The Humanistic, Contextual, and Evolutionary Perspectives of Development

What you’ll learn to do: describe the humanistic, contextual, and evolutionary perspectives of development

Each perspective that we have seen so far emphasizes different aspects of development. We first looked at the psychodynamic approach and how it emphasizes unconscious determinants of behavior. We then turned to the behavioral perspective which emphasizes overt behavior. Now, we’ll turn our attention to the humanistic perspective, which emphasizes empathy and stresses the good in human behavior; it is similar to the cognitive perspective in that it looks more at what people think than at what they do. In this section, we will also look at the contextual perspective, which considers the relationship between individuals and their physical world, cognitive processes, personality, and social worlds. It also examines social and cultural influences on development. And finally, we will briefly examine the evolutionary perspective which focuses on how inherited biological factors underlie development.

Learning Outcomes

- Describe the major concepts of humanistic theory (unconditional positive regard, the good life), as developed by Carl Rogers

- Explain Maslow’s hierarchy of needs

- Describe Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory of cognitive development

- Explain Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological model

- Describe the evolutionary perspective

- Contrast the main psychological theories that apply to human development

The Humanistic Perspective: A focus on Uniquely Human Qualities

The humanistic perspective rose to prominence in the mid-20th century in response to psychoanalytic theory and behaviorism; this perspective focuses on how healthy people develop and emphasizes an individual’s inherent drive towards self-actualization and creativity. Humanism emphasizes human potential and an individual’s ability to change, and rejects the idea of biological determinism. Humanistic work and research are sometimes criticized for being qualitative (not measurement-based), but there exist a number of quantitative research strains within humanistic psychology, including research on happiness, self-concept, meditation, and the outcomes of humanistic psychotherapy (Friedman, 2008).

Carl Rogers and Humanism

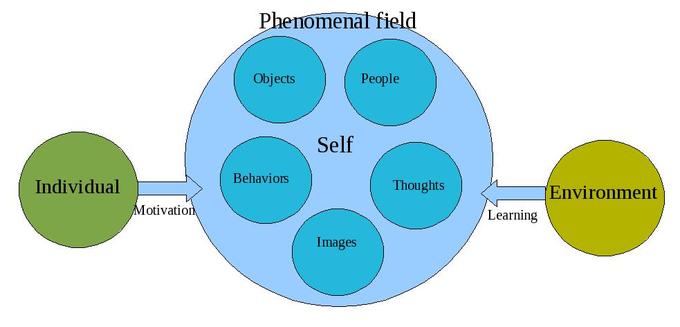

One pioneering humanistic theorist was Carl Rogers. He was an influential humanistic psychologist who developed a personality theory that emphasized the importance of the self-actualizing tendency in shaping human personalities. He also believed that humans are constantly reacting to stimuli with their subjective reality (phenomenal field), which changes continuously. Over time, a person develops a self-concept based on the feedback from this field of reality.

One of Rogers’s main ideas about personality regards self-concept, our thoughts and feelings about ourselves. How would you respond to the question, “Who am I?” Your answer can show how you see yourself. If your response is primarily positive, then you tend to feel good about who you are, and you probably see the world as a safe and positive place. If your response is mainly negative, then you may feel unhappy with who you are. Rogers further divided the self into two categories: the ideal self and the real self. The ideal self is the person that you would like to be; the real self is the person you actually are. Rogers focused on the idea that we need to achieve consistency between these two selves.

Unconditional Positive Regard

Human beings develop an ideal self and a real self, based on the conditional status of positive regard. How closely one’s real self matches up with their ideal self is called congruence. We experience congruence when our thoughts about our real self and ideal self are very similar—in other words when our self-concept is accurate. High congruence leads to a greater sense of self-worth and a healthy, productive life. Conversely, when there is a great discrepancy between our ideal and actual selves, we experience a state Rogers called incongruence, which can lead to maladjustment.

According to Rogers, parents can help their children achieve their ideal self by giving them unconditional positive regard, or unconditional love. In the development of self-concept, positive regard is key. Unconditional positive regard is an environment that is free of preconceived notions of value. Conditional positive regard is full of conditions of worth that must be achieved to be considered successful. Rogers (1980) explained it this way: “As persons are accepted and prized, they tend to develop a more caring attitude towards themselves” (p. 116).

The Good Life

Rogers described life in terms of principles rather than stages of development. These principles exist in fluid processes rather than static states. He claimed that a fully functioning person would continually aim to fulfill his or her potential in each of these processes, achieving what he called “the good life”. These people would allow personality and self-concept to emanate from experience. He found that fully functioning individuals had several traits or tendencies in common:

- A growing openness to experience–they move away from defensiveness.

- An increasingly existential lifestyle–living each moment fully, rather than distorting the moment to fit personality or self-concept.

- Increasing organismic trust–they trust their own judgment and their ability to choose behavior that is appropriate for each moment.

- Freedom of choice–they are not restricted by incongruence and are able to make a wide range of choices more fluently. They believe that they play a role in determining their own behavior and so feel responsible for their own behavior.

- Higher levels of creativity–they will be more creative in the way they adapt to their own circumstances without feeling a need to conform.

- Reliability and constructiveness–they can be trusted to act constructively. Even aggressive needs will be matched and balanced by intrinsic goodness in congruent individuals.

- A rich full life–they will experience joy and pain, love and heartbreak, fear and courage more intensely.

Try It

Abraham Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Abraham Maslow (1908–1970) was an American psychologist who is best known for proposing a hierarchy of human needs in motivating behavior. Maslow described a pattern through which human motivations generally move, meaning that in order for motivation to occur at the next level, each level must be satisfied within the individual themselves. These stages include:

- physiological needs: the main physical requirements for human survival, including homeostasis, food, water, sleep, shelter, and sex.

- safety needs: the need for personal, emotional, financial, and physical security. Once a person’s physiological needs are relatively satisfied, their safety needs take precedence and dominate behavior. In the absence of physical safety – due to war, natural disaster, family violence, childhood abuse, institutional racism, etc. – people may (re-)experience post-traumatic stress disorder or transgenerational trauma. In the absence of economic safety – due to an economic crisis and lack of work opportunities – these safety needs manifest themselves in ways such as a preference for job security, grievance procedures for protecting the individual from unilateral authority, savings accounts, insurance policies, disability accommodations, etc. This level is more likely to predominate in children as they generally have a greater need to feel safe.

- love and belonging: the need for friendships, intimacy, and belonging. This need is especially strong in childhood and it can override the need for safety as witnessed in children who cling to abusive parents. Deficiencies within this level of Maslow’s hierarchy – due to hospitalism, neglect, shunning, ostracism, etc. – can adversely affect the individual’s ability to form and maintain emotionally significant relationships in general.

- esteem: the typical human desire to be accepted and valued by others. People often engage in a profession or hobby to gain recognition. Esteem needs are ego needs or status needs. People develop a concern with getting recognition, status, importance, and respect from others. Most humans have a need to feel respected; this includes the need to have self-esteem and self-respect.

- self-actualization: Maslow describes this level as the desire to accomplish everything that one can, to become the most that one can be. Individuals may perceive or focus on this need very specifically. For example, one individual may have a strong desire to become an ideal parent. In another, the desire may be expressed athletically. For others, it may be expressed in paintings, pictures, or inventions. Some examples of this include utilizing abilities and talents, pursuing goals, and seeking happiness.

Furthermore, this theory is a key foundation in understanding how drive and motivation are correlated when discussing human behavior. Each of these individual levels contains a certain amount of internal sensation that must be met in order for an individual to complete their hierarchy. The goal in Maslow’s theory is to attain the fifth level or stage of self-actualization.

Watch It

Watch as Maslow’s hierarchy of needs comes to life in this quick video.

Try It

Contextual Perspectives: A Broad Approach to Development

The contextual perspective considers the relationship between individuals and their physical, cognitive, and social worlds. It also examines socio-cultural and environmental influences on development. We will focus on two major theorists who pioneered this perspective: Lev Vygotsky and Urie Bronfenbrenner. Lev Vygotsky was a Russian psychologist who is best known for his sociocultural theory. He believed that social interaction plays a critical role in children’s learning; through such social interactions, children go through a continuous process of scaffolded learning. Urie Bronfenbrenner developed the ecological systems theory to explain how everything in a child and the child’s environment affects how a child grows and develops. He labeled different aspects or levels of the environment that influence children’s development.

Vygotsky’s Sociocultural Theory: Changes in thought with guidance

Modern social learning theories stem from the work of Russian psychologist Lev Vygotsky, who produced his ideas as a reaction to existing conflicting approaches in psychology (Kozulin, 1990). Vygotsky’s ideas are most recognized for identifying the role of social interactions and culture in the development of higher-order thinking skills. His theory is especially valuable for the insights it provides about the dynamic “interdependence between individual and social processes in the construction of knowledge” (John-Steiner & Mahn, 1996, p. 192). Vygotsky’s views are often considered primarily as developmental theories, focusing on qualitative changes in behavior over time as attempts to explain unseen processes of development of thought, language, and higher-order thinking skills. Although Vygotsky’s intent was mainly to understand higher psychological processes in children, his ideas have many implications and practical applications for learners of all ages.

Three themes are often identified with Vygotsky’s ideas of sociocultural learning: (1) human development and learning originate in social, historical, and cultural interactions, (2) use of psychological tools, particularly language, mediate development of higher mental functions, and (3) learning occurs within the Zone of Proximal Development. While we discuss these ideas separately, they are closely interrelated, non-hierarchical, and connected.

Vygotsky’s sociocultural theory emphasizes the importance of culture and interaction in the development of cognitive abilities. Vygotsky contended that thinking has social origins, social interactions play a critical role especially in the development of higher-order thinking skills, and cognitive development cannot be fully understood without considering the social and historical context within which it is embedded. He explained, “Every function in the child’s cultural development appears twice: first, on the social level, and later, on the individual level; first between people (interpsychological) and then inside the child (intrapsychological)” (Vygotsky, 1978, p. 57). It is through working with others on a variety of tasks that a learner adopts socially shared experiences and associated effects and acquires useful strategies and knowledge (Scott & Palincsar, 2013).

Rogoff (1990) refers to this process as guided participation, where a learner actively acquires new culturally valuable skills and capabilities through a meaningful, collaborative activity with an assisting, more experienced other. It is critical to notice that these culturally mediated functions are viewed as being embedded in sociocultural activities rather than being self-contained. Development is a “transformation of participation in a sociocultural activity” not a transmission of discrete cultural knowledge or skills (Matusov, 2015, p. 315).

Scaffolding and the Zone of Proximal Development

Vygotsky differed with Piaget in that he believed that a person not only has a set of abilities, but also a set of potential abilities that can be realized if given the proper guidance from others. He believed that through guided participation known as scaffolding, with a teacher or capable peer, a child can learn cognitive skills within a certain range known as the zone of proximal development. While Piaget’s ideas of cognitive development assume that development through certain stages is biologically determined, originates in the individual, and precedes cognitive complexity, Vygotsky presents a different view in which learning drives development. The idea of learning driving development, rather than being determined by the developmental level of the learner, fundamentally changes our understanding of the learning process and has significant instructional and educational implications (Miller, 2011).

Have you ever taught a child to perform a task? Maybe it was brushing their teeth or preparing food. Chances are you spoke to them and described what you were doing while you demonstrated the skill and let them work along with you throughout the process. You gave them assistance when they seemed to need it, but once they knew what to do-you stood back and let them go. This is scaffolding. This approach to teaching has also been adopted by educators. Rather than assessing students on what they are doing, they should be understood in terms of what they are capable of doing with the proper guidance.

This difference in assumptions has significant implications for the design and development of learning experiences. If we believe as Piaget did that development precedes learning, then we will make sure that new concepts and problems are not introduced until learners have developed innate capabilities to understand them. On the other hand, if we believe as Vygotsky did that learning drives development and that development occurs as we learn a variety of concepts and principles, recognizing their applicability to new tasks and new situations, then our instructional design will look very different.

Watch It

Watch this video to learn more about Vygotsky’s theory of sociocultural development.

Try It

Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory

Another psychologist who recognized the importance of the environment on development was American psychologist, Urie Bronfenbrenner (1917-2005), who formulated the ecological systems theory to explain how the inherent qualities of a child and their environment interact to influence how they will grow and develop. The term “ecological” refers to a natural environment; human development is understood through this model as a long-lasting transformation in the way one perceives and deals with the environment. Bronfenbrenner’s ecological theory stresses the importance of studying children in the context of multiple environments because children typically find themselves enmeshed simultaneously in different ecosystems. Each of these systems inevitably interact with and influence each other in every aspect of the child’s life, from the most intimate level to the broadest. Furthermore, he eventually renamed his theory the bioecological model in order to recognize the importance of biological processes in development. However, he only recognized biology as producing a person’s potential, with this potential being realized or not via environmental and social forces.

An individual is impacted by microsystems such as parents or siblings; those who have direct, significant contact with the person. The input of those people is modified by the cognitive and biological state of the individual as well. These influence the person’s actions, which in turn influence systems operating on them. The mesosystem includes larger organizational structures such as school, the family, or religion. These institutions impact the microsystems just described. For example, the religious teachings and traditions of a family may create a climate that makes the family feel stigmatized and this indirectly impacts the child’s view of their self and others. The philosophy of the school system, daily routine, assessment methods, and other characteristics can affect the child’s self-image, growth, sense of accomplishment, and schedule, thereby impacting the child physically, cognitively, and emotionally. These mesosystems both influence and are influenced by the larger contexts of the community, referred to as the exosystem. A community’s values, history, and economy can impact the organizational structures it houses. And the community is influenced by macrosystems, which are cultural elements such as global economic conditions, war, technological trends, values, philosophies, and a society’s responses to the global community. In sum, a child’s experiences are shaped by larger forces such as the family, school, religion, and culture. All of this occurs within the relevant historical context and timeframe, or chronosystem. The chronosystem is made up of the environmental events and transitions that occur throughout a child’s life, including any socio-historical events. This system consists of all the experiences that a person has had during their lifetime.

Watch It

This short video from Professor Rachelle Tannenbaum of Anne Arundel Community College explains and gives examples of Brofenbrenner’s theory.

Try It

The Evolutionary Perspective: Genetic Inheritance from our Ancestors

The fundamentals of the evolutionary perspective

One very influential approach in understanding human development is the evolutionary perspective, the final developmental perspective that we will consider. This perspective seeks to identify behavior that is the result of our genetic inheritance from our ancestors. Evolutionary psychology is a theoretical approach in the social and natural sciences that examines psychological structure from a modern evolutionary perspective. It seeks to identify which human psychological traits are evolved adaptations – that is, the functional products of natural selection or sexual selection in human evolution.

David M. Buss is an evolutionary psychologist at the University of Texas at Austin, theorizing and researching human sex differences in mate selection. The primary topics of his research include male mating strategies, conflict between the sexes, social status, social reputation, prestige, the emotion of jealousy, homicide, anti-homicide defenses, and most recently, stalking. All of these are approached from an evolutionary perspective.

Evolutionary psychology has its historical roots in Charles Darwin’s theory of natural selection. In The Origin of Species, Darwin predicted that psychology would develop an evolutionary basis, and that a process of natural selection creates traits in a species that are adaptive to its environment.

Using Darwin’s arguments, evolutionary approaches claim that one’s genetic inheritance not only determine such physical traits as skin and eye color, but also certain personality traits and social behaviors. For example, some evolutionary developmental psychologists suggest that behavior such as shyness and jealousy may be produced in part by genetic causes, presumably because they helped increase the survival rates of human’s ancient relatives.[1][2][3]

Lorenz and Imprinting

The evolutionary perspective draws heavily on the field of ethology, which examines the ways in which our biological makeup influences our behavior. The primary proponent of ethology was Konrad Lorenz, who discovered that newborn geese are genetically pre-programmed to become attached to the first moving object they see after birth. Lorenz’s work led developmentalists to consider the ways in which human behavior might reflect inborn genetic patterns. Working with geese, he investigated the principle of imprinting, the process by which some nidifugous birds (i.e. birds that leave their nest early) bond instinctively with the first moving object that they see within the first hours of hatching. Although Lorenz did not discover the topic, he became widely known for his descriptions of imprinting as an instinctive bond.

In psychology and ethology, imprinting is any kind of phase-sensitive learning (learning occurring at a particular age or a particular life stage) that is rapid and apparently independent of the consequences of behavior. It was first used to describe situations in which an animal or person learns the characteristics of some stimulus, which is therefore said to be “imprinted” onto the subject. Imprinting is hypothesized to have a critical period.

Behavioral Genetics

The evolutionary perspective encompasses one of the fastest-growing areas within the field of lifespan development: behavioral genetics. Behavioral genetics is a field of scientific research that uses genetic methods to investigate the nature and origins of individual differences in behavior and studies the effects of heredity on behavior. Behavioral geneticists strive to understand how we might inherit certain behavioral traits and how the environment influences whether we actually displayed those traits. It also considers how genetic factors may influence psychological disorders such as schizophrenia, depression and substance abuse.[4][5][6]

Link to Learning

In Stanford professor and author of Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers, Robert Sapolsky’s Ted Talk (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ORthzIOEf30), Sapolsky describes how our history and biology influence our behavior. This tour of our individual and collective history provides an enlightening overview of behavioral genetics.

Criticisms of the Evolutionary Perspective

Try It

Comparing and Evaluating Lifespan Theories

Developmental theories provide a set of guiding principles and concepts that describe and explain human development. Some developmental theories focus on the formation of a particular quality, such as Piaget’s theory of cognitive development. Other developmental theories focus on growth that happens throughout the lifespan, such as Erikson’s theory of psychosocial development. It would be natural to wonder which of the perspectives provides the most accurate account of human development, but clearly, each perspective is based on its own premises and focuses on different aspects of development. Many lifespan developmentalists use an eclectic approach, drawing on several perspectives at the same time because the same developmental phenomenon can be looked at from a number of perspectives.

In the table below, we’ll review some of the major theories that you learned about in this module. Recall that three key issues considered in human development examine if development is continuous or discontinuous, if it is the same for everyone or distinct for individuals (one course of development or many), and if development is more influenced by nature or by nurture. The table below reviews how each of these major theories approaches each of these issues.

| Table 1. Major Theories in Human Development[10] | |||||

| Theory | Major ideas | Continuous or discontinuous development? | One course of development or many? | More influenced by nature or nurture? | Major Theorist(s) |

| Psychosexual theory | Behavior is motivated by inner forces, memories, and conflicts that are generally beyond people’s awareness and control. Emphasizes the unconscious, defense mechanisms, and influences of the id, ego, and superego. | Discontinuous; there are distinct stages of development | One course; stages are universal for everyone | Both; natural impulses combined with early childhood experiences impact development | Sigmund Freud |

| Psychosocial theory | A person negotiates biological and sociocultural influences as they move through eight stages, each characterized by a psychosocial crisis: trust vs. mistrust, autonomy vs. shame/doubt, initiative vs. guilt, industry vs. inferiority, identity vs. role confusion, intimacy vs. isolation, generativity vs. stagnation, ego integrity vs. despair. | Discontinuous; there are distinct stages of development | One course; stages are universal for everyone | Both; natural impulses combined with sociocultural experiences impact development | Erik Erikson |

| Classical conditioning | Learning by the association of a response with a stimulus; a person comes to respond in a particular way to a neutral stimulus that normally does not bring about that type of response. | Continuous; learning is ongoing without distinct stages | Many courses; learned behaviors vary by person | Mostly nurture; behavior is conditioned | Ivan Pavlov, John Watson |

| Operant conditioning | Learning that occurs when a voluntary response is strengthened or weakened by its association with positive or negative consequences. Rewards and punishments can strengthen or discourage behaviors. | Continuous; learning is ongoing without distinct stages | Many courses; learned behaviors vary by person | Mostly nurture; behavior is conditioned | B.F. Skinner |

| Social cognitive theory (social learning theory) | Learning occurs in a social context; considering the relationship between the environment and a person’s behavior. Learning can occur through observation. | Continuous; learning is gradual and ongoing without distinct stages | Many courses; learned behaviors vary by person | Mostly nurture; behavior is observed and learned | Albert Bandura |

| Piaget’s theory of cognitive development | A theory about how people come to gradually acquire, construct, and use knowledge and information. It describes cognitive development through four distinct stages: sensorimotor, preoperational, concrete, and formal. | Discontinuous; there are distinct stages of development | One course; stages are universal for everyone | Both; natural impulses combined with experiences that challenge the existing schemas | Jean Piaget |

| Information processing | A theory that seeks to identify the ways individuals take in, use, and store information (sometimes compared to a computer). It is based on the idea that humans process the information they receive, rather than merely respond to stimuli. | Continuous; cognitive development is gradual and ongoing without distinct stages | One course; the model applies to everyone | Both; natural cognitive development combined with experiences of processing information in new and different ways | Richard Atkinson, Richard Shiffrin |

| Humanistic theories | Theories that emphasizes an individual’s inherent drive towards self-actualization and contend that people have a natural capacity to make decisions about their lives and control their own behavior. Key terms and concepts include unconditional positive regard, striving for “the good life,” and the hierarchy of needs. | Continuous; development is ongoing without distinct stages and can be multidirectional depending on environmental circumstances | Mostly one course; Maslow’s hierarchy of needs is universally applied, but there is an individual course for self-actualization | Mostly nurture; development is influenced by environmental circumstances and social interactions | Carl Rogers, Abraham Maslow |

| Sociocultural theory | Vygotsky’s theory that emphasizes how cognitive development proceeds as a result of social interactions between members of a culture. Key terms and concepts include the zone of proximal development and scaffolding. | Both, but mostly continuous as an individual learns and progresses | Many courses; there are variations between individuals and cultures | Both; development is influenced by biological preparation and social experiences | Lev Vygotsky |

| Bioecological systems model | Urie Bronfenbrenner’s theory stressing the importance of studying a child in the context of multiple environments, or ecological systems. It is organized into five levels of external influence: microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, macrosystem, and chronosystem. | Both; the influence of each system can be continuous or discontinuous depending on the system in question | Many courses; the interaction of people and the environment varies | Both; a person’s biological potential and the environment interact to impact development | Urie Bronfenbrenner, Stephen Ceci |

| Evolutionary psychology theory | A theory that seeks to identify behavior that is a result of our genetic inheritance from our ancestors. | Continuous; current behaviors have been shaped over multiple generations based on successful survival and reproduction | Both; behavioral genetics show similarities across the species, but our unique family history also plays a role in development | Both; our genetic history and biological impulses interact with life experiences to produce individual development and development across the history and future of the species | Charles Darwin, David Buss, Konrad Lorenz, Robert Sapolsky |

GLOSSARY

behavioral genetics: one of the fastest-growing areas within the field of lifespan development and studies the effects of heredity on behavior

bioecological model: the perspective suggesting that multiple levels of the environment interact with biological potential to influence development

chronosystem: the environmental events and transitions that occur throughout a child’s life, including any socio-historical events

congruence: an instance or point of agreement or correspondence between the ideal self and the real self in Rogers’ humanistic personality theory

contextual perspective: a theory that considers the relationship between individuals and their physical, cognitive, and social worlds

ecological systems theory: Urie Bronfenbrenner’s theory stressing the importance of studying a child in the context of multiple environments, organized into five levels of external influence: microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, macrosystem, and chronosystem

exosystem: the larger contexts of the community, including the values, history, and economy

ethology: the study of behavior through a biological lens

evolutionary psychology: a field of study that seeks to identify behavior that is a result of our genetic inheritance from our ancestors

humanism: a psychological theory that emphasizes an individual’s inherent drive towards self-actualization and contends that people have a natural capacity to make decisions about their lives and control their own behavior

imprinting: in psychology and ethology, imprinting is any kind of phase-sensitive learning (learning occurring at a particular age or a particular life stage) that is rapid and apparently independent of the consequences of behavior

macrosystem: cultural elements such as global economic conditions, war, technological trends, values, philosophies, and a society’s responses to the global community which impact a community

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs: a motivational theory in psychology comprising a five-tier model of human needs, often depicted as hierarchical levels within a pyramid. Needs lower down in the hierarchy must be satisfied before individuals are motivated to attend to needs higher up

mesosystem: larger organizational structures such as school, the family, or religion

microsystem: immediate surrounds including those who have direct, significant contact with the person, such as parents or siblings

phenomenal field: our subjective reality, all that we are aware of, including objects and people as well as our behaviors, thoughts, images, and ideas

scaffolding: a process in which adults or capable peers model or demonstrate how to solve a problem, and then step back, offering support as needed

self-actualization: according to humanistic theory, the realizing of one’s full potential can include creative expression, a quest for spiritual enlightenment, the pursuit of knowledge, or the desire to contribute to society. For Maslow, it is a state of self-fulfillment in which people achieve their highest potential in their own unique way

sociocultural theory: Vygotsky’s theory that emphasizes how cognitive development proceeds as a result of social interactions between members of a culture

zone of proximal development (ZPD): the difference between what a learner can do without help, and what they can do with help

- David M. Buss The Evolution of Desire: Strategies of Human Mating BasicBooks, Jun 25, 2003 ↵

- Buss, A.H 2012 Pathways to individuality: evolution and development of personality traits. Washington, DC: American psychological Association ↵

- Easton, JM., Schipper, L., And Shackleford, T. 2007 morbid jealousy from an evolutionary psychological perspective. Evolution and human behavior, 28, 399 –402 ↵

- Origins of the Social Mind: Evolutionary Psychology and Child Development, Bruce J. Ellis, David F. Bjorklund pp 3-18 New York Guilford Press, Jan 1, 2005 ↵

- Rembis , M. 2009( re)defining disability in the “genetic age”: behavioral genetics, “new” eugenics and the future of impairment. Disability and society, 24, 585 - 597 ↵

- PLOMIN, R., DEFRIES, J. C. , KnOPIK, V. S., & NEIDERHISER, J. M. 2016. Top 10 replicated findings from behavioral genetics. Perspectives on psychological science, 11, 3–23. ↵

- Bjorklund, D. 2006 mother knows best, epigenetic inheritance, maternal effects, and the evolution of human intelligence. Developmental review, 26, 213 –242. ↵

- Baptista, T., Aldana, E., Angeles , F., And Beaulieu , S. 2008. Evolution theory: an overview of its applications in psychiatry. Psychopathology, 41, 17 –27. ↵

- Del Giudice, M. 2015. Self-regulation in an evolutionary perspective. In G. E. Gendolla, M. Tops, S. L. Koole, G. E. Gendolla, M. Tops, & S. L. Koole (Eds), Handbook of behavioral approaches to self-regulation. New York, New York: Springer science + business media ↵

- Berk, L. E. (1998). "Stances of Major Theories on Basic Issues in Human Development."Development through the lifespan. Boston: Allyn and Bacon. p. 26. ↵