Conflict Theory and Deviance

Learning Outcomes

- Explain how conflict theorists understand deviance

Conflict Theory

Conflict theory looks to social and economic factors as the causes of crime and deviance. Unlike functionalists, conflict theorists don’t see these factors as positive functions of society. They see them as evidence of inequality in the system. They also challenge social disorganization theory and control theory and argue that both ignore racial and socioeconomic issues and oversimplify social trends (Akers 1991). Conflict theorists also look for answers to the correlation of gender and race with wealth and crime.

Karl Marx: An Unequal System

Conflict theory was greatly influenced by the work of 19th-century German philosopher, economist, and social scientist Karl Marx. Marx believed that the general population was divided into two groups. He labeled the wealthy, who controlled the means of production and business, the bourgeoisie. He labeled the workers who depended on the bourgeoisie for employment and survival the proletariat. Marx believed that the bourgeoisie centralized their power and influence through government, laws, and other authority agencies in order to maintain and expand their positions of power in society. Thus, Marx viewed the laws as instruments of oppression for the proletariat that are written and enforced to maintain the economic status quo and to protect the interests of the ruling class. Though Marx spoke little of deviance, he wrote a great deal about laws and developed a legal theory that created the foundation for conflict theorists.

C. Wright Mills: The Power Elite

In his book The Power Elite (1956), sociologist C. Wright Mills described the existence of what he dubbed the power elite, a small group of wealthy and influential people at the top of society who disproportionately control power and resources. Wealthy executives, politicians, celebrities, and military leaders often have access to national and international power, and in some cases, their decisions affect everyone in society. Because of this, the rules of society are stacked in favor of a privileged few who then manipulate them to maintain their positions. It is these people who decide what is criminal and what is not, and the effects are often felt most by those who have little power. Mills’ theories explain why celebrities such as Chris Brown and Paris Hilton, or once-powerful politicians such as Eliot Spitzer and Tom DeLay, can commit crimes and suffer little or no legal retribution.

Try It

Crime, Social Class, and Race

While crime is often associated with the underprivileged, crimes committed by the wealthy and powerful remain an under-punished and costly problem within society. The American Sociological Association’s 1939 President Edwin Sutherland coined the term “white-collar crime” in his address “White Collar Criminality,” which was one of the few such addresses to make front-page news.[1] He defined the term as “crime committed by a person of respectability and high social status in the course of his occupation.” Typically, these are “nonviolent crimes committed in commercial situations for financial gain” and according to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), white-collar crime is estimated to cost the United States more than $300 billion annually. [2] When former advisor and financier Bernie Madoff was arrested in 2008, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission reported that the estimated losses of his financial Ponzi scheme fraud were close to $50 billion (SEC 2009). In contrast, property crimes, which include burglary, larceny-theft, motor vehicle theft, and arson, in 2015 resulted in losses estimated at $14.3 billion (FBI 2015).

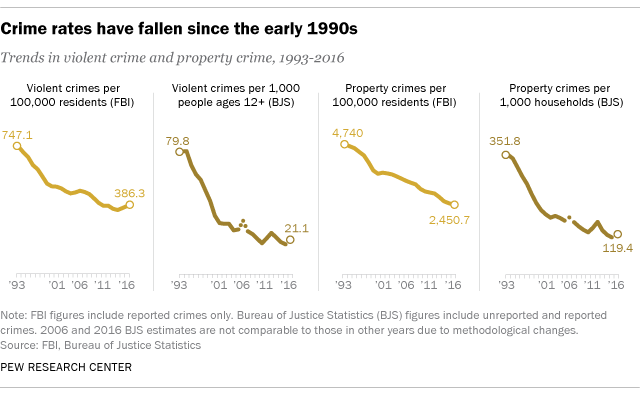

Conflict theorists also quickly point out that “crime in the suites” is often committed by white men, whereas “crime in the streets” disproportionately affects communities of color as both perpetrators and victims of property crimes. Property crimes have fallen dramatically over the past twenty years (see chart below); it is also important to keep in mind that only 36 percent of property crimes are reported to police[3]

Crack, Cocaine, and Opioids

In the 1980s, there was a “crack epidemic” that swept the country’s poorest urban communities. Its pricier counterpart, cocaine, was often the drug of choice for wealthy whites. Most studies show rates of drug use among whites and Blacks were similar. From a pharmaceutical standpoint, crack and cocaine are nearly the same in terms of effect.

In 1986, federal law mandated that being caught in possession of 50 grams of crack was punishable by a ten-year prison sentence. An equivalent prison sentence for cocaine possession, however, required possession of 5,000 grams. In other words, the sentencing disparity was 1 to 100 (New York Times Editorial Staff 2011). This inequality in the severity of punishment for crack versus cocaine paralleled the class and race of the respective users.

A conflict theorist would note that those in society who hold the power make the laws concerning crime that benefit their own interests, while the powerless classes who lack the resources to make such decisions suffer the consequences. Thus, since powder cocaine use was associated with wealthy whites, the laws were enacted to be lenient on powder cocaine but extremely punitive toward crack-cocaine. The crack-cocaine punishment disparity remained until 2010, when President Obama signed the Fair Sentencing Act, which decreased the disparity to 1 to 18 (The Sentencing Project 2010).

Today, we are in the midst of an “opioid epidemic.” Unlike the 1980s crack epidemic, the opioid epidemic is considered a public health crisis and has widespread support for prevention and treatment programs. Since disproportionate numbers of drug overdose deaths have been among white Americans, conflict theorists would suggest that those in power are more likely to advocate policy changes to help these drug addicts rather than punish them. Why are whites more likely to overdose? The answer, ironically, might be racism; studies show that doctors are more reluctant to prescribe painkillers to minorities because they mistakenly believe minority patients feel less pain and/or are more likely to misuse or sell the prescribed drugs[4]

Try It

Feminist Theory and Deviance

Women who are regarded as criminally deviant are often seen as being doubly deviant. They have broken the laws but they have also violated gender norms governing appropriate female behavior, whereas men’s criminal behavior is seen as consistent with their ostensibly aggressive, self-assertive character. This double standard also explains the tendency to medicalize women’s deviance, to see it as the product of physiological or psychiatric pathology. For example, in the late 19th century, kleptomania was a diagnosis used in legal defenses that linked an extreme desire for department store commodities with various forms of female physiological or psychiatric illness. The fact that “good” middle- and upper-class women, who were at that time coincidentally beginning to experience the benefits of independence from men, would turn to stealing in department stores to obtain the new feminine consumer items on display there, could not be explained without resorting to diagnosing the activity as an illness of the “weaker” sex (Kramar 2011).

Feminist analysis focuses on the way gender inequality influences the opportunities to commit crime and the definition, detection, and prosecution of crime. In part the gender difference revolves around patriarchal attitudes toward women and the disregard for matters considered to be of a private or domestic nature.

For example, until 1969, abortion was illegal in Canada, meaning that hundreds of women died or were injured each year when they received illegal abortions (McLaren and McLaren 1997). It was not until the Canadian Supreme Court ruling in 1988 that struck down the law that it was acknowledged that women are capable of making their own choice, in consultation with a doctor, about the procedure. The U.S. Supreme Court in Roe v. Wade (1973) decided in a 7-2 decision that states cannot unduly restrict abortions. Since then, a plethora of restrictions including waiting periods, restrictions on public funding for abortions, mandated counseling, parental involvement for minors, and others have made it exceedingly difficult. The State of Mississippi, for example, has one abortion clinic in the state, whereas California has 152 clinics as of 2014. Read about other differences between the most restrictive state, Mississippi, and the least restrictive state, California.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), an African-American woman is almost five times as likely to have an abortion than a white woman, and a Latina more than twice as likely.[5]

Abortion has been declining with approximately 1.1 million abortions performed in 2011, at a rate of 16.9 abortions for every 1,000 women of childbearing age, down from a peak of 29.3 per 1,000 in 1981 (Dutton 2014). Low-income women in all racial groups are more likely to experience unintended pregnancies, largely due to a lack of health insurance and access to contraception. The most effective and long-term contraception, an intrauterine device or IUD, costs between $500-1000 and office visit fees are in addition to the cost of the IUD itself; community health centers and Medicaid typically do not cover 100% of the costs, but often IUDs are covered by private insurance.

Regulating women’s bodies is nothing new, particularly when it comes to minority women in the U.S. White slaveowners raped Black female slaves with impunity and then increased their “property” with the offspring. Nearly one-third of women of child-bearing age in Puerto Rico were sterilized between 1930 and 1970, as funded by the U.S. Department of Health, Welfare, and Funding to mitigate high levels of unemployment and poverty. Although this was “voluntary,” women were often pressured to undergo sterilization after giving birth[6]

In addition to examining the ways in which the state regulates women’s bodies, feminist theorists also look at violent crimes against women that are sexual in nature. In the #metoo era, women from many different groups (i.e. actors, gymnasts, students) have come forward to say that they were sexually harassed and/or sexually assaulted by a boss or supervisor, a team doctor, a university gynecologist, or other co-workers. The broadcast media and social media have been rife with stories of #metoo, which feminists are examining from a macrosociological approach (power and structures of power) and a microsociological approach (hashtag movement, personal identification with others who have similar experiences).

Sexual Assault in Canada: A Case Study

Until the 1970s, two major types of criminal deviance were largely ignored or were difficult to prosecute as crimes: sexual assault and spousal assault. Through the 1970s, women worked to change the criminal justice system and establish rape crisis centers and battered women’s shelters, bringing attention to domestic violence. In 1983 the Criminal Code was amended to replace the crimes of rape and indecent assault with a three-tier structure of sexual assault (ranging from unwanted sexual touching that violates the integrity of the victim to sexual assault with a weapon or threats or causing bodily harm to aggravated sexual assault that results in wounding, maiming, disfiguring, or endangering the life of the victim) (Kong et al. 2003). Johnson (1996) reported that in the mid-1990s, when violence against women began to be surveyed systematically in Canada, 51 percent of Canadian women had been subject to at least one sexual or physical assault since the age of 16.

The goal of the amendments was to emphasize that sexual assault is an act of violence, not a sexual act. Previously, rape had been defined as an act that involved penetration and was perpetrated against a woman who was not the wife of the accused. This had excluded spousal sexual assault as a crime and had also exposed women to secondary victimization by the criminal justice system when they tried to bring charges. Secondary victimization occurs when the women’s own sexual history and her willingness to consent are questioned in the process of laying charges and reaching a conviction, which as feminists pointed out, increased victims’ reluctance to press charges.

In particular feminists challenged the twin myths of rape that were often the subtext of criminal justice proceedings presided over largely by men (Kramar 2011). The first myth is that women are untrustworthy and tend to lie about assault out of malice toward men, as a way of getting back at them for personal grievances. The second myth, is that women will say “no” to sexual relations when they really mean “yes.” Typical of these types of issues was the judge’s comment in a Manitoba Court of Appeals case in which a man pleaded guilty to sexually assaulting his twelve- or thirteen-year-old babysitter:

The girl, of course, could not consent in the legal sense, but nonetheless was a willing participant. She was apparently more sophisticated than many her age and was performing many household tasks including babysitting the accused’s children. The accused and his wife were somewhat estranged (cited in Kramar 2011).

Because the girl was willing to perform household chores in place of the man’s estranged wife, the judge assumed she was also willing to engage in sexual relations. In order to address this type of issue, feminists successfully pressed the Supreme Court to deliver rulings that restricted a defense attorney’s access to a victim’s medical and counselling records, and rules of evidence were changed to prevent a woman’s past sexual history from being used against her. Consent to sexual intercourse was redefined as what a woman actually says or does, not what the man believes to be signalling consent. Feminists also argued that spousal assault was a key component of patriarchal power. Typically it was hidden in the household and largely regarded as a private, domestic matter in which police were reluctant to get involved.

Interestingly, women and men report similar rates of spousal violence—in 2009, 6 percent had experienced spousal violence in the previous five years—but women are more likely to experience more severe forms of violence including multiple victimizations and violence leading to physical injury (Sinha 2013). In order to empower women, feminists pressed lawmakers to develop zero-tolerance policies that would support aggressive policing and prosecution of offenders. These policies oblige police to pursue charges in cases of domestic violence when a complaint is made, whether or not the victim wishes to press charges (Kramar 2011).

In 2009, 84 percent of violent spousal incidents reported by women to police resulted in charges being pursued. However, according to victimization surveys only 30 percent of actual incidents were reported to police. The majority of women who did not report incidents to the police stated that they either dealt with them in another way, felt they were a private matter, or did not think the incidents were important enough to report. A significant proportion, however, did not want anyone to find out (44 percent), did not want their spouse to be arrested (40 percent), or were too afraid of their spouse (19 percent) (Sinha 2013).

Watch It

Watch the selected clip from this video to examine how conflict theorists think about deviance.

Think It Over

- Pick a famous politician, business leader, or celebrity who has been arrested recently. What crime did he or she allegedly commit? Who was the victim? Explain his or her actions from the point of view of one of the major sociological paradigms. What factors best explain how this person might be punished if convicted of the crime?

- In what ways do race and class intersect when theorizing deviance from a conflict perspective?

Glossary

- conflict theory:

- a theory that examines social and economic factors as the causes of criminal deviance

- doubly deviant:

- a term used to refer to females who have broken the law and gender norms about appropriate female behavior

- power elite:

- a small group of wealthy and influential people at the top of society who hold the power and resources

- secondary victimization:

- occurs when the women’s own sexual history and her willingness to consent are questioned in the process of laying charges and reaching a conviction

- twin myths of rape:

- the first myth is that women are untrustworthy and tend to lie about assault out of malice toward men, as a way of getting back at them for personal grievances and the second myth is that women will say “no” to sexual relations when they really mean “yes”

<a style="margin-left: 16px;" href="https://docs.google.com/document/d/1vy-T6DtTF-BbMfpVEI7VP_R7w2A4anzYZLXR8Pk4Fu4" target="_blank"

- Edwin H. Sutherland, ASA Presidents, ASA. http://www.asanet.org/edwin-h-sutherland ↵

- "White-collar crime." Legal Information Institute, Cornell Law School. https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/white-collar_crime. ↵

- Gramlich, J. "Five facts about crime," Pew Research Center.(2018) https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/10/17/facts-about-crime-in-the-u-s/ ↵

- Lopez, G. (2016). Why are Black Americans less affected," Vox. https://www.vox.com/2016/1/25/10826560/opioid-epidemic-race-black ↵

- Dutton, Z. (2014). Abortion's racial gap. https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2014/09/abortions-racial-gap/380251/ ↵

- Andrews, K. (2017) The dark history of latina sterilization. https://www.panoramas.pitt.edu/health-and-society/dark-history-forced-sterilization-latina-women. ↵