Identifying Ethical Issues and Dilemmas

Ethical issues are the difficult social questions that involve some level of controversy over what is the right thing to do. Environmental protection is an example of a commonly discussed ethical issue, because there can be trade-offs between environmental and economic factors.

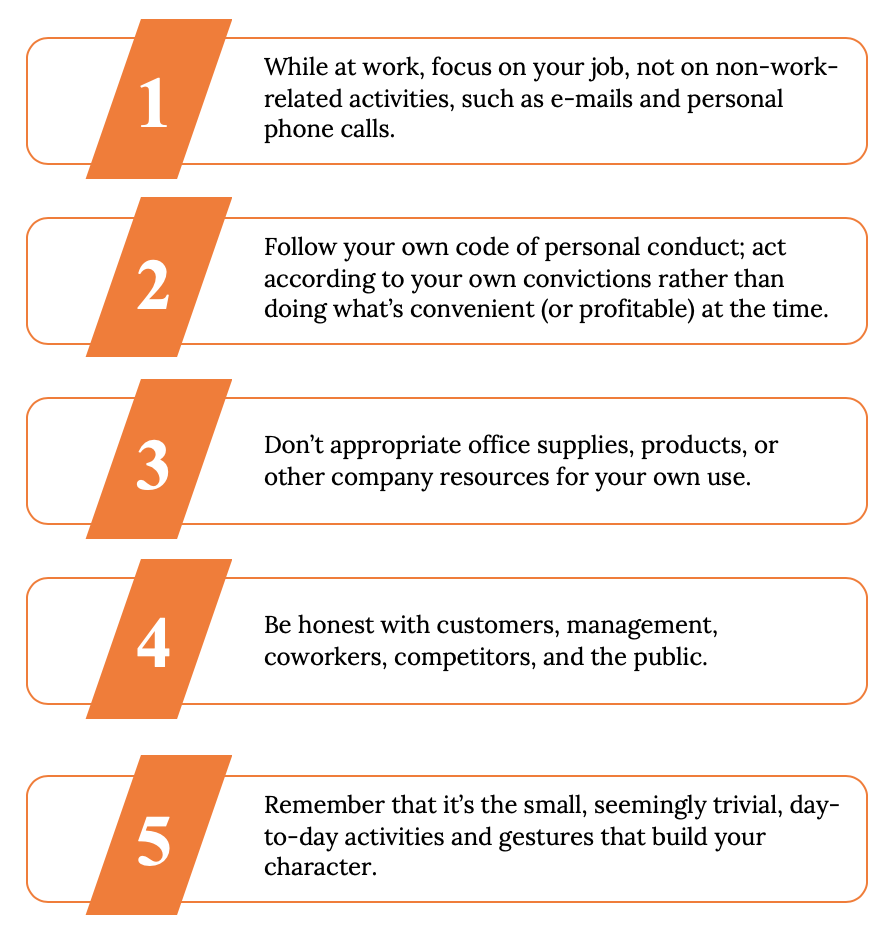

- Follow your own code of personal conduct; act according to your own convictions rather than doing what’s convenient (or profitable) at the time.

- While at work, focus on your job, not on non-work related activities, such as emails and personal phone calls.

- Don’t appropriate office supplies or products or other company resources for your own use.

- Be honest with customer, management, coworkers, competitors, and the public.

- Remember that it’s the small seemingly trivial, day-to-day activities and gestures that build your character.

Make no mistake about it: when you enter the business world, you’ll find yourself in situations in which you’ll have to choose the appropriate behaviour. How, for example, would you answer questions like the following?

- Is it OK to accept a pair of sports tickets from a supplier?

- Can I buy office supplies from my brother-in-law?

- Is it appropriate to donate company funds to a local charity?

- If I find out that a friend is about to be fired, can I warn her?

Obviously, the types of situations are numerous and varied. Fortunately, we can break them down into a few basic categories: issues of honesty and integrity, conflicts of interest and loyalty, bribes versus gifts, and whistle-blowing. Let’s look a little more closely at each of these categories.

Issues of Honesty and Integrity

Master investor Warren Buffet once told a group of business students the following: “I cannot tell you that honesty is the best policy. I can’t tell you that if you behave with perfect honesty and integrity somebody somewhere won’t behave the other way and make more money. But honesty is a good policy. You’ll do fine, you’ll sleep well at night and you’ll feel good about the example you are setting for your coworkers and the other people who care about you”. [1]

If you work for a company that settles for its employees’ merely obeying the law and following a few internal regulations, you might think about moving on. If you’re being asked to deceive customers about the quality or value of your product, you’re in an ethically unhealthy environment.

Think about this story:

“A chef put two frogs in a pot of warm soup water. The first frog smelled the onions, recognized the danger, and immediately jumped out. The second frog hesitated: The water felt good, and he decided to stay and relax for a minute. After all, he could always jump out when things got too hot (so to speak). As the water got hotter, however, the frog adapted to it, hardly noticing the change. Before long, of course, he was the main ingredient in frog-leg soup.” [2]

So, what’s the moral of the story? Don’t sit around in an ethically toxic environment and lose your integrity a little at a time; get out before the water gets too hot and your options have evaporated. We’ve summed up some rules of thumb you might apply to guide you ethical decision making:

Conflicts of Interest

Conflicts of interest occur when individuals must choose between taking actions that promote their personal interests over the interests of others or taking actions that don’t. A conflict can exist, for example, when an employee’s own interests interfere with, or have the potential to interfere with, the best interests of the company’s stakeholders (management, customers, and owners). Let’s say that you work for a company with a contract to cater events at your college and that your uncle owns a local bakery. Obviously, this situation could create a conflict of interest (or at least give the appearance of one—which is a problem in itself). When you’re called on to furnish desserts for a luncheon, you might be tempted to send some business your uncle’s way even if it’s not in the best interest of your employer. What should you do? You should disclose the connection to your boss, who can then arrange things so that your personal interests don’t conflict with the company’s.

The same principle holds that an employee shouldn’t use private information about an employer for personal financial benefit. Say that you learn from a coworker at your pharmaceutical company that one of its most profitable drugs will be pulled off the market because of dangerous side effects. The recall will severely hurt the company’s financial performance and cause its stock price to plummet. Before the news becomes public, you sell all the stock you own in the company. What you’ve done is called insider trading – acting on information that is not available to the general public, either by trading on it or providing it to others who trade on it. Insider trading is illegal, and you could go to jail for it.

Conflicts of Loyalty

You may one day find yourself in a bind between being loyal either to your employer or to a friend or family member. Perhaps you just learned that a coworker, a friend of yours, is about to be downsized out of his job. You also happen to know that he and his wife are getting ready to make a deposit on a house near the company headquarters. From a work standpoint, you know that you shouldn’t divulge the information. From a friendship standpoint, though, you feel it’s your duty to tell your friend. Wouldn’t he tell you if the situation were reversed? So what do you do? As tempting as it is to be loyal to your friend, you shouldn’t tell. As an employee, your primary responsibility is to your employer. You might be able to soften your dilemma by convincing a manager with the appropriate authority to tell your friend the bad news before he puts down his deposit.

Bribes Versus Gifts

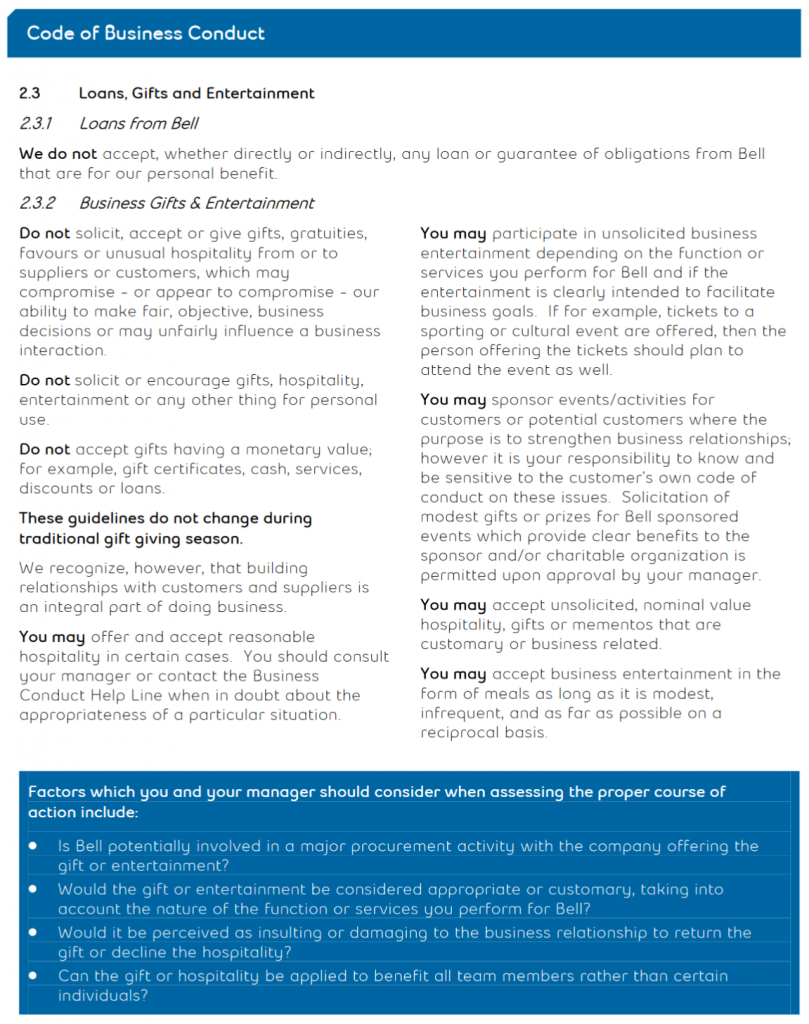

It’s not uncommon in business to give and receive small gifts of appreciation, but when is a gift unacceptable? When is it really a bribe?

There’s often a fine line between a gift and a bribe. The following information may help in drawing it, because it raises key issues in determining how a gesture should be interpreted: the cost of the item, the timing of the gift, the type of gift, and the connection between the giver and the receiver. If you’re on the receiving end, it’s a good idea to refuse any item that’s overly generous or given for the purpose of influencing a decision. Because accepting even small gifts may violate company rules, always check on company policy.

Read through Bell Canada’s Code of Business Conduct detailing its recommendations for gifts.

Whistleblowing

Whistleblowing was defined in 1972 by Ralph Nader as “an act of a man or a woman who, believing in the public interest overrides the interest of the organization he serves, publicly blows the whistle if the organization is involved in corrupt, illegal, fraudulent or harmful activity”.

While there are increasing incentives from governments and regulators for whistleblowers to go public about corporate misconduct, protections for whistleblowers are still very limited. Few Canadian laws pertain directly to whistleblowing and therefore whistleblowers are mostly unprotected by statute.

There is, however, a patchwork of protection provisions for whistleblowers under the Canadian Criminal Code, Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act (PSDPA), the Public Service of Ontario Act, 2006 as well as the Securities Act.

Section 425.1 of the Criminal Code, for example, states that employers may not threaten or take disciplinary action against, demote or terminate an employee in order to deter her/him from reporting information regarding an offence s/he believes has or is being committed by her/his employer to the relevant law enforcement authorities.

An employer cannot threaten an employee with negative repercussions to deter them from contacting law enforcement with information about the employer’s offence. Punishment for employers who make such threats or reprisals can include up to five years imprisonment and/or fines.

In early 2018, a Canadian whistleblower received worldwide recognition for disclosing the amount and kinds of data harvested by Cambridge Analytica through personal Facebook accounts.

Examples

Read about other prominent Canadian whistleblowers on the Centre for Free Expression website.[3]

- Gostick, A., & Telford D. (2003). The Integrity Advantage. Salt Lake City: Gibbs Smith. ↵

- Gostick, A., & Telford D. (2003). The Integrity Advantage. Salt Lake City: Gibbs Smith. ↵

- Centre for Free Expression, & Hutton, D. (2016, December 2). Prominent Canadian Whistleblowers. Centre for Free Expression. https://cfe.torontomu.ca/lists/prominent-canadian-whistleblowers ↵