so that everything becomes a crisis. When this happens, the capacity to prioritise what is important and what can be postponed is lost. Stress levels universally increase for everyone and, as one principal has said, “it’s like managing with your hair on fire”. Under conditions of chronic crisis, emotional distress escalates, tempers become short, decision making becomes impaired and driven by impulse, while pressures to conform reduce individual and group effectiveness (Ryan & Oestreich, 1998).

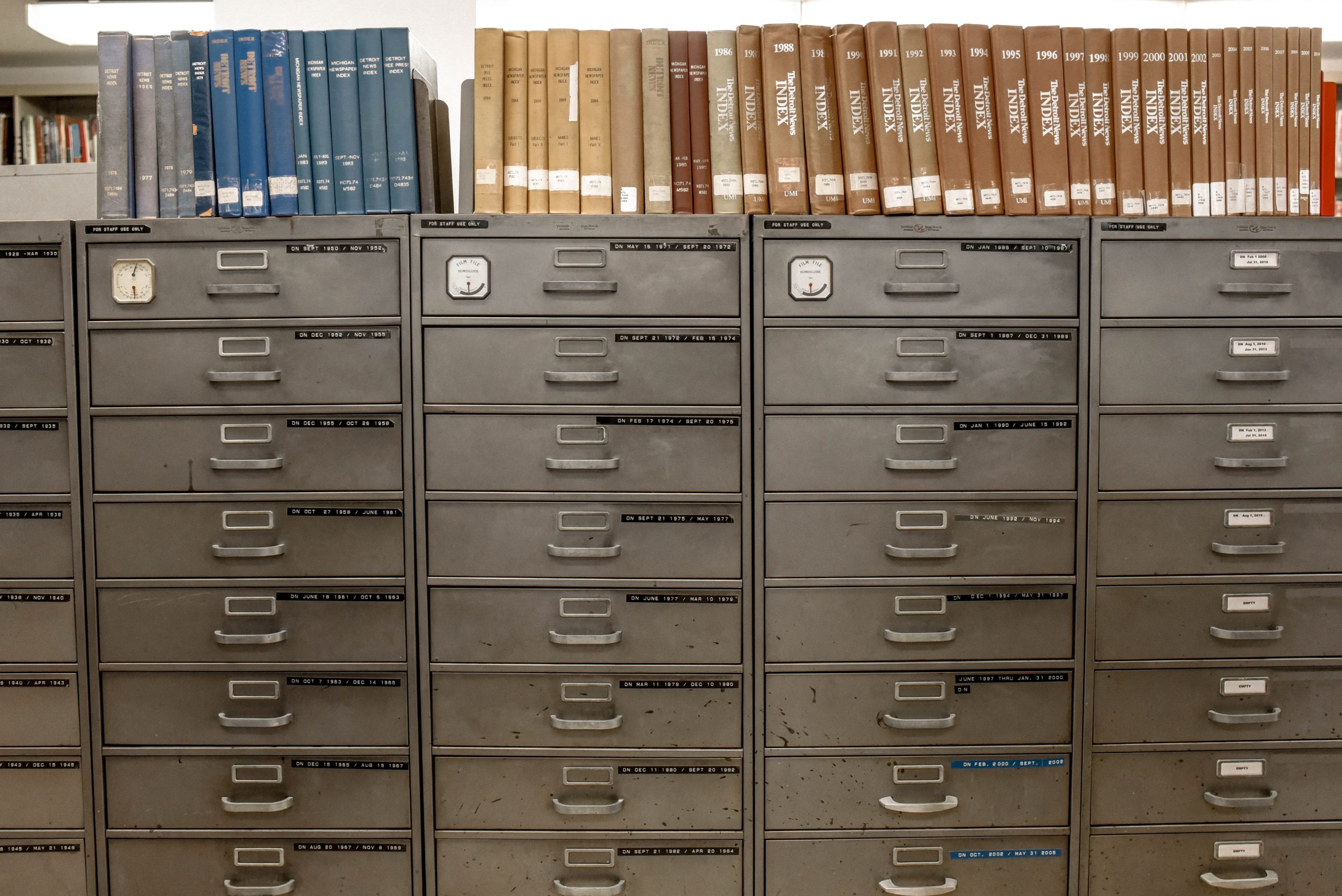

Organisational amnesia

Just like individuals, if they are to learn, schools must have memory. Some modern philosophers believe that all memories are formed and organised within a collective context (Halbwachs, 1992). Organisational memory refers to stored information from an organisation’s history that can be brought to bear on present decisions. Knowledge about the history of a school or educational department, like individual knowledge, exists in two basic forms: explicit knowledge, which is easily codified and shared asynchronously; and tacit knowledge, which is experiential, intuitive and communicated most effectively in face-to-face encounters. Explicit knowledge can be articulated within formal language. It is that which can be recorded and stored in the more concrete organisational storage bins: records, policies and procedure manuals, training curriculums, orientation programs, organisational structures and links of authority, and other written and promotional materials (Weick, 1979).

Tacit knowledge is that knowledge which is used to interpret the information – knowledge that is more difficult to articulate with language but lies in the values, beliefs and priorities of an organisation (Lahaie, 2005; Othman & Hashim, 2004). Tacit knowledge resides within the individual memories of every person who is or has ever been a part of the organisation is cumulative, slow to diffuse, is rooted in the human beings who comprise the organisation, and create the organisation’s culture. Every teacher who leaves a school takes a part of the school’s memory with them. As a result, over time and with sufficient loss, the educational institutions develop what’s referred to as ‘organisational amnesia’ that affects learning and adaptation of the staff to the demands imposed on them (Kransdorff, 1998). Organisational amnesia becomes a tangible problem to be managed when there is a loss of collective experience and accumulated skills through the trauma of excessive downsizing, layoffs or people choosing to leave an organisation.

The result of organisational amnesia may be a deafening silence about vital but troubling information, not dissimilar to the deafening silence that surrounds family secrets such as incest, or domestic violence. There is reason to believe that maintaining silence about disturbing collective events may have the counter-effect of making the memory even more potent in its continuing influence on the individuals within the organisation as well as the organisation as a whole, much as silent traumatic memories continue to haunt traumatised individuals and families.

Communication

Under increasing levels of organisation stress, the vital communication that is the lifeblood of an organisation starts to break down. As stress increases, perceptions of staff narrow, and the consideration of contextual information is lost and circumstances relating to staff working together as a group deteriorates to more extreme levels before they are noticed. All of this leads to more puzzlement – both among staff, school leaders and higher-level administrators.

Communication is necessary to detect errors and oversights, and risky situations and crises tend to create the need for processes by which information is communicated from teachers in the classroom to the school leaders within educational institutions. These pathways of communication – to and from the school leaders – that is often compromised and become are of poor quality when under stress or pressure. Without such communication, staff and the school community are not provided with appropriate feedback and do not learn or know how to function better into the future. Research has shown that organisations are exceedingly complex systems that can easily drift toward disaster, unless they maintain resources that enable them to learn from unusual events in their day-to-day functioning (Marcus & Nichols, 1999).

Organisations that already have poor communication structures are more likely to handle crises poorly (Kanter & Stein, 1992). Instead of increasing impersonal communications, staff in crisis are likely to resort to the excessive use of one-way forms of communication. Under stress, the staff in supervisory and leadership positions in organisation tend to focus on the delivery of top-down information flow – largely characterised by new policies, procedures and processes intended to control what staff and student can and can’t do. Feedback loops – pathways for how information is communicated between members of a group – erode under such circumstances of stress and morale starts to decline as the initiatives and work requirements that are communicated do not alleviate the stress or successfully resolve the problems faced by the teachers.

Authoritarianism

When danger is real and present, effective leaders take charge and give commands that are obeyed by obedient staff, thus harnessing and directing the combined power of many individuals in service of helping the institution excel, be continued to be funded and supported into the future. When a crisis occurs, the ‘centralisation of control’ is significantly increased, with leaders tightening reins, concentrating power at the top and minimising participatory decision making – seeking the thoughts and opinions of staff less and less when making decisions (Kanter & Stein, 1992). This is referred to as an authoritarian style of leadership. Even where there are strong beliefs in the democratic way of life, there is always a tendency in institutions like schools, and in the wider society, to regress to simple, hierarchical models of authority as a way of preserving a sense of security and stability. It’s important to note that this is not just a phenomenon of leadership – in times of great uncertainty, everyone in institutions colludes to collectively bring into being authoritarian organisations, as a time-honoured method for providing at least the illusion of greater certainty, predictability and therefore reducing anxiety amongst staff (Lawrence, 2015).

However, when a state of crisis or situations of heightened risk are prolonged, repetitive or chronic, there is a price to be paid. The tendency to develop increasingly authoritarian ways of working in institutions is particularly troublesome for organisations like schools. A chronically high level of stress results in a school climate that promotes authoritarian behaviour and this behaviour serves to reinforce existing hierarchies and create new ones. Communication exchanges become more formalised and a one-way street – from leaders down to staff and not the other way around. Command hierarchies become less flexible, power becomes more centralised, staff on the ground stop talking openly and, as a result, important information is lost from the system (Weick, 2001).

The centralisation of authority means that those at the top of a hierarchy will be far more influential than those at the bottom, and yet better solutions to the existing problems may actually lie in the hands of those with less authority. Authoritarian leadership is likely to encourage the same leadership style throughout the organisation. The loss of democratic processes results in oversimplified decision making and the loss of empowerment at each organisational level reduces morale and increases interpersonal conflict. As a result, the organisational norms of the behaviour of all staff are likely to support punitive and exclusionary consequences and failures in being empathetic when managing difficult situations. When such authoritarian behaviour goes unchecked, staff members can become bullies.

Silencing of dissent

The greater the authoritarian pressures in an organisation and the greater the chronic stress, the greater is the likelihood that strenuous attempts will be made to silence those who might disagree with the decisions and choices being made in these institutions. Empirical data show that ‘organisational silence’ emerges out of staff members’ fear to speak up about issues or problems they encounter at work (Morrison & Milliken, 2000). These underground topics become the ‘unspeakable’ topics become the undiscussables in an organisation, covering a wide range of areas, including decision-making, procedures, managerial incompetence, pay inequity, organisational inefficiencies and poor organisational performance (Ryan & Oestreich, 1998). Dissent is even less welcome in organisations characterised by chronic stress when dissent is seen as a threat to the staff needing to act in a unified manner. As a result, the quality of how problems are analysed, and decisions made deteriorates. If this cycle is not stopped and the organisation allowed opportunity to recuperate, the result may be an organisation that becomes destructive – similar to how severe traumatised children behave (Bloom, 2004).

Decision-making and conflict management

As systemic stress increases, and authority becomes more centralised, organisational decision-making processes are likely to deteriorate, becoming less complex, more driven by impulse, with a narrowing focus and attention only to immediate threat. Long term consequences of decisions may not be considered, and alternatives remain unexplored (Janis, 1982). As work-related stressors increase, staff develop negative perceptions of their co-workers, and organisational leaders and this may precipitate serious decreases in job performance. Conflict over the tasks needing to be completed can be useful, but emotion inevitably accompanies such conflict in stressed organisations. Without good conflict management skills in the staff group, tasks-related to conflict can lead to even more misunderstanding, miscommunication, and increased team dysfunction, instead of providing the kind of enriching conversations that can lead to creative problem solving. Over time, it becomes apparent that people in the staffing group do not like and respect each other and spend their time in personal conflicts, while the group as a whole performs badly. Chronic stress puts an added burden on old conflicts, which are likely to emerge and propagate new conflicts.

Hierarchical structures concentrate power and, in these circumstances, power can easily come to be used abusively and in a way that perpetuates rather than attenuates the concentration of power. Transparency disappears, and secrecy increases under this influence – staff members are left feeling uncertain about changes within the organisation. Communication networks become compromised as those in power become more punitive, and the likelihood of errors being made increases as a result. In such situations, conflicts tend to not be addressed and remain unresolved, tensions and resentment mount under the surface of daily interactions between staff and between staff and students.

Disempowerment and learned helplessness

Learned helplessness in workplaces has been defined as a debilitating cognitive state in which individuals often possess the skills and abilities necessary to perform their jobs, but exhibit suboptimal or poor performance because they attribute prior failures to causes which they cannot change, even though success may be possible in the current environment (Campbell & Martinko, 1998). In controlling, non-participatory work environments, every subsequent lower level of employee is likely to become progressively disempowered. After years, decades and even generations of controlling management styles, reversing this sense of disempowerment can be very difficult, particularly under conditions of chronic, unrelenting organisational stress. Helpless to protect themselves, feeling embattled, hopeless and helpless, the staff and management often engage in ‘risk avoidance’ behaviours where risk management policies prevent health change, adaptation, creativity and innovation.

Increased aggression

The most feared form of workplace aggression is physical violence, but there are several other forms of aggression that can be seen in the workplace. These can take the forms of dirty looks, stealing, hiding needed resources, threats and insults, ignoring input, unfair performance appraisals, spreading rumours, intentionally arriving late to meetings, failing to pass on information and failing to warn of potential danger. All of these actions on the part of management, staff and students are subtle forms of aggression. Stressful times are difficult for employees and as interpersonal conflict increases, it is likely that workers will express their anger, frustration and resentment in a variety of way that have a negative effect on work performance. Frequently, bureaucracy is substituted for participatory agreement on necessary changes, and the more an organisation grows in size and complexity, the more likely this is to happen (Huberman, 1964). Research has demonstrated that poorer the performance gets, the more punitive leaders become, and that very possibly just when leaders need to be instituting positive reinforcing behaviours to promote positive change, they instead become increasingly controlling and punishing (Sims, 1980). A sure sign of an increase in aggression in the workplace is an escalation of vicious gossip and unsubstantiated rumour. Research shows that 70% of all organisational communication comes through this system of informal communication, and several national surveys have found that employees used ‘the grapevine’ as a communication source more than any other vehicle of communication (Crampton et al., 1998). Not only that, but the grapevine has been shown to communicate information far more rapidly than formal systems of communication. All of this lends itself to the promotion of a toxic environment.

Unresolved grief, re-enactment and organisational decline

Losses to the organisation are likely to be experienced individually as well as collectively (Carr, 2001). For the same reason, failure of the organisation to live up to whatever internalised ideal the individual has for the way that the organisation should function are likely to be experienced individually and collectively as a betrayal of trust, a loss of certainty and security, a disheartening collapse of meaning and purpose. Sudden departures of key leaders, the sudden death of a fellow teacher or loss of colleagues due to downsizing can be experienced as organisationally traumatic. It is clear that the ways in which grief, loss and termination are handled have a significant impact on employee attitudes. Unresolved grief can result in an idealisation of what has been lost that interferes with adaptation to a new reality. The failure to grieve for the loss of a leader may make it difficult or impossible for a new leader to be accepted by the group.

Traumatised individuals are frequently subject to traumatic re-enactments – a compulsive reliving of a traumatic past that is not recognised as repetitive and yet, which frequently leads to re-victimisation experiences. Such ‘re-enactment’ is a sign of grief that is not resolved. An organisation that cannot change, that cannot work through loss and move on, is likely to develop patterns of re-enactment, repeating past failed strategies without recognising that these strategies may no longer be effective. This can easily lead to organisational patterns that become overtly abusive. The rigid repetition of the past and the inability to adapt to change may lead to organisational decline and possibly dissolution. All of these behaviours can be seen as inhibitors of organisational learning and adaptation.

Organisational change is always challenging, and all too frequently fails (Pascale et al., 2000). But constant and rapid adaptation to a rapidly changing environment becomes a basic necessity for organisational survival. In supporting traumatised students, survivors of traumatic life events and sustained adversity, it has become clear that having a different way to assess and understand past and current problems is frequently the beginning of a healing and event transformative process. If teachers of a trauma informed school can similarly adopt a trauma informed mindset and approach to working, that enables them to collectively assess and constructively respond to recurrent stress in a different way, transformative, sustainable, and inclusive organisational change may be possible.

‘Creating sanctuary in the classroom’ by Sandra Bloom

‘Creating sanctuary in the classroom’ by Sandra Bloom outlines trauma-informed processes and strategies for educators.

The Staffroom [27 mins]

Watch episode one of ‘The Staffroom’ – a three-part documentary as part of the ABC’s Compass program. The show explores the demands and pressures of being a teacher in Australian public schools. Please note that the clip contains themes and images that may be distressing to some. Please feel free to stop watching the video if you are distressed.

References

Bloom, S. L. (2004). Neither liberty nor safety: the impact of trauma on individuals, institutions, and societies. Part I. Psychotherapy and Politics International, 2, 78-98.

Bloom, S. (2010). Trauma-organized systems and parallel process. In N. Tehrani (Ed). Managing Trauma in the Workplace – Supporting Workers and the Organisation (pp. 139-153). London: Routledge.

Campbell, C. R., & Martinko, M. J. (1998) An integrative attributional perspective of empowerment and learned helplessness: a multimethod field study. Journal of Management, 24, 173-200.

Carr, A. (2001) Understanding emotion and emotionality in a process of change. Journal of Organisational Change Management, 14, 421-434.

Collie, D. (2004). Workplace stress: Expensive stuff. Retrieved from http://www.emaxhealth.com/38/473.html.

Crampton, S. M., Hodge, J. W., & Mishra, J. M. (1998) The informal communication network: factors influencing the grapevine activity. Public Personnel Management, 27, 569.

Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V. E…Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults. The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventative Medicine, 14(4), 245‐58.

Halbwachs, M. (1992). On collective memory (Edited, Translated and Introduced by Lewis A Coser). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Huberman, J. (1964) Discipline without punishment. Harvard Business Review, 42, 62-68.

Janis, I. L. (1982). Groupthink: Psychological studies of policy decisions and fiascos. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Kanter, R. M., & Stein B. A. (1992). The challenge of organisational change: How companies experience it and leaders guide it. New York: Free Press.

Kransdorff, A. (1998). Corporate amnesia: Keeping know-how in the company. Butterworth Heinemann.

Lahaie, D. (2005). The impact of corporate memory loss: What happens when a senior executive leaves? International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance Incorporating Leadership in Health Services. doi: 10.1108/13660750510611198.

Lawrence, D., Johnson, S., Hafekost, J., Boterhoven de Haan, K., Sawyer, M., Ainley, J., & Zubrick, S. R. (2015). The mental health of children and adolescents: Report on the second Australian child and adolescent survey of mental health and wellbeing.

Marcus, A. A., & Nichols, M. L. (1999). On the edge: heeding the warnings of unusual events. Organisation Science: A Journal of the Institute of Management Sciences, 10, 482.

Morrison, E. W., & Miliken, F. J. (2000). Organisational silence: a barrier to change and development in pluralistic world. Academy of Management Review, 25, 706.

Othman, R. and Hashim, N.A. (2004). Typologising organisational amnesia. The Learning Organisation, 11(3), 273-84.

Pascale, R. T., Millimanm, M., & Gioka, L. (2000). Surfing the edge of chaos: The laws of nature and the new laws of business. New York: Crown Business.

Pekrun, R., & Frese, M. (1992). Emotions in work and achievement. International Review of Industrial and Organisational Psychology, 7, 153-200.

Ryan, K., & Oestreich, D. K. (1998). Driving fear out of the workplace: Creating the high-trust, high-performance organization. Jossey-Bass.

Sims, H. P. Jr (1980). Further thoughts on punishment in organisations. Academy of Management Review, 5, 133.

Smith, K. K., Simmons, V. A., & Thames, T. B. (1989). “Fix the Women”: An intervention into an organisational conflict based on parallel process thinking. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 25(1), 11‐29.

Weick, K. E. (1979). The social psychology of organising. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.