9.3 Measuring Entropy and Entropy Changes

Learning Objectives

- To gain an understanding of methods of measuring entropy and entropy change.

As the temperature of a sample decreases, its kinetic energy decreases and, correspondingly, the number of microstates possible decreases. The third law of thermodynamics states: at absolute zero (0 K), the entropy of a pure, perfect crystal is zero. In other words, at absolute zero, there is only one microstate and according to Boltzmann’s equation:

S = k ln W = k ln 1 = 0

Using this as a reference point, the entropy of a substance can be obtained by measuring the heat required to raise the temperature a given amount, using a reversible process. Reversible heating requires very slow and very small increases in heat.

ΔS = ![]()

Example 1

Determine the change in entropy (in J/K) of water when 425 kJ of heat is applied to it at 50oC. Assume the change is reversible and the temperature remains constant.

Solution

ΔS = ![]() =

= ![]() =

= ![]() = 1.32 x

= 1.32 x

![]()

J/K

Standard Molar Entropy, So

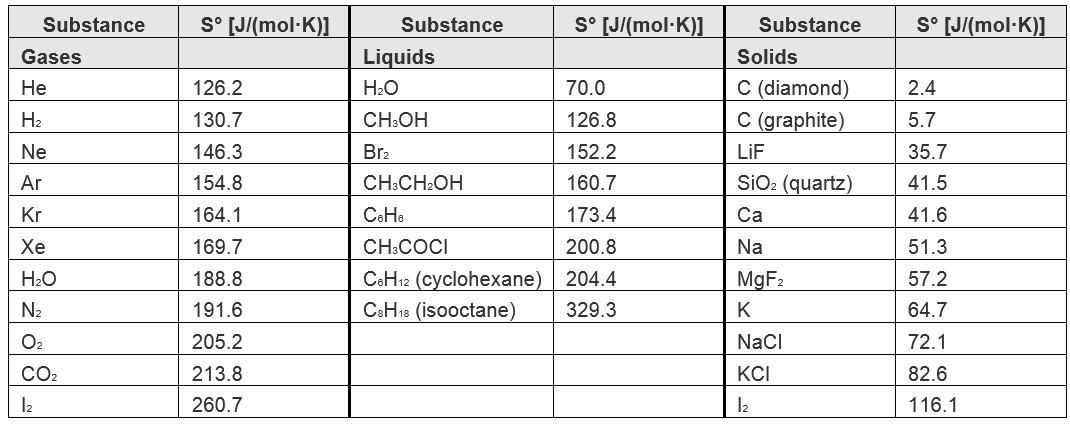

The standard molar entropy, So, is the entropy of 1 mole of a substance in its standard state, at 1 atm of pressure. These values have been tabulated, and selected substances are listed in Table 9.1 “Standard Molar Entropies of Selected Substances at 298 K.”[1]

Several trends emerge from standard molar entropy data:

- Larger, more complex molecules have higher standard molar entropy values than smaller or simpler molecules. There are more possible arrangements of atoms in space for larger, more complex molecules, increasing the number of possible microstates.

- Gases tend to have much larger standard molar entropies than liquids, and liquids tend to have larger values than solids, when comparing the same or similar substances.

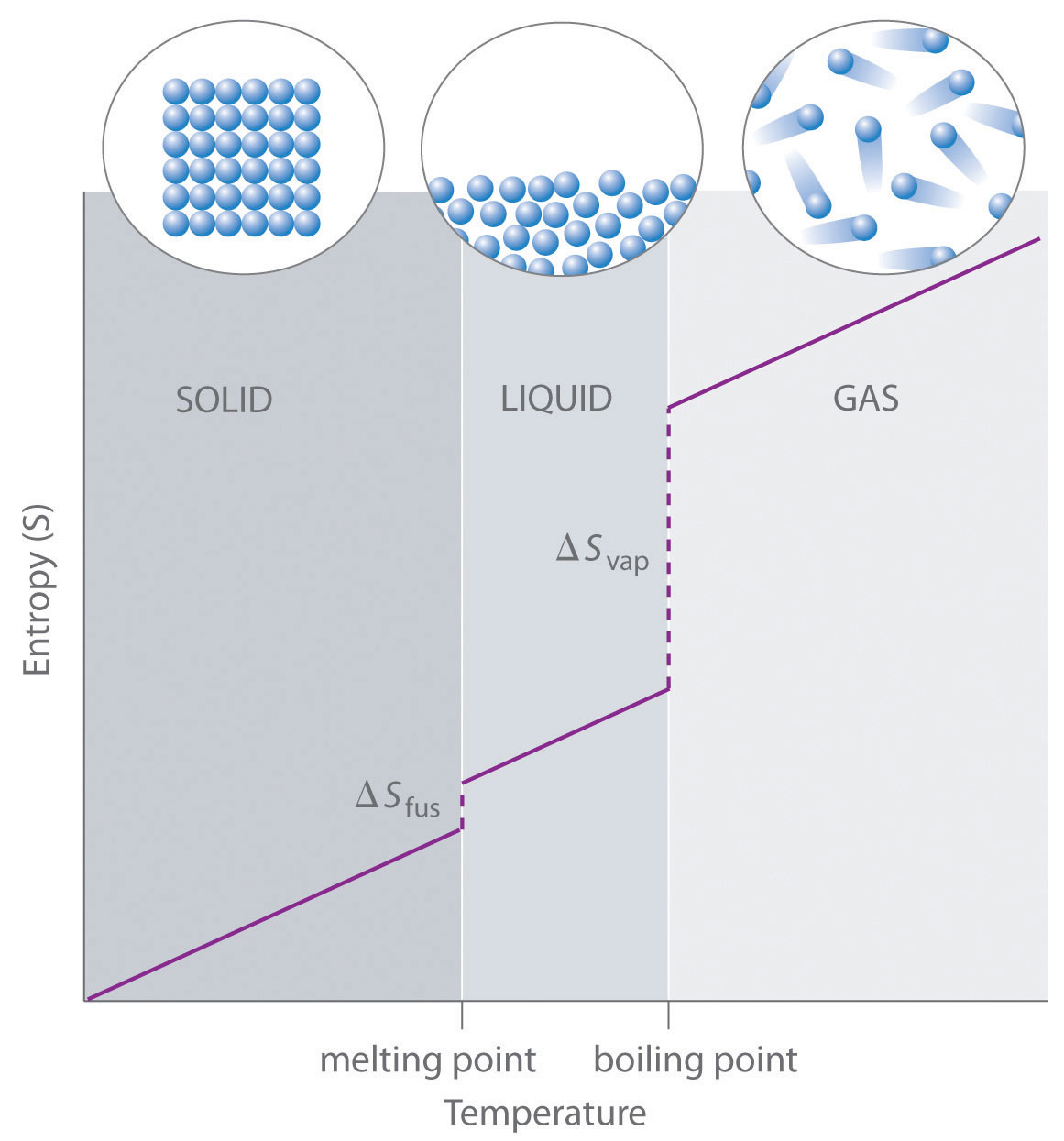

- The standard molar entropy of any substance increases as the temperature increases. This can be seen in Figure 9.3 “Entropy vs. Temperature of a Single Substance.” Large jumps in entropy occur at the phase changes: solid to liquid and liquid to gas. These large increases occur due to sudden increased molecular mobility and larger available volumes associated with the phase changes.

Standard Entropy Change of a Reaction, ΔS⁰

The entropy change of a reaction where the reactants and products are in their standard state can be determined using the following equation:

ΔS⁰ = ∑nS⁰(products) – ∑mS⁰(reactants)

where n and m are the coefficients found in the balanced chemical equation of the reaction.

Example 2

Determine the change in the standard entropy, ΔS⁰, for the synthesis of carbon dioxide from graphite and oxygen:

C(s) + O2(g) → CO2(g)

Solution

ΔS⁰ = ∑nS⁰(products) – ∑mS⁰(reactants)

ΔS⁰ = (213.8 J/mol K) – (205.2 J/mol K + 5.7 J/mol K)

ΔS⁰ = +2.9 J/mol K

Entropy Changes in the Surroundings

The second law of thermodynamics states that a spontaneous reaction will result in an increase of entropy in the universe. The universe comprises both the system being examined and its surroundings.

ΔSuniverse = ΔSsys + ΔSsurr

Standard entropy change can also be calculated by the following:

ΔS⁰universe = ΔS⁰sys + ΔS⁰surr

The change in entropy of the surroundings is essentially just a measure of how much energy is being taken in or given off by the system. Under isothermal conditions, we can express the entropy change of the surroundings as:

ΔSsurr = ![]() or ΔSsurr =

or ΔSsurr = ![]() (at constant pressure)

(at constant pressure)

Example 3

For the previous example, the change in the standard entropy, ΔS⁰, for the synthesis of carbon dioxide from graphite and oxygen, use the previously calculated ΔS⁰sys and standard enthalpy of formation values to determine S⁰surr and ΔS⁰universe.

Solution

First we should solve for the ΔH⁰sys using the standard enthalpies of formation values:

ΔH⁰sys = ΔH⁰f [CO2(g)] – ΔH⁰f [C(s) + O2(g)]

ΔH⁰sys = (-393.5 kJ/mol) – (0 kJ/mol + 0 kJ/mol)

ΔH⁰sys = -393.5 kJ/mol

Now we can convert this to the ΔS⁰surr:

ΔS⁰surr = ![]() = (-393.5 kJ/mol)/(298 K) = -1.32 kJ/mol K

= (-393.5 kJ/mol)/(298 K) = -1.32 kJ/mol K

Finally, solve for ΔS⁰universe:

ΔS⁰universe = ΔS⁰sys + ΔS⁰surr

ΔS⁰universe = (+2.9 J/mol K) + (-1.32 x 103 J/mol K)

ΔS⁰universe = -1.3 x 103 J/mol K

Key Takeaways

- At absolute zero (0 K), the entropy of a pure, perfect crystal is zero.

- The entropy of a substance can be obtained by measuring the heat required to raise the temperature a given amount, using a reversible process.

- The standard molar entropy, So, is the entropy of 1 mole of a substance in its standard state, at 1 atm of pressure.

- Courtesy UC Davis ChemWiki by University of California\CC-BY-SA-3.0 ↵