Reading: Institutional Factors Shaping the Global Marketing Environment

The Influence of Government and Regulations on Global Marketing

Political Stability

Business activity tends to grow and thrive when a nation is politically stable. When a nation is politically unstable, multinational firms can still conduct business profitably, but there are higher risks and often higher costs associated with business operations. Political instability makes a country less attractive from a business investment perspective, so foreign and domestic companies doing business there frequently must pay higher interest rates on business loans, higher insurance rates, and often higher costs to protect the security of their employees and operations. Alternatively, in countries with stable political environments, the behaviour of consumers and markets is more predictable, and organizations can rely on governments enforcing the rule of law, meaning that governments do not exercise power arbitrarily. Instead, they adhere to established, recognized, and well-defined laws.

Domestic and Global Business Law

Governments around the world maintain laws that regulate business practices. In some nations, these laws are more heavy-handed, and in other countries, the environment for business is more freewheeling or self-regulating. As we reviewed in Chapter 5, there are many legal and ethical considerations from a marketers perspective. There are even laws and regulations that affect what marketers are allowed to include in marketing communications, although these are far more strict in some countries than in others.

Marketers should become familiar with the political and regulatory environments in the countries and world regions where they operate, and specifically the laws, regulations, and legal processes that may affect business and marketing operations. For example, it is common for countries to maintain laws and regulations in the following areas:

- Contract law governing agreements about the supply and delivery of goods and services

- Trademark registration and enforcement for brand names, logos, tag lines, and so forth

- Labeling for the purposes of consumer safety, protection, and transparency

- Patents to enforce intellectual property rights and business rights associated with unique inventions and “ownable” business ideas

- Decency, censorship, and freedom-of-expression laws to which marketing communications are subject

- Price floors, ceilings, and other regulations regarding the prices organizations can charge for some types of goods and services

- Product safety, testing, and quality control

- Environmental protection, conservation, and the use of permits and other regulatory tools to encourage acceptable and responsible business practices

- Privacy, including laws governing data collection, storage, use, and permissions associated with consumers and their digital identities

- Financial reporting and disclosure to ensure that organizations provide transparency around using sound business and financial practices

In some cases, international laws and regulations also seek to govern these issues, looking out for ways to manage the friction that can surface between national governments, as well as ways to serve the common interests of regional allies and economic partners.

Free Trade and Protectionism

Free trade refers to the free exchange of goods and services across international borders without governmental restrictions such as quotas (which limit amounts of goods that can be traded), tariffs (which are taxes charged for imported or exported goods), and other restrictions. Many nations encourage free trade by inviting foreign firms to invest in and conduct business without severe disadvantages or restrictions compared to domestic businesses. Often these same governments encourage domestic firms to engage in overseas business. When governments have a strong free-trade orientation, they typically prefer not to enact regulations that strictly limit imports and discriminate against foreign firms–at least not in most product and service categories. When countries enact free trade agreements (FTA) with one another, they agree to allow advantageous terms for the flow of goods and services between designated countries. Regional trading blocs represent a group of nations that join together and formally agree to reduce trade barriers among themselves. Trading relationships across the world have changed dramatically since 2016.

A new trading agreement was struck to update the 20-year-old North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). The Canada-United States-Mexico Agreement CUSMA enacted in 2019 boosts export sales between these countries by enabling companies to sell goods at lower prices because tariffs are reduced or eliminated.

Watch the Government of Canada video CUSMA – Prosperity Through Trade.

Canada’s largest trading partners are[1]:

| Country | Export Value ($B) |

| United States | $443 billion |

| European Union | $50 billion |

| China | $24 billion |

| Japan | $13 billion |

| Mexico | $8.4 billion |

The European Union (EU) Single Market attempts to guarantee free trade between the twenty-eight member states of the European Union. In 2016, U.K. citizens voted by referendum to exit from the EU — well known as Brexit. This has destabilized the EU. Britain voted to exit the EU in 2019. One-third of all EU trade was with the US and China.

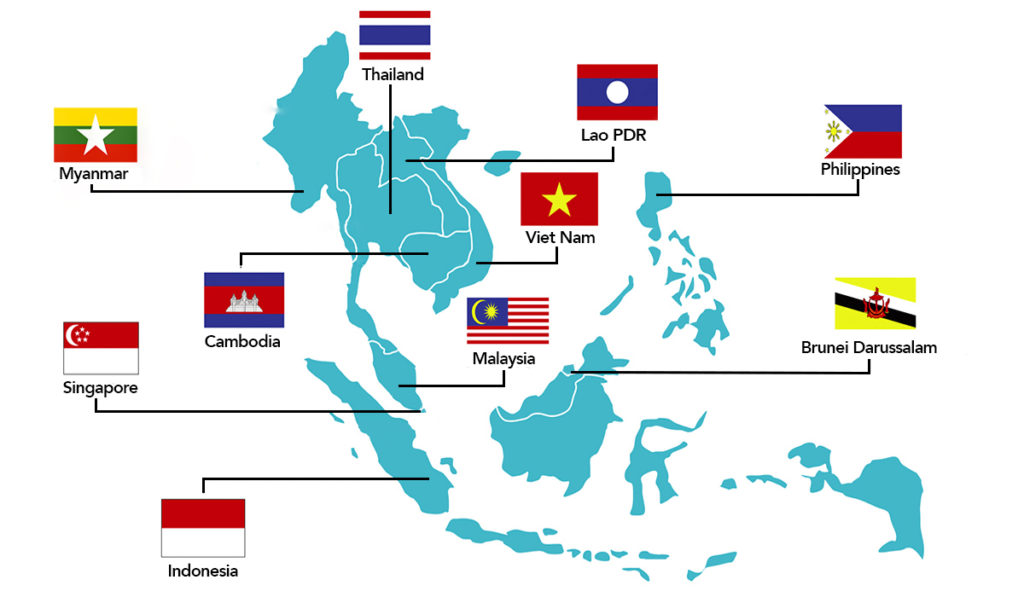

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) is an example of a regional trading block. This agreement allows for the free exchange of trade, service, labor, and capital across the ten independent member nations, including Canada. In addition, ASEAN promotes the regional integration of transportation and energy infrastructure.

The Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) is a free trade agreement between Canada and 10 other countries in the Asia-Pacific region: Australia, Brunei, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, and Vietnam. The CPTPP strategically sets the terms of trade in the Asia-Pacific region. CPTPP Agreement, along with CUSMA and free trade agreements with the Canada- European Union, Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) and South Korea, makes Canada the only Group of 7 (G7) nation with free trade access to the Americas, Europe and the Asia-Pacific region.

Almost all the countries in the Western hemisphere have entered into one or more regional trade agreements. Such agreements are designed to facilitate trade through the establishment of a free-trade area, customs union, or customs market.

Governments engage in protectionism when they enact policies that privilege domestic industries and businesses over those based in foreign countries. Protectionist policies may enact quotas that strictly limit the numbers of imported or exported goods allowed. Quotas are designed to prevent foreign imports from meeting all the demand for a product; instead, they carve out room for domestic suppliers to meet some of this demand. Another common protectionist policy is to levy tariffs that restrict trade by placing taxes on imported goods to make them more expensive in the domestic market. Protective tariffs are frequently established to protect domestic manufacturers against competitors by raising the prices of imported goods. For example, in June 2018, the United States imposed import tariffs of 25% on Canadian steel products and 10% on Canadian aluminum products. In June 2019, the first month after tariffs were lifted, exports of steel products to the United States grew by 15.8%[2]

Expropriation

All multinational firms face the risk of expropriation. Expropriation takes place when a government takes ownership of property or business operations such as real estate, manufacturing plants, or other assets, sometimes without compensating the owners. In many expropriations of foreign business property by domestic governments, there have been payments, and it is often equitable. Because of the risk of expropriation, multinational firms are at the mercy of foreign governments, which are sometimes unstable and can change the laws they enforce at any point to meet their needs.

Trade Policy and the World Trade Organization

Countries engage in international trade for two basic reasons, each of which contributes to the country’s gain from trade. First, countries trade because they are different from one another. Nations can benefit from their differences by reaching agreements in which each party contributes its strengths and focuses on producing goods efficiently. Second, countries trade to achieve economies of scale in production. While international trade has been present throughout much of history, its economic, social, and political importance have increased in recent centuries, mainly because of industrialization, advanced transportation, globalization, multinational corporations, and outsourcing.

The World Trade Organization (WTO) was formed to supervise and liberalize international trade on January 1, 1995, under the Marrakech Agreement. The organization deals with the regulation of trade between participating countries. It provides a framework for negotiating and formalizing trade agreements and a dispute resolution process aimed at enforcing participants’ adherence to WTO agreements.

Trade Sanctions and Barriers

Trade sanctions are penalties imposed on one country by one or more other countries. Allied countries may impose sanctions on their enemies. On occasion, the WTO authorizes trade sanctions against a specific country in order to punish that country for some action.

Although there are usually few trade restrictions within countries, international trade is usually regulated by governmental quotas and restrictions and often taxed by tariffs. Tariffs are usually on imports, but sometimes countries may impose export tariffs or subsidies. All of these are called trade barriers, which are established by a government that implements a protectionist policy. If a government removes all trade barriers, a condition of free trade exists. The WTO helps arbitrate and settle disputes about trade barriers between different countries.

Fair Trade

The fair trade movement promotes the use of labor, environmental, and social standards for the production of commodities, particularly those exported from developing countries to industrialized nations. Importing firms voluntarily adhere to fair trade standards, or governments may enforce them through a combination of employment and commercial law. Proposed and practiced fair trade policies vary widely, ranging from the common prohibition of goods made using slave labor to minimum-price support schemes such as those for coffee in the 1980s, to industry-focused marketing schemes to boost consumer demand for fair trade products. Nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) also play a role in promoting fair trade standards by serving as independent monitors of compliance with fair trade labeling requirements. Today fair trade certification processes inspect grower and manufacturer facilities to confirm that ethical practices are in place, and participating organizations are authorized to market their products using an increasingly visible “Fairtrade” certification mark.

A Case in Point: China

China offers an interesting and current example of the effects of political, regulatory, and trade policy on economic growth and the business environment. Beginning around 1978, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) began an experiment in economic reform. In contrast to the previous Soviet-style, centrally planned economy, the new measures progressively relaxed restrictions on farming, agricultural distribution, and, several years later, urban enterprises and labor.

China’s more market-oriented approach reduced inefficiencies and stimulated private investment, particularly by farmers, which led to increased productivity and output. The reforms proved successful in terms of increased output, variety, quality, price, and demand. In real terms, the economy doubled in size between 1978 and 1986. By 2008, the economy was 16.7 times the size it was in 1978, and 12.1 times its previous per capita levels. Since 2010, China’s economy has grown an exceptional minimum of 6% or greater per capital to 2019.

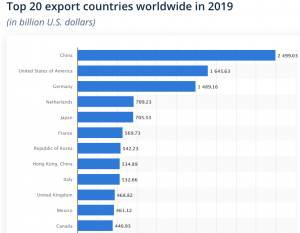

International trade progressed even more rapidly, doubling every 4.5 years on average. In 1991, the PRC joined the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation group, a trade-promotion forum. Total two-way trade in January 1998 exceeded that for all of 1978. In 2001, China joined the World Trade Organization. In 2007, China surpassed the U.S. in exports, and in 2009, China surpassed Germany to become the world’s leading exporter. [3] Today, Canadian companies must compete with Chinese imports as a reality of doing business, but also have easier access to China’s labor force and natural resources as an option in sourcing. For many companies manufacturing relationships with China and sales opportunities in China have led to efficiencies and new market opportunities.

- Global Affairs Canada. (2020). Canada's State of Trade 2020. https://www.international.gc.ca/gac-amc/publications/economist-economiste/state-of-trade-commerce-international-2020.aspx?lang=eng ↵

- Statistics Canada. (2019, August 2). Impact of recent tariffs on Canada's merchandise trade. The Daily. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/190802/dq190802b-eng.htm ↵

- World Trade Organization. (2016). International Trade Statistics 2015. https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/statis_e/its2015_e/its2015_e.pdf ↵