Divorce and Remarriage

Learning Outcomes

- Understand the social and interpersonal impacts of divorce

Divorce

Divorce, while fairly common and accepted in modern U.S. society, was once a word that would only be whispered and which was accompanied by gestures of disapproval. In 1960, divorce was generally uncommon, affecting only 9.1 out of every 1,000 married persons. That number more than doubled (to 20.3) by 1975 and peaked in 1980 at 22.6 (Popenoe 2007). Over the last quarter century, divorce rates have dropped steadily and are now similar to those in 1970. The dramatic increase in divorce rates after the 1960s has been associated with the liberalization of divorce laws, and to the shift in societal makeup due to women increasingly entering the workforce (Michael 1978). The decrease in divorce rates can be attributed to two probable factors: an increase in the age at which people get married, and an increased level of education among those who marry—both of which have been found to promote greater marital stability.

Divorce does not occur equally among all people in the United States; some segments of the U.S. population are more likely to divorce than others. According the American Community Survey (ACS), men and women in the Northeast have the lowest rates of divorce at 7.2 and 7.5 per 1,000 people. The South has the highest rate of divorce at 10.2 for men and 11.1 for women. Divorce rates are likely higher in the South because marriage rates are higher and marriage occurs at younger-than-average ages in this region. In the Northeast, the marriage rate is lower and first marriages tend to be delayed; therefore, the divorce rate is lower (U.S. Census Bureau 2011). More specifically, our nation’s capital, Washington D.C. has the highest rates of divorce with a rate of 29.9 per 1,000 in 2015 and Hawaii and the lowest with 11.1 percent per 1,000 [1]

The rate of divorce also varies by race. In a 2009 ACS study, American Indian and Alaskan Natives reported the highest percentages of currently divorced individuals (12.6 percent) followed by Blacks (11.5 percent), whites (10.8 percent), Pacific Islanders (8 percent), Latinos (7.8 percent) and Asians (4.9 percent) (ACS 2011). In general those who marry at a later age, and who have a college education have lower rates of divorce.

Try It

So what causes divorce? While more young people are choosing to postpone or opt out of marriage, those who enter into the union do so with the expectation that it will last. A great many marital problems can be related to stress, especially financial stress. According to researchers participating in the University of Virginia’s National Marriage Project, couples who enter marriage without a strong asset base (like a home, savings, and a retirement plan) are 70 percent more likely to be divorced after three years than are couples with at least $10,000 in assets. This is connected to factors such as age and education level that correlate with low incomes.

The addition of children to a marriage creates added financial and emotional stress. Research has established that marriages enter their most stressful phase upon the birth of the first child (Popenoe and Whitehead 2007). This is particularly true for couples who have multiples (twins, triplets, and so on). Married couples with twins or triplets are 17 percent more likely to divorce than those with children from single births (McKay 2010). Another contributor to the likelihood of divorce is a general decline in marital satisfaction over time. As people get older, they may find that their values and life goals no longer match up with those of their spouse (Popenoe and Whitehead 2004).

Remarriage

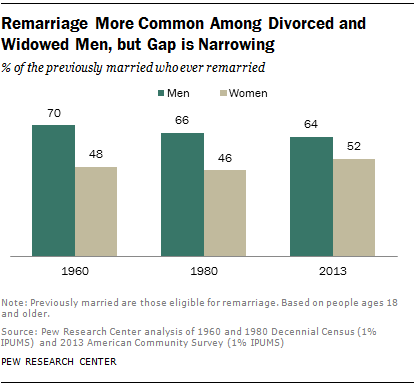

In 2013, 23 percent of married people had been married before,[2] compared with just 13 percent in 1960. In 2013, 4 out of 10 new marriages included at least one partner who had been previously married and half of these (2 out of 10) include two spouses who were remarrying (Geiger and Livingston 2019). Previously married men are more likely to get married again, with 64 percent getting married twice compared to 52 percent of women, but this could be an indication of desire—54 percent of women say they do not want to remarry as opposed to 30 percent of men (Geiger and Livingston 2019).

People in a second marriage account for approximately 19.3 percent of all married persons, and those who have been married three or more times account for 5.2 percent (U.S. Census Bureau 2011). The vast majority (91 percent) of remarriages occur after divorce; only 9 percent occur after death of a spouse (Kreider 2006). Most men and women remarry within five years of a divorce, with the median length for men (three years) being lower than for women (4.4 years). This length of time has been fairly consistent since the 1950s. The majority of those who remarry are between the ages of twenty-five and forty-four (Kreider 2006). The general pattern of remarriage also shows that whites are more likely to remarry than Hispanics, Blacks, or Asians.

Marriage the second time around (or third or fourth) can be a very different process than the first. Remarriage lacks many of the classic courtship rituals of a first marriage. In a second marriage, individuals are less likely to deal with issues like parental approval, premarital sex, or desired family size (Elliot 2010). In a survey of households formed by remarriage, a mere 8 percent included only biological children of the remarried couple. Of the 49 percent of homes that include children, 24 percent included only the woman’s biological children, 3 percent included only the man’s biological children, and 9 percent included a combination of both spouse’s children (U.S. Census Bureau 2006).

Children of Divorce and Remarriage

Divorce and remarriage can be stressful on partners and children alike. Divorce is often justified by the notion that children are better off in a divorced family than in a family with parents who do not get along, but many other variables are important, such as the parental involvement of the non-custodial parent and the socioeconomic status of the custodial parent.

Children’s ability to deal with a divorce may depend on their age. Research has found that divorce may be most difficult for school-aged children, as they are old enough to understand the separation but not old enough to understand the reasoning behind it. Older teenagers are more likely to recognize the conflict that led to the divorce but may still feel fear, loneliness, guilt, and pressure to choose sides. Infants and preschool-age children may suffer the heaviest impact from the loss of routine that the marriage offered (Temke 2006).

Proximity to parents also makes a difference in a child’s well-being after divorce. Boys who live or have joint arrangements with their fathers show less aggression than those who are raised by their mothers only. Similarly, girls who live or have joint custody arrangements with their mothers tend to be more responsible and mature than those who are raised by their fathers only. Nearly three-fourths of the children of parents who are divorced live in a household headed by their mother, leaving many boys without a father figure residing in the home (U.S. Census Bureau 2011b). Still, researchers suggest that a strong parent-child relationship can greatly improve a child’s adjustment to divorce (Temke 2006).

Watch It: Families and inequality

Sociologist Annette Lareau studied class differences in family life by closely following 88 families from various socioeconomic backgrounds. She found middle-class parents to be more involved in their children’s education, but not because lower-class parents were disinterested in their children’s learning. Both wanted the best for their children, but Lareau found that parents approached education and family life in different ways.

On the whole, middle-class parents were more likely to spend time investing in their children’s education while at home and through various extracurricular activities, whereas many of the lower-class parents viewed the schools as specialists and teachers as experts who had the primary responsibility for educating their children. Also due to time and monetary constraints, lower-class children had more unstructured time and autonomy, which also led to greater creativity. Middle-class parents were more likely to read and talk with their kids, be involved in their schoolwork, and supplement their school education.[3]

In her 2003 book, Unequal Childhoods, Lareau used the terms concerted cultivation and accomplishment of natural growth to describe the differences in parenting styles. Each parenting style is described below:

- Concerted Cultivation: The parenting style, favored by middle-class families, in which parents encourage negotiation and discussion and the questioning of authority, and enroll their children in extensive organized activities. This style helps children eventually find their way to middle-class careers, teaches them to question people in authority, develops a larger, more fluent vocabulary, and makes them comfortable in discussions with people of authority. However, it may also give children a sense of entitlement.

- Accomplishment of Natural Growth: The parenting style, favored by working-class and lower-class families, in which parents issue directives to their children rather than negotiations, encourage the following and trusting of people in positions of authority, and do not structure their children’s daily activities, instead letting them play on their own. This method prepares the children for “working” or “poor-class” jobs, teaches them to respect and take the advice of people in authority, and allows the children to become independent at a younger age.

Try It

Learning Outcomes

- Explain how financial status impacts marital stability. What other factors are associated with a couple’s financial status?

- Why do you think divorced males are more likely to remarry and to do so more quickly than their female counterparts?

<a style="margin-left: 16px;" href="https://docs.google.com/document/d/1vy-T6DtTF-BbMfpVEI7VP_R7w2A4anzYZLXR8Pk4Fu4" target="_blank"

- "Divorce Rates in the U.S.: Geographic Variation," 2015. Bowling Green State University, https://www.bgsu.edu/ncfmr/resources/data/family-profiles/anderson-divorce-rate-us-geo-2015-fp-16-21.html. ↵

- Livingston, Gretchen. "Growing Number of Adults Have Remarried." Pew Research Center. Retrieved from https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2014/11/14/four-in-ten-couples-are-saying-i-do-again/. ↵

- McKenna, Laura (February 2012). Explaining Annette Lareau, or, Why Parenting Style Ensures Inequality. The Atlantic. Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2012/02/explaining-annette-lareau-or-why-parenting-style-ensures-inequality/253156/ ↵