9.3 Harm Reduction Services in Canada

Harm reduction strategies can involve any of the following: safer use information, syringe distribution programs, education programs, opiate substitution programs, withdrawal management, safe consumption sites, peer helping and community development. Harm reduction access in Canada depends on the area in which one lives, for example, living in an urban area increase the chances to access harm reduction programs. Research suggests harm reduction services in Canada lack consistency as they are heavily dependent on the provincial governments; organizations lack continuous funding, must participate in a difficult application process for funds, and provinces and territories share different values when it comes to harm reduction.[1][2]

EXPLORE

Please review the interactive Opioid crisis map created by the Government of Canada which indicates harm reduction services focusing on the opioid crisis. Use the map to find locations of opioid-related activities taking place in communities across Canada.

It is not only service providers that are on the front line of harm reduction; it is also critical to acknowledge the work that has been done by the people who use substances. They have advocated for themselves, their peers, and their communities in the face of significant public backlash, threats of incarceration, and inaction on the part of federal, provincial and municipal governments. They have led the harm reduction movement in Canada; they deserve our gratitude: To those who have come before: we are in your debt.

Abstinence is not the goal of harm reduction; the goal is to support an individual wherever they may be on the spectrum of substance use. In this section, we will look at some of the more well-known harm reduction programs in Canada. This is by no means a comprehensive list of all harm reduction services across Canada; however, it offers Social Service workers a snapshot of programs that exist.

We discussed in Chapter 3 that alcohol is one of the most widely used substances in Canada; alcohol use is on a spectrum. Long term alcohol use has risks, for example average long-term consumption levels as low as one or two drinks per day have been causally linked with significant increases in the risk of at least eight types of cancer and numerous other serious medical conditions including pancreatitis, liver cirrhosis and hypertension.[3] Does this mean that everyone who drinks alcohol will develop one of these issues? No, however it increases the risk and when we include the intersectional factors including gender, race, trauma, and add disability, lack of affordable housing, incarceration, , and other social determinants of health, we increase the health risks again.

The Canadian Institute on Substance Use Research along with the University of Victoria are currently undertaking a review of harm reduction programs that support individuals with a dependency on alcohol, in particular (MAPs). People with severe alcohol dependence who engage in unsafe consumption (amount and consumption of non-beverage alcohol, like hand sanitizer or mouthwash) and a lack of housing are vulnerable to multiple harms.[4] Managed Alcohol Programs aim to reduce the harms to individuals who are at risk by providing a safe source of alcohol coupled with services which may include housing, counselling, healthcare, and peer support. “MAPs are harm reduction programs intended to reduce harms of high-risk drinking or severe alcohol use disorder often coupled with ongoing experiences of homelessness or poverty”.[5]

There are many different MAP programs in Canada “including community day programs, residential models located in shelters, transitional and permanent housing and hospital-based programs”.[6] Every program has different criteria, some address intersectional issues and are gender, race and age specific; nonetheless, all programs have the common goal of preserving dignity and reducing harms of drinking while increasing access to housing, health services, and cultural connections. MAPs have become an important part of harm reduction in Canada. Click here for a list of MAP sites in Canada.[7] This documentary by CBC highlights some of the individuals who utilize MAPs as well as the healthcare and shelter staff who support these individuals. Please click here to watch The Pour.[8]

Opiate use disorders may be managed by HAT. The first HAT in Canada began in 2005, North America Opiate Medication Initiative (NAOMI) which ran simultaneously in Vancouver and Montreal from 2005-2008[9] . Many participants were living in unstable housing and over 90% of participants had been engaged in some criminal activity during their lifetime.[10] Participants were given daily doses of prescription opiates and services to support their other health needs, a comprehensive range of psychosocial and primary care services.[11] There was also a control group which received Methadone Maintenance Therapy. The results showed a reduction in average spending on substances, a reduction in illicit-drug use or other illegal activities, an improvement in medical and psychiatric status, improvement in employment satisfaction, and family and social relations.[12] There was advocacy to continue the trial for compassionate reasons; however, this was denied by the Canadian Government. “After a year of receiving HAT, participants entered a three-month transition when they were offered a range of traditional treatments, including MMT and detox. After the three-month transitional period, no further treatment or supports were offered”.[13]

Opiate use in Canada has been called a crisis[14] and in April 2016, a public health emergency was announced in British Columbia. According to the Government of Canada, there were 22,828 apparent opioid toxicity deaths between January 2016 and March 2021. Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, 6,946 apparent opioid toxicity deaths occurred (April 2020 to March 2021), representing an 88% increase from the same period prior to the pandemic.[15] The National Harm Reduction Coalition (2021)[16] suggests there are between 75,000-125,000 people in Canada who are injecting substances, which increases risks of HIV/Hepatitis as well as other blood borne illnesses, bacterial infections, abscesses, and vein collapse. There is much information on safe injection use; however, the risks still exist.

People who have an opiate use disorder come from all walks of life. Opiate use disorder is “a chronic relapsing disease and is often accompanied by abuse of other psychoactive drugs, physical and mental health problems, and severe social marginalization”.[17] For some individuals, abstinence is not an option. Though there are programs like methadone maintenance therapy (MMT), as discussed in Chapter 8, these programs are not universally accessible and not universally successful.[18]

A network of individuals who had participated in NAOMI, a heroin assisted treatment program discussed in Chapter 8 gathered in 2011 to discuss their experiences and this work was collected by Dr. Susan Boyd, culminating in the creation of NAOMI Research Survivors: Experiences and Recommendations.[19] Please review the guide.

The recommendations from NAOMI participants are listed here:

- When experimental substance maintenance programs are over, clients (research subjects), for compassionate reasons should receive the drug they were on as long as they need it.

- An ideal study would provide an umbrella of support and services including

-

- housing (most important)

- access to medical treatments all under one roof (nurses, doctors, dentists)

- access to welfare workers (who are familiar with the area and the people who live there) and ministry representatives

- access to nutritious food for self and family

- support to move life forward (school, trade, family unification)

- access to lawyers

- education/advocacy skills and access to advocates

- diverse routes of administration available – oral, smoking form, injection. Not all people want to inject their drug.

This project and the subsequent recommendations helped many working in harm reduction gain a deeper understanding of the research process and the ethics of studies on individuals who use substances.

Food For Thought

- Why would an individual participate in a study like NAOMI?

- What are the ethical concerns with NAOMI?

- After reviewing the positive outcomes, why was NAOMI stopped?

- What would it take to develop a HAT program in your community?

Providence Health in British Columbia continued this work and launched the Study to Assess Longer-term Opioid Medication Effectiveness (SALOME), which concluded in 2016. This was a clinical trial that tested alternative treatments, specifically prescription opiates, for people with chronic opiate use disorders who were not benefitting from currently known treatments.[20] From the success of participants during both the NAOMI and SALOME studies, the courts decided that those who were continuing to benefit from HAT could continue receiving their treatment, though the research was concluded in 2016.[21][22] There is no current HAT program in Canada.

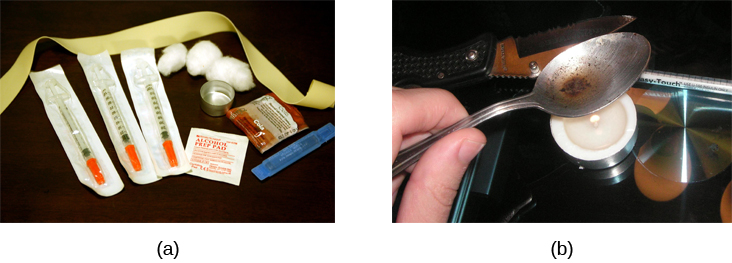

Syringe distribution programs offer clean syringes, alcohol swabs, cookers, water, cottons, all the materials one would need to inject more safely. They also provide safer injection information including safer injection places on the body, vein care, and when to get help. They provide condoms and safer sex information to reduce risks of sexually transmitted infections. They provide a safe space to build relationships, and for those who want to move towards a reduction in use or abstinence, staff at SDP can make referrals to various treatment options. Being a first point of contact has a tremendous amount of responsibility; Social Service workers should have a good understanding of services in their community.

In Vancouver, the epicentre of the HIV crisis in the 1990’s, individuals and agencies were advocating for the development of safer injection. Syringe distribution programs (SDP) began to reduce the spread of blood borne illnesses, including HIV, and since 2018 the Canadian Government has endorsed syringe distribution programs as an effective harm reduction strategy through the pillars of the Canadian Drug and Substances Strategy. Research continues to support the benefit of SDP including a reduction in HIV transmission.[23] Syringe distribution is more than just reduction of HIV; through providing a clean needle, it may be the first point of access to a non-judgmental health service for an individual.

In Nova Scotia, there are a number of syringe distribution programs. Mainline Needle Exchange has a rich history of providing harm reduction/health promotion services in Nova Scotia including the provision of needles, syringes, other drug use supplies, and condoms; the collection and appropriate disposal of needles; awareness and education on harm reduction practices related to safer injection and sexual practices and general health; and the provision of peer support by people in recovery.[24] A program of the Mi’kmaq Native Friendship Centre, Mainline began providing harm reduction services in 1992 in response to an identified need in the community.[25] Other syringe distribution services in Atlantic Canada include but are not limited to:

- Ally Centre of Cape Breton

- AIDS Committee of Newfoundland and Labrador, Safe Works Access Program

- AIDS New Brunswick

Internationally more than 65 Safe Injection Sites (SIS) have been opened as part of harm reduction strategies associated with substance use.[26] Also known as safe consumption sites (SCS), these facilities have been an important part of the harm reduction landscape, particularly in Western Canada since the advent of the HIV crisis and most recently the ongoing public health crisis of opioid overdoses and death.[27] SIS are places where people can more safely inject substances using clean equipment under the supervision of medically trained personnel which reduces the risk of overdose and blood borne illnesses. It also allows individuals who may not have had any positive connection to healthcare or other support services to build relationships if they choose. Most SIS have expanded their mandate to include various forms of consumption. What if substance use is hidden? In rural areas substance use is not always seen in public, which may challenge communities to acknowledge the substance use of its residents.

Food For Thought

- Does Nova Scotia have an SIS?

- Is safe consumption an issue in NS?

- What services should be provided in a local SIS?

- Should all communities have access to SIS? Why? Why not?

- What types of challenges may exist in the development of a SIS in your community?

- Any idea on how to deal with the challenges?

A common question is whether the site provides the substances. The answer is a resounding no, the substances are not provided by anyone at the facility but are brought there by the individuals who use the service. Most SIS are located in areas where there is a high prevalence of substance abuse and researchers suggest SIS should be developed in areas where injection use and overdose are common.[28] The SIS workers help to create a safer space for individuals to use their substance, providing safe equipment, referrals to support services, and in the case of an overdose, medically trained staff to treat the overdose. Many SIS provide “peer assistance.”

Peer assistance refers to one person providing assistance to another in the course of preparing and consuming drugs. Those requiring peer assistance often include women, people with disabilities or illness, and other vulnerable populations. Friends or other clients may help assist, but employees of a supervised consumption site do not directly administer the drugs.[29]

Beyond the services provided regarding preventing overdose and illness, people who use substances are at risk when using in a public area; these risks include being caught by police, being physically or sexually assaulted, or robbed.[30] Having a safe place to go reduces those risks. One of the ways SIS are helping to reduce the risk of accidental overdose is using testing kits. People can bring in their substance, have it tested, get information on what is in their substance, which helps them make a more-informed decision about what they use.[31] This is a necessity in Canada when substances are bought and sold in the black market. Without regulation, there is risk when you purchase a substance. SIS provide testing kits to prevent overdose and illness. To learn more, please read the following article about testing kit expansion in Saskatchewan. Province expands testing kits.

InSite, a service of PHS Community Services Society, a large non-profit organization in British Columbia, is one of the best known SIS facilities in Canada. InSite was the first safer injection site in Canada. Since its inception, InSite has provided 6,440 overdose interventions without any deaths.[32] InSite has also expanded their services to provide safer consumption, which includes more than just injection but the safer consumption of substances that can be taken by other routes of administration, for example, inhalation. InSite has also developed OnSite, a withdrawal management and recovery program.

Please watch the video Inside Insite. and take a virtual tour of InSite.[33]

What is the difference between a supervised consumption/supervised injection site and an overdose prevention site (OPS)?

Internationally more than 65 Safe Injection Sites (SIS) have been opened as part of harm reduction strategies associated with substance use.[34] Also known as safe consumption sites (SCS), these facilities have been an important part of the harm reduction landscape, particularly in Western Canada since the advent of the HIV crisis and most recently the ongoing public health crisis of opioid overdoses and death.[35] SIS are places where people can more safely inject substances using clean equipment under the supervision of medically trained personnel which reduces the risk of overdose and blood borne illnesses. It also allows individuals who may not have had any positive connection to healthcare or other support services to build relationships if they choose. Most SIS have expanded their mandate to include various forms of consumption. What if substance use is hidden? In rural areas substance use is not always seen in public, which may challenge communities to acknowledge the substance use of its residents.

They are generally staffed by peers and harm reduction workers.[36] OPS are not required to have health care professionals on staff and are considered “pop-up” as they are a mobile response to overdose prevention. In September of 2019, Atlantic Canada’s first government approved OPS opened in the basement of Direction 180, a Methadone Maintenance Program in Halifax, due to the lobbying efforts of numerous harm reduction agencies in Nova Scotia. OPS’s have made an impact across Canada; nonetheless, there is limited research on OPSs.[37] OPS are a very low-barrier harm reduction service.

9.3A Activities

- Research SIS and OPS. What are the similarities and differences?

- What is the process to apply for an exemption of the CDSA for an SIS? OPS?

- How long can an OPS operate?

- Who funds an OPS?

- How can you support an OPS?

- Read the following article.

Atlantic Canada’s first overdose prevention set to open in Halifax by Alexa MacLean. Posted July 17, 2019 to Global News. - What is one learning?

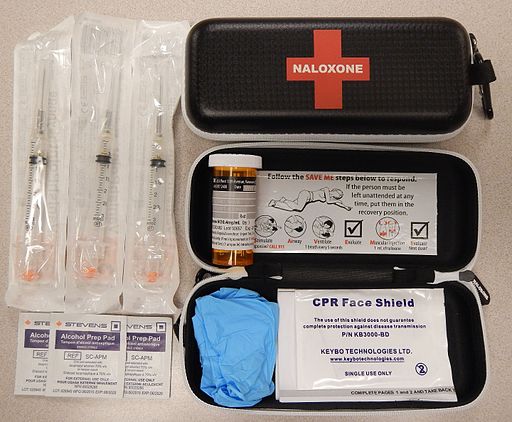

As of October 23, 2021, 33 Nova Scotian’s lost their life to overdose.[38] One way to prevent overdose deaths, as part of a comprehensive harm reduction strategy, is to ensure individuals and communities have access to an opioid antagonist to an opioid overdose.

In 2017, the Nova Scotia Department of Health and Wellness recognized individuals using opioids and their family and peer groups must have access to naloxone and created the Nova Scotia Take Home Naloxone Program.[39] The program “provides opioid overdose prevention/naloxone administration training and free take home naloxone kits to Nova Scotians at risk of an opioid overdose and those who are most likely to witness and respond to an opioid overdose”.[40]

9.3B Activities

- What increases the risk of an opiate overdose?

- Other than naloxone, how can communities help prevent overdose?

- Where would someone go for naloxone in your community?

Food For Thought

- Why would some pilot projects on substance use disorders do not get funded?

- What is the role of media in sharing information?

- What is the role of activism/advocacy?

Click on the following link for more information on how to respond to an overdose http://www.nsnaloxone.com/uploads/1/1/2/0/112043611/naloxone_-_how_to_prepare_final__110.mp4

Naloxone kits are just one component; helping individuals understand the risks of using a substance alone is another arm of naloxone.

Please watch the video How to Spot Someone so They Never Use Alone.[41]

There are many forms of harm reduction and many harm reduction programs in Canada. Harm reduction is an important pillar in healthcare for people who use substances.

Image Credits

- Hear Us, See Us, Respect Us Poster from: Touesnard, Natasha, Patten, San, McCrindle, Jenn, Nurse, Michael, Vanderschaeghe, Shay, Noel, Wyatt, Edward, Joshua, & Blanchet- Gagnon, Marie-Anik. (2021). Hear Us, See Us, Respect Us: Respecting the Expertise of People who Use Drugs (3.0). Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5514066

- Needle exchange kit by Todd Huffman via Wikimedia Commons shared under CC BY 2.0 license.

- Converting Heroin Tar into “Monkey Water” by Psychonaught via Wikimedia Commons Public domain image.

- Mainline Needle Exchange. (2021). Loading supplies into the trunk of a car [image]. About us. https://mainlineneedleexchange.ca/about-us/

- Naloxone kits as distributed in British Columbia by James Heilman via Wikimedia Commons shared under a CC BY-SA license.

- Hyshka, E., Anderson-Baron, J., Karekezi, K., Belle-Isle L., Elliott, R., Pauly, B., Strike, C., Asbridge, M., Dell, C., McBride, K., Hathaway, A., & Wild, T. C. (2017). Harm reduction in name, but not substance: a comparative analysis of current Canadian provincial and territorial policy frameworks. Harm Reduction Journal, 14(1), 50. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-017-0177-7 ↵

- Cavalieri, W., & Riley D (2012). Harm reduction in Canada: The many faces of regression. In Pates & D. Riley (Eds.), Harm reduction in substance use and high risk behaviour: international policy and practice (pp. 392–394). Wiley-Blackwell. ↵

- Butt, P., Beirness, D., Cesa, F., Gliksman, L., Paradis, C., & Stockwell, T. (2011). Alcohol and health in Canada: A summary of evidence and guidelines for low-risk drinking. Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse. https://www.uvic.ca/research/centres/cisur/assets/docs/report-alcohol-and-health-in-canada.pdf ↵

- Pauly B. B., Reist, D., Belle-Isle, L., & Schactman, C. (2013). Housing and harm reduction: What is the role of harm reduction in addressing homelessness? International Journal on Drug Policy, 24(4), 284–290. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23623720/ ↵

- Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research. (n.d.). Scale up of managed alcohol programs. Bulletin #20. 1-4. https://www.uvic.ca/research/centres/cisur/assets/docs/bulletin-20-scale-up-of-maps.pdf ↵

- Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research. (n.d.). Scale up of managed alcohol programs. Bulletin #20. 1-4. https://www.uvic.ca/research/centres/cisur/assets/docs/bulletin-20-scale-up-of-maps.pdf ↵

- Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research. (2021). Overview of Managed Alcohol Program (MAP) sites in Canada (and beyond). https://www.uvic.ca/research/centres/cisur/assets/docs/resource-overview-of-MAP-sites-in-Canada.pdf ↵

- CBC. (2016). The Fifth Estate: The Pour. https://www.cbc.ca/player/play/849395779835 ↵

- Oviedo-Joekes, E., Nosyk, B., Brissette, S., Chettiar, J., Schneeberger, P., Marsh, D. C., Krausz, M., Anis, A., & Schechter, M. T. (2008). The North American Opiate Medication Initiative (NAOMI): Profile of participants in North America's first trial of heroin-assisted treatment. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 85(6), 812–825. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-008-9312-9 ↵

- Oviedo-Joekes, E., Nosyk, B., Brissette, S., Chettiar, J., Schneeberger, P., Marsh, D. C., Krausz, M., Anis, A., & Schechter, M. T. (2008). The North American Opiate Medication Initiative (NAOMI): Profile of participants in North America's first trial of heroin-assisted treatment. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 85(6), 812–825. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-008-9312-9 ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Berridge, V. (2009). Heroin prescription and history. The New England Journal of Medicine, 361, 820-821. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1056/NEJMe0904243 ↵

- The NAOMI Patients Association & Boyd, S. (2012). NAOMI research survivors; experiences and recommendations (p. 20). https://drugpolicy.ca/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/NPAreportMarch5-12.pdf ↵

- Government of Canada. (2021, Sept. 22). Opioid- and stimulant-related harms in Canada. https://health-infobase.canada.ca/substance-related-harms/opioids-stimulants/ ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- The National Harm Reduction Coalition. (2021). Priniciples of harm reduction. https://harmreduction.org/ ↵

- Van den Brink, W., & Haasen, C. (2006). Evidenced-based treatment of opioid-dependent patients. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 51, 635–646. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674370605101003 ↵

- Goldstein, M. F., Deren, S., Kang, S. Y., Des Jarlais, D. C., & Magura, S. (2002). Evaluation of an alternative program for MMTP drop-outs: Impact on treatment re-entry. Drug Alcohol Dependence, 66, 181–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0376-8716(01)00199-5 ↵

- The NAOMI Patients Association & Boyd, S. (2012). NAOMI research survivors; experiences and recommendations. https://drugpolicy.ca/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/NPAreportMarch5-12.pdf ↵

- Providence Health Care. 2016. SALOME. https://www.providencehealthcare.org/salome/about-us.html ↵

- Canadian Drug Policy. (2021). Heroin assisted treatment. https://drugpolicy.ca/our-work/issues/heroin-assisted-treatment/ ↵

- Providence Health Care. 2016. SALOME. https://www.providencehealthcare.org/salome/about-us.html ↵

- Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technology in Health. (2015). Needle exchange programs in a community setting: A review of the clinical and cost-effectiveness. https://cadth.ca/sites/default/files/pdf/htis/2017/RC0705%20Needle%20Exchange%20in%20Community%20Final.pdf ↵

- Atlantic Interdisciplinary Research Network. (2016). Program evaluation for Mainline Needle Exchange: Contributing to a harm reduction landscape in Nova Scotia. http://www.airn.ca/uploads/8/6/1/4/86141358/mainline_evaluation_report_final_2027.pdf ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Marshall, B. D., Milloy, M. J., Wood, E., Montaner, J. S., & Kerr, T. (2011). Reduction in overdose mortality after the opening of North America's first medically supervised safer injecting facility: a retrospective population-based study. The Lancet, 377(9775), 1429-1437. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62353-7 ↵

- Government of Canada. (2021, Sept. 22). Opioid- and stimulant-related harms in Canada. https://health-infobase.canada.ca/substance-related-harms/opioids-stimulants/ ↵

- Marshall, B. D., Milloy, M. J., Wood, E., Montaner, J. S., & Kerr, T. (2011). Reduction in overdose mortality after the opening of North America’s first medically supervised safer injecting facility: a retrospective population-based study. The Lancet, 377(9775), 1429-1437. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62353-7 ↵

- Government of Canada. (2021, Nov. 11). Supervised consumption sites: Status of applications.https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/substance-use/supervised-consumption-sites/status-application.html ↵

- Green, T. C., Hankins, C. A., Palmer, D., Boivin, J. F., & Platt, R. (2004). My place, your place or a safer place: The intention among Montreal injecting drug users to use SIF. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 95(2),110-114. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41994109 ↵

- Maghsoudi, N., Tanguay, J., Scarfone, K., Rammohan, I., Ziegler, C., Werb, D., & Scheim, A. (2021). The implementation of drug checking services for people who use drugs: A systematic review. Qeios. https://doi.org/10.32388/TXE86U ↵

- Vancouver Coastal Health. (2020). Supervised consumption sites. http://www.vch.ca/public-health/harm-reduction/supervised-consumption-sites ↵

- National Film Board of Canada (2017, May 26). Inside Insite. [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7gIyBMt2BEk ↵

- Marshall, B. D., Milloy, M. J., Wood, E., Montaner, J. S., & Kerr, T. (2011). Reduction in overdose mortality after the opening of North America's first medically supervised safer injecting facility: a retrospective population-based study. The Lancet, 377(9775), 1429-1437. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62353-7 ↵

- Government of Canada. (2021, Nov. 11). Supervised consumption sites: Status of applications. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/substance-use/supervised-consumption-sites/status-application.html ↵

- Pauly, B., Wallace, B., Pagan, F., Phillips, J., Wilson, M., Hobbs, H., & Connolly, J. (2020). Impact of overdose prevention sites during a public health emergency in Victoria, Canada. PLoS One, 15(5). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0229208 ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Government of Nova Scotia. (2021). Nova Scotia take home naloxone program. http://www.nsnaloxone.com/about-the-program.html ↵

- Government of Nova Scotia. (2021). Nova Scotia take home naloxone program. http://www.nsnaloxone.com/about-the-program.html ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Canadian Association of People who Use Drugs. (2021). How to spot someone so they never use alone. [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=3&v=KbUwb-pszW4&feature=emb_logo ↵