1.1 Childhood adversity and maltreatment

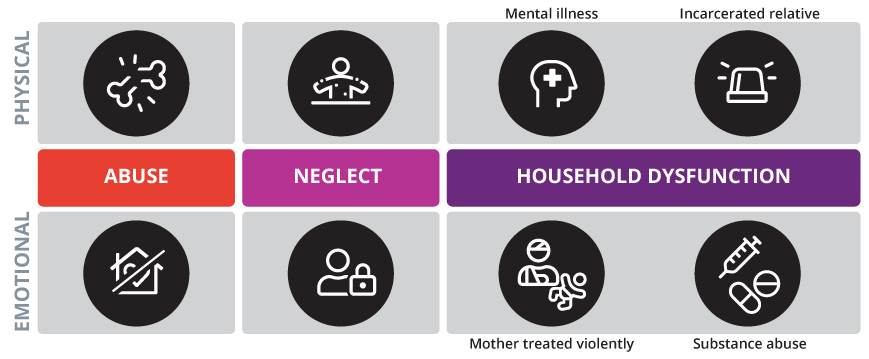

Child maltreatment refers to any non-accidental behaviour by parents, caregivers, other adults or older adolescents that are outside the norms of conduct and entail a substantial risk of causing physical or emotional harm to a child or young person. Such behaviours may be intentional or unintentional and can include acts of omission (i.e., neglect) and commission (i.e., abuse) (Bromfield, 2005; Christoffel et al., 1992).

Child maltreatment is commonly divided into five main subtypes:

- physical abuse

- emotional maltreatment

- neglect

- sexual abuse and

- exposure to family violence

Although there is a broad consensus regarding the different subtypes of maltreatment, disagreement exists about exactly how to define these subtypes. In the absence of universal definitions of child abuse and neglect, different professional fields have developed their own definitions. There are medical and clinical definitions, social service definitions, legal and judicial definitions, and research definitions of child maltreatment. Each professional sector tends to emphasise the facets of maltreatment that are most salient to their own field. For example, medical definitions highlight the physical symptoms of a child rather than the abusive or neglectful behaviours of a perpetrator, while legal and judicial definitions focus on those aspects of parental behaviour and mental health symptoms that provide the best evidence for a successful prosecution (Bromfield, 2005; Feerick, Knutson, Trickett, & Flanzer, 2006).

ReMOVED [12 mins 46 secs]

Watch this short video to understand the impact of child maltreatment on children in child welfare. Please note that the clip contains themes and images that may be distressing to some. Please feel free to stop watching the video if you are distressed.

A transcript and Closed Captions are also available within the video.

A number of complex issues need to be considered when trying to define a form of maltreatment. For example:

- Definitions of child maltreatment reflect cultural values and beliefs. Behaviour that is considered abusive in one culture may be considered acceptable in another (e.g., corporal punishment).

- Parental behaviour that is appropriate at one stage in a child’s development may be inappropriate at another stage of development (e.g., the level of supervision needed for toddlers versus adolescents).

- The potential perpetrators of maltreatment need to be defined, so as not to inadvertently exclude particular behaviours and contexts. However, disagreement exists over whom should be included as potential perpetrators in the definitions of certain maltreatment subtypes.

- Researchers often use categorical definitions of child maltreatment (i.e., a child is either maltreated or not maltreated). However, this approach fails to acknowledge that abusive and neglectful behaviours can differ markedly in terms of severity, the frequency and duration of occurrence, and the likelihood that they will cause physical or emotional harm.

- Child maltreatment can be defined either using abusive or neglectful adult behaviours (e.g., the definition of child physical abuse would comprise parental behaviours such as hitting or shaking), or by the harm caused to the child as a result of such behaviours (e.g., child physical abuse would be indicated if the child displayed physical symptoms such as bruising or swelling).

- Although perpetrator intent to maltreat a child is often a useful indicator of child maltreatment, there are a number of instances where abuse or neglect can occur even though the perpetrator did not intend to commit it (e.g., neglectful parents may have had no intention of neglecting their children) (Bromfield, 2005; Feerick et al., 2006; US National Research Council, 1993).

Let’s take a closer look at each if these major types of child maltreatment.

PHYSICAL ABUSE

Generally, child physical abuse refers to the non-accidental use of physical force against a child that results in harm to the child. However, a parent does not have to intend to physically harm their child to have physically abused them (e.g., physical punishment that results in bruising would generally be considered physical abuse). Depending on the age and the nature of the behaviour, physical force that is likely to cause physical harm to the child may also be considered abusive (e.g., a situation in which a baby is shaken but not injured would still be considered physically abusive). Physically abusive behaviours include shoving, hitting, slapping, shaking, throwing, punching, kicking biting, burning, strangling and poisoning. The fabrication or induction of an illness by a parent or carer (previously known as Munchausen syndrome by proxy) is also considered physically abusive behaviour (Bromfield, 2005; World Health Organization, 2006).

EMOTIONAL MALTREATMENT

Emotional maltreatment is also sometimes called ’emotional abuse,’ ‘psychological maltreatment’ or ‘psychological abuse’. Emotional maltreatment refers to a parent or caregiver’s inappropriate verbal or symbolic acts toward a child and/or a pattern of failure over time to provide a child with adequate non-physical nurture and emotional availability. Such acts of commission or omission have a high probability of damaging a child’s self-esteem or social competence (Bromfield, 2005; Garbarino, Guttman, & Seeley, 1986; World Health Organization, 2006). Emotional maltreatment can include when a caregiver or adult rejects or refuses to acknowledge the child’s needs. Some children are isolated from normative social experiences, preventing them from forming friendships (Gabarino et al., 1986). Caregivers can frighten children with verbal abuse, creating a climate of fear at home. Depriving children of opportunities for learning and intellectual development, and encouraging them to engage in antisocial behaviour constitute emotional maltreatment (Gabarino et. al., 1986). It is worth noting that some researchers classify emotionally neglectful behaviours (e.g., rejecting, ignoring) as a form of neglect. This does not pose a problem, as long as researchers explicitly indicate under which maltreatment subtype they record such behaviours. There is certainly common conceptual ground between some types of emotional maltreatment and some types of neglect, which serves to illustrate that the different maltreatment subtypes are not always neatly demarcated.

NEGLECT

Neglect refers to the failure by a parent or caregiver to provide a child (where they are in a position to do so) with the conditions that are culturally accepted in a society as being essential for their physical and emotional development and wellbeing (Broadbent & Bentley, 1997; Bromfield, 2005; Scott, 2014; World Health Organization, 2006). Common forms of child neglect include a consistent lack of appropriate adult supervision and the failure to provide basic physical necessities such as clothing and food. The failure of caregivers to meet the medical needs of children, or by deliberately withholding treatment, can have fatal consequences. Similarly, caregivers can fail to support a child engaging in education or regularly attend school (Scott, 2014). Finally, children left alone for more than a reasonable period and not providing them with appropriate alternate care can have adverse consequences for the child’s development (Scott, 2014).

SEXUAL ABUSE

Defining sexual abuse is a complicated task. Although some behaviours are considered sexually abusive by almost everyone (e.g., the rape of a 10-year-old child by a parent), other behaviours are much more equivocal (e.g., consensual sex between a 19-year-old and a 15- year-old) and judging whether or not they constitute abuse requires a sensitive understanding of a number of definitional issues specific to child sexual abuse. In places such as Australia where there are multiple legal definitions of child sexual abuse, a more general definition may be useful (Quadara, Nagy, Higgins, & Siegel, 2015).

The World Health Organization (WHO, 1999) defines child sexual abuse as the involvement of a child in sexual activity that he or she does not fully comprehend, is unable to give informed consent to … or that violate the laws or social taboos of society. Child sexual abuse is evidenced by this activity between a child and an adult or another child who by age or development is in a relationship of responsibility, trust or power, the activity being intended to gratify or satisfy the needs of the other person (WHO, 1999). Sexually abusive behaviours can include the fondling of genitals, masturbation, oral sex, vaginal or anal penetration by a penis, finger or any other object, fondling of breasts, voyeurism, exhibitionism and exposing the child to or involving the child in pornography (Bromfield, 2005; US National Research Council, 1993).

However, unlike the other maltreatment types, the definition of child sexual abuse varies depending on the relationship between the victim and the perpetrator. For example, any sexual behaviour between a child and a member of their family (e.g., parent, uncle) would always be considered abusive, while sexual behaviour between two adolescents may or may not be considered abusive, depending on whether the behaviour was consensual, whether any coercion was present, or whether the relationship between the two young people was equal (Ryan, 1997). Thus, there are different definitions for each class of perpetrator: adults with no familial relationship to the child, adult family members of the child, adults in a position of power or authority over the child (e.g., teacher, doctor), adolescent or child perpetrators, and adolescent or child family members.

According to Smallbone et al. (2013) there are four dimensions of child sexual abuse: relationships, contexts or settings, victim vulnerabilities and grooming strategies. These are not mutually exclusive, but are used to highlight the idea that some forms of child sexual abuse are made possible and are shaped by the relationships between victims and perpetrators, while other forms of child sexual abuse are significantly shaped by the settings and contexts in which victims and perpetrators come together. This is highlighted by the notion that sexual abuse is only possible at the convergence or interaction of two factors: the person (both victim and offender) and the situation (context or setting) (Smallbone et al., 2013). Furthermore, adult perpetrators typically target children who appear vulnerable (due to family dysfunction, social isolation, disability, etc.), and employ a range of grooming strategies to develop trust and intimacy with the child, which enables sexualisation of the relationship to occur (Salter, 1995). Any sexual behaviour between a child under the age of consent and an adult is abusive. The age of consent is 16 years in most Australian states. In Australia, consensual sexual activity between a 20-year-old and a 15-year-old is considered abusive, while in most jurisdictions the same activity between a 20-year-old and a 17-year-old is not considered abusive.

Communication technologies facilitate a range of sexually abusive behaviours and allow perpetrators to have anonymous contact with a large number of children. Forms of perpetration include grooming children in a virtual environment such as through instant messaging, accessing child exploitation material, and producing and distributing exploitation material even where there is no sexual interest in children. Online sexual abuse behaviours are often active with perpetrators seeking out minors online, and perpetrators may move from making connections with children online to making contact offline (Quadara et al., 2015). Any sexual behaviour between a child and an adult family member is abusive. The concepts of consent, equality and coercion are inapplicable in instances of intra-familial abuse.

Sexual abuse occurs when there is any sexual behaviour between a child and an adult in a position of power or authority over them (e.g., a teacher). The age of consent laws is inapplicable in such instances due to the strong imbalance of power that exists between children and authority figures, as well as the breaching of both personal and public trust that occurs when professional boundaries are violated.

Sexual abuse occurs when there is sexual activity between a child and an adolescent or child family member that is non-consensual or coercive, or where there is an inequality of power or development between the two young people. Although consensual and non-coercive sexual behaviour between two developmentally similar family members is not considered child sexual abuse, it is considered incest, and is strongly proscribed both socially and legally in Australia.

EXPOSURE TO FAMILY VIOLENCE

Exposure to family violence has been broadly defined as “a child being present (hearing or seeing) while a parent or sibling is subjected to physical abuse, sexual abuse or psychological maltreatment, or is visually exposed to the damage caused to persons or property by a family member’s violent behaviour” (Higgins, 1998, p. 104). Narrower definitions refer only to children being exposed to domestic violence between intimate partners.

Some researchers classify the witnessing of family violence as a special form of emotional maltreatment. However, a growing number of professionals regard the exposure to family violence as a unique and independent subtype of abuse (Bromfield, 2005; Higgins, 2004; James, 1994). Regardless of the classification used, research has shown that children who are exposed to domestic violence tend to experience significant disruptions in their psychosocial wellbeing, often exhibiting a similar pattern of symptoms to other abused or neglected children (Kitzmann, Gaylord, Holt, & Kenny, 2003; Tomison, 2000).

OTHER FORMS OF CHILD MALTREATMENT

As well as the five main subtypes of child maltreatment, researchers have identified others, including:

- fetal abuse (i.e., behaviours by pregnant mothers that could endanger a fetus, such as the excessive use of tobacco, alcohol or illicit drugs)

- bullying, or peer abuse

- sibling abuse

- exposure to community violence

- institutional abuse (i.e., abuse that occurs in institutions such as foster homes, group homes, voluntary organisations such as the Scouts, and child care centres)

- organised exploitation (e.g., child sex rings, child pornography, child prostitution); and

- state-sanctioned abuse (e.g., female genital mutilation in parts of Africa, and the ‘Stolen Generations’ in Australia) (Corby, 2006; Miller-Perrin & Perrin, 2007).

RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN DIFFERENT FORMS OF ABUSE

Although it is useful to distinguish between the different subtypes of child maltreatment in order to understand and identify them more thoroughly, it can also be slightly misleading. It is misleading if it creates the impression that there are always strong lines of demarcation between the different abuse subtypes, or that abuse subtypes usually occur in isolation. There is a growing body of evidence to suggest that maltreatment subtypes seldom occur in isolation; the majority of individuals with a history of maltreatment report exposure to two or more subtypes (Arata, Langhinrichsen-Rohling, Bowers, & O’Farrill-Swails, 2005; Higgins & McCabe, 2000; Ney, Fung, & Wickett, 1994). Additionally, some acts of violence against children involve multiple maltreatment subtypes. For example, an adult who sexually abuses a child may simultaneously hit them (i.e., physical abuse) and isolate or terrorise them (e.g., emotional abuse). Similarly, when parents subject their children to sexual or physical abuse, the emotional harm and betrayal of trust implicit in these acts need to also be thought of as a form of emotional maltreatment.

PREVALENCE OF CHILD MALTREATMENT

Prevalence refers to the proportion of a population that has experienced a phenomenon, for example the percentage of Australians aged 18 years and over in 2015 who were ever abused or neglected as a child. Incidence refers to the number of new cases occurring over a specified period of time (normally a year), for example the number of Australian children aged 0–17 years who were abused or neglected during 2015 (Mathews et al., 2016).

Australia is one of the only developed countries where there has been no methodologically rigorous, nationwide study of the prevalence or incidence of child abuse and neglect (Mathews et al., 2016) There are, however, a number of recent studies that have either measured one or two maltreatment types in detail or have superficially measured all individual maltreatment types as part of a larger study.

Physical Abuse: Six contemporary Australian studies and one systematic review (encompassing some of the same studies) have measured the prevalence of child physical abuse within relatively large community samples. Prevalence estimates ranged from 5%-18%, with the majority of studies finding rates between 5% and 10%.

Neglect: Three contemporary Australian studies have measured child neglect in community samples. Prevalence estimates of neglect ranged from 1.6% to 4%.

Emotional Maltreatment: Three Australian studies and one Australian systematic review have estimated the prevalence of emotional maltreatment. Although the studies were all conducted with relatively large community samples, their prevalence estimates were quite different, ranging from 6% (Rosenman & Rodgers, 2004) to 17% (Price-Robertson et al., 2010). This large range is likely due to differences in the wording of questions. For example, Rosenman and Rodgers (2004) defined emotional maltreatment using stronger terms (e.g., ‘mental cruelty’) than Price-Robertson and colleagues (e.g., “humiliated”). The best available evidence suggests that the prevalence rate for emotional maltreatment in Australia is between 9% and 14% (Chu et al., 2013; Moore et al., 2015).

Exposure to family violence: Four community-based studies have estimated the extent to which Australian children are exposed to family violence. Prevalence estimates were from self- reported exposure, and ranged from 4% to 23% of children.

Sexual maltreatment: Studies that comprehensively measured the prevalence of child sexual maltreatment found that males had prevalence rates of 1.4-7.5% for penetrative abuse and 5.2- 12% for non-penetrative abuse, while females had prevalence rates of 4.0-12.0% for penetrative abuse and 14-26.8% for non-penetrative abuse (Price-Robertson et al., 2010

ReMOVED Statistics [41 secs]

Watch this short video to understand some key statistics about children who have been maltreated. Please note that the clip contains themes and images that may be distressing to some. Please feel free to stop watching the video if you are distressed.

A transcript and Closed Captions are also available within the video.

References

Arata, C. M., Langhinrichsen-Rohling, J., Bowers, D., & O’Farrill-Swails, L. (2005). Single versus multi-type maltreatment: An examination of the long-term effects of child abuse. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 11(4), 29-52.

Bailey, C., Powell, M., & Brubacher, S. P. (2017). The attrition of indigenous and non-indigenous child sexual abuse cases in two Australian jurisdictions. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 23(2), 178.

Broadbent, A., & Bentley, R. (1997). Child abuse and neglect Australia 1995-96 (Child Welfare Series No. 17). Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Retrieved from www.aihw.gov.au/publication-detail/?id=6442466882

Bromfield, L. M. (2005). Chronic child maltreatment in an Australian Statutory child protection sample (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Deakin University, Geelong.

Christoffel, K. K., Scheidt, P. C., Agran, P. F., Kraus, J. F., McLoughlin, E., & Paulson, J. A. (1992). Standard definitions for childhood injury research: Excerpts of a conference report. Pediatrics, 89(6), 1027-1034.

Chu, D. A., Williams, L. M., Harris, A. W., Bryant, R. A., & Gatt, J. M. (2013). Early life trauma predicts self-reported levels of depressive and anxiety symptoms in nonclinical community adults: relative contributions of early life stressor types and adult trauma exposure. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 47(1), 23-32.

Corby, B. (2006). Child abuse: Towards a knowledge base (3rd ed.). Berkshire, England: Open University Press.

Feerick, M. M., & Snow, K. L. (2006). An examination of research in child abuse and neglect: Past practices and future directions. In M. M. Feerick, J. F. Knutson, P. K. Trickett, & S. M. Flanzer (Eds.), Child abuse and neglect: Definitions, classification, and a framework for research. Baltimore, Maryland: Paul H. Brooks Publishing Company.

Garbarino, J., Guttman, E., & Seeley, J. W. (1986). The psychologically battered child: Strategies for identification, assessment, and intervention. San Francisco, California: Jossey-Bass Inc.

Higgins, D. J. (2004). Differentiating between child maltreatment experiences. Family Matters, 69, 50-55.

Higgins, D. J., & McCabe, M. P. (1998). Parent perceptions of maltreatment and adjustment in children. Journal of Family Studies, 4(1), 53-76.

Higgins, D. J., & McCabe, M. P. (2000b). Relationships between different types of maltreatment during childhood and adjustment in adulthood. Child Maltreatment, 5(3), 261-272.

James, M. (1994). Domestic violence as a form of child abuse: Identification and prevention (NCPC Issues No. 2). Melbourne: National Child Protection Clearinghouse. Retrieved from www.aifs.gov.au/nch/pubs/issues/issues2/issues2.html

Kitzmann, K. M., Gaylord, N. K., Holt, A. R., & Kenny, E. D. (2003). Child witnesses to domestic violence: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71(2), 339- 352.

Mathews, B., Walsh, K., Dunne, M., Katz, I., Arney, F., Higgins, D., Octoman, O., Parkinson, S., & Bates, S. (2016). Scoping study for research into the prevalence of child abuse in Australia: Report into the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse (SPRC Report 13/16). Sydney: Social Policy Research Centre, UNSW in partnership with Australian Institute of Family Studies, Queensland University of Technology and the Australian Centre for Child Protection.

Miller-Perrin, C., & Perrin, R. (2007). Child maltreatment: An introduction. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications.

Moore, S. E., Scott, J. G., Ferrari, A. J., Mills, R., Dunne, M. P., Erskine, H. E., … & Norman, R. E. (2015). Burden attributable to child maltreatment in Australia. Child Abuse & Neglect, 48, 208-220

Ney, P. G., Fung, T., & Wickett, A. R. (1994). The worst combinations of child abuse and neglect. Child Abuse & Neglect, 18(9), 705-714.

Price-Robertson, R., Smart, D., & Bromfield, L. (2010). Family is for life: Connections between childhood family experiences and wellbeing in early adulthood. Family Matters, 85, 7-17.

Quadara, A., Nagy, V., Higgins, D., & Siegel, N. (2015). Conceptualising the prevention of child sexual abuse: Final report (Research Report No. 33). Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies. Retrieved from <aifs.gov.au/publications/conceptualising-prevention-child-

Rosenman, S., & Rodgers, B. (2004). Childhood adversity in an Australian population. Social Psychiatry & Psychiatric Epidemiology, 39, 695-702.

Ryan, G. (1997). Sexually abusive youth: Defining the population. In G. Ryan & S. Lane (Eds.), Juvenile sexual offending: Causes, consequences, and correction (pp. 3-9). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Salter, A. C. (1995). Transforming trauma: A guide to understanding and treating adult survivors of child sexual abuse. Sage Publications.

Scott, D. (2014). Understanding child neglect (CFCA Paper No. 20). Melbourne: Child Family Community Australia, Australian Institute of Family Studies. Retrieved from <aifs.gov.au/cfca/publications/understanding-child-neglect>

Schore, A. N. (2015). Affect regulation and the origin of the self: The neurobiology of emotional development. Routledge.

Smallbone, S., Marshall, W. L., & Wortley, R. (2013). Preventing child sexual abuse: Evidence, policy and practice. Routledge.

Tomison, A. M. (2000). Exploring family violence: Links between child maltreatment and domestic violence (Issues Paper No. 13). Melbourne: National Child Protection Clearinghouse. Retrieved from <aifs.gov.au/cfca/publications/exploring-family-violence-links-between-child-maltreatment>

US National Research Council. (1993). Understanding child abuse and neglect. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

World Health Organization. (1999). Report of the consultation on child abuse prevention. Geneva: WHO. Retrieved from www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/65900

World Health Organization. (2006). Preventing child maltreatment: A guide to taking action and generating evidence. Geneva: WHO. Retrieved from www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/publications/violence/child_maltreatment/en/