3.2 Opioids (an overview)

Opioids are a category of psychoactive substance that refer to substances derived from opium, opium derivatives, and their semi-synthetic substitutes. Examples you may be aware of include heroin, morphine, methadone and fentanyl.

What is their origin?

The poppy Papaver somniferum is the source of all-natural opioids, whereas synthetic opioids are made entirely in a lab and include meperidine, fentanyl, and methadone Semi-synthetic opioids are synthesized from naturally occurring opium products, such as morphine and codeine, and include heroin, oxycodone, hydrocodone, and hydromorphone.

What do they look like?

Opioids come in various forms, including tablets, capsules, skin patches, powder, chunks in varying colors (from white to shades of brown and black), liquid form for oral use and injection, syrups, suppositories, and lollipops. Opioids can be swallowed, smoked, sniffed, injected or used transdermally.

What is their effect on the brain?

Besides their medical use, opioids produce a general sense of well-being by reducing tension, anxiety, and aggression. These effects are helpful in a therapeutic setting but contribute to misuse. Opioid use comes with a variety of unwanted effects, including drowsiness, inability to concentrate, and apathy.

What is their effect on the body?

Opioids are prescribed to treat pain, suppress a cough, cure diarrhea, and put people to sleep. Effects depend heavily on the dose, how it is taken, and previous exposure to the substance. Negative effects include slowed physical activity, constriction of the pupils, flushing of the face and neck, constipation, nausea, vomiting, and slowed breathing. As the dose is increased, both the pain relief and the harmful effects become more pronounced. A single dose can be lethal to an inexperienced person or someone who has been in recovery.

Dependence

Continuing use of opioids can create both physical and psychological dependence. Physical dependence is a consequence of chronic opioid use, and withdrawal takes place when the use is discontinued. The intensity and character of the physical symptoms experienced during withdrawal are directly related to the substance, the daily amount used, the interval between doses, the duration of use, and the health and personality of the person using the opiate. These symptoms usually appear shortly before the time of the next scheduled dose, increasing dependence.

Early withdrawal symptoms often include watery eyes, runny nose, yawning, and sweating. As the withdrawal worsens, symptoms can include: Restlessness, irritability, loss of appetite, nausea, tremors, drug craving, severe depression, vomiting, increased heart rate, and blood pressure, and chills alternating with flushing and excessive sweating. Without intervention, the withdrawal usually runs its course, and most physical symptoms disappear within days or weeks, depending on the particular substance. Withdrawal is extremely uncomfortable, and is one reason why people continue to use opioids. Long after the physical need for the substance has passed, people may continue to think and talk about using and feel overwhelmed coping with daily activities. Relapse is common if there are no changes to the physical, biological, social, or other factors that contributed to the use/abuse of the opioid.

Overdose

Overdoses are common and can be fatal with opiate use. Physical signs of opioid overdose include:

- constricted (pinpoint) pupils

- cold clammy skin, confusion

- convulsions

- extreme drowsiness

- slowed breathing

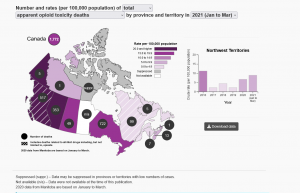

Opioid overdose is a crisis in Canada and tens of thousands of lives have been needlessly lost; between 2016 and September 2021 over 22,000 people died, that is twenty people per day who lost their lives to an opiate overdose.[1] Review the map below to see the impact of opiate overdose in each province and territory in Canada.

Overdose from opiates is not a phenomenon that impacts any group more than others, the deaths cut across social and economic lines. There are groups that are considered more vulnerable, for example people who are homeless are at higher risk of death from overdose.[2] Indigenous people are significantly over-represented in the loss of lives in Canada. Recent data from Alberta and British Columbia, the provinces most heavily impacted by the crisis, indicates that First Nations people are five times more likely to experience an overdose and three times more likely to die from overdose than non-First Nations people.[3] While men aged 30 to 39 make up the biggest group of deaths across the country, women are dying at a similar rate in the Prairies and eastern provinces.[4]

- Why are marginalized groups, including Indigenous communities at higher risk for overdose?

- Where would you go for information about opioid overdose in Nova Scotia?

Preventing Overdose

Naloxone kits have been available to the community since 2017 in Nova Scotia. Naloxone is used to treat an opioid overdose, it is a temporary opiate antagonist (a substance which blocks or reverses the effects of opioids, including extreme drowsiness, slowed breathing, or loss of consciousness). This temporarily reverses an overdose; however medical intervention is still required. Naloxone is NOT permanent. NS health recommends that if a person who has overdosed is not taken to a hospital, the overdose victim can fall back into the overdose within 30 minutes; therefore Naloxone should not be considered as step 1, in a multi-step process for addressing an opiate overdose. Please review the 5 steps by the NS Take Home Naloxone Program.

Naloxone only works for opioids, if someone has overdosed on a stimulant or depressant, Naloxone will not work, but it will also not cause harm. If an overdose involves multiple substances, including opioids, Naloxone helps by temporarily blocking or removing the opioid.[5] Watch the following video from Nova Scotia Health promoting the importance of accessing naloxone kits.[6]

In Nova Scotia, Naloxone kits are free and available to adults over the age of 18. Below you will find more information on the NS Take Home Naloxone Program.

As you are learning, opiates are having an impact on all communities in Canada. As Social Service workers, you may consider accessing a naloxone kit. You can save a life.

Chapter Credit

Adapted from the Unit 3.2 in Drugs, Health & Behavior by Jacqueline Schwab. CC BY-NC-SA. Updated with Canadian Content.

Image Credits

- Narcotics, Drugs of Abuse from: U.S. Department of Justice Drug Enforcement Administration. (2017). Drugs of abuse (p. 38). https://www.dea.gov/sites/default/files/2018-06/drug_of_abuse.pdf

- Special Advisory Committee on the Epidemic of Opioid Overdoses. (2022, March). Opioid- and Stimulant-related Harms in Canada. Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada. https://health-infobase.canada.ca/substance-related-harms/opioids-stimulants

- NS Take Home Naloxone Program. (2021). Program Overview [Infographic]. http://www.nsnaloxone.com/uploads/1/1/2/0/112043611/thn_orig.png

- Government of Canada. (2021). Opioid- and stimulant-related harms in Canada. https://health-infobase.canada.ca/substance-related-harms/opioids-stimulants ↵

- Bauer, L. K., Brody, J. K., León, C., & Baggett, T. P. (2016). Characteristics of homeless adults who died of drug overdose: A retrospective record review. Journal of health care for the poor and underserved, 27(2), 846–859. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2016.0075 ↵

- Jongbloed, K., Pearce, M., Pooyak, S., Zamar, D., Thomas, V., Demerais, L., Christian, W., Henderson, E., Sharma, R., Blair, A., Yoshida, E., Schechter, M.,& Spittal, P. (2017). The cedar project: mortality among young Indigenous people who use drugs in British Columbia. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 189(44), 1352-1359. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.160778 ↵

- CATIE. (2020). The positive side magazine. https://www.catie.ca/en/positiveside/spring-2020/lessons-not-learned ↵

- NS Take Home Naloxone Program. (2021b). Learn more. http://www.nsnaloxone.com/learn-more.html ↵

- Nova Scotia Health. (2018). Naloxone: Who is your kit for? [Video]. Vimeo. https://vimeo.com/300496867 ↵