Developing Employees

Developing Employees

Because companies can’t survive unless employees do their jobs well, it makes economic sense to train them and develop their skills. This type of support begins when an individual enters the organization and continues as long as he or she stays there.

New-Employee Orientation

Have you ever started your first day at a new job feeling upbeat and optimistic only to walk out at the end of the day thinking that maybe you’ve taken the wrong job? If this happens too often, your employer may need to revise its approach to orientation—the way it introduces new employees to the organization and their jobs. Starting a new job is a little like beginning college; at the outset, you may be experiencing any of the following feelings:

- Somewhat nervous but enthusiastic

- Eager to impress but not wanting to attract too much attention

- Interested in learning but fearful of being overwhelmed with information

- Hoping to fit in and worried about looking new or inexperienced[1]

The employer who understands how common such feelings are is more likely not only to help newcomers get over them but also to avoid the pitfalls often associated with new-employee orientation:

- Failing to have a workspace set up for you

- Ignoring you or failing to supervise you

- Neglecting to introduce you to coworkers

- Swamping you with facts about the company[2]

A good employer will take things slowly, providing you with information about the company and your job on a need-to-know basis while making you feel as comfortable as possible. You’ll get to know the company’s history, traditions, policies, and culture over time. You’ll learn more about salary and benefits and how your performance will be evaluated. Most importantly, you’ll find out how your job fits into overall operations and what’s expected of you.

Training and Development

It would be nice if employees came with all the skills they need to do their jobs. It would also be nice if job requirements stayed the same: once you’ve learned how to do a job, you’d know how to do it forever. In reality, new employees must be trained; moreover, as they grow in their jobs or as their jobs change, they’ll need additional training. Unfortunately, training is costly and time-consuming. How costly? The Conference Board of Canada reported that Canadian companies spent $688 per employee for training in 2010.

Many Canadian companies focus much of their training on diversity skills. What’s the payoff? They create a more inclusive workplace and bring new voices and ideas to their way of doing business. Some of these companies also get additional rewards by being recognized as being Canada’s Best Diversity Employers.[3] At Booz Allen Hamilton, consultants specialize in finding innovative solutions to client problems, and their employer makes sure that they’re up-to-date on all the new technologies by maintaining a “technology petting zoo” at its training headquarters. It’s called a “petting zoo” because employees get to see, touch, and interact with new and emerging technologies. For example, a Washington Post reporter visiting the “petting zoo” in 2007 saw fabric that could instantly harden if struck by a knife or bullet, and “smart” clothing that could monitor a wearer’s health or environment.[4]

At Booz Allen Hamilton’s technology “petting zoo,” employees are receiving off-the-job training. This approach allows them to focus on learning without the distractions that would occur in the office. More common, however, is informal on-the-job training, which may be supplemented with formal training programs. This is the method, for example, by which you’d move up from mere coffee maker to a full-fledged “barista” if you worked at Starbucks.[5] You’d begin by reading a large spiral book (titled Starbucks University) on the responsibilities of the barista, pass a series of tests on the reading, then get hands-on experience in making drinks, mastering one at a time.[6] Doing more complex jobs in business will likely require even more training than is required to be a barista.

Equity, Inclusion, and Diversity in the Workplace

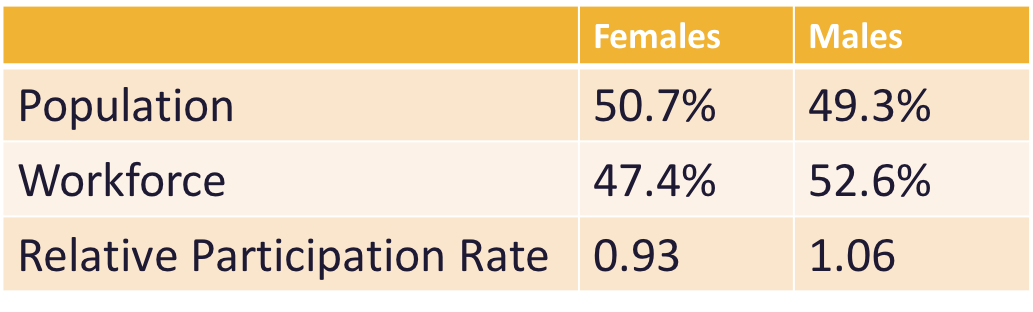

The makeup of the Canadian workforce has changed dramatically over the past 50 years. In the 1950s, more than 70 percent was composed of males.[7] Today’s workforce reflects the broad range of differences in the population—differences in gender, race, ethnicity, age, physical ability, religion, education, and lifestyle. As you can see below, more women have entered the workforce.[8]

Most companies today strive for diverse workforces. HR managers work hard to recruit, hire, develop, and retain a diverse workforce. In part, these efforts are motivated by legal concerns: discrimination in recruiting, hiring, advancement, and firing is illegal under federal law and is prosecuted by the Canadian Human Rights Tribunal. Companies that violate anti-discrimination laws are subject to severe financial penalties and also risk reputational damage.

Reasons for building a diverse workforce go well beyond mere compliance with legal standards. It even goes beyond commitment to ethical standards. It’s good business. People with diverse backgrounds bring fresh points of view that can be invaluable in generating ideas and solving problems. In addition, they can be the key to connecting with an ethnically diverse customer base. In short, capitalizing on the benefits of a diverse workforce means that employers should view differences as assets rather than liabilities.

- Price, A. (2004). Human Resource Management in a Business Context. Hampshire, U.K.: Cengage EMEA. Retrieved from: http://www.bestbooks.biz/learning/induction.html ↵

- Heathfield, S., M. (2015). “Top Ten Ways to Turn Off a New Employee.” Retrieved from: http://humanresources.about.com/library/weekly/aa022601a.htm ↵

- Jermyn, D., (2018). Diversity and inclusion give these firms a competitive advantage. Globe and Mail. Retrieved from: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/report-on-business/careers/top-employers/diversity-and-inclusion-give-these-firms-a-competitive-advantage/article38217315/ ↵

- Golfarb, Z. (2007). “Where Technocrats Play With Toys of Tomorrow.” The Washington Post. Retrieved from: http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/12/23/AR2007122301574.html ↵

- Locascio, B. (2004). “Working at Starbucks: More Than Just Pouring Coffee.” Tea and Coffee Trade Online. Retrieved from: http://www.teaandcoffee.net/0104/coffee.htm ↵

- Schultz, H. & Yang, D., J. (1997). Pour Your Heart into It: How Starbucks Built a Company One Cup at a Time. New York, NY: Hyperion. p. 250-251. ↵

- Usalcas, J. & Kinack, M. (2017). History of the Canadian Labour Force Survey, 1945 to 2016. Statistics Canada. Retrieved from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/75-005-m/75-005-m2016001-eng.pdf?st=VUjdeAww ↵

- Ibid. ↵