Field Research

Learning Outcomes

- Explain the three types of field research: participant observation, ethnography, and case studies

Field Research

The work of sociology rarely happens in limited, confined spaces. Sociologists seldom study subjects in their own offices or laboratories. Rather, sociologists go out into the world. They meet subjects where they live, work, and play. Field research refers to gathering primary data from a natural environment without doing a lab experiment or a survey. It is a research method suited to an interpretive framework rather than to the scientific method. To conduct field research, the sociologist must be willing to step into new environments and observe, participate, or experience those worlds. In field work, the sociologists, rather than the subjects, are the ones out of their element.

The researcher interacts with or observes a person or people and gathers data along the way. The key point in field research is that it takes place in the subject’s natural environment, whether it’s a coffee shop or tribal village, a homeless shelter or the DMV, a hospital, airport, mall, or beach resort.

While field research often begins in a specific setting, the study’s purpose is to observe specific behaviors in that setting. Field work is optimal for observing how people behave. It is less useful, however, for understanding why they behave that way. You can’t really narrow down cause and effect when there are so many variables to be factored into a natural environment.

Many of the data gathered in field research are based not on cause and effect but on correlation. And while field research looks for correlation, its small sample size does not allow for establishing a causal relationship between two variables.

Parrotheads as Sociological Subjects

Some sociologists study small groups of people who share an identity in one aspect of their lives. Almost everyone belongs to a group of like-minded people who share an interest or hobby. Scientologists, Nordic folk dancers, or members of Mensa (an organization for people with exceptionally high IQs) express a specific part of their identity through their affiliation with a group. Those groups are often of great interest to sociologists.

Jimmy Buffett, an American musician who built a career from his top-10 song “Margaritaville,” has a following of devoted groupies called Parrotheads. Some of them have taken fandom to the extreme, making Parrothead culture a lifestyle. In 2005, Parrotheads and their subculture caught the attention of researchers John Mihelich and John Papineau. The two saw the way Jimmy Buffett fans collectively created an artificial reality. They wanted to know how fan groups shape culture.

What Mihelich and Papineau found was that Parrotheads, for the most part, do not seek to challenge or even change society, as many sub-groups do. In fact, most Parrotheads live successfully within society, holding upper-level jobs in the corporate world. What they seek is escape from the stress of daily life.

At Jimmy Buffett concerts, Parrotheads engage in a form of role play. They paint their faces and dress for the tropics in grass skirts, Hawaiian leis, and Parrot hats. These fans don’t generally play the part of Parrotheads outside of these concerts; you are not likely to see a lone Parrothead in a bank or library. In that sense, Parrothead culture is less about individualism and more about conformity in a group setting. Being a Parrothead means sharing a specific identity. Parrotheads feel connected to each other: it’s a group identity, not an individual one.

In their study, Mihelich and Papineau quote from a book by sociologist Richard Butsch, who writes, “un-self-conscious acts, if done by many people together, can produce change, even though the change may be unintended” (2000). Many Parrothead fan groups have performed good works in the name of Jimmy Buffett culture, donating to charities and volunteering their services.

However, the authors suggest that what really drives Parrothead culture is commercialism. Jimmy Buffett’s popularity was dying out in the 1980s until being reinvigorated after he signed a sponsorship deal with a beer company. These days, his concert tours alone generate nearly $30 million a year. Buffett made a lucrative career for himself by partnering with product companies and marketing Margaritaville in the form of T-shirts, restaurants, casinos, and an expansive line of products. Some fans accuse Buffett of selling out, while others admire his financial success. Buffett makes no secret of his commercial exploitations; from the stage, he’s been known to tell his fans, “Just remember, I am spending your money foolishly.”

Mihelich and Papineau gathered much of their information online. Referring to their study as a “Web ethnography,” they collected extensive narrative material from fans who joined Parrothead clubs and posted their experiences on websites. “We do not claim to have conducted a complete ethnography of Parrothead fans, or even of the Parrothead Web activity,” state the authors, “but we focused on particular aspects of Parrothead practice as revealed through Web research” (2005). Fan narratives gave them insight into how individuals identify with Buffett’s world and how fans used popular music to cultivate personal and collective meaning.

In conducting studies about pockets of culture, most sociologists seek to discover a universal appeal. Mihelich and Papineau stated, “Although Parrotheads are a relative minority of the contemporary US population, an in-depth look at their practice and conditions illuminate [sic] cultural practices and conditions many of us experience and participate in” (2005).

Here, we will look at three types of field research: participant observation, ethnography, and the case study.

Participant Observation

In participant observation research, a sociologist joins people and participates in a group’s routine activities for the purpose of observing them within that context. This method lets researchers experience a specific aspect of social life. A researcher might go to great lengths to get a firsthand look into a trend, institution, or behavior. Researchers temporarily put themselves into roles and record their observations. A researcher might work as a waitress in a diner, live as a homeless person for several weeks, or ride along with police officers as they patrol their regular beat.

Although these researchers try to blend in seamlessly with the population they study, they are still obligated to obtain IRB approval. In keeping with scholarly objectives, the purpose of their observation is different from simply “people watching” at one’s workplace, on the bus or train, or in a public space.

At the beginning of a field study, researchers might have a question: “What really goes on in the kitchen of the most popular diner on campus?” or “What is it like to experience homelessness?” Participant observation is a useful method if the researcher wants to explore a certain environment from the inside.

Field researchers simply want to observe and learn. In such a setting, the researcher will be alert and open minded to whatever happens, recording all observations accurately. Soon, as patterns emerge, questions will become more specific, observations will lead to hypotheses, and hypotheses will guide the researcher in shaping data into results.

Some sociologists prefer not to alert people to their presence. The main advantage of covert participant observation is that it allows the researcher access to authentic, natural behaviors of a group’s members. The challenge, however, is gaining access to a setting without disrupting the pattern of others’ behavior. Becoming an inside member of a group, organization, or subculture takes time and effort. Researchers must pretend to be something they are not. The process could involve role playing, making contacts, networking, or applying for a job. Whenever deception is involved in sociological research, it will be intensely scrutinized and may or may not be approved by an institutional IRB.

Once inside a group, participation observation research can last months or even years. Sociologists have to balance the types of interpersonal relationships that arise from living and/or working with other people with objectivity as a researcher. They must keep their purpose in mind and apply the sociological perspective. That way, they illuminate social patterns that are often unrecognized. Because information gathered during participant observation is mostly qualitative, rather than quantitative, the end results are often descriptive or interpretive. This type of research is well-suited to learning about the kinds of human behavior or social groups that are not known by the scientific community, who are particularly closed or secretive, or when one is attempting to understand societal structures, as we will see in the following example.

Nickel and Dimed (2001, 2011)

Journalist Barbara Ehrenreich conducted participation observation research for her book Nickel and Dimed. One day over lunch with her editor, Ehrenreich mentioned an idea. How can people exist on minimum-wage work? How do low-income workers get by? she wondered aloud. Someone should do a study. To her surprise, her editor responded, Why don’t you do it?

That’s how Ehrenreich found herself joining the ranks of the working class. For several months, she left her comfortable home and lived and worked among people who lacked, for the most part, higher education and marketable job skills. Undercover, she applied for and worked minimum wage jobs as a waitress, a cleaning woman, a nursing home aide, and a retail chain employee. During her participant observation, she used only her income from those jobs to pay for food, clothing, transportation, and shelter.

She discovered the obvious, that it’s almost impossible to get by on minimum wage service work. She also experienced and observed attitudes many middle and upper-class people never think about. She witnessed firsthand the treatment of working class employees. She saw the extreme measures people take to make ends meet and to survive. She described fellow employees who held two or three jobs, worked seven days a week, lived in cars, could not pay to treat chronic health conditions, got randomly fired, submitted to drug tests, and moved in and out of homeless shelters. She brought aspects of that life to light, describing difficult working conditions and the poor treatment that low-wage workers suffer.

Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting By in America, the book she wrote upon her return to her real life as a well-paid writer, has been widely read and used in many college classrooms. The first edition was published in 2001 and a follow-up post-recession edition was published with updated information in 2011.

Ethnography

Ethnography is a type of social research that involves the extended observation of the social perspective and cultural values of an entire social setting. Ethnographies involve objective observation of an entire community, and they often involve participant observation as a research method.

British anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski, who studied the Trobriand Islanders near Papua New Guinea during World War I, was one of the first anthropologists to engage with the communities they studied and he became known for this methodological contribution, which differed from the detached observations that took place from a distance (i.e., “on the verandas” or “armchair anthropology”).

Although anthropologists had been doing ethnographic research longer, sociologists were doing ethnographic research in the 20th century, particularly in what became known as The Chicago School at the University of Chicago. William Foote Whyte’s Street Corner Society: The Social Structure of an Italian Slum (1943) is a seminal work of urban ethnography and a “classic” sociological text.

The heart of an ethnographic study focuses on how subjects view their own social standing and how they understand themselves in relation to a community. An ethnographic study might observe, for example, a small U.S. fishing town, an Inuit community, a village in Thailand, a Buddhist monastery, a private boarding school, or an amusement park. These places all have borders. People live, work, study, or vacation within those borders. People are there for a certain reason and therefore behave in certain ways and respect certain cultural norms. An ethnographer would commit to spending a predetermined amount of time studying every aspect of the chosen place, taking in as much as possible.

A sociologist studying a tribe in the Amazon might watch the way villagers go about their daily lives and then write a paper about it. To observe a spiritual retreat center, an ethnographer might attend as a guest for an extended stay, observe and record data, and collate the material into results.

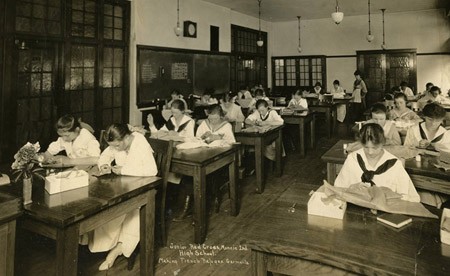

The Making of Middletown: A Study in Modern U.S. Culture

In 1924, a young married couple named Robert and Helen Lynd undertook an unprecedented ethnography: to apply sociological methods to the study of one U.S. city in order to discover what “ordinary” people in the United States did and believed. Choosing Muncie, Indiana (population about 30,000), as their subject, they moved to the small town and lived there for eighteen months.

Ethnographers had been examining other cultures for decades—groups considered minority or outsider—like gangs, immigrants, and the poor. But no one had studied the so-called average American.

Recording interviews and using surveys to gather data, the Lynds did not sugarcoat or idealize U.S. life (PBS). They objectively stated what they observed. Researching existing sources, they compared Muncie in 1890 to the Muncie they observed in 1924. Most Muncie adults, they found, had grown up on farms but now lived in homes inside the city. From that discovery, the Lynds focused their study on the impact of industrialization and urbanization.

They observed that the workers of Muncie were divided into business class and working class groups. They defined business class as dealing with abstract concepts and symbols, while working class people used tools to create concrete objects. The two classes led different lives with different goals and hopes. However, the Lynds observed, mass production offered both classes the same amenities. Like wealthy families, the working class was now able to own radios, cars, washing machines, telephones, vacuum cleaners, and refrigerators. This was a newly emerging economic and material reality of the 1920s.

As the Lynds worked, they divided their manuscript into six sections: Getting a Living, Making a Home, Training the Young, Using Leisure, Engaging in Religious Practices, and Engaging in Community Activities. Each chapter included subsections such as “The Long Arm of the Job” and “Why Do They Work So Hard?” in the “Getting a Living” chapter.

When the study was completed, the Lynds encountered a big problem. The Rockefeller Foundation, which had commissioned the book, claimed it was useless and refused to publish it. The Lynds asked if they could seek a publisher themselves.

As it turned out, Middletown: A Study in Modern American Culture was not only published in 1929, but also became an instant bestseller, a status unheard of for a sociological study. The book sold out six printings in its first year of publication, and has never gone out of print (PBS).

Nothing like it had ever been done before. Middletown was reviewed on the front page of the New York Times. Readers in the 1920s and 1930s identified with the citizens of Muncie, Indiana, but they were equally fascinated by the sociological methods and the use of scientific data to define ordinary people in the United States. The book was proof that social data were important—and interesting—to the U.S. public.

Institutional Ethnography

Institutional ethnography is an extension of basic ethnographic research principles that focuses intentionally on everyday concrete social relationships. Developed by Canadian sociologist Dorothy E. Smith, institutional ethnography is often considered a feminist-inspired approach to social analysis and primarily considers women’s experiences within male-dominated societies and power structures. Smith’s work challenges sociology’s exclusion of women, both academically and in the study of women’s lives (Fenstermaker, n.d.).

Historically, social science research tended to objectify women and ignore their experiences except as viewed from a male perspective. Modern feminists note that describing women, and other marginalized groups, as subordinates helps those in authority maintain their own dominant positions (Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, n.d.). Smith’s three major works explored what she called “the conceptual practices of power” (1990; cited in Fensternmaker, n.d.) and are still considered seminal works in feminist theory and ethnography.

Try It

Case Study

Sometimes a researcher wants to study one specific person or event. A case study is an in-depth analysis of a single event, situation, or individual. To conduct a case study, a researcher examines existing sources like documents and archival records, conducts interviews, or engages in direct observation and even participant observation, if possible.

Researchers might use this method to study a single case of, for example, a foster child, drug lord, cancer patient, criminal, or rape victim. However, a major criticism of the case study method is that a developed study of a single case, while offering depth on a topic, does not provide broad enough evidence to form a generalized conclusion. In other words, it is difficult to make universal claims based on just one person, since one person does not verify a pattern. This is why most sociologists do not use case studies as a primary research method.

However, case studies are useful when the single case is unique. In these instances, a single case study can add tremendous knowledge to a certain discipline. For example, a feral child, also called a “wild child,” is one who grows up isolated from other human beings. Feral children grow up without social contact and language, which are elements crucial to a “civilized” child’s development. These children mimic the behaviors and movements of animals, and often invent their own language. There are only about one hundred cases of “feral children” in the world.

As you may imagine, a feral child is a subject of great interest to researchers. Feral children provide unique information about child development because they have grown up outside of the parameters of “normal” child socialization and language acquisition. And since there are very few feral children, the case study is the most appropriate method for researchers to use in studying the subject.

At age three, a Ukranian girl named Oxana Malaya suffered severe parental neglect. She lived in a shed with dogs, and she ate raw meat and scraps. Five years later, a neighbor called authorities and reported seeing a girl who ran on all fours, barking. Officials brought Oxana into society, where she was cared for and taught some human behaviors, but she never became fully socialized. She has been designated as unable to support herself and now lives in a mental institution (Grice 2011). Case studies like this offer a way for sociologists to collect data that may not be collectable by any other method.

Try It

Glossary

- case study:

- in-depth analysis of a single event, situation, or individual

- ethnography:

- observing a complete social setting and all that it entails

- field research:

- gathering data from a natural environment without doing a lab experiment or a survey

- participant observation:

- when a researcher immerses herself in a group or social setting in order to make observations from an “insider” perspective

- primary data:

- data that are collected directly from firsthand experience

<a style="margin-left: 16px;" target="_blank" href="https://docs.google.com/document/d/1vy-T6DtTF-BbMfpVEI7VP_R7w2A4anzYZLXR8Pk4Fu4"