Operations Management in Manufacturing

Operations Management in Manufacturing

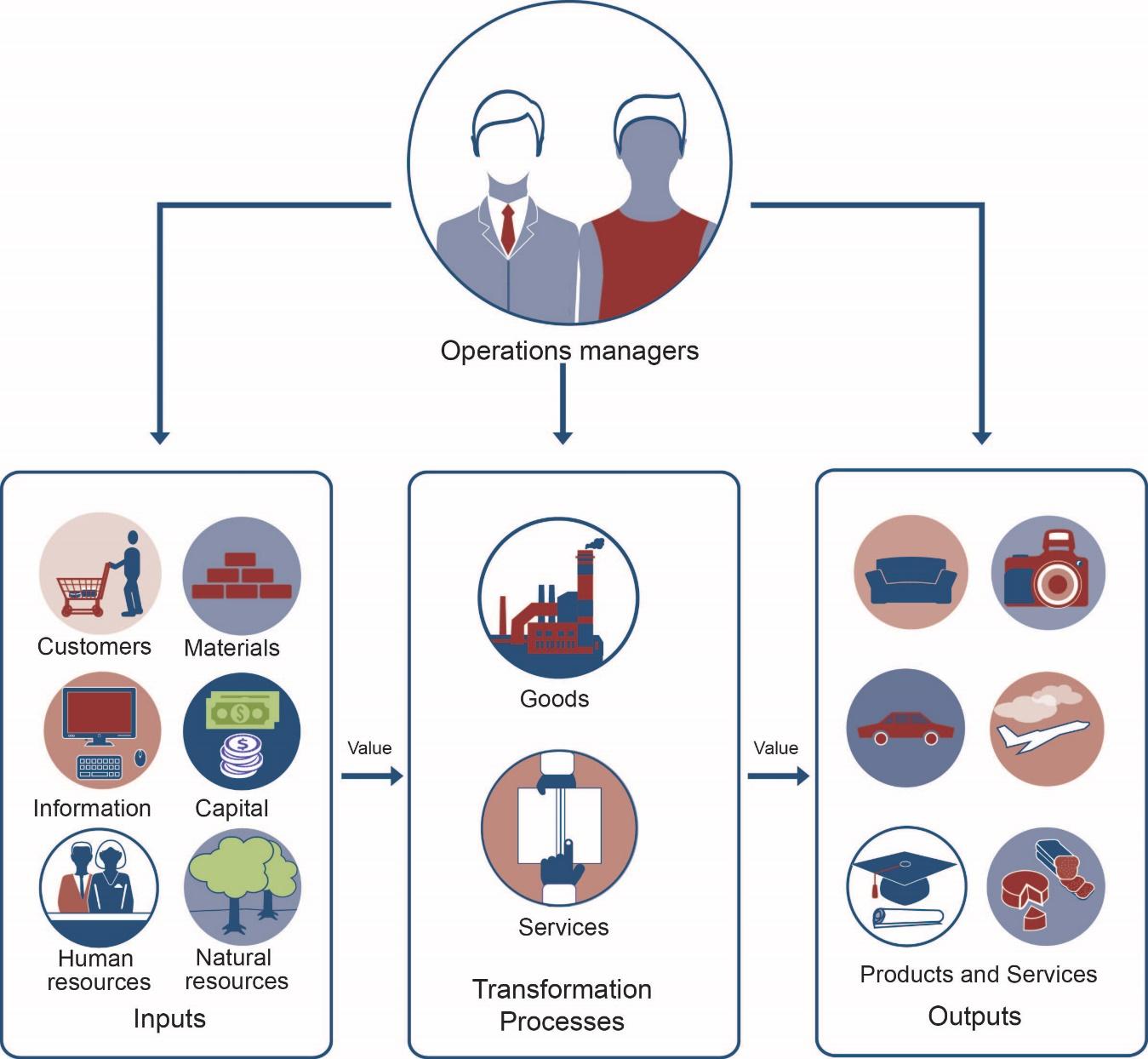

Like PowerSki, every organization—whether it produces goods or provides services— sees job #1 as furnishing customers with quality products. Thus, to compete with other organizations, a company must convert resources (materials, labour, money, information) into goods or services as efficiently as possible. The upper-level manager who directs this transformation process is called an operations manager. The job of operations management (OM) consists of all the activities involved in transforming a product idea into a finished product. Hence, because of the complexity of organizing all the activities in an organization it is more important than ever for Operations Management to ensure due diligence is utilized to structure operations. Due diligence is the important actions taken by directors or managers of an organization to ensure that all potential risks and errors are mitigated entirely. In addition, operations managers are involved in planning and controlling the systems that produce goods and services. In other words, operations managers manage the process that transforms inputs into outputs. The figure below illustrates these traditional functions of operations management.

Like PowerSki, all manufacturers set out to perform the same basic function: to transform resources into finished goods. To perform this function in today’s business environment, manufacturers must continually strive to improve operational efficiency. They must fine-tune their production processes to focus on quality, to hold down the costs of materials and labour, and to eliminate all costs that add no value to the finished product.

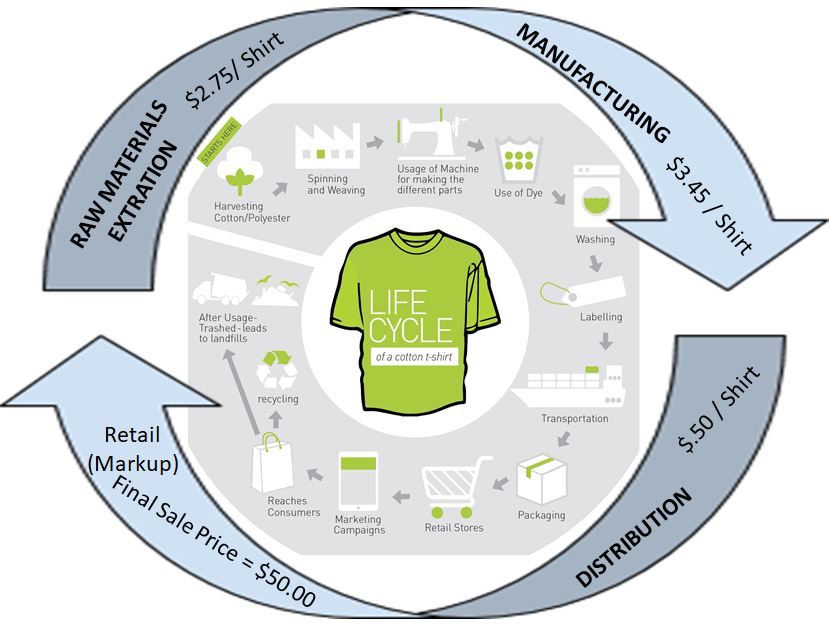

The Supply Chain identifies the process of transforming a product idea into a finished product, and how the process will convert raw materials into goods or services as efficiently as possible. The Value Chain identifies how value is added throughout the creation of the final good or service produced and how operational activities costs represent a proportion of the final sale price of the good or service.

Another job of operations managers is making the decisions involved in the effort to attain this operational organization and its goals. Their responsibilities can be grouped as follows:

- Production planning. During production planning, managers determine how goods will be produced, where production will take place, and how manufacturing facilities will be laid out.

- Production control. Once the production process is under way, managers must continually schedule and monitor the activities that make up that process. They must solicit and respond to feedback and make adjustments where needed. At this stage, they also oversee the purchasing of raw materials and the handling of inventories.

- Quality control. The operations manager is directly involved in efforts to ensure that goods are produced according to specifications and that quality standards are maintained.

Let’s take a closer look at each of these responsibilities.

Planning the Production Process

The decisions made in the planning stage have long-range implications and are crucial to a firm’s success. Before making decisions about the operations process, managers must consider the goals set by marketing managers. Does the company intend to be a low-cost producer and to compete on the basis of price? Or does it plan to focus on quality and go after the high end of the market? Many decisions involve trade-offs. For example, low cost doesn’t normally go hand in hand with high quality. All functions of the company must be aligned with the overall strategy to ensure success.

With these thoughts in mind, let’s look at the specific types of decisions that have to be made in the production planning process. We’ve divided these decisions into those dealing with production methods, site selection, facility layout, and components and materials management.

Production-Method Decisions

The first step in production planning is deciding which type of production process is best for making the goods that your company intends to manufacture. For example, this is depicted in figure above, illustrating the associated production process for a cotton shirt. In reaching this decision, you should answer such questions as:

- Am I making a one-of-a-kind good based solely on customer specifications, or am I producing high-volume standardized goods to be sold later?

- Do I offer customers the option of “customizing” an otherwise standardized good to meet their specific needs?

One way to appreciate the nature of this decision is by comparing three basic types of processes or methods: make-to-order, mass production, and mass customization. The task of the operations manager is to work with other managers, particularly marketers, to select the process that best serves the needs of the company’s customers.

Make-to-Order

At one time, most consumer goods, such as furniture and clothing, were made by individuals practising various crafts. By their very nature, products were customized to meet the needs of the buyers who ordered them. This process, which is called a make-to-order strategy, is still commonly used by such businesses as print or sign shops that produce low-volume, high-variety goods according to customer specifications. This level of customization often results in a longer production and delivery cycle than other approaches.

Mass Production

By the early twentieth century, a new concept of producing goods had been introduced: mass production (or make-to-stock strategy), the practice of producing high volumes of identical goods at a cost low enough to price them for large numbers of customers. Goods are made in anticipation of future demand (based on forecasts) and kept in inventory for later sale. This approach is particularly appropriate for standardized goods ranging from processed foods to electronic appliances. It generally results in shorter cycle times than a make-to-order process. This type of production also takes advantage of economies of scale, which refers to the reduced costs per unit that is realized from increased total number of units produced.

Mass Customization

There is at least one big disadvantage to mass production: customers, as one old advertising slogan put it, can’t “have it their way.” They have to accept standardized products as they come off assembly lines. Increasingly, however, customers are looking for products that are designed to accommodate individual tastes or needs but can still be bought at reasonable prices. To meet the demands of these consumers, many companies have turned to an approach called mass customization, which combines the advantages of customized products with those of mass production.

This approach requires that a company interact with the customer to find out exactly what the customer wants and then manufacture the good, using efficient production methods to hold down costs. One efficient method is to mass-produce a product up to a certain cut-off point and then to customize it to satisfy different customers.

One of the best-known mass customizers is Nike, which has achieved success by allowing customers to configure their own athletic shoes, apparel, and equipment through NikeiD program. The Web has a lot to do with the growth of mass customization. Levi’s, for instance, lets customers find a pair of perfect fitting jeans by going through an online fitting process. Oakley offers customized sunglasses, goggles, watches, and backpacks, while Mars, Inc. can make M&M’s in any color the customer wants (say, school colours) as well as add text and even pictures to the candy.

Naturally, mass customization doesn’t work for all types of goods. Most people don’t care about customized detergents or paper products. And while many of us like the idea of customized clothes, footwear, or sunglasses, we often aren’t willing to pay the higher prices they command.

Facilities Decisions

After selecting the best production process, operations managers must then decide where the goods will be manufactured, how large the manufacturing facilities will be, and how those facilities will be laid out.

Site Selection

In site selection (choosing a location for the business), managers must consider several factors:

- To minimize shipping costs, managers often want to locate plants close to suppliers, customers, or both.

- They generally want to locate in areas with ample numbers of skilled workers.

- They naturally prefer locations where they and their families will enjoy living.

- They want locations where costs for resources and other expenses—land, labour, construction, utilities, and taxes—are low.

- They look for locations with a favourable business climate—one in which, for example, local governments might offer financial incentives (such as tax breaks) to entice them to do business in their locales. For example, an enterprise zone is an area in which incentives are used to attract investments from private companies.

Managers rarely find locations that meet all these criteria. As a rule, they identify the more important criteria and aim at satisfying them. In deciding to locate in San Clemente, California, for instance, PowerSki was able to satisfy three important criteria: (1) proximity to the firm’s suppliers, (2) availability of skilled engineers and technicians, and (3) favourable living conditions. These factors were more important than operating in a low-cost region or getting financial incentives from local government. Because PowerSki distributes its products throughout the world, proximity to customers was also unimportant.

Capacity Planning

Now that you know where you’re going to locate, you have to decide on the quantity of products that you’ll produce. You begin by forecasting demand for your product, which isn’t easy. To estimate the number of units that you’re likely to sell over a given period, you have to understand the industry that you’re in and estimate your likely share of the market by reviewing industry data and conducting other forms of research.

Once you’ve forecasted the demand for your product, you can calculate the capacity requirements of your production facility—the maximum number of goods that it can produce over a given time under normal working conditions. In turn, having calculated your capacity requirements, you’re ready to determine how much investment in plant and equipment you’ll have to make, as well as the number of labour hours required for the plant to produce at capacity and meet demand.

Like forecasting, capacity planning is difficult. Unfortunately, failing to balance capacity and projected demand can be seriously detrimental to your bottom line. If you set capacity too low (and so produce less than you should), you won’t be able to meet demand, and you’ll lose sales and customers. If you set capacity too high (and turn out more units than you should), you’ll waste resources and inflate operating costs. Therefore continuous review, the process of routinely reviewing the organization’s processes to determine where improvements can be made to increase organizational efficiency, is very important in the capacity planning process to avoid producing too much or too little.