Freud and the Psychodynamic Perspective

Learning Objectives

- Describe the assumptions of the psychodynamic perspective on personality development, including the id, ego, and superego

- Define and describe the defense mechanisms

- Define and describe the psychosexual stages of personality development

Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) is probably the most controversial and misunderstood psychological theorist. When reading Freud’s theories, it is important to remember that he was a medical doctor, not a psychologist. There was no such thing as a degree in psychology at the time that he received his education, which can help us understand some of the controversy over his theories today. However, Freud was the first to systematically study and theorize the workings of the unconscious mind in the manner that we associate with modern psychology.

In the early years of his career, Freud worked with Josef Breuer, a Viennese physician. During this time, Freud became intrigued by the story of one of Breuer’s patients, Bertha Pappenheim, who was referred to by the pseudonym Anna O. (Launer, 2005). Anna O. had been caring for her dying father when she began to experience symptoms such as partial paralysis, headaches, blurred vision, amnesia, and hallucinations (Launer, 2005). In Freud’s day, these symptoms were commonly referred to as hysteria. Anna O. turned to Breuer for help. He spent 2 years (1880–1882) treating Anna O. and discovered that allowing her to talk about her experiences seemed to bring some relief of her symptoms. Anna O. called his treatment the “talking cure” (Launer, 2005). Despite the fact the Freud never met Anna O., her story served as the basis for the 1895 book, Studies on Hysteria, which he co-authored with Breuer. Based on Breuer’s description of Anna O.’s treatment, Freud concluded that hysteria was the result of sexual abuse in childhood and that these traumatic experiences had been hidden from consciousness. Breuer disagreed with Freud, which soon ended their work together. However, Freud continued to work to refine talk therapy and build his theory on personality.

Levels of Consciousness

To explain the concept of conscious versus unconscious experience, Freud compared the mind to an iceberg (Figure 1). He said that only about one-tenth of our mind is conscious, and the rest of our mind is unconscious. Our unconscious refers to that mental activity of which we are unaware and are unable to access (Freud, 1923). According to Freud, unacceptable urges and desires are kept in our unconscious through a process called repression. For example, we sometimes say things that we don’t intend to say by unintentionally substituting another word for the one we meant. You’ve probably heard of a Freudian slip, the term used to describe this. Freud suggested that slips of the tongue are actually sexual or aggressive urges, accidentally slipping out of our unconscious. Speech errors such as this are quite common. Seeing them as a reflection of unconscious desires, linguists today have found that slips of the tongue tend to occur when we are tired, nervous, or not at our optimal level of cognitive functioning (Motley, 2002).

According to Freud, our personality develops from a conflict between two forces: our biological aggressive and pleasure-seeking drives versus our internal (socialized) control over these drives. Our personality is the result of our efforts to balance these two competing forces. Freud suggested that we can understand this by imagining three interacting systems within our minds. He called them the id, ego, and superego (Figure 2).

The unconscious id contains our most primitive drives or urges, and is present from birth. It directs impulses for hunger, thirst, and sex. Freud believed that the id operates on what he called the “pleasure principle,” in which the id seeks immediate gratification. Through social interactions with parents and others in a child’s environment, the ego and superego develop to help control the id. The superego develops as a child interacts with others, learning the social rules for right and wrong. The superego acts as our conscience; it is our moral compass that tells us how we should behave. It strives for perfection and judges our behavior, leading to feelings of pride or—when we fall short of the ideal—feelings of guilt. In contrast to the instinctual id and the rule-based superego, the ego is the rational part of our personality. It’s what Freud considered to be the self, and it is the part of our personality that is seen by others. Its job is to balance the demands of the id and superego in the context of reality; thus, it operates on what Freud called the “reality principle.” The ego helps the id satisfy its desires in a realistic way.

The id and superego are in constant conflict, because the id wants instant gratification regardless of the consequences, but the superego tells us that we must behave in socially acceptable ways. Thus, the ego’s job is to find the middle ground. It helps satisfy the id’s desires in a rational way that will not lead us to feelings of guilt. According to Freud, a person who has a strong ego, which can balance the demands of the id and the superego, has a healthy personality. Freud maintained that imbalances in the system can lead to neurosis (a tendency to experience negative emotions), anxiety disorders, or unhealthy behaviors. For example, a person who is dominated by their id might be narcissistic and impulsive. A person with a dominant superego might be controlled by feelings of guilt and deny themselves even socially acceptable pleasures; conversely, if the superego is weak or absent, a person might become a psychopath. An overly dominant superego might be seen in an over-controlled individual whose rational grasp on reality is so strong that they are unaware of their emotional needs, or, in a neurotic who is overly defensive (overusing ego defense mechanisms).

Defense Mechanisms

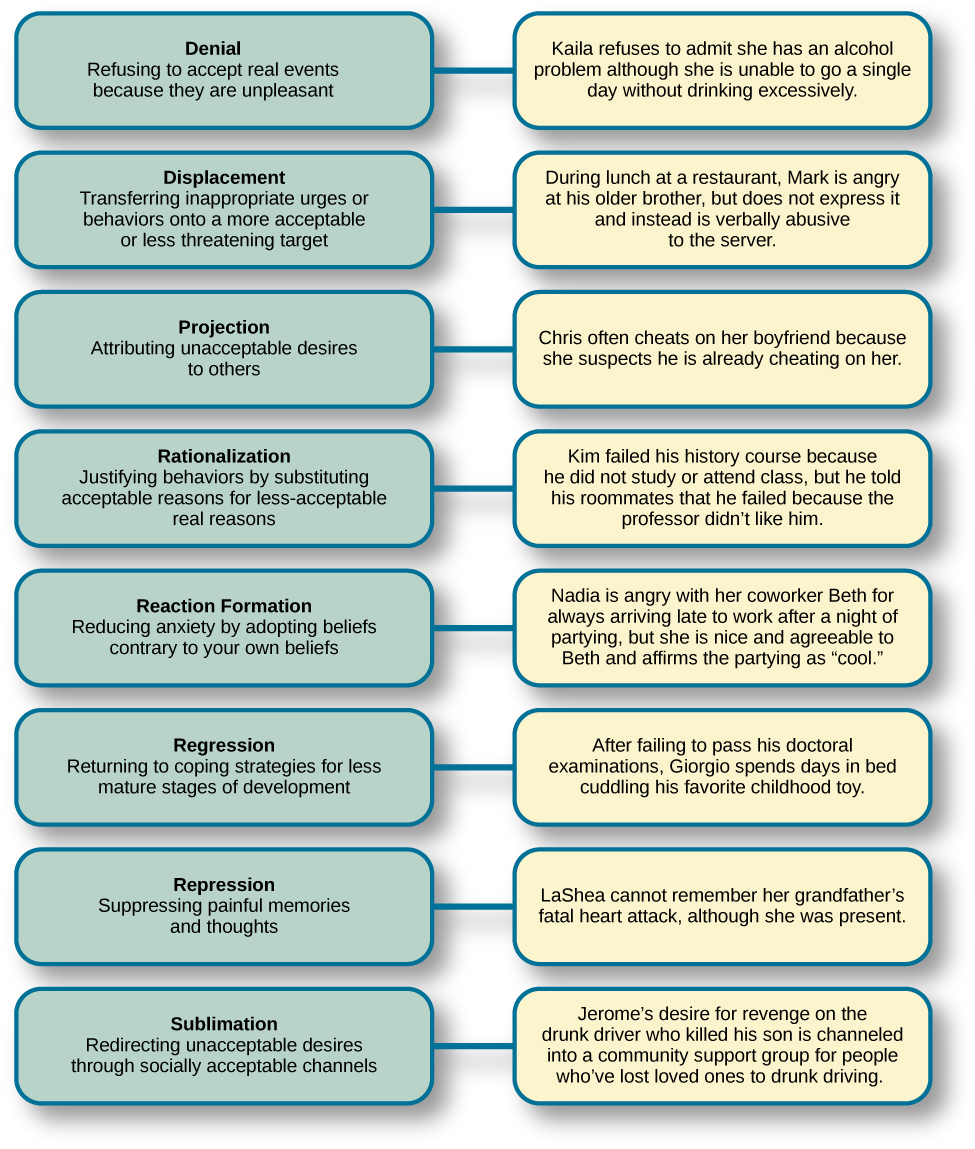

Freud believed that feelings of anxiety result from the ego’s inability to mediate the conflict between the id and superego. When this happens, Freud believed that the ego seeks to restore balance through various protective measures known as defense mechanisms (Figure 3). When certain events, feelings, or yearnings cause an individual anxiety, the individual wishes to reduce that anxiety. To do that, the individual’s unconscious mind uses ego defense mechanisms, unconscious protective behaviors that aim to reduce anxiety. The ego, usually conscious, resorts to unconscious strivings to protect the ego from being overwhelmed by anxiety. When we use defense mechanisms, we are unaware that we are using them. Further, they operate in various ways that distort reality. According to Freud, we all use ego defense mechanisms.

While everyone uses defense mechanisms, Freud believed that overuse of them may be problematic. For example, let’s say Joe Smith is a high school football player. Deep down, Joe feels sexually attracted to males. His conscious belief is that being gay is immoral and that if he were gay, his family would disown him and he would be ostracized by his peers. Therefore, there is a conflict between his conscious beliefs (being gay is wrong and will result in being ostracized) and his unconscious urges (attraction to males). The idea that he might be gay causes Joe to have feelings of anxiety. How can he decrease his anxiety? Joe may find himself acting very “macho,” making gay jokes, and picking on a school peer who is gay. This way, Joe’s unconscious impulses are further submerged.

There are several different types of defense mechanisms. For instance, in repression, anxiety-causing memories from consciousness are blocked. As an analogy, let’s say your car is making a strange noise, but because you do not have the money to get it fixed, you just turn up the radio so that you no longer hear the strange noise. Eventually you forget about it. Similarly, in the human psyche, if a memory is too overwhelming to deal with, it might be repressed and thus removed from conscious awareness (Freud, 1920). This repressed memory might cause symptoms in other areas.

Another defense mechanism is reaction formation, in which someone expresses feelings, thoughts, and behaviors opposite to their inclinations. In the above example, Joe made fun of a homosexual peer while himself being attracted to males. In regression, an individual acts much younger than their age. For example, a four-year-old child who resents the arrival of a newborn sibling may act like a baby and revert to drinking out of a bottle. In projection, a person refuses to acknowledge her own unconscious feelings and instead sees those feelings in someone else. Other defense mechanisms include rationalization, displacement, and sublimation.

Stages of Psychosexual Development

Freud believed that personality develops during early childhood: Childhood experiences shape our personalities as well as our behavior as adults. He asserted that we develop via a series of stages during childhood. Each of us must pass through these childhood stages, and if we do not have the proper nurturing and parenting during a stage, we will be stuck, or fixated, in that stage, even as adults.

In each psychosexual stage of development, the child’s pleasure-seeking urges, coming from the id, are focused on a different area of the body, called an erogenous zone. The stages are oral, anal, phallic, latency, and genital (Table 1).

Freud’s psychosexual development theory is quite controversial. To understand the origins of the theory, it is helpful to be familiar with the political, social, and cultural influences of Freud’s day in Vienna at the turn of the 20th century. During this era, a climate of sexual repression, combined with limited understanding and education surrounding human sexuality, heavily influenced Freud’s perspective. Given that sex was a taboo topic, Freud assumed that negative emotional states (neuroses) stemmed from suppression of unconscious sexual and aggressive urges. For Freud, his own recollections and interpretations of patients’ experiences and dreams were sufficient proof that psychosexual stages were universal events in early childhood.

| Stage | Age (years) | Erogenous Zone | Major Conflict | Adult Fixation Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oral | 0–1 | Mouth | Weaning off breast or bottle | Smoking, overeating |

| Anal | 1–3 | Anus | Toilet training | Neatness, messiness |

| Phallic | 3–6 | Genitals | Oedipus/Electra complex | Vanity, overambition |

| Latency | 6–12 | None | None | None |

| Genital | 12+ | Genitals | None | None |

Oral Stage

In the oral stage (birth to 1 year), pleasure is focused on the mouth. Eating and the pleasure derived from sucking (nipples, pacifiers, and thumbs) play a large part in a baby’s first year of life. At around 1 year of age, babies are weaned from the bottle or breast, and this process can create conflict if not handled properly by caregivers. According to Freud, an adult who smokes, drinks, overeats, or bites her nails is fixated in the oral stage of her psychosexual development; she may have been weaned too early or too late, resulting in these fixation tendencies, all of which seek to ease anxiety.

Anal Stage

After passing through the oral stage, children enter what Freud termed the anal stage (1–3 years). In this stage, children experience pleasure in their bowel and bladder movements, so it makes sense that the conflict in this stage is over toilet training. Freud suggested that success at the anal stage depended on how parents handled toilet training. Parents who offer praise and rewards encourage positive results and can help children feel competent. Parents who are harsh in toilet training can cause a child to become fixated at the anal stage, leading to the development of an anal-retentive personality. The anal-retentive personality is stingy and stubborn, has a compulsive need for order and neatness, and might be considered a perfectionist. If parents are too lenient in toilet training, the child might also become fixated and display an anal-expulsive personality. The anal-expulsive personality is messy, careless, disorganized, and prone to emotional outbursts.

Phallic Stage

Freud’s third stage of psychosexual development is the phallic stage (3–6 years), corresponding to the age when children become aware of their bodies and recognize the differences between boys and girls. The erogenous zone in this stage is the genitals. Conflict arises when the child feels a desire for the opposite-sex parent, and jealousy and hatred toward the same-sex parent. For boys, this is called the Oedipus complex, involving a boy’s desire for his mother and his urge to replace his father who is seen as a rival for the mother’s attention. At the same time, the boy is afraid his father will punish him for his feelings, so he experiences castration anxiety. The Oedipus complex is successfully resolved when the boy begins to identify with his father as an indirect way to have the mother. Failure to resolve the Oedipus complex may result in fixation and development of a personality that might be described as vain and overly ambitious.

Girls experience a comparable conflict in the phallic stage—the Electra complex. The Electra complex, while often attributed to Freud, was actually proposed by Freud’s protégé, Carl Jung (Jung & Kerenyi, 1963). A girl desires the attention of her father and wishes to take her mother’s place. Jung also said that girls are angry with the mother for not providing them with a penis—hence the term penis envy. While Freud initially embraced the Electra complex as a parallel to the Oedipus complex, he later rejected it, yet it remains as a cornerstone of Freudian theory, thanks in part to academics in the field (Freud, 1931/1968; Scott, 2005).

Latency Period

Following the phallic stage of psychosexual development is a period known as the latency period (6 years to puberty). This period is not considered a stage, because sexual feelings are dormant as children focus on other pursuits, such as school, friendships, hobbies, and sports. Children generally engage in activities with peers of the same sex, which serves to consolidate a child’s gender-role identity.

Genital Stage

The final stage is the genital stage (from puberty on). In this stage, there is a sexual reawakening as the incestuous urges resurface. The young person redirects these urges to other, more socially acceptable partners (who often resemble the other-sex parent). People in this stage have mature sexual interests, which for Freud meant a strong desire for the opposite sex. Individuals who successfully completed the previous stages, reaching the genital stage with no fixations, are said to be well-balanced, healthy adults.

While most of Freud’s ideas have not found support in modern research, we cannot discount the contributions that Freud has made to the field of psychology. It was Freud who pointed out that a large part of our mental life is influenced by the experiences of early childhood and takes place outside of our conscious awareness; his theories paved the way for others.

Freud’s Theories Today

Empirical research assessing psychodynamic concepts has produced mixed results, with some concepts receiving good empirical support, and others not faring as well. For example, the notion that we express strong sexual feelings from a very early age, as the psychosexual stage model suggests, has not held up to empirical scrutiny. On the other hand, the idea that there are dependent, control-oriented, and competitive personality types—an idea also derived from the psychosexual stage model—does seem useful.

Many ideas from the psychodynamic perspective have been studied empirically. Luborsky and Barrett (2006) reviewed much of this research; other useful reviews are provided by Bornstein (2005), Gerber (2007), and Huprich (2009). For now, let’s look at three psychodynamic hypotheses that have received strong empirical support.

- Unconscious processes influence our behavior as the psychodynamic perspective predicts. We perceive and process much more information than we realize, and much of our behavior is shaped by feelings and motives of which we are, at best, only partially aware (Bornstein, 2009, 2010). Evidence for the importance of unconscious influences is so compelling that it has become a central element of contemporary cognitive and social psychology (Robinson & Gordon, 2011).

- We all use ego defenses and they help determine our psychological adjustment and physical health. People really do differ in the degree that they rely on different ego defenses—so much so that researchers now study each person’s “defense style” (the unique constellation of defenses that we use). It turns out that certain defenses are more adaptive than others: Rationalization and sublimation are healthier (psychologically speaking) than repression and reaction formation (Cramer, 2006). Denial is, quite literally, bad for your health, because people who use denial tend to ignore symptoms of illness until it’s too late (Bond, 2004).

- Mental representations of self and others do indeed serve as blueprints for later relationships.Dozens have studies have shown that mental images of our parents, and other significant figures, really do shape our expectations for later friendships and romantic relationships. The idea that you choose a romantic partner who resembles mom or dad is a myth, but it’s true that you expect to be treated by others as you were treated by your parents early in life (Silverstein, 2007; Wachtel, 1997).

Think It Over

- What are some examples of defense mechanisms that you have used yourself or have witnessed others using?

Licenses and Attributions (Click to expand)

CC licensed content, Shared previously

- Freud and the Psychodynamic Perspective. Authored by: OpenStax College. Located at: https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/11-2-freud-and-the-psychodynamic-perspective. License: CC BY: Attribution. License Terms: Download for free at https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction

- Freud’s Theories Today. Authored by: Robert Bornstein . Provided by: Adelphi University. Located at: http://nobaproject.com/modules/the-psychodynamic-perspective. Project: The Noba Project. License: CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

mental activity (thoughts, feelings, and memories) that we can access at any time

mental activity of which we are unaware and unable to access

aspect of personality that consists of our most primitive drives or urges, including impulses for hunger, thirst, and sex

aspect of the personality that serves as one’s moral compass, or conscience

aspect of personality that represents the self, or the part of one’s personality that is visible to others

tendency to experience negative emotions

unconscious protective behaviors designed to reduce ego anxiety

ego defense mechanism in which anxiety-related thoughts and memories are kept in the unconscious

ego defense mechanism in which a person confronted with anxiety swaps unacceptable urges or behaviors for their opposites

ego defense mechanism in which a person confronted with anxiety returns to a more immature behavioral state

ego defense mechanism in which a person confronted with anxiety disguises their unacceptable urges or behaviors by attributing them to other people

ego defense mechanism in which a person confronted with anxiety makes excuses to justify behavior

ego defense mechanism in which a person transfers inappropriate urges or behaviors toward a more acceptable or less threatening target

ego defense mechanism in which unacceptable urges are channeled into more appropriate activities

stages of child development in which a child’s pleasure-seeking urges are focused on specific areas of the body called erogenous zones

psychosexual stage in which an infant’s pleasure is focused on the mouth

psychosexual stage in which children experience pleasure in their bowel and bladder movements

psychosexual stage in which the focus is on the genitals

psychosexual stage in which sexual feelings are dormant

psychosexual stage in which the focus is on mature sexual interests