7.1 Overview

When you purchase a coffee, have you ever wondered why it is accessible to anyone, though we know caffeine has a biological impact on brain and body? Have you ever thought about why tobacco products, marijuana, alcohol, or even your prescription medicines are less accessible, and asked who made these decisions? This module will start with an exploration of substances and laws.

7.1A Activities

-

- Research laws on substances in Canada.

- What laws make sense to you? Which do you think need work?

- Who do you think the laws on substances affect?

There is little disagreement that there is an international “war on drugs;” and yet the war on drugs has resulted in the criminalization, stigmatization and increased health harms of people who use substances.[1] A growing number of people in the political world agree; “the global war on drugs has failed, with devastating consequences for individuals and societies around the world…fundamental reforms in national and global drug control policies are urgently needed”.[2] While the United Nations General Assembly Special Session (UNGASS) and the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) released a joint commitment in 2016 to address substance use, it still focused on reduction of access. There was, however, a recognition that substance use laws must shift to a more human rights and health promotion approach.[3]

Given this backdrop, the question of whether our current substance use policies in Canada make sense must be asked. Experts in this field in Canada, from Gabor Mate to Donald MacPherson suggest the best approach our society could take is to decriminalize all substances and expand prevention, treatment, and harm reduction approaches that support various theories of use, ridding policy of moral models.[4]

Canada would not be the first country to decriminalize substances; “Czechia, the Netherlands, Portugal and Switzerland are among a handful of countries that have decriminalized drug use and possession for personal use and that have also invested in harm reduction programmes”.[5] How has decriminalization impacted these countries?

The Netherlands*

The Netherlands decriminalized substances in 1976.[6] The strategy taken by the Netherlands was a four-pillar approach focusing on (i) preventing substance use and treating and rehabilitating people who use substances; (ii) reducing harm to users; (iii) diminishing public nuisance caused by people who use substances and; (iv) combatting the production and trafficking of drugs.[7] Under the Netherlands’ policy, people who use substances are not normally arrested for possession (excluding cocaine and heroin), but they must receive treatment if they are arrested for another reason.[8] Traffickers are not arrested for selling small amounts of substances, but they may be arrested for selling them in large quantities.

The impacts of these changes resulted in marijuana, cocaine and heroin use dropping in the immediate years after it was decriminalized. For example, data from the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction[9] estimated approximately 1.4% of people participate in high-risk cannabis use (daily use). In Canada, 7.9% of Canadians aged 15 and older report high risk cannabis use.[10] In the Netherlands, there has been a decreasing trend in lifetime cannabis use among school-age children over the period 1999-2015.[11] Data from the 2017 Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) study showed a decrease in lifetime prevalence of cannabis use among students aged 12-16 years from 16.5 % in 2003 to 9.2 % in 2017.[12] In Canada, however, over 19% of those ages 15-17 used cannabis and nearly 20.0% of Canadians between the ages of 15-64 reported having used cannabis in the past three months.[13] In the Netherlands, while there has been an increase in the number of people who use opioids as experienced throughout Europe and North America, “no increase has been described in the number of opioid-related deaths”.[14] In 2017 in Canada according to the Canadian Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Survey, the prevalence of opioid use was 11.8%,[15] and the number of opioid related deaths increased by 2% from 2016-2020 with 24,626 apparent opioid toxicity deaths.[16] By offering a variety of supports to people who use substances, the Netherlands is saving lives.

Portugal

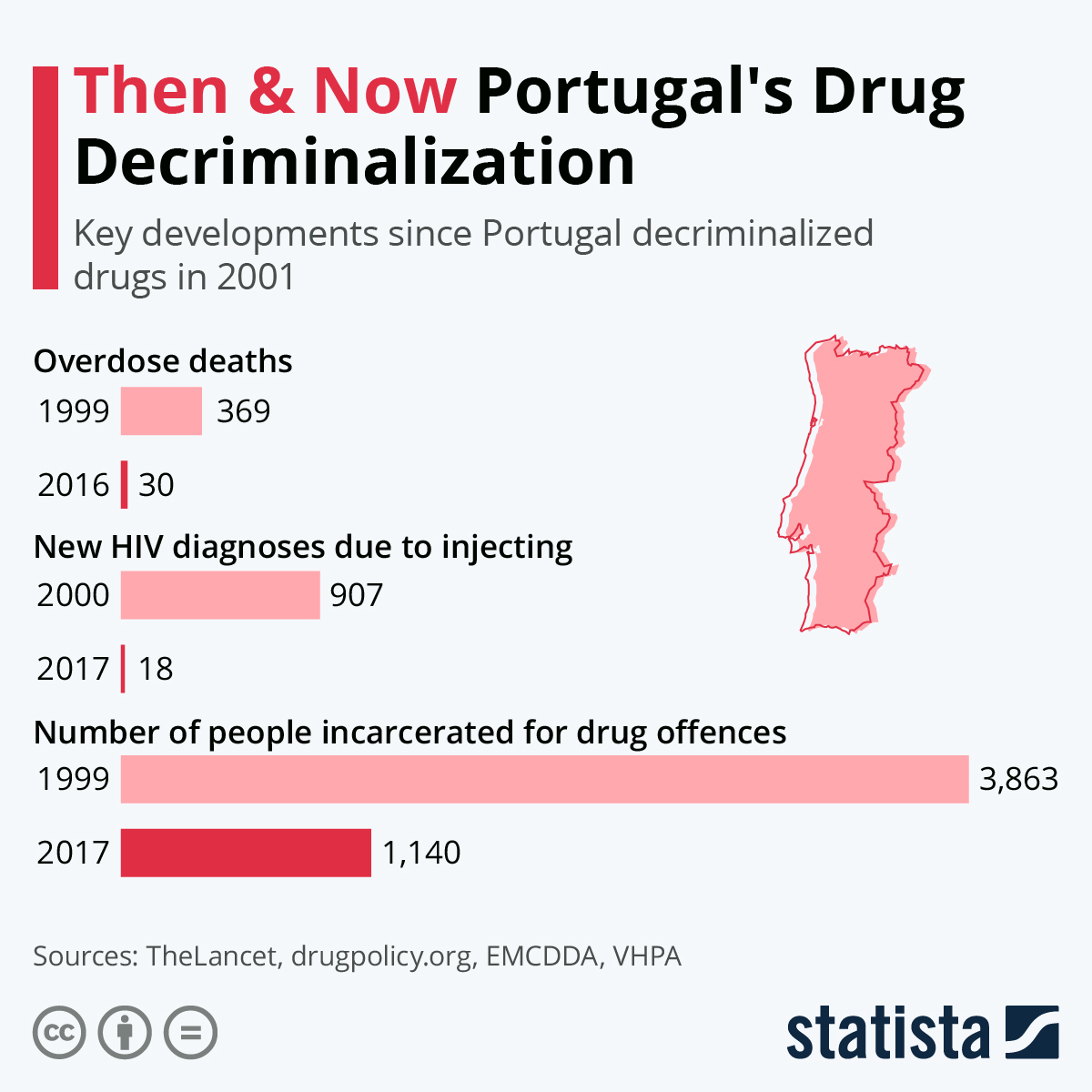

In 2001, Portugal decriminalized small amounts of all substances. This means the possession of substances for personal use and usage itself are still legally prohibited, but violations are exclusively administrative violations rather than criminal violations.[17]

If someone is using substances, they are not charged with substance related offences; rather anyone convicted of drug possession is sent for treatment, but the person may refuse treatment without any penalty.[18] Trafficking substances, on the other hand, is still illegal and can be prosecuted.[19] The Portuguese Government invested in treatment and evidence-based prevention programs.[20] It recognized that treatment costs far less than imprisonment.[21]

In Portugal, the number of people struggling with substance use disorders who chose to access treatment increased, there are treatment facilities readily available and there have been reductions in problematic use, substance use related harms and overcrowding in correctional facilities.[22] In Canada, access to treatment is provided by various provincial governments but access can be difficult as wait times for treatment is lengthy. For example, in Nova Scotia wait times for treatment, depending on the region, can last between 19-146 days.[23]

To learn more about Portugal’s approach please watch the video below.[24]

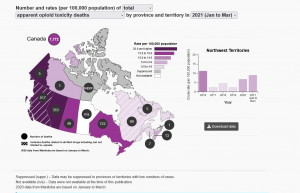

In Portugal, deaths related to substance use have reduced dramatically,[25] while in Canada, substance related deaths have increased, and almost 96% of opioid related overdose deaths were accidental.[26] Opioid deaths map of Canada.

Is Canada ready for decriminalization? Listen to Susan Boyd explore the current “war on drugs” in Canada.[27]

7.1B Activities

-

- Brainstorm all the reasons people might disagree with decriminalization. Are these reasons evidence based?

- Research one agency working on decriminalization in Canada.

- How can you promote an evidence-based public health approach to laws and substance use in Canada?

- Compare and contrast Canada, the Netherlands and Portgual’s approach to substance use laws and interventions.

The fears of many who saw Portugal as opening the door to an increase in substance use, increased infections, and harms have not happened. “Judging by every metric, decriminalization in Portugal has been a resounding success. It has enabled the Portuguese government to manage and control the drug problem far better than virtually every other Western country does”.[28]

Based on the statistics presented in the Netherlands and Portugal, laws and policies are best when they are evidence based.

7.1C Activity

Health Canada has updated its low-risk drinking guidelines. Please compare and contrast the proposed 2022 guidelines with the 2011 Guidelines.

2023 News story regarding the new guidelines

https://www.ctvnews.ca/health/what-you-should-know-about-canada-s-new-alcohol-guidelines-1.6239499[29]

2022 Proposed Guidelines

https://ccsa.ca/sites/default/files/2022-08/CCSA-LRDG-Update-of-Canada%27s-LRDG-Final-report-for-public-consultation-en.pdf[30]

2011 Guidelines

Chapter Credit

* Sections on The Netherlands and Portugal condensed and adapted from Unit 5.1 / Lessons from Other Societies in Drugs, Health & Behavior by Jacqueline Schwab. Content rewritten, references for stats added, chapter updated with Canadian content.

Image Credits

- Opioid deaths map of Canada from: Special Advisory Committee on the Epidemic of Opioid Overdoses. Opioid- and Stimulant-related Harms in Canada. Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada; March 2022. https://health-infobase.canada.ca/substance-related-harms/opioids-stimulants

- Key developments since Portugal decriminalized drugs in 2001 from: Statista. (2020). Then & now; Portugal’s drug decriminalization. https://www.statista.com/chart/20616/key-developments-since-portugal-decriminalized-drugs/

- Henry, B. (2018). Stopping the harm: Decriminalization of people who use drugs in BC. https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/health/about-bc-s-health-care-system/office-of-the-provincial-health-officer/reports-publications/special-reports/stopping-the-harm-report.pdf ↵

- Global Commission on Drug Policy. (2011). War on drugs: Report of the Global Commission on Drug Policy, (p. 3). https://www.globalcommissionondrugs.org/ ↵

- United Nations. (2016). General assembly special session on the world drug problem. https://www.unodc.org/documents/postungass2016/outcome/V1603301-E.pdf ↵

- European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. (2015). What is decriminalization of drugs? [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9NKhpujqOXc ↵

- UNAIDS. (2020, March 3). Decriminalization works, but too few countries are taking the bold step, (para. 3). https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/presscentre/featurestories/2020/march/20200303_drugs ↵

- Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs. (2008). FAQ drugs: A guide to drug policy. https://www.government.nl/topics/drugs ↵

- European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. (2019). Netherlands country drug report. https://www.emcdda.europa.eu/system/files/publications/11347/netherlands-cdr-2019.pdf ↵

- Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs. (2008). FAQ drugs: A guide to drug policy. https://www.government.nl/topics/drugs ↵

- European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. (2019). Netherlands country drug report. https://www.emcdda.europa.eu/system/files/publications/11347/netherlands-cdr-2019.pdf ↵

- Government of Canada. (2021). Opioid and stimulant-related harms in Canada. https://health-infobase.canada.ca/substance-related-harms/opioids-stimulants/ ↵

- European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction. (2019). Netherlands country drug report. https://www.emcdda.europa.eu/system/files/publications/11347/netherlands-cdr-2019.pdf ↵

- Ibid, p. 8 ↵

- Rotterman, M. (2021). Looking back from 2020, how cannabis use and related behaviours changed in Canada. Statistics Canada Health Reports. https://www.doi.org/10.25318/82-003-x202100400001-eng ↵

- Kalkman, G. A., Kramers, C., van Dongen, R. T. van den Brink, W., & Schellekens, A. (2019). Trends in use and misuse of opioids in the Netherlands: a retrospective, multi-source database study. The Lancet, 4(10). 498-505. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30128-8 ↵

- Canadian Centre for Substance Use and Addiction. (2020). Prescription opioids. https://www.ccsa.ca/sites/default/files/2020-07/CCSA-Canadian-Drug-Summary-Prescription-Opioids-2020-en.pdf ↵

- Government of Canada. (2021). Opioid and stimulant-related harms in Canada. https://health-infobase.canada.ca/substance-related-harms/opioids-stimulants/ ↵

- Greenwald, G. (2010). Drug decriminalization in Portugal: Lessons for creating fair and successful drug policies. CATO Institute Whitepaper Series, 1-38. https://ssrn.com/abstract=1464837 ↵

- Rego, X., Oliveria, M. J., Lameira, C., & Cruz, O. (2021). 20 years of Portuguese drug policy –developments, challenges and the quest for human rights. Substance Abuse Treatment Prevention Policy, 16(59). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-021-00394-7 ↵

- Greenwald, G. (2010). Drug decriminalization in Portugal: Lessons for creating fair and successful drug policies. CATO Institute Whitepaper Series, 1-38. https://ssrn.com/abstract=1464837 ↵

- Rego, X., Oliveria, M. J., Lameira, C., & Cruz, O. (2021). 20 years of Portuguese drug policy –developments, challenges and the quest for human rights. Substance Abuse Treatment Prevention Policy, 16(59). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-021-00394-7 ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Hughes, C. E., & Stevens, A. (2010). What can we learn from the Portuguese decriminalization of illicit drugs? The British Journal of Criminology, 50(6), 999–1022, https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azq038 ↵

- Nova Scotia Mental Health and Addictions. (2021). Wait time trends. https://waittimes.novascotia.ca/procedure/mental-health-addictions-adult-services#waittimes-tier3 ↵

- CBC News. (2017). How Portugal successfully tackled its drug crisis. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uQJ7n-JpcCk ↵

- Greenwald, G. (2010). Drug decriminalization in Portugal: Lessons for creating fair and successful drug policies. CATO Institute Whitepaper Series, 1-38. https://ssrn.com/abstract=1464837 ↵

- Government of Canada. (2021). Opioid and stimulant-related harms in Canada. https://health-infobase.canada.ca/substance-related-harms/opioids-stimulants/ ↵

- SFU Public Square. (2020, July 31). Susan Boyd: Colonial history and racial stereotypes are deeply entrenched in Canadian drug policy. [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8cEu2HfKy84\ ↵

- Hughes, C. E., & Stevens, A. (2010). What can we learn from the Portuguese decriminalization of illicit drugs? The British Journal of Criminology, 50(6), 999–1022, https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azq038 ↵

- What you should know about Canada's new alcohol guidelines ↵

- Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction. (2022). Update of Canada's low-risk alcohol drinking guidelines: final report for public consultation. https://ccsa.ca/update-canadas-low-risk-alcohol-drinking-guidelines-final-report-public-consultation-report ↵

- Government of Canada. (2019). Low-risk alcohol drinking guidelines. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/substance-use/alcohol/low-risk-alcohol-drinking-guidelines.html ↵