The Globalization of Business

Do you wear Nike shoes or Timberland boots? Listen to Beyoncé, Pitbull, Twenty One Pilots, or The Neighborhood on Spotify? If you answered yes to either of these questions, you’re a global business customer. Both Nike and Timberland manufacture most of their products overseas. Spotify is a Swedish enterprise.

Take an imaginary walk down Orchard Road, the most fashionable shopping area in Singapore. You’ll pass department stores such as Tokyo-based Takashimaya and London’s very British Marks & Spencer, both filled with such well-known international labels as Ralph Lauren Polo, Burberry, and Chanel. If you need a break, you can also stop for a latte at Seattle-based Starbucks.

When you’re in the Chinese capital of Beijing, don’t miss Tiananmen Square. Parked in front of the Great Hall of the People, the seat of Chinese government, are fleets of black Buicks, cars made by General Motors in Flint, Michigan. If you’re adventurous enough to find yourself in Faisalabad, a medium-size city in Pakistan, you’ll see Hamdard University, located in a refurbished hotel. Step inside its computer labs, and the sensation of being in a faraway place will likely disappear: on the computer screens, you’ll recognize the familiar Microsoft flag—the same one emblazoned on screens in Microsoft’s hometown of Seattle and just about everywhere else on the planet.

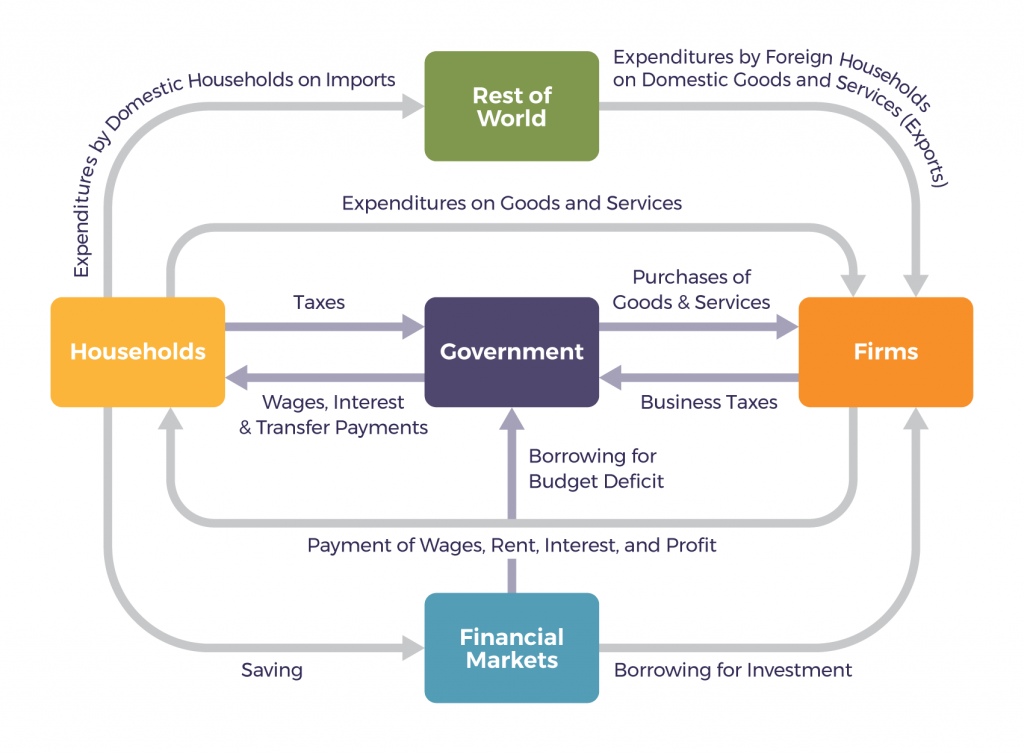

The globalization of business is bound to affect you. Not only will you buy products manufactured overseas, but it’s likely that you’ll meet and work with individuals from various countries and cultures as customers, suppliers, colleagues, employees, or employers. The bottom line is that the globalization of world commerce has an impact on all of us ~ evidenced in the figure below, The Expanded Circular Flow Model. Therefore, it makes sense to learn more about how globalization works.

Never before has business spanned the globe the way it does today and will continue to do in the future. But why is international business important? Why do companies and nations engage in international trade? What strategies do they employ in the global marketplace? How do governments and international agencies promote and regulate international trade? These questions and others will be addressed in this chapter. Let’s start by looking at the more specific reasons why companies and nations engage in international trade.

Why Do Nations Trade?

Why does Canada import automobiles, steel, digital phones, and apparel from other countries? Why don’t we just make them ourselves? Why do other countries buy wheat, chemicals, machinery, and lumber products from us? Because no national economy produces all the goods and services that its people need. Countries are importers when they buy goods and services from other countries; when they sell products to other nations, they’re exporters. (We’ll discuss importing and exporting in greater detail later in the chapter.) The monetary value of international trade is enormous. In 2016, the total value of worldwide trade in merchandise and commercial services was $20.208 trillion. [1]

Absolute and Comparative Advantage

To understand why certain countries import or export certain products, you need to realize that every country (or region) can’t produce the same products. The cost of labour, the availability of natural resources, and the level of know-how vary greatly around the world. Most economists use the concepts of absolute advantage and comparative advantage to explain why countries import some products and export others.

Absolute Advantage

A nation has an absolute advantage if (1) it’s the only source of a particular product or (2) it can make more of a product using fewer resources than other countries. Because of climate and soil conditions, for example, France had an absolute advantage in wine making until its dominance of worldwide wine production was challenged by the growing wine industries in Italy, Spain, the United States, and more recently Canada. Unless an absolute advantage is based on some limited natural resource, it seldom lasts. That’s why there are few, if any, examples of absolute advantage in the world today.

Comparative Advantage

How can we predict, for any given country, which products will be made and sold at home, which will be imported, and which will be exported? This question can be answered by looking at the concept of comparative advantage, which exists when a country can produce a product at a lower opportunity cost compared to another nation. But what’s an opportunity cost?

Opportunity costs

Since resources are limited, every time you make a choice about how to use them, you are also choosing to forego other options. Economists use the term opportunity cost to indicate what must be given up to obtain something that is desired. A fundamental principle of economics is that every choice has an opportunity cost.

- If you sleep through your economics class (not recommended, by the way), the opportunity cost is the learning you miss.

- If you spend your income on video games, you cannot spend it on movies.

- If you choose to marry one person, you give up the opportunity to marry anyone else.

In short, opportunity cost is all around us.

The idea behind opportunity cost is that the cost of one item is the lost opportunity to do or consume something else; in short, opportunity cost is the value of the next best alternative.

Since people and businesses must choose, they inevitably face trade-offs in which they have to give up things they desire to get other things they desire more.

Opportunity Cost and Individual Decisions

In some cases, recognizing the opportunity cost can alter personal behaviour. Imagine, for example, that you spend $10 on lunch every day at work. You may know perfectly well that bringing a lunch from home would cost only $3 a day, so the opportunity cost of buying lunch at the restaurant is $7 each day (that is, the $10 that buying lunch costs minus the $3 your lunch from home would cost). Ten dollars each day does not seem to be that much. However, if you project what that adds up to in a year—250 workdays a year × $10 per day equals $2 500—it is the cost, perhaps, of a decent vacation. If the opportunity cost were described as “a nice vacation” instead of “$10 a day” you might make different choices.

Opportunity Cost and Societal Decisions

Opportunity cost also comes into play with societal decisions. Universal health care including drugs would be nice, but the opportunity cost of such a decision would be less housing, environmental protection, or national defense. These trade-offs also arise with government policies. For example, after the terrorist plane hijackings on September 11, 2001, many proposals, such as the following, were made to improve air travel safety:

- Federal governments could provide armed “sky marshals” who would travel inconspicuously with the rest of the passengers. The cost of having a sky marshal on every flight would be roughly $3 billion per year.

- Retrofitting all planes with reinforced cockpit doors to make it harder for terrorists to take over the plane would have a price tag of $450 million for the US alone.

- Buying more sophisticated security equipment for airports, like three-dimensional baggage scanners and cameras linked to face-recognition software, would cost another $2 billion in the US.

Lost time can be a significant component of opportunity cost.

However, the single biggest cost of greater airline security does not involve money. It is the opportunity cost of additional waiting time at the airport. According to the United States Department of Transportation, more than 800 million passengers took plane trips in the United States in 2012. Since the 9/11 hijackings, security screening has become more intensive, and consequently, the procedure takes longer than in the past. Say that, on average, each air passenger spends an extra 30 minutes in the airport per trip. Economists commonly place a value on time to convert an opportunity cost in time into a monetary figure. Because many air travelers are relatively highly paid business people, conservative estimates set the average “price of time” for air travelers at $20 per hour. Accordingly, the opportunity cost of delays in airports could be as much as 800 million (passengers) × 0.5 hours × $20/hour—or, $8 billion per year. Clearly, the opportunity costs of waiting time can be just as substantial as costs involving direct spending.

How Do We Measure Trade Between Nations?

To evaluate the nature and consequences of its international trade, a nation looks at two key indicators. We determine a country’s balance of trade by subtracting the value of its imports from the value of its exports. If a country sells more products than it buys, it has a favourable balance, called a trade surplus. If it buys more than it sells, it has an unfavourable balance or a trade deficit.

For many years, Canada has had a trade deficit: we buy far more goods from the rest of the world than we sell overseas. This fact shouldn’t be surprising. With high-income levels, we not only consume a sizable portion of our own domestically produced goods but enthusiastically buy imported goods. Other countries, such as China and Taiwan, which manufacture high volumes for export, have large trade surpluses because they sell far more goods overseas than they buy.

Managing the National Credit Card

Are trade deficits a bad thing? Not necessarily. They can be positive if a country’s economy is strong enough both to keep growing and to generate the jobs and incomes that permit its citizens to buy the best the world has to offer. That was certainly the case in Canada in the 1990s and early 2000s. Some experts, however, are alarmed by trade deficits. Investment guru Warren Buffet, for example, cautions that no country can continuously sustain large and burgeoning trade deficits. Why not? Because creditor nations will eventually stop taking IOUs from debtor nations, and when that happens, the national spending spree will have to cease. “A nation’s credit card,” he warns, “charges truly breathtaking amounts. But that card’s credit line is not limitless”. [2]

By the same token, trade surpluses aren’t necessarily good for a nation’s consumers. Japan’s export-fueled economy produced high economic growth in the 1970s and 1980s. But most domestically-made consumer goods were priced at artificially high levels inside Japan itself—so high, in fact, that many Japanese traveled overseas to buy the electronics and other high-quality goods on which Japanese trade was dependent.

CD players and televisions were significantly cheaper in Honolulu or Los Angeles than in Tokyo. How did this situation come about? Though Japan manufactures a variety of goods, many of them are made for export. To secure shares in international markets, Japan prices its exported goods competitively. Inside Japan, because competition is limited, producers can put artificially high prices on Japanese-made goods. Due to a number of factors (high demand for a limited supply of imported goods, high shipping and distribution costs, and other costs incurred by importers in a nation that tends to protect its own industries), imported goods are also expensive.[3]

Balance of Payments

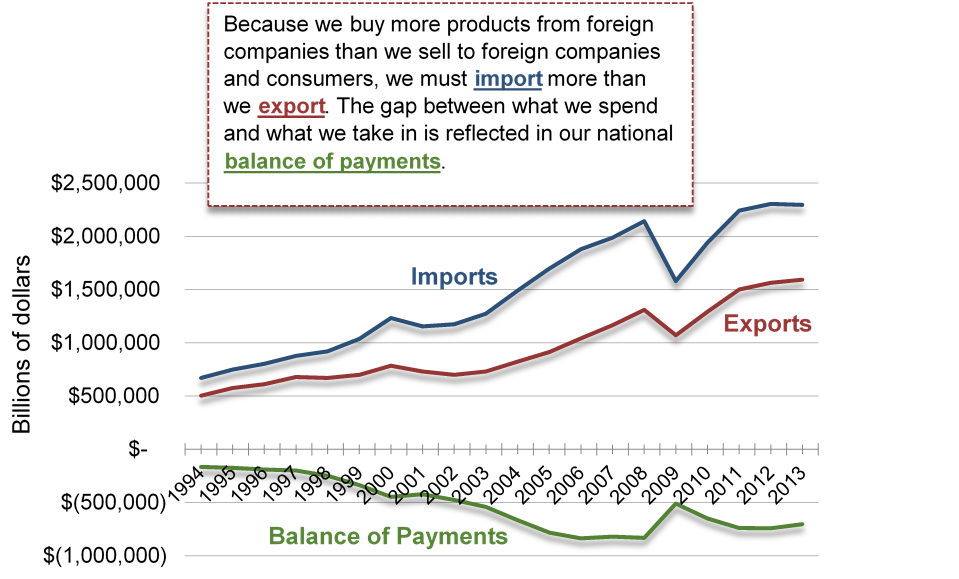

The second key measure of the effectiveness of international trade is balance of payments: the difference, over a period of time, between the total flow of money coming into a country and the total flow of money going out. As in its balance of trade, the biggest factor in a country’s balance of payments is the money that flows as a result of imports and exports. But balance of payments includes other cash inflows and outflows, such as cash received from or paid for foreign investment, loans, tourism, military expenditures, and foreign aid. For example, if a Canadian company buys some real estate in a foreign country, that investment counts in the Canadian balance of payments, but not in its balance of trade, which measures only import and export transactions. In the long run, having an unfavourable balance of payments can negatively affect the stability of a country’s currency. Canada has experienced unfavourable balances of payments since the turn of the century which has forced the government to cover its debt by borrowing from other countries. [4] The graph below provides an example of the balance of payments over time.

- World Trade Organization. (2017). Merchandise trade and trade in commercial services. Retrieved from: https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/statis_e/wts2017_e/WTO_Chapter_04_e.pdf ↵

- Buffet, W. E., & Loomis, C. (2003, November 10). America’s Growing Trade Deficit Is Selling The Nation Out From Under Us. Here’s A Way To Fix The Problem–And We Need To Do It Now. Fortune. Retrieved from: http://archive.fortune.com/magazines/fortune/fortune_archive/2003/11/10/352872/index.htm ↵

- Anonymous. (2003). Why Are Prices in Japan So Damn High? The Japan FAQ.com. Retrieved from: http://www.thejapanfaq.com/FAQ-Prices.html ↵

- Trading Economics. (n.d.). Canada current account. Retrieved from: https://tradingeconomics.com/canada/current-account ↵